Behind the Corporate Mask: Japan's Supreme Court on Piercing the Corporate Veil

The principle of separate legal personality is a cornerstone of company law, meaning a company is treated as an entity distinct from its shareholders, directors, and officers. This separation generally shields those individuals from the company's liabilities. However, there are circumstances where rigidly adhering to this principle can lead to injustice or allow the corporate form to be used for improper purposes. In such situations, courts may apply the doctrine of "piercing the corporate veil" (or "disregard of legal personality," 法人格否認の法理 - hōjinkaku hinin no hōri in Japanese) to look beyond the corporate facade and hold individuals accountable or treat the company and its controller as one. A seminal Japanese Supreme Court decision on February 27, 1969, played a crucial role in formally recognizing and shaping this doctrine in Japan.

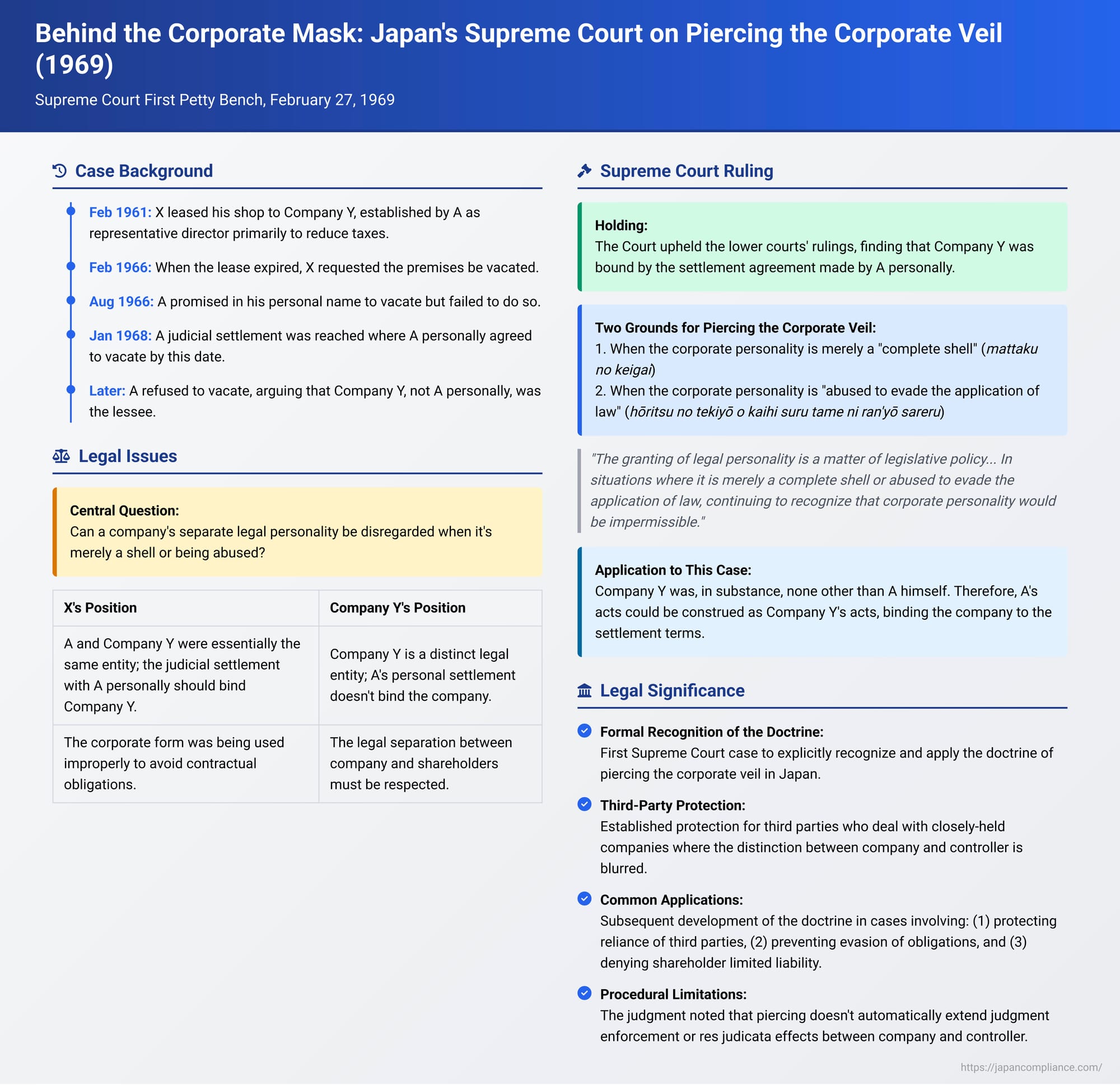

The Facts: A Shop Lease and Shifting Identities

The case involved a dispute over the lease of shop premises. In February 1961, Mr. X (the plaintiff) leased his shop to Company Y, a joint-stock company. Company Y had been established by Mr. A, who was also its representative director. The primary motivation behind forming Company Y was for Mr. A to reduce taxes related to his personal business, an "electrical shop." Mr. X, the lessor, later stated that he believed he was, in substance, leasing the premises to Mr. A for his electrical shop business, rather than to a distinct corporate entity.

When the lease term expired in February 1966, Mr. X requested that the premises be vacated. In response, Mr. A provided Mr. X with a written promise, signed in his personal name, assuring that the premises would be vacated by August 19, 1966. However, Mr. A failed to honor this commitment. Consequently, Mr. X initiated a lawsuit for eviction, naming Mr. A personally as the defendant.

During these legal proceedings, and following a recommendation from the court, a judicial settlement was reached. This settlement, formally made between Mr. X’s lawyer and Mr. A (again, seemingly in his personal capacity), stipulated that Mr. A would vacate the shop by the end of January 1968.

Despite this court-mediated settlement, Mr. A once again refused to vacate. This time, he argued that the actual lessee of the premises was Company Y, not him as an individual, and therefore the settlement with him personally did not bind the company. Frustrated by this turn of events, Mr. X then filed a new lawsuit, this time naming Company Y as the defendant, seeking eviction and payment of rent equivalent for the period of continued occupation.

Lower Courts: Focusing on the Substance

The lower courts sided with Mr. X. The Tokyo District Court (first instance) ruled in favor of Mr. X, holding that the judicial settlement, although formally involving Mr. A, effectively bound Company Y as well. The court reasoned that Mr. A, as the representative director of Company Y, had, through the settlement, committed Company Y to vacate the premises. The Tokyo High Court (appellate court) fully affirmed the first instance decision, agreeing that Company Y was obliged to comply with the terms of the settlement made by Mr. A. Company Y, maintaining that the settlement was solely between Mr. X and Mr. A personally and did not involve the company, appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Endorsement of Piercing the Veil

The Supreme Court, in its First Petty Bench judgment of February 27, 1969, dismissed Company Y's appeal and upheld the lower courts' rulings. This decision is renowned for its articulation of the principles underlying the doctrine of piercing the corporate veil in Japan.

I. Rationale for Corporate Personality and Its Disregard:

The Court began by explaining the nature of corporate personality.

- It stated that the granting of legal personality to a social organization is a matter of "legislative policy," based on an evaluation of the entity's societal worth and a determination that it merits being recognized as a legal subject. It is, essentially, a "legal technique."

- Therefore, the Court reasoned, in situations where the corporate personality is merely a "complete shell" (全くの形骸にすぎない場合 - mattaku no keigai ni suginai baai), or where it is "abused for purposes such as evading the application of law" (法律の適用を回避するために濫用されるが如き場合 - hōritsu no tekiyō o kaihi suru tame ni ran'yō sareru ga gotoki baai), to continue to recognize that distinct corporate personality would be impermissible in light of the original purpose of granting such personality. In these instances, disregarding the corporate entity is "demanded."

II. One-Person Companies and Third-Party Protection:

The Court specifically addressed the context of closely-held companies, particularly relevant given the nature of Company Y.

- It observed that joint-stock companies (kabushiki kaisha) can be established relatively easily under Japan's normative system of incorporation, and that even "one-person companies" (where a single individual effectively owns and controls the company) are possible.

- This ease of formation can lead to situations where the corporate structure becomes a mere "straw man" (藁人形 - wara-ningyō), where the company is, in substance, the individual, and the individual is the company. The business is, for all practical purposes, a personal enterprise operating under a corporate guise.

- In such cases, third parties dealing with these entities may often find it unclear whether they are transacting with the company as a separate legal person or with the individual behind it. This ambiguity necessitates legal mechanisms to protect these third parties. The Court stated that when the need arises to "reach the individual who is the real substance behind the corporate legal form," a third party can disregard the corporate personality and treat a transaction made in the company's name as an act of the individual controller. Conversely, an act done in the individual’s name could be treated as an act of the company. This is necessary because otherwise, individuals could use the corporate form to unfairly harm the interests of those they deal with.

III. Application to the Instant Case:

Applying these principles, the Supreme Court found:

- Although Company Y adopted the form of a joint-stock company, its "substance was none other than Mr. A, the individual existing behind it."

- Given this, Mr. X was entitled to demand rent from Mr. A personally and could also sue Mr. A personally for eviction. (The Court added a parenthetical but important clarification: the res judicata effect—the binding nature of a final judgment on the parties—of a judgment against Mr. A personally regarding eviction would not automatically extend to Company Y. This procedural aspect, it noted, requires separate consideration. )

- Therefore, the judicial settlement reached between Mr. X and Mr. A, even though formally made in Mr. A's personal name, could, under these circumstances, be "construed as an act of Company Y."

- Consequently, Company Y was indeed obligated by the terms of that settlement to vacate the premises by the end of January 1968.

The Doctrine of Piercing the Corporate Veil in Japanese Law

This 1969 Supreme Court judgment is considered a landmark because it explicitly recognized and applied the doctrine of piercing the corporate veil, a concept largely developed in Anglo-American case law, within the Japanese legal system.

- Grounds for Piercing the Veil: The judgment identified two primary situations where disregarding the corporate personality might be justified:

- Where the "corporate personality is merely a complete shell" (法人格が全くの形骸にすぎない場合 - hōjinkaku ga mattaku no keigai ni suginai baai). This is often referred to as the "shell company" or "alter ego" scenario.

- Where the corporate personality is "abused for purposes such as evading the application of law" (法律の適用を回避するために濫用されるが如き場合 - hōritsu no tekiyō o kaihi suru tame ni ran'yō sareru ga gotoki baai). This category is broadly termed "abuse of corporate personality" (hōjinkaku no ran'yō) and encompasses not only the evasion of statutes but also attempts to evade contractual obligations or defraud creditors.

- Traditional Interpretations and Scholarly Critique:

- Traditional academic interpretations in Japan often distinguished these two grounds. "Abuse" was typically seen as involving an illegal or improper motive on the part of the person controlling the company. "Shell" or "formalistic existence" (keigaika) was understood to involve complete domination of the company by its shareholders (often a single shareholder), coupled with formal irregularities such as the non-holding of shareholder or board meetings, non-issuance of share certificates, commingling of personal and corporate assets and affairs, and lack of independent corporate activity.

- However, prominent legal scholars have criticized these broad, all-encompassing categories of "abuse" and "shell" as being too vague and potentially obscuring the underlying legal issues. These critics argue that courts should first attempt to resolve such cases by applying specific statutory provisions (e.g., fraudulent conveyance laws) or through the interpretation of contracts. Only when these avenues are insufficient should a more general doctrine like piercing the veil be invoked, and even then, the criteria for its application should be clarified based on the specific legal context and the purposes of the underlying laws or norms being threatened. Today, a majority of academic opinion appears to have largely accepted these critical perspectives, advocating for a more nuanced, type-specific approach.

Common Scenarios for Piercing the Corporate Veil

Following the critical approach, Japanese legal scholarship and lower court practice have explored several distinct types of situations where piercing the corporate veil might be considered:

- Protecting the Reliance and Expectations of Third Parties:

This was the scenario in the 1969 Supreme Court case itself. Mr. X was, to some extent, unclear whether his true counterparty was Company Y or Mr. A personally, and the behavior of Mr. A/Company Y did little to clarify this distinction. The Court acted to protect Mr. X's reasonable expectations that arose from this ambiguity and Mr. A's personal assurances. The PDF commentary notes that the extent to which a party's mere subjective lack of clear recognition of the counterparty's identity should be protected can be a difficult question in other contexts. A related situation involves a third party who knows they are dealing with a company but relies on an expectation (perhaps induced by the controlling shareholder) that the shareholder will personally guarantee the company's obligations. The key here is often the nature and explicitness of any representations made by the controller. - Preventing the Evasion of Contractual or Legal Obligations:

This is a distinct category where the corporate form is used to circumvent duties or liabilities. A leading Supreme Court case following the 1969 decision (judgment of October 26, 1973) involved a company transferring its assets to a newly established company to shield them from the original company's creditors. In such cases, courts often scrutinize factors like the identity of controllers, officers, and employees between the old and new companies; the continuation of the same business; the nature of asset transfers (especially if for inadequate consideration); and whether creditors were consulted. It's also important to note that other statutory remedies, such as actions to set aside fraudulent conveyances (Article 424 of the Civil Code) or the liability of a business transferee who continues to use the transferor's trade name (Article 22 of the Companies Act), may also be available. Piercing the veil might also be considered to prevent the evasion of non-competition clauses in contracts or obligations under labor law. - Denial of Shareholder Limited Liability:

This application of the doctrine aims to protect company creditors by holding shareholders (especially controlling ones) personally liable for the company's debts, thereby overriding the usual principle of limited liability. The critical question is under what specific circumstances this drastic measure is justified.- Early lower court cases often focused on formalistic indicators of a "shell" company—such as non-compliance with statutory procedures, commingling of assets, lack of independent employees or assets—to justify imposing liability on controlling shareholders. However, these formal aspects may not always directly relate to the harm suffered by creditors, making them less robust as sole criteria.

- More influential academic theories emphasize two substantive grounds for denying limited liability: exploitation of the company by shareholders (e.g., asset stripping, siphoning off corporate opportunities, or engaging in transactions unfairly disadvantageous to the company for the shareholder's benefit) and gross undercapitalization where the company is set up with clearly insufficient capital to meet its foreseeable business risks and liabilities. While many court decisions that pierce the veil mention the company's low capitalization or lack of assets, some scholars argue that undercapitalization alone, without other factors like misrepresentation or exploitation, is an insufficient basis to disregard limited liability.

Procedural Implications of Piercing the Veil

An important aspect of the doctrine concerns its procedural effects. The 1969 Supreme Court judgment itself, while holding Company Y substantively bound by Mr. A's actions in that specific context (the settlement), explicitly stated that a judgment obtained solely against Mr. A concerning the eviction would not automatically have res judicata (claim preclusion) effect against Company Y. This means a new legal action might be needed against the company itself. Similarly, a later Supreme Court case (September 14, 1978) denied the automatic extension of the enforcement power of a judgment (e.g., a monetary judgment against an individual) to the assets of a company controlled by that individual, purely on piercing grounds, without a specific judgment against the company. However, the doctrine has been successfully invoked in the context of third-party objection suits (where a third party claims ownership of property seized to satisfy a judgment against another).

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's February 27, 1969, decision was a pivotal moment in Japanese company law. It formally imported and legitimized the doctrine of piercing the corporate veil, providing Japanese courts with a flexible equitable tool to prevent injustice when the corporate form is misused or when the lines between a closely-held company and its individual controller become indistinguishably blurred. While the precise criteria for its application continue to be debated and refined through scholarly discussion and subsequent case law, this foundational judgment established that Japanese law will not permit the legal technicality of separate corporate personality to be used as an instrument of fraud or to achieve results that are fundamentally unfair to third parties. It underscored the principle that the law will, in appropriate circumstances, look to the underlying substance rather than merely the form.