Beyond Borders and Bargains: Japanese Supreme Court Tackles Value Shifting via Foreign Subsidiaries in the Obunsha Holdings Case

Date of Judgment: January 24, 2006

Case Name: Corporate Tax Reassessment Invalidation Lawsuit (平成16年(行ヒ)第128号)

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench

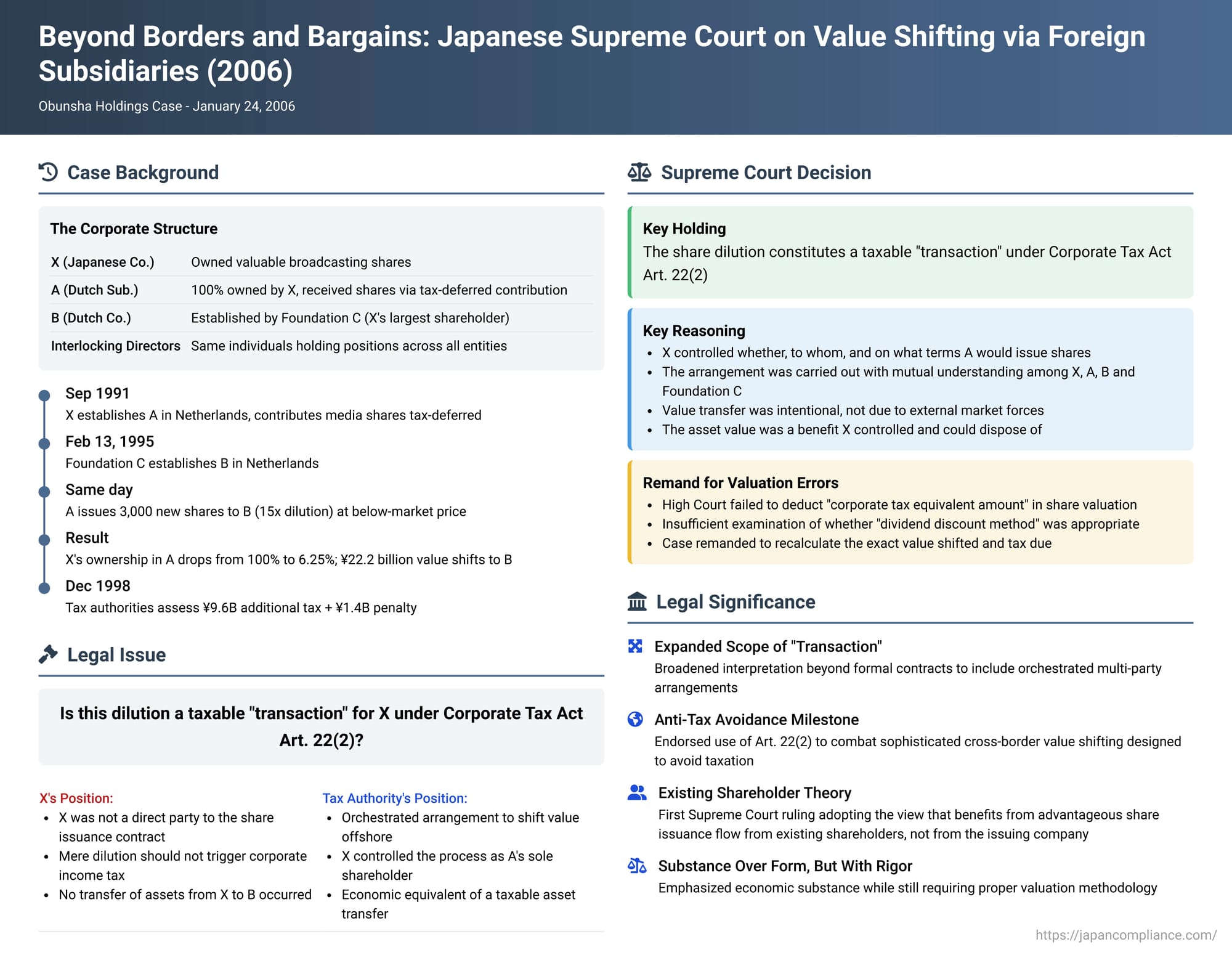

In a landmark decision dated January 24, 2006, the Supreme Court of Japan delivered a pivotal judgment on the interpretation of "transaction" under Article 22, paragraph 2 of the Corporate Tax Act. The case involved a sophisticated international corporate structure and an "advantageous share issuance" (a capital increase where new shares are issued at a price significantly below their fair value) by a foreign subsidiary, which resulted in a massive shift of asset value to an affiliated entity. The ruling has had profound implications for how Japan taxes perceived income from such value transfers, particularly in cross-border contexts designed to minimize taxation.

The Intricate Web: A Tax-Driven Corporate Maneuver

The appellant, a Japanese corporation we will call X (formerly Obunsha Holdings), held appreciated shares in two media companies, C-Broadcasting and D-Broadcasting ("the subject shares").

The key steps in the arrangement were as follows:

- Establishment of Dutch Subsidiary A: In September 1991, X established A (formerly Atlantic), a wholly-owned subsidiary in the Netherlands. X contributed the subject shares and cash to A, receiving 200 shares in A in return. Importantly, X utilized a provision in the then-existing Corporate Tax Act (former Article 51, paragraph 1) for "specified contributions in kind" to defer Japanese corporate income tax on the unrealized capital gains inherent in the subject shares. A was described as a paper company without its own significant operations or employees.

- Establishment of Dutch Subsidiary B: On February 13, 1995, Foundation C (formerly Century Cultural Foundation), which was X's largest shareholder holding 49.6% of its stock, established B (formerly Asuka Fund), a wholly-owned subsidiary also in the Netherlands.

- Interlocking Directorates: A notable feature was the presence of individuals from X's founding family who held concurrent directorial positions across X, A, B, and Foundation C. For instance, one individual, F, was a director and advisor to X, the chairman of Foundation C, a representative director of A, and a director of B. Another individual, G, was the representative director of X, a trustee of Foundation C, a representative director of A, and a director of B. This indicated a high degree of coordinated control.

- The Advantageous Share Issuance: On the same day B was established (February 13, 1995), A, at the direction of its then-sole shareholder X, undertook a significant capital increase by issuing 3,000 new shares directly to B. This represented a 15-fold increase in A's total issued shares. B paid approximately 3.03 million Dutch guilders (equivalent to about ¥176 million at the time) for these shares. This subscription price was substantially below the pre-existing fair value per share of A.

- Dilution and Value Shift: As a direct consequence of this third-party allotment to B, X's ownership stake in A plummeted from 100% to just 6.25%. Conversely, B became the dominant shareholder in A, holding 93.75% of its shares. This orchestrated dilution resulted in a massive transfer of the underlying asset value of A—initially represented entirely by X's 200 shares—to B, without X receiving any direct compensation for this diminution in its share value. The Tokyo High Court, in a later remand decision, quantified this shifted value at approximately ¥22.2 billion.

- Tax Environment: Critically, under the prevailing Japan-Netherlands tax treaty and Dutch domestic tax laws at the time, B was reportedly not subject to Dutch tax on the economic benefit it received from this advantageous share acquisition. Furthermore, because B was owned by Foundation C (a Japanese public interest foundation), the gain was also structured to avoid immediate taxation under Japan's anti-tax haven rules (Controlled Foreign Corporation or CFC rules), which might otherwise have attributed B's income back to a Japanese parent.

The Japanese tax authorities (Y tax office head) viewed this series of events as a scheme to transfer value out of X's taxable sphere. For X's fiscal year ending September 1995, Y issued a corrective tax assessment in December 1998, effectively treating the value shifted to B as taxable income for X, leading to an increased corporate tax liability of approximately ¥9.6 billion, plus an underpayment penalty of about ¥1.4 billion. Initially, the tax office based its assessment on Article 132, paragraph 1 of the Corporate Tax Act (a general anti-avoidance provision for family corporations), but during the first trial, it changed its primary argument to Article 22, paragraph 2.

The Tokyo District Court initially ruled in favor of X, finding that neither Article 22(2) nor Article 132 applied. However, the Tokyo High Court reversed this, upholding the tax office's position based on Article 22(2) and fully endorsing the tax office's valuation of the transferred asset value. X then appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Legal Crux: Is This Dilution a Taxable "Transaction" for X?

The central legal question before the Supreme Court was whether the substantial shift in asset value from X to B, facilitated by A's advantageous share issuance, could be considered a "transaction" that generated taxable income for X under Article 22, paragraph 2 of the Corporate Tax Act. This provision broadly defines taxable gross revenue (ekikin) to include income arising from the transfer of assets (whether for consideration or not) and "other transactions".

The taxpayer, X, argued that it was not a direct party to the share issuance contract between A and B, and that a mere dilution of its share value in A should not trigger corporate income tax under this provision. The tax authorities, however, contended that the entire arrangement was orchestrated by X to shift value to B without consideration, and this constituted a taxable event.

The Supreme Court's Affirmation and Remand

The Supreme Court, in its January 24, 2006 judgment, largely sided with the tax authorities on the application of Article 22(2) but remanded the case for a re-evaluation of the asset values involved.

Part 1: The "Transaction" – Affirming Taxability for X

The Court upheld the High Court's finding that the value shift was indeed taxable to X under Article 22(2). Its reasoning was as follows:

- X's Control: As the sole shareholder of A prior to the new share issuance, X was in a position to freely decide whether A would issue new shares, to whom these shares would be issued, and under what conditions (including price).

- Intent to Transfer Value: By causing A to issue a disproportionately large number of new shares (15 times the existing total) to B at a markedly advantageous price, X clearly intended to reduce its own shareholding percentage in A (from 100% to 6.25%) and thereby cause B to acquire a 93.75% stake. This action was specifically designed to transfer a substantial portion of A's underlying asset value—value previously represented by X's original 200 shares—to B without X receiving any consideration for this loss of value.

- Mutual Understanding and Orchestration: The new share issuance was not an isolated event but was carried out with the mutual understanding and common intention of the officers of X, A, B, and Foundation C, facilitated by the interlocking directorates. B was fully aware of these circumstances and knowingly received the transferred asset value.

- Asset Value as a Controllable Benefit: The asset value inherent in X's shares in A was a benefit that X clearly controlled and could dispose of. X, through its actions, chose to transfer this controllable benefit to B based on an agreement (explicit or implicit) with B.

- Not External Factors: Crucially, the Court found that this transfer of asset value was not the result of external market forces or other factors beyond X's control. Instead, it was the realization of a plan intended by X and understood and accepted by B.

- Conclusion on "Transaction": Based on these elements—control, intent, agreement, and the non-external nature of the cause—the Supreme Court concluded that this orchestrated shift of asset value constituted a "transaction" within the meaning of Article 22, paragraph 2 of the Corporate Tax Act, making the transferred value taxable income for X.

Part 2: The Valuation Errors – Remand for Reassessment

While agreeing on the taxability of the transaction, the Supreme Court found that the High Court had erred in its methods for valuing the unlisted shares that formed the basis of A's asset value (specifically, shares in D-Broadcasting, H-Television, and C-Broadcasting, which A held or held indirectly).

- The Court determined that, for the relevant period (February 1995), the High Court was incorrect in not deducting the "corporate tax equivalent amount" (法人税額等相当額 - hōjinzeigaku tō sōtōgaku) when valuing the shares of D-Broadcasting using the net asset value method. This adjustment accounts for latent corporate tax liabilities on unrealized gains within a company and is a standard feature of share valuation for inheritance and gift tax purposes under Japan's National Tax Agency's Property Valuation Basic Circulars (財産評価基本通達 - Zaisan Hyōka Kihon Tsūtatsu). The Supreme Court stated that this principle of deducting the corporate tax equivalent was generally applicable at the time, even for corporate tax valuation purposes, unless specific circumstances making it unreasonable were present.

- Regarding shares in H-Television and C-Broadcasting held by A (or its subsidiaries), the Supreme Court found that the High Court had failed to adequately examine whether the "dividend discount method" (配当還元方式 - haitō kangen hōshiki) should have been applied. This method is often considered appropriate for valuing shares held by minority shareholders who primarily expect dividends rather than exercising control, and X (via A) was a minority shareholder in these specific media companies. The High Court had not sufficiently investigated the shareholding ratios and other circumstances to justify dismissing this method outright in favor of a net asset value approach without the corporate tax equivalent deduction.

Due to these valuation errors, the Supreme Court quashed the High Court's decision and remanded the case for a recalculation of the transferred asset value, and consequently, X's tax liability.

Landmark Implications of the Obunsha Ruling

The Obunsha Holdings judgment is considered a watershed moment in Japanese tax law for several reasons:

- Broadened Scope of "Transaction" under Article 22(2): The ruling significantly expanded the interpretation of "transaction" beyond formal, bilateral contracts. It demonstrated that Article 22(2) could be applied to tax value shifts occurring in more complex, multi-party arrangements, even where the taxpayer deemed to have realized income (X) was not a direct contractual party to the specific act (the share issuance by A to B) that finalized the value transfer. This opened the path for Article 22(2) to be used by tax authorities as a more general anti-avoidance provision, rather than just a rule for straightforward asset sales or gifts.

- Countering Sophisticated Cross-Border Tax Avoidance: This was a pioneering Supreme Court decision that explicitly endorsed the use of Article 22(2) to tax unrealized capital gains that were effectively moved offshore to related parties in low-tax or no-tax jurisdictions. It showed that Article 22(2) could serve as a potent tool to address perceived gaps in then-existing specific anti-avoidance legislation, such as CFC rules or transfer pricing regulations, in the context of international tax planning.

- Relationship with General Anti-Avoidance Rules (Art. 132): The tax authorities had initially invoked Article 132 (the general anti-avoidance rule for closely held corporations) before shifting their primary reliance to Article 22(2). The Supreme Court's decision to affirm the tax based on Article 22(2) without making any pronouncement on Article 132's applicability has been interpreted by some scholars as aligning with the view that if Article 22(2) (as a more fundamental income calculation provision) can adequately address the situation and the tax outcome is similar, it should be preferred.

- Adoption of the "Existing Shareholder Theory": In the context of an advantageous share issuance, there's a theoretical question: does the economic benefit flow from the issuing company to the new subscriber, or from the existing shareholders (who suffer dilution) to the new subscriber? The Obunsha ruling was the first Supreme Court decision to clearly adopt the "existing shareholder theory" (既存株主説 - kizon kabunushi setsu), viewing the value as having been transferred from X (the existing shareholder) to B (the new subscriber). This has had significant implications for how Japanese tax law conceptualizes and potentially taxes such events, affecting not just the diluted shareholder but also potentially the recipient of the benefit.

Lingering Questions and Subsequent Developments

Despite its significance, the Obunsha ruling also left some questions open, particularly regarding the precise conditions required to apply Article 22(2) in situations lacking a direct private law "transaction" between the party deemed to have transferred value and the party deemed to have received it. For instance, the Supreme Court in Obunsha emphasized X's control and the "mutual understanding" or "agreement" for the value transfer. Subsequent lower court decisions, such as a notable Tokyo High Court case involving a major trading company's Thai subsidiary, have continued to grapple with whether such a "meeting of minds" is a strict prerequisite for applying Article 22(2) in all advantageous issuance scenarios, or if the objective economic effect of value transfer can suffice under certain conditions. This indicates that the judicial interpretation in this complex area continues to evolve.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's judgment in the Obunsha Holdings case stands as a critical precedent in Japanese corporate tax law. It affirmed a broad and economically substantive interpretation of "transaction" under Article 22, paragraph 2, enabling tax authorities to address sophisticated, often cross-border, schemes designed to shift value and defer or avoid taxation on unrealized gains. While upholding the taxability of the value transfer orchestrated by X, the Court also underscored the necessity of applying correct and justifiable valuation methodologies, leading to the remand of the case. This dual focus—aggressively interpreting income inclusion provisions while insisting on rigorous valuation—highlights Japan's ongoing efforts to balance anti-avoidance principles with the rule of law in the complex world of corporate taxation.