Beyond a Flutter: Japanese Supreme Court Rules on Tax Treatment of Systematic Horse Race Winnings

Date of Judgment: December 15, 2017

Case Name: Income Tax Reassessment Invalidation Lawsuit (平成28年(行ヒ)第303号)

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench

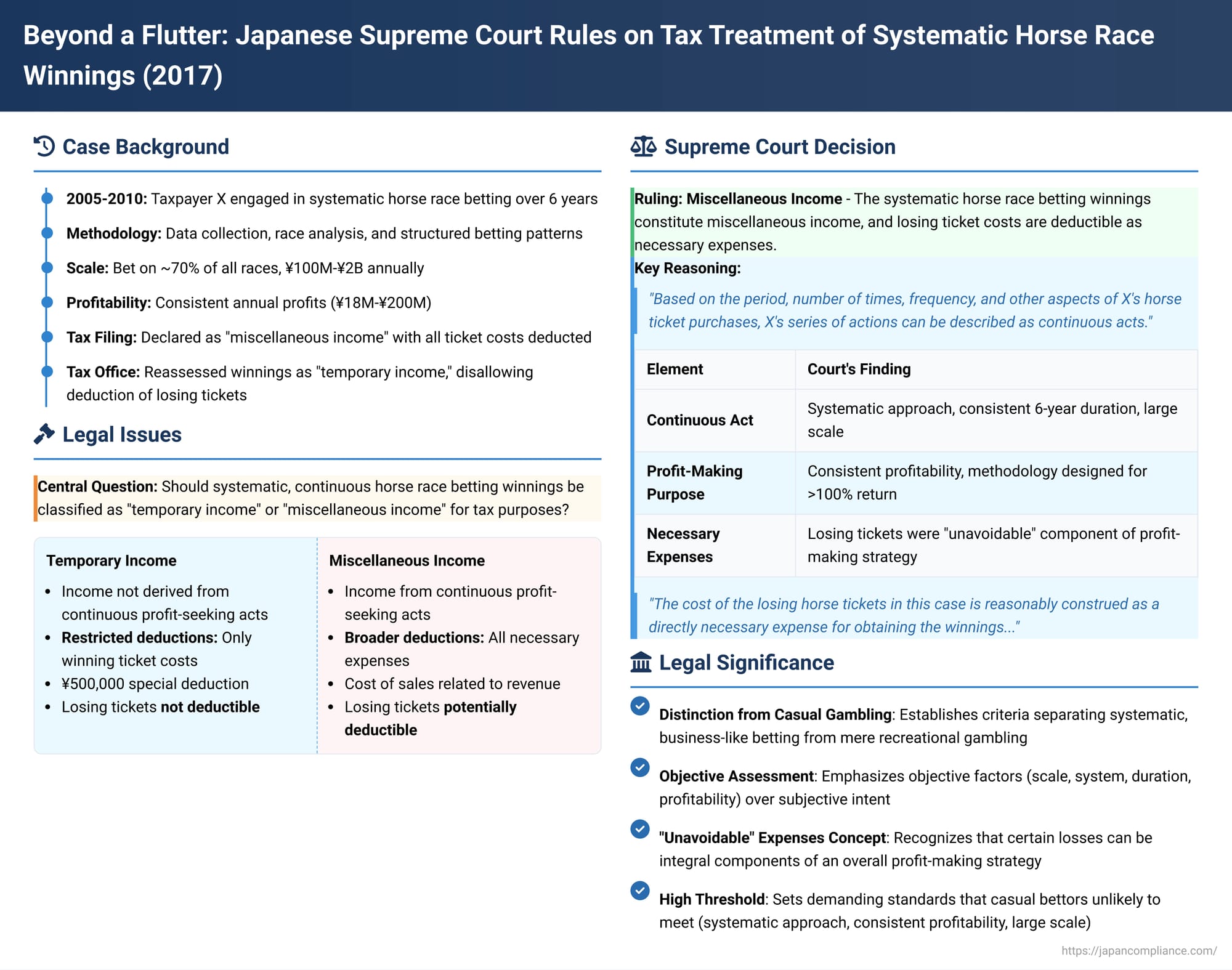

In a significant decision dated December 15, 2017, the Supreme Court of Japan provided crucial clarification on the tax treatment of substantial winnings derived from systematic and continuous horse race betting. The case revolved around whether such income should be classified as "temporary income" (一時所得 - ichiji shotoku), where the deduction of losing bets is highly restricted, or "miscellaneous income" (雑所得 - zatsu shotoku), which allows for the deduction of necessary expenses, including the cost of losing wagers, under specific conditions.

This ruling has important implications for understanding how Japanese tax law distinguishes between sporadic, chance-based gains and income generated from more structured, profit-oriented activities, even in areas traditionally associated with gambling.

Background of the Dispute

The case involved an individual, whom we will refer to as X, who engaged in extensive horse race betting over a six-year period, from 2005 to 2010. X utilized an online service to purchase a large volume of betting tickets.

X’s betting was not random. It was based on a sophisticated, self-developed system. This system involved:

- Continuous Data Collection: X gathered and accumulated information on all registered racehorses and jockeys, racecourse characteristics, and trends.

- In-depth Analysis: X personally analyzed this data, evaluating factors such as a horse's ability, jockey's skill, course suitability, gate position, track conditions, race dynamics, and the horse's current condition to predict race outcomes.

- Structured Betting Patterns: Based on this analysis, X established multiple betting patterns. These patterns varied the amount, type, and proportion of bets placed, determined by the assessed probability of a win and the expected payout rates.

- Scale and Frequency: X aimed to bet on nearly all races throughout the year to mitigate the impact of chance. This resulted in bets totaling several hundred million to over two billion yen annually. For instance, in 2009, a year for which records from the horse racing association were available, X bet on 2,445 out of 3,453 races, approximately 70.8% of all races held.

- Profit-Driven Strategy: The overarching strategy was to achieve an overall profit when looking at the annual balance of winnings against the total cost of all tickets (both winning and losing).

This methodical approach proved consistently profitable. For each of the six years in question, X's winnings exceeded the total cost of tickets purchased. The annual profits ranged from approximately ¥18 million in 2005 to around ¥200 million in 2009.

When filing income tax returns for these years, X declared the net profits from horse racing as "miscellaneous income." Accordingly, X deducted the cost of all purchased betting tickets, including losing ones, as necessary expenses.

However, the head of the relevant tax office disagreed. The tax office reclassified X's winnings as "temporary income." Under this classification, the cost of losing tickets could not be deducted from the winnings. This reassessment resulted in significantly higher tax liabilities for X, along with penalties for underpayment and, for some years, failure to file correctly. X challenged these reassessments, seeking their cancellation.

The initial court (Tokyo District Court) ruled in favor of the tax office. However, the Tokyo High Court overturned this decision, siding with X. The government, representing the tax office, then appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Legal Framework: Temporary Income vs. Miscellaneous Income

Japanese income tax law categorizes income into ten different types. After specific categories such as interest, dividend, real estate, business, employment, retirement, timber, and capital gains income are considered, any remaining income generally falls into either "temporary income" or "miscellaneous income."

- Temporary Income (一時所得 - ichiji shotoku): As defined in Article 34(1) of the Income Tax Act, this generally refers to income that is not derived from continuous acts for profit-making purposes, is not compensation for labor or services, and is not derived from the transfer of assets. Examples often include one-off lottery winnings, prizes, or insurance payouts. A key feature of temporary income is that only the direct cost incurred to obtain that specific winning (e.g., the cost of the single winning lottery ticket) can be deducted, along with a special deduction up to ¥500,000. The cost of losing efforts in similar activities is generally not deductible.

- Miscellaneous Income (雑所得 - zatsu shotoku): According to Article 35(1) of the Income Tax Act, this is income that does not fall into any of the other nine categories. Crucially, income derived from "continuous acts for profit-making purposes" that isn't classified as business income or another specific income type typically falls under miscellaneous income. For miscellaneous income, Article 37(1) allows for the deduction of "cost of sales related to the gross revenue of miscellaneous income and other expenses directly incurred to obtain said gross revenue" – essentially, necessary expenses.

The distinction was critical in X's case. If the winnings were temporary income, the vast sums spent on losing tickets would not be deductible, leading to a tax liability potentially exceeding the actual net profit. If classified as miscellaneous income, the cost of losing tickets could potentially be deducted as necessary expenses, provided they met the criteria.

The Supreme Court's Judgment

The Supreme Court upheld the High Court's decision in favor of X, ruling that the income was indeed "miscellaneous income" and that the cost of losing tickets was deductible as necessary expenses.

The Court's reasoning focused on whether X's betting activities constituted "income from continuous acts for profit-making purposes." It referenced a prior Supreme Court judgment (a criminal case from March 10, 2015, concerning automated betting software) which established that this determination should be made by comprehensively considering factors such as the period, number of times, frequency, and other aspects of the act, as well as the scale, duration, and other circumstances of profit generation.

Applying this framework, the Court analyzed X's activities:

1. "Continuous Act" (継続的行為 - keizokuteki kōi)

The Court found X's betting to be a "continuous act" based on:

- Systematic Approach: X followed defined purchase patterns based on predicted win probabilities and payout rates.

- Goal of Broad Participation: X aimed to bet on almost all races throughout the year to reduce the impact of chance and actively devised ways to ensure an annual profit.

- Duration and Scale: X engaged in this activity consistently for six years, purchasing a large number of tickets, amounting to hundreds of millions to billions of yen annually.

The Court stated: "Given the period, number of times, frequency, and other aspects of X's horse ticket purchases, X's series of actions can be described as continuous acts."

2. "Profit-Making Purpose" (営利を目的とする - eiri o mokuteki to suru)

The Court then considered whether these continuous acts were undertaken for a profit-making purpose. It concluded they were, based on:

- Consistent Profitability: X achieved a net profit (total winnings minus total betting costs) for all six years, with amounts ranging from approximately ¥18 million to ¥200 million.

- Methodology Aimed at Profit: The Court emphasized that X's betting methods, combined with the scale and duration of the profits, indicated that X had been selecting and purchasing tickets in a manner designed to ensure that the overall return rate would exceed 100%.

- Objective Assessment: The Court determined that X's series of actions were, when viewed objectively, for profit-making purposes. This implies that a mere subjective hope for profit is insufficient; the activity itself must have characteristics that objectively suggest a profit motive and a reasonable expectation of profit through the methods employed. The focus was on the systematic nature of the purchasing behavior designed to yield profit, not just the fortunate outcome of having a high return rate.

The Court concluded: "Based on the above, it is reasonable to construe that the income in question constitutes miscellaneous income as defined in Article 35, paragraph 1 of the Income Tax Act, as income arising from continuous acts for profit-making purposes."

Deductibility of Losing Bets as Necessary Expenses

Having classified the income as miscellaneous, the Supreme Court then addressed the deductibility of the cost of losing tickets. Article 37, paragraph 1 of the Income Tax Act allows for the deduction of costs directly incurred to obtain the gross revenue of miscellaneous income.

The Court reasoned that:

- X engaged in continuous betting, purchasing numerous tickets frequently over a long period, with the specific aim of mitigating the element of chance and securing an overall profit annually.

- Within this systematic approach, the purchase of losing tickets was an "unavoidable" (不可避 - fukahi) component of the overall activity designed to generate profit. The entire series of purchases, including those that resulted in losses, was integral to the profit-making endeavor.

Therefore, the Court held: "The cost of the losing horse tickets in this case is reasonably construed as a directly necessary expense for obtaining the winnings from the winning horse tickets, which constitute miscellaneous income, and thus falls under necessary expenses as stipulated in Article 37, paragraph 1 of the said Act."

This reasoning differentiates X's situation from typical, casual gambling. For a casual bettor, a losing ticket is simply a loss. For X, however, the losing tickets were part of a broader, calculated strategy where the volume and spread of bets (some inevitably losing) were statistically necessary to achieve the profitable outcomes on winning tickets and an overall annual profit. The profit was not sought from individual bets in isolation, but from the "series of horse ticket purchases" as a whole.

Significance of the Ruling

This Supreme Court decision is noteworthy for several reasons:

- Clarification for Non-Automated Systematic Betting: A previous landmark Supreme Court case (March 10, 2015) had recognized horse race winnings from systematic, software-aided betting as miscellaneous income. This 2017 ruling confirms that the same principle can apply even when the systematic approach does not involve automated purchasing software but is instead based on an individual's continuous, large-scale, and methodical efforts to analyze data and manage bets for profit.

- Emphasis on Objective Profit Motive and Methodology: The ruling underscores that the determination of a "profit-making purpose" involves an objective assessment of the activity's nature. It’s not just about hoping to win, but about implementing a system or method that could reasonably be expected to generate a consistent profit over time. The focus is on the sustained, rational effort to achieve profitability rather than reliance on mere chance.

- "Unavoidable" Expenses in a Series of Acts: The Court’s acceptance of losing bets as "unavoidable" and therefore deductible necessary expenses, in the context of a continuous and integrated profit-seeking activity, is a key takeaway. It recognizes that in certain large-scale, systematic operations, some expenditures that might appear as losses in isolation are, in fact, integral and necessary costs of generating the overall income.

- Distinction from Hobby or Sporadic Gambling: The case draws a clearer line, albeit based on a high threshold of activity and profitability, between casual gambling (where winnings are typically temporary income and losses non-deductible against those winnings) and a more structured, continuous pursuit of profit that can be treated as generating miscellaneous income. The sheer scale, frequency, systematic approach, and consistent profitability demonstrated by X were crucial factors.

This judgment does not mean all gambling winnings will now be treated as miscellaneous income. The specific facts of X's extensive, systematic, and consistently profitable activities were paramount. However, it does provide a precedent that when an activity, even one involving elements of chance, is conducted in a manner akin to a business operation – characterized by continuity, scale, a discernible methodology aimed at profit, and actual sustained profitability – the resulting income may be classified as miscellaneous income, allowing for a broader deduction of related expenses. This requires a comprehensive evaluation of the taxpayer's specific conduct and results.

Tax authorities and taxpayers alike must consider the objective nature, continuity, scale, and demonstrable profit-oriented methodology of such activities when determining the appropriate income classification and the scope of deductible expenses.