Betting Facilities and Neighborhood Peace: Who Can Sue Over an Off-Track Betting Permit in Japan?

Judgment Date: October 15, 2009, Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench

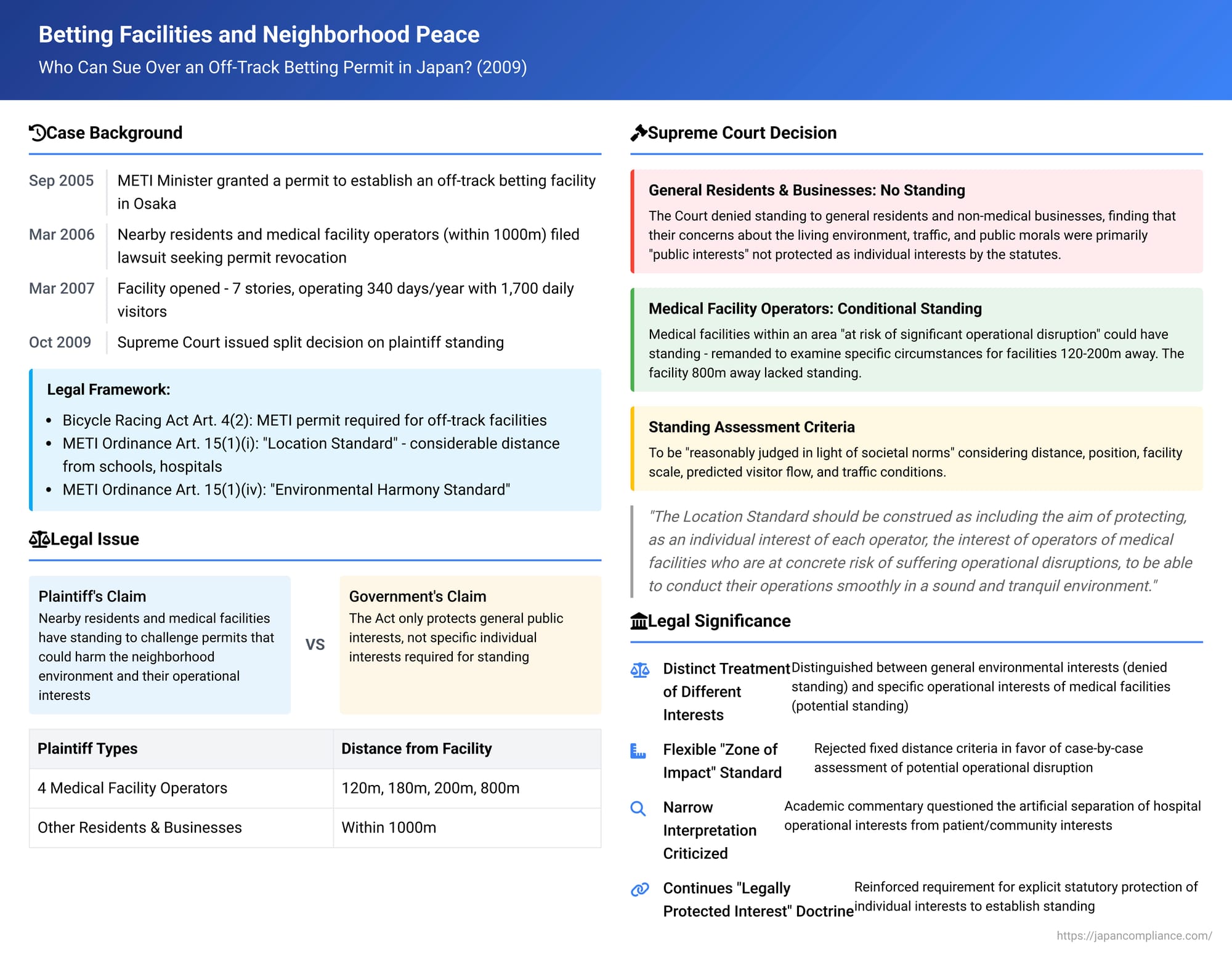

The establishment of off-track betting facilities for public sports like keirin (bicycle racing) can be a contentious issue, often pitting economic interests and local government revenues against the concerns of nearby residents and businesses about potential negative impacts on their living environment and public order. A 2009 Supreme Court decision addressed the crucial question of who has the legal standing—the right to sue—to challenge a permit granted for such a facility. This case provides important insight into how Japanese courts determine which third parties have a "legally protected interest" sufficient to bring an administrative lawsuit.

The Legal Framework: Regulating Off-Track Betting Facilities

In Japan, bicycle racing (競輪 - keirin) is one of several public sports where betting is legally permitted, typically run by local governments. To expand access and revenue, these local governments can establish, or authorize private entities to establish, off-track betting facilities (場外車券発売施設 - jōgai shaken hatsubai shisetsu), often called "satellites," where bets can be placed and races viewed.

The establishment of these facilities is regulated by the Bicycle Racing Act (自転車競技法 - Jitensha Kyōgi Hō). Article 4, Paragraph 2 of this Act (as it stood before a 2007 amendment) stipulated that the Minister of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI) could permit the establishment of an off-track facility only if its location, structure, and equipment met standards set by METI ordinance.

The implementing METI Ordinance (Bicycle Racing Act Enforcement Rules, pre-2006 amendment) set forth these standards in Article 15, Paragraph 1. Key among them were:

- Location Standard (位置基準 - ichi kijun): The facility must be a "considerable distance" from schools and other educational facilities, as well as hospitals and other medical facilities (collectively "medical facilities, etc." - 医療施設等 - iryō shisetsu tō), and must not pose a risk of significantly impairing educational or public health environments (Item 1).

- Environmental Harmony Standard (周辺環境調和基準 - shūhen kankyō chōwa kijun): The facility's scale, structure, equipment, and layout must be in harmony with the surrounding environment (Item 4).

Furthermore, Article 14, Paragraph 2 of the Rules required that an application for an off-track facility permit must include a vicinity map showing the location and names of medical facilities, etc., within 1000 meters of the proposed site, along with diagrams of traffic conditions.

The Osaka Betting Facility Dispute: Facts of the Case

The case concerned a permit granted by the Minister of Economy, Trade and Industry on September 26, 2005, to Company A to establish an off-track betting facility (referred to as "the Facility") in Osaka. The Facility was a seven-story building (plus one basement level) intended to be leased to Kishiwada City (a keirin race operator) for operations. It was projected to operate 340 days a year with an estimated 1,700 visitors per day and opened in March 2007.

A group of plaintiffs, X et al., comprising nearby residents and business operators, filed an administrative lawsuit in March 2006 seeking the revocation of the METI permit. Among the plaintiffs were four physicians operating hospitals or clinics located approximately 120m, 180m, 200m, and 800m from the Facility site. Other plaintiffs resided or operated businesses within 1000 meters of the Facility. They argued that the permit was illegal.

The primary legal battleground, before even reaching the merits of the permit's legality, was whether X et al. had the necessary "legal interest" (法律上の利益 - hōritsujō no rieki) to bring the lawsuit, as required by Article 9 of the Administrative Case Litigation Act (ACLA).

- The Osaka District Court (First Instance) denied standing to all plaintiffs. It reasoned that the Bicycle Racing Act and its implementing rules did not intend to protect the living environment interests of the plaintiffs as specific individual interests, but rather aimed at protecting general public interests.

- The Osaka High Court (Second Instance) reversed this decision. It found that the Act and rules did intend to protect the concrete interest of nearby residents not to suffer significant harm to their health or living environment from such facilities, and thus granted standing to all plaintiffs. The Minister (represented by the State) appealed this ruling.

The Supreme Court's Decision (October 15, 2009): Differentiating Among Nearby Parties

The Supreme Court, First Petty Bench, issued a nuanced judgment, partially overturning the High Court's broad recognition of standing. It applied the general test for standing established in cases like the 2005 Odakyu Line judgment (see Hyakusen II, No. 159), which involves assessing whether the relevant administrative laws aim to protect not just general public interests but also specific individual interests.

I. General Nature of Interests Related to Living Environment

The Court first observed that the potential harm from an off-track betting facility generally involves the "deterioration of the living environment in a broad sense, including traffic, public morals, and education." It stated that such facilities are "unlikely to be envisioned as immediately threatening the life, physical safety, or health of surrounding residents, or causing significant damage to their property." The Court characterized these "interests related to the living environment" as "fundamentally belonging to the public interest." Therefore, "it is difficult to construe the Act as intending to protect the interests of surrounding residents... as individual interests as well, unless there is a clear provision in the laws and regulations that serves as a clue."

II. Standing Denied for General Surrounding Residents

Based on this premise, the Court analyzed the "Location Standard" (METI Ordinance Art. 15(1)(i)), which requires facilities to be a considerable distance from medical facilities, etc., and not pose a risk of significant impairment to educational or public health environments.

- The Court found that "what the Act and Rules primarily intend to protect through the Location Standard... is the interest of an unspecified number of persons [such as promoting the sound upbringing of youth and public health]".

- This interest, by its nature, "belongs to the general public interest and is insufficient to provide a basis for plaintiff standing."

- "Therefore, persons who merely reside or operate businesses (excluding businesses related to medical facilities, etc.) in the vicinity of an off-track facility, or users of medical facilities, etc., do not have plaintiff standing based on the Location Standard."

III. Standing Potentially Affirmed for Operators of Medical Facilities, etc.

However, the Court carved out a potential exception for the operators of nearby medical facilities, etc.:

- ① The "Location Standard," while primarily serving the general public interest, "should also be construed as including the aim of protecting, as an individual interest of each operator, the interest of operators of medical facilities, etc., who are at concrete risk of suffering operational disruptions, to be able to conduct their operations smoothly in a sound and tranquil environment."

- Therefore, "a person who operates a medical facility, etc., in an area recognized, due to its location, as being at risk of suffering significant operational disruption accompanying the establishment and operation of the said off-track facility, has plaintiff standing based on the Location Standard."

- Whether an operator has such standing is to be "reasonably judged in light of societal norms, primarily based on the distance and positional relationship between the off-track facility and the medical facility, etc., taking into account the scale of the off-track facility, the flow and congregation of visitors reasonably predicted from the surrounding traffic and geographical conditions, etc."

- ② Applying this to the specific plaintiffs:

- The physician operating a medical facility approximately 800m away was found not to have standing, as their facility was not deemed to be in an area at risk of significant operational disruption.

- For the three physicians whose facilities were located approximately 120m to 200m away, the Court found it "difficult to accurately determine whether they have the aforementioned plaintiff standing without considering the aforementioned factors." It therefore quashed the High Court's uniform granting of standing and remanded this part of the case to the first instance court (Osaka District Court) for a more detailed examination of these specific circumstances.

IV. Role of the "Environmental Harmony Standard"

The Court also considered the "Environmental Harmony Standard" (METI Ordinance Art. 15(1)(iv)), which requires the facility's scale, structure, and layout to be in harmony with the surrounding environment.

- It held that even if this standard is interpreted as "including the aim of seeking harmony with the residential environment around the off-track facility, regulations from such a viewpoint are fundamentally regulations from the perspective of protecting the general public interest, such as preventing the mixed presence of buildings with different uses and promoting the orderly development of the urban environment."

- It is "difficult to read from this an aim to protect the concrete interests of those residing, etc., in the vicinity of the off-track facility as individual interests of each person."

- Therefore, this standard could not form the basis for standing for the surrounding residents or general business operators.

Significance and Analysis

This 2009 Supreme Court decision is a key ruling on third-party standing in the context of permits for facilities that may impact the local environment and public order.

Adherence to the "Legally Protected Interest" Test

The judgment reaffirms the Supreme Court's adherence to the "legally protected interest" theory for plaintiff standing, as refined by the 2004 ACLA amendment (Article 9, Paragraph 2) and articulated in the 2005 Odakyu Line decision. The core inquiry remains whether the specific provisions of the empowering statute (and related regulations) can be interpreted as intending to protect not just broad public interests but also the concrete, individual interests of the plaintiffs.

Distinction Between General Environmental Interests and Specific Operational Interests

A crucial aspect of this decision is the distinction it draws between different types of interests:

- General Living Environment: The Court viewed harms related to the broad "living environment" (traffic, public morals, general educational atmosphere) as primarily matters of public interest. Unless a statute clearly earmarks protection for individuals regarding these aspects, standing is unlikely.

- Specific Operational Interests of Medical/Educational Facilities: In contrast, the Court found that the "Location Standard" (requiring distance from schools, hospitals, etc.) did intend to protect the individual interest of the operators of these specific types of facilities to conduct their professional duties in a suitable (sound and tranquil) environment, free from significant operational disruption. This protection, however, was not extended to the general users of these facilities, nor to general residents or other businesses in the vicinity based solely on this standard.

The "Zone of Impact" for Facility Operators

For the operators of medical or educational facilities, the Court did not set a fixed distance (like the 1000m mentioned for submitting vicinity maps in the permit application) to determine standing. Instead, it mandated a case-by-case assessment based on whether the facility is located in an area "recognized, due to its location, as being at risk of suffering significant operational disruption." This involves considering factors like the scale of the betting facility, predicted visitor flows, traffic patterns, and the distance and positional relationship between the betting facility and the medical/educational facility, all judged "reasonably in light of societal norms." This flexible but demanding standard places a significant burden of proof on such plaintiffs.

Criticism of the Narrow Interpretation

Legal commentators have generally been critical of the restrictive approach to standing adopted in this case, particularly regarding general residents.

- The argument is that the purpose of restricting off-track betting facilities near residential areas and specific sensitive facilities inherently aims to protect the well-being of the individuals who live, work, or receive services in those areas.

- To separate the protection of a hospital's "operational interest" from the health and environmental interests of the patients it serves, or the residents living immediately adjacent to it, is seen by some as an artificial distinction.

- The reliance on interpreting the ministerial ordinance (the Rules) as the primary source for identifying protected interests, rather than deriving broader protective principles from the Act itself, has also been questioned.

Broader Implications for Environmental and Public Order Litigation

This case serves as an important precedent for other types of facilities that may be perceived as LULUs (Locally Unwanted Land Uses). It indicates that:

- The Supreme Court will closely scrutinize the specific wording and discernible purposes of the relevant regulatory statutes and ordinances to determine if individual interests are protected.

- General claims of harm to the "living environment" or "public morals" by ordinary residents may face a high hurdle unless a more specific, individualized legal interest, recognized by statute, can be demonstrated.

- Standing might be more readily acknowledged for entities (like the operators of schools or hospitals in this instance) whose operational functions are specifically contemplated as needing protection by the regulatory scheme.

The PDF commentary notes that this decision, by narrowly construing the scope of individually protected interests, particularly for general residents, contrasts with the somewhat broader approach seen in the Odakyu Line case concerning direct and significant impacts on health and living environment from railway noise and vibration. This suggests that the type of facility, the nature of the alleged harm, and the precise wording of the regulatory framework all play crucial roles in the Supreme Court's standing analysis.

Conclusion

The 2009 Supreme Court decision on the Osaka off-track betting facility permit provides a significant, albeit restrictive, interpretation of plaintiff standing for third parties challenging such establishments. While it opened a narrow path for operators of nearby medical or educational facilities to claim standing if they can demonstrate a risk of significant operational disruption, it largely denied standing to general residents and other businesses based on concerns about the deterioration of the broader living environment, public morals, or traffic conditions.

The judgment underscores the Supreme Court's continued reliance on the "legally protected interest" doctrine, requiring a clear link between the plaintiff's asserted harm and a protective intent discernible in the specific laws and regulations governing the challenged administrative action. It highlights the challenges citizens face in seeking judicial review of permits for facilities perceived as undesirable, unless they can frame their injury in terms of a specific, individually protected legal interest rather than a more general concern for public welfare or environmental quality.