Beneficial Ownership Transparency in Japan: Current Debates and Future Directions

TL;DR: Japan lags global peers on beneficial-ownership (BO) transparency, relying on a semi-public corporate registry and securities filings. G7 and FATF pressure has spawned proposals for an open BO register, lower thresholds, and harsher sanctions. Businesses should prepare for stricter disclosure and KYC obligations in the next two years.

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- The Current Landscape and the Transparency Gap

- Drivers for Enhancing Beneficial Ownership Transparency

- International Approaches: Potential Models for Japan?

- Potential Future Directions for Japan

- Challenges and Considerations

- Conclusion

Introduction

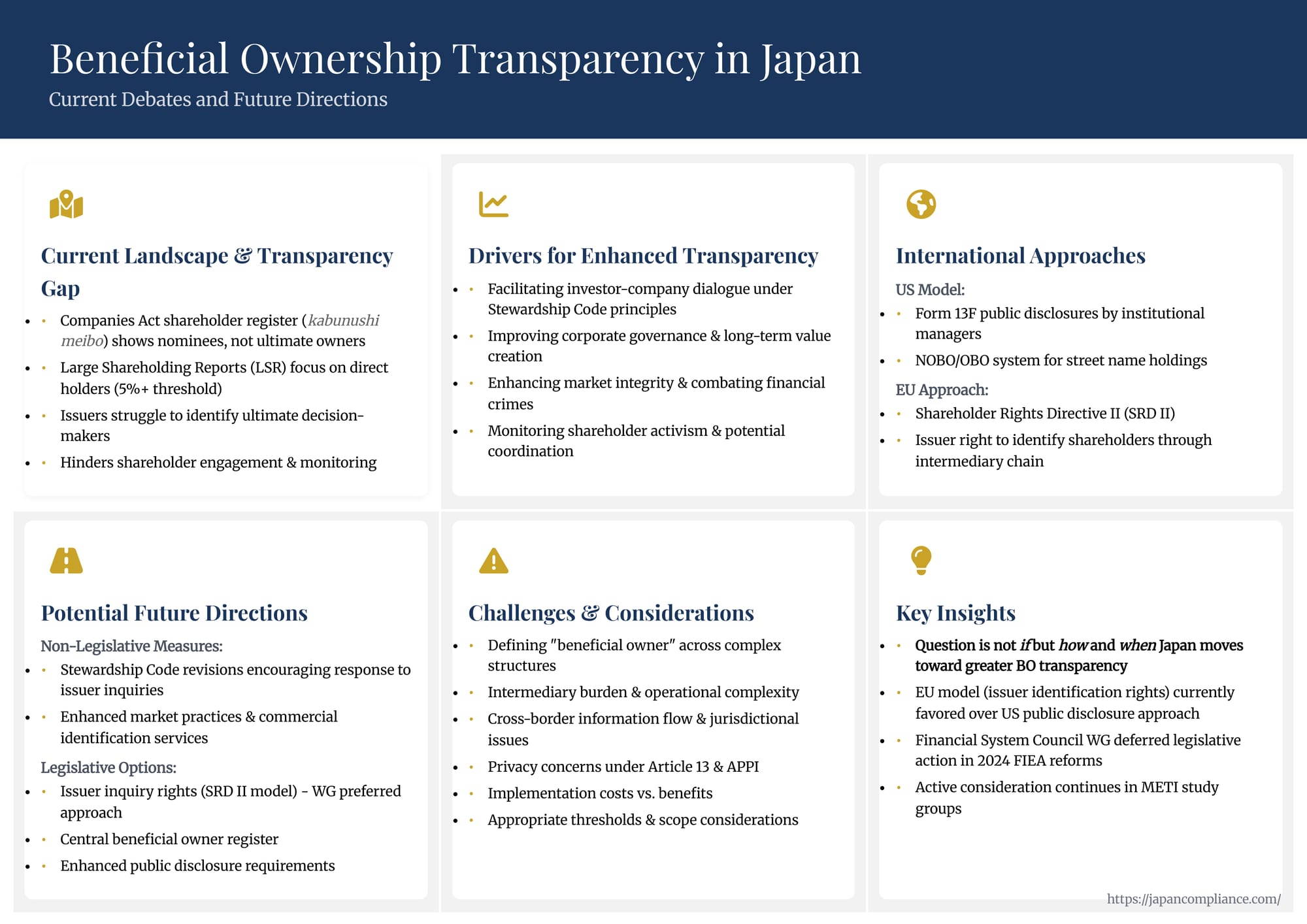

In today's complex global financial markets, understanding who ultimately owns and controls corporate shares is becoming increasingly vital. Knowing the true "beneficial owners"—the individuals who ultimately reap the economic benefits or exert control, often hidden behind layers of nominees and intermediaries—is fundamental for effective corporate governance, market integrity, and informed investor engagement. While Japan has established systems for disclosing significant shareholdings, identifying these ultimate beneficial owners often remains a challenge.

The issue of Beneficial Ownership (BO) transparency was a significant topic during the deliberations leading up to Japan's 2024 amendments to the Financial Instruments and Exchange Act (FIEA). However, unlike the reforms to Takeover Bids and Large Shareholding Reporting (LSR), specific legislative measures to mandate comprehensive BO disclosure were ultimately deferred, marked instead as a critical area for future consideration.

This article explores the current state of beneficial ownership transparency in Japan, examining why the existing framework is often considered insufficient. It delves into the key drivers pushing for reform, compares potential international models Japan might draw upon (notably the US and EU approaches), discusses the potential future directions—including non-legislative and legislative pathways—and outlines the significant challenges involved in implementing a more robust BO transparency regime.

1. The Current Landscape and the Transparency Gap

Japan currently relies on two main pillars for shareholder information, neither of which consistently reveals the ultimate beneficial owner:

- The Companies Act Shareholder Register (Kabunushi Meibo): This is the official register maintained by the company (or its transfer agent). Under Japanese company law, rights (like voting and dividends) are generally exercised based on this register. However, particularly for listed companies with significant foreign or institutional investment, the registered shareholder is often a nominee, custodian bank (like The Master Trust Bank of Japan or Custody Bank of Japan), or other intermediary, rather than the end investor making the voting or investment decisions.

- The FIEA Large Shareholding Reporting (LSR) System: This system requires holders exceeding a 5% threshold to file public reports. While the recent 2024 FIEA reforms refined aspects of the LSR (clarifying "joint holders" and expanding derivative disclosures), its primary focus remains on the legal or direct holder (or explicitly defined joint holders) who crosses the threshold. It does not systematically require tracing ownership through complex chains (e.g., multiple layers of funds or offshore entities) to identify the ultimate human beneficiary or controller, especially if no single entity in the chain directly holds over 5%.

The Transparency Gap:

The result is a potential "transparency gap." Issuers often struggle to identify the ultimate investors who hold significant economic stakes or voting power in their company, particularly when shares are held through omnibus accounts at custodian banks or complex international holding structures. While commercial shareholder identification services exist and are used by many companies, they rely on voluntary disclosure by intermediaries or analytical inference, lacking the force of legal obligation.

Consequences of the Gap:

This lack of clarity can hinder:

- Effective Shareholder Engagement: Companies find it difficult to directly engage in dialogue with the ultimate decision-makers regarding governance, strategy, or sustainability issues.

- Monitoring and Compliance: Regulators and other market participants may find it challenging to fully assess potential coordination among investors (e.g., "wolf packs" acting in concert below individual reporting thresholds) or monitor compliance with foreign ownership restrictions.

- Market Integrity: Obscured ownership can potentially facilitate market abuse or be exploited for illicit purposes like money laundering, although this is often addressed more directly through AML regulations.

2. Drivers for Enhancing Beneficial Ownership Transparency

The push for greater BO transparency in Japan stems from several interconnected factors:

- Facilitating Investor-Company Dialogue: This was identified as the primary driver in the Financial System Council Working Group discussions leading to the 2024 FIEA reforms. As Japan emphasizes the importance of the Stewardship Code and constructive engagement, companies argue they need to know who their ultimate investors are to have meaningful conversations about long-term value creation.

- Improving Corporate Governance: Understanding the true ownership structure can help companies tailor their governance practices, enhance board accountability to the ultimate capital providers, and inform strategies related to shareholder activism or potential takeovers.

- Enhancing Market Integrity and AML/CFT: While perhaps a secondary driver in the corporate governance context, aligning with global standards for BO transparency (e.g., Financial Action Task Force - FATF recommendations) is crucial for combating money laundering, terrorist financing, and other financial crimes. Clearer ownership trails can deter illicit activities.

- Understanding Activism: Greater transparency allows companies and the market to better identify activist investors, understand their strategies, and assess potential coordination among different funds or individuals.

3. International Approaches: Potential Models for Japan?

As Japan considers its path forward, it looks to international precedents. The Working Group specifically compared the US and EU models:

3.1. The US Approach

- Form 13F: Requires large institutional investment managers (exercising investment discretion over $100 million in certain securities) to publicly disclose their holdings quarterly via the SEC's EDGAR system.

- Limitations: Focuses on the manager, not necessarily the ultimate owner or beneficiary; applies only above a high threshold; data is lagged (up to 45 days after quarter-end); doesn't cover all security types or all investor types.

- NOBO/OBO Rules: Allows issuers to request lists of non-objecting beneficial owners (NOBOs) and objecting beneficial owners (OBOs) from brokers/banks holding shares in "street name."

- Limitations: Many institutional investors choose OBO status, limiting the utility for issuers seeking comprehensive identification.

- Corporate Transparency Act (CTA): Requires many unlisted companies to report BO information to FinCEN for AML purposes; this data is generally not public.

Suitability for Japan: The WG reportedly viewed the public, manager-focused nature of Form 13F as potentially excessive and not optimally designed for the primary Japanese goal of facilitating issuer-investor dialogue.

3.2. The EU Approach (Shareholder Rights Directive II - SRD II)

- Core Mechanism: SRD II grants listed companies the right to identify their shareholders. It mandates that intermediaries (custodians, brokers, etc.) across the holding chain must cooperate to transmit shareholder identity information upwards to the issuer upon request.

- Implementation Variations: National laws implementing SRD II differ:

- UK: The Companies Act 2006 (Section 793) gives public companies broad powers to demand information about any person interested in its shares. This information populates a register of interests, which is publicly accessible (though access can be restricted if requested for an improper purpose).

- France/Germany: These countries also implemented SRD II, giving issuers the right to request shareholder ID via intermediaries. However, the information obtained by the issuer is generally considered confidential and not made publicly available. The focus is on enabling the issuer to know its shareholders for communication and engagement purposes.

Suitability for Japan: The WG report indicated a leaning towards exploring mechanisms inspired by the EU SRD II model, particularly its focus on empowering the issuer to identify shareholders for engagement, rather than mandating broad public disclosure.

4. Potential Future Directions for Japan

Given that BO transparency wasn't legislated in 2024, Japan is exploring various pathways:

4.1. Non-Legislative Measures

- Stewardship Code Revisions: The most immediate step, suggested by the WG, involves revising Japan's Stewardship Code. The expectation (as noted in the Jurist PDF articles and likely actioned or in progress by mid-2025) is to strengthen the language encouraging or potentially requiring institutional investors (especially code signatories) to respond constructively to reasonable inquiries from investee companies about their beneficial ownership or voting decision-makers.

- Limitations: Relies on voluntary adherence to the Code (albeit with strong market expectations for signatories); primarily affects institutional investors; lacks legal enforcement mechanisms.

- Market Practices: Continued reliance on and potential improvement of commercial shareholder identification services, possibly with enhanced cooperation from custodian banks and transfer agents like the Japan Securities Depository Center (JASDEC).

4.2. Legislative Options

Despite being deferred in 2024, legislative solutions remain actively discussed, particularly within METI study groups potentially feeding into future Companies Act revisions. Potential models include:

- Issuer Inquiry Rights (SRD II Model): Amending the Companies Act or FIEA to grant listed companies a statutory right to request BO information concerning their shares, compelling intermediaries within the holding chain (both domestic and potentially foreign, subject to jurisdictional limits) to transmit this information up to the issuer. This aligns with the WG's apparent preference. Key design questions include:

- Scope: Which issuers get this right? What thresholds trigger identification? What level of detail (ultimate individual owner, controlling entity)?

- Process: How are requests initiated and cascaded? What are the timeframes?

- Sanctions: What penalties apply to intermediaries who fail to cooperate?

- Confidentiality: Would the information received by the issuer be kept confidential (like Germany/France) or made public (closer to UK)?

- Central BO Register: Establishing a government-maintained register of beneficial owners, perhaps linked to company incorporation or securities holding records. This model is often associated more with AML/CFT objectives (similar conceptually to the US CTA for unlisted entities) and might be less directly suited for facilitating issuer-investor dialogue unless issuers are granted specific access rights.

- Enhanced Public Disclosure: Mandating public disclosure of BO above certain thresholds, perhaps through modifications to the LSR system or a separate mechanism (closer to the US 13F concept, but potentially broader). This seems less likely given the WG's direction favoring issuer-centric information for dialogue.

Current policy discussions, as indicated by ongoing METI study groups, seem to favor exploring legislative options, likely focusing on issuer inquiry rights potentially integrated into future Companies Act amendments.

5. Challenges and Considerations

Implementing any comprehensive BO transparency regime in Japan faces significant hurdles:

- Defining "Beneficial Owner": Crafting a clear, legally robust definition that captures both ultimate economic benefit and control across diverse and complex international ownership structures (trusts, funds-of-funds, etc.) is challenging.

- Intermediary Burden: Imposing legal obligations on intermediaries (custodians, brokers, trust banks, central securities depositories) to collect, verify, maintain, and transmit accurate BO information represents a substantial operational and technological burden, especially for complex cross-border chains. Costs are a major concern.

- Cross-Border Complexity: Tracing ownership through multiple jurisdictions with differing legal requirements, data privacy laws, and levels of intermediary cooperation is extremely difficult. Effective implementation requires significant international coordination.

- Costs vs. Benefits: Policymakers must weigh the substantial implementation and ongoing compliance costs for issuers and the financial industry against the perceived (and sometimes hard to quantify) benefits of enhanced dialogue, governance, and market integrity.

- Privacy Concerns: Collecting and potentially centralizing or disclosing information about ultimate beneficial owners, particularly individuals, raises significant privacy concerns under Article 13 of the Constitution and the APPI. Robust data security, strict access controls, clear purpose limitations, and safeguards against misuse are paramount, especially if any level of public disclosure is contemplated.

- Scope and Thresholds: Determining appropriate thresholds for triggering identification/disclosure is crucial to balance transparency goals with the need to avoid overwhelming the system with information on insignificant holdings.

Conclusion

Beneficial ownership transparency stands as a significant unresolved issue in Japan's financial regulatory landscape. While the 2024 FIEA reforms addressed key aspects of TOB and LSR rules, the challenge of systematically identifying the ultimate owners behind nominee accounts and intermediary chains persists. The primary drivers for reform—facilitating meaningful investor-company dialogue and enhancing corporate governance—remain potent forces on the policy agenda.

As of mid-2025, the immediate focus appears to be on non-legislative measures, particularly strengthening expectations through the Stewardship Code for institutional investors to respond to issuer inquiries. However, the limitations of this voluntary approach are widely recognized, and active consideration of legislative solutions continues, most likely centering on granting issuers statutory rights to identify their shareholders, inspired by the EU's SRD II.

The path towards comprehensive BO legislation in Japan is fraught with challenges, including defining scope, managing intermediary burdens, navigating cross-border complexities, ensuring data privacy, and balancing costs against benefits. Yet, the alignment with global trends and the strong push from corporate governance advocates suggest that further developments are likely. International investors, intermediaries, and corporations operating in Japan should monitor policy debates and anticipate potential future requirements that could fundamentally alter how share ownership information is accessed and managed within the Japanese market. The question is no longer if Japan will move towards greater BO transparency, but rather how and when.

- Japan’s 2024 FIEA Reforms: Key Changes to Takeover Bids and Large-Shareholding Reports

- Japan Tightens Shareholder Transparency: 2024 LSR Reforms

- Mandatory Tender Offers in Japan: Expanded Scope under 2024 FIEA Amendments

- Financial Services Agency — BO Transparency Study Group Materials (JP)

https://www.fsa.go.jp/singi/bo_transparency/index.html