Bank's Set-Off Rights in Bankruptcy: The "Cause Existing Before" Crisis – A 1965 Japanese Supreme Court Ruling

In the landscape of Japanese bankruptcy law, the right of set-off (相殺 - sōsai) serves as a vital, albeit carefully regulated, mechanism. It allows a party who is both a creditor and a debtor to a bankrupt entity to net out their mutual obligations. This can effectively provide the creditor with a form of preferential payment on their claim, up to the amount of the debt they themselves owed to the bankrupt's estate. However, to maintain fairness among all creditors, the Bankruptcy Act imposes certain restrictions on this right, particularly concerning claims acquired or debts incurred when the creditor already knew of the bankrupt's burgeoning financial crisis (typically marked by a "suspension of payments" - 支払停止, shiharai teishi, or the filing of a bankruptcy petition).

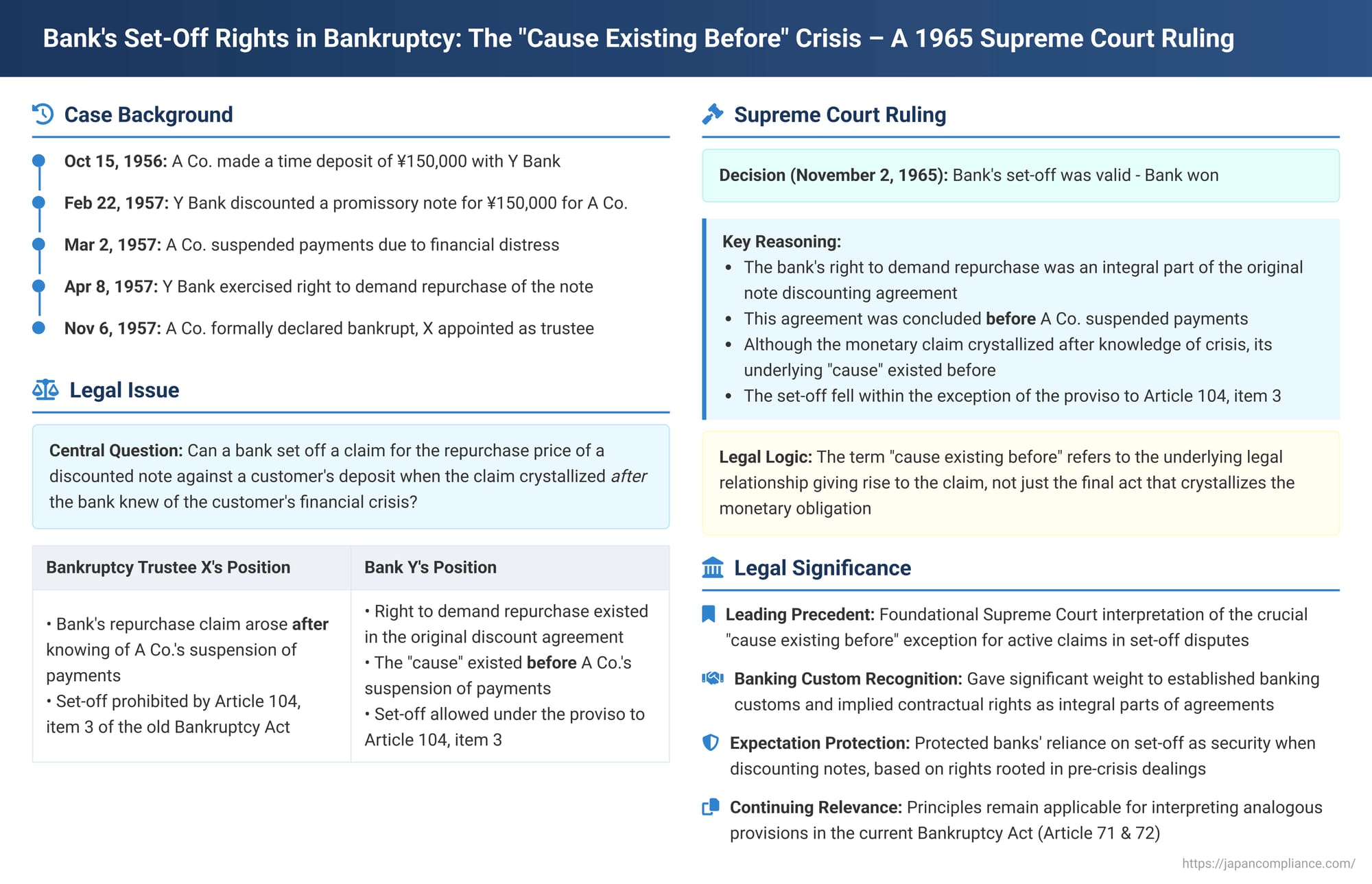

A crucial exception to these restrictions allows set-off if the claim or debt in question, though crystallizing after knowledge of the crisis, arose from a "cause existing before" such knowledge. A foundational Supreme Court of Japan decision from November 2, 1965, provided a key interpretation of what constitutes such a "cause existing before," particularly in the common banking scenario involving a bank's right to demand repurchase of a discounted promissory note from a customer who subsequently becomes insolvent.

Factual Background: Discounted Note, Suspension of Payments, and Bank's Set-Off

The case involved A Co., a customer of Y Bank.

- On October 15, 1956, A Co. made a time deposit of 150,000 yen with Y Bank, thereby creating a claim for A Co. against Y Bank (this would become the passive claim for set-off purposes).

- On February 22, 1957, Y Bank, at A Co.'s request, discounted a promissory note for 150,000 yen. This note had been drawn by a third party (B Co.) and was payable to A Co.; its maturity date was May 24, 1957. By discounting the note, Y Bank effectively purchased it from A Co. for a sum less than its face value, providing A Co. with immediate funds. Y Bank then held the note, expecting to collect from B Co. at maturity.

- Shortly thereafter, on March 2, 1957, A Co. found itself in financial distress and suspended its payments.

- Several months later, on November 6, 1957, A Co. was formally declared bankrupt under Japan's (then) old Bankruptcy Act, and X was appointed as its bankruptcy trustee.

Trustee X subsequently sued Y Bank, demanding payment of A Co.'s 150,000 yen time deposit. Y Bank, in its defense, asserted a right of set-off. Y Bank's argument was multifaceted:

- It claimed that based on established banking custom (or as an implied term of the note discounting agreement), when a bank discounts a promissory note for a customer, the bank acquires a "right to demand repurchase" (手形買戻請求権 - tegata kaimodoshi seikyūken) of that note from the customer if the customer's creditworthiness subsequently deteriorates (e.g., upon a suspension of payments). This right allows the bank to effectively "sell back" the discounted note to the customer for its face value, thereby crystallizing a monetary claim against the customer.

- Y Bank asserted that on April 8, 1957—which was after A Co. had suspended its payments and after Y Bank had become aware of this suspension, but before A Co. was formally declared bankrupt—it had exercised this right to demand repurchase of the subject discounted note from A Co.

- This exercise, Y Bank argued, created a monetary claim for 150,000 yen (the note's face value) in its favor against A Co. (this was Y Bank's active claim for set-off).

- Y Bank then declared its intention to set off this 150,000 yen note repurchase price claim against A Co.'s 150,000 yen time deposit claim (which was Y Bank's passive obligation to A Co.'s estate).

The Osaka District Court (first instance) upheld Y Bank's set-off defense and dismissed trustee X's claim for the deposit. On appeal, the Osaka High Court also sided with Y Bank and dismissed X's appeal. The High Court found that:

- A banking custom indeed existed allowing banks to demand repurchase of discounted notes if the discount client's financial condition worsened (such as through a suspension of payments).

- This right to demand repurchase, though conditional upon such credit deterioration and the bank's subsequent demand, fundamentally originated at the time of the initial note discounting agreement.

- Therefore, even though Y Bank exercised its repurchase right and its monetary claim against A Co. thereby crystallized after Y Bank knew of A Co.'s suspension of payments, the underlying cause for this claim (i.e., the original note discounting agreement which implicitly or customarily included this repurchase right) existed before Y Bank acquired such knowledge.

- Consequently, the High Court concluded that Y Bank's set-off was permissible under the proviso to Article 104, item 3, of the old Bankruptcy Act, which allowed set-off if the active claim was acquired based on a "cause existing before" knowledge of the debtor's crisis.

Trustee X then appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

The Legal Issue: Was the Bank's Repurchase Claim Based on a "Cause Existing Before" Its Knowledge of the Crisis?

The central legal question for the Supreme Court was the interpretation of the proviso in Article 104, item 3, of the old Bankruptcy Act. This provision generally prohibited a creditor from setting off a claim against the bankrupt if that claim was acquired after the creditor knew of the bankrupt's suspension of payments or that a bankruptcy petition had been filed. However, the proviso carved out an exception: this prohibition did not apply if the claim was acquired based on a "cause existing before" (支払ノ停止若ハ破産ノ申立アリタルコトヲ知リタル時ヨリ前ニ生シタル原因ニ基キ - shiharai teishi mata wa hasan no mōshitate aritaru koto o shiritaru toki yori mae ni shōjitaru gen'in ni motozuki) the creditor had such knowledge.

In this case, Y Bank's definite monetary claim for the repurchase price of the note came into being (crystallized) only when it made the demand for repurchase on April 8, 1957, which was after it knew of A Co.'s March 2, 1957, suspension of payments. However, did the legal basis or "cause" for this claim already exist before Y Bank learned of the suspension? The High Court had found that it did, rooting it in the original note discounting agreement.

The Supreme Court's Ruling: Original Discount Agreement Constitutes the "Cause Existing Before"

The Supreme Court, in its judgment of November 2, 1965, dismissed trustee X's appeal, thereby upholding Y Bank's right to set off.

The Court affirmed the High Court's legal reasoning:

- Existence of Repurchase Right from Discount Agreement: The Supreme Court accepted the High Court's finding that a banking custom (or an implied term of the contract) existed whereby a bank, upon discounting a promissory note, acquires a right to demand its repurchase from the discount client if that client's creditworthiness deteriorates. This right was considered an integral part of the original note discounting transaction.

- Distinction Between Origin of Right and Crystallization of Monetary Claim: The Court acknowledged that Y Bank's specific monetary claim against A Co. for the repurchase price of the note only arose or crystallized when Y Bank actually exercised its right to demand repurchase.

- Original Discount Agreement as the Pre-Existing "Cause": However, the Supreme Court emphasized that the underlying right to make that repurchase demand itself originated from, and was legally caused by, the promissory note discounting agreement entered into on February 22, 1957. This agreement was concluded before A Co. suspended its payments on March 2, 1957, and therefore before Y Bank became aware of A Co.'s financial crisis.

- Conclusion on Set-Off Permissibility: Consequently, the Supreme Court held that Y Bank's monetary claim for the repurchase price, despite crystallizing after Y Bank had knowledge of A Co.'s suspension of payments, was properly deemed to have been "acquired based on a cause existing before" Y Bank obtained such knowledge. The "cause" was the original note discounting agreement, which included, either expressly or by established custom, the bank's right to demand repurchase under circumstances of the client's credit deterioration.

- Therefore, the set-off exercised by Y Bank was permissible under the exception provided in the proviso to Article 104, item 3, of the old Bankruptcy Act. The High Court's legal interpretation was correct.

Significance of the "Cause Existing Before" Interpretation

This 1965 Supreme Court judgment is a foundational decision in Japanese bankruptcy law regarding the scope of set-off rights:

- Leading Precedent on "Cause Existing Before": It stands as a key early Supreme Court precedent interpreting the crucial "cause existing before" exception to the general rules restricting set-off when a creditor's active claim (the claim they wish to set off) is acquired after they become aware of the debtor's financial crisis. While a subsequent 1988 Supreme Court case (Showa 59 (O) No. 557, discussed as "BK65") addressed the "cause existing before" in relation to the passive claim (the debt owed by the creditor to the bankrupt), this 1965 decision focused on the active claim held by the creditor.

- Recognition of Banking Custom and Implied Contractual Rights: The decision gave significant weight to established banking customs, treating the bank's right to demand repurchase of discounted notes upon a client's credit deterioration as an integral part of the discount agreement, even if not always explicitly spelled out in every detail. This right was seen as the "cause" for the later monetary claim.

- Protection of Bank's Expectation of Set-Off: The ruling effectively protects a bank's reliance on its ability to utilize set-off against a customer's deposits as a form of security when it discounts promissory notes for that customer. The underlying rationale is that the bank's expectation of set-off, formed at the time of the initial transaction (the discounting of the note), is a legitimate one deserving of protection, provided the right to generate the set-off claim was rooted in that pre-crisis dealing.

- Distinction from Acquiring "New" Claims Post-Knowledge: This situation is fundamentally different from a creditor attempting to acquire entirely new claims against the debtor (e.g., by purchasing them from a third party) after already knowing of the debtor's insolvency, which would generally be prohibited from set-off to prevent unfair maneuvering. Here, the bank's claim, although its monetary form crystallized later, was directly linked to and derived from its pre-crisis contractual relationship with the bankrupt.

- Relevance to Current Bankruptcy Law: The principles enunciated in this 1965 judgment continue to be relevant for interpreting the analogous "cause existing before" exceptions found in the current Japanese Bankruptcy Act (specifically, Article 71, paragraph 2, item (b) and Article 72, paragraph 2, item (b)). These provisions also allow set-off for claims acquired or debts incurred after knowledge of crisis if they are based on a cause that existed before such knowledge.

- Evolution of Banking Agreements: The PDF commentary notes that modern standard banking transaction agreements have evolved. Many now include clauses stipulating that a customer's obligation to repurchase discounted notes arises automatically upon certain events, such as the customer's suspension of payments, without the bank needing to make a separate demand. Under such modern agreements, the bank's repurchase claim against the customer would arguably arise even more clearly before or at the very moment of the customer's financial crisis. This could make the application of the "cause existing before" analysis for set-off purposes more straightforward, or in some cases, might even mean the claim itself is considered to have arisen before the creditor's knowledge of the crisis, thus not falling under the initial set-off prohibition in the first place.

Concluding Thoughts

The Supreme Court's 1965 decision provides an enduring interpretation of the "cause existing before" exception crucial for determining set-off rights in Japanese bankruptcy. It clarified that a bank's claim against a bankrupt customer for the repurchase price of a discounted promissory note can be validly set off against the customer's deposits, even if the bank's formal demand for repurchase (which crystallizes the monetary claim) occurs after the bank learns of the customer's suspension of payments. This is permissible as long as the bank's underlying right to demand such repurchase originated from the pre-crisis note discounting agreement itself, which is deemed the "cause existing before" the bank's knowledge of the crisis. This ruling underscores the significance of the foundational contractual relationship in assessing set-off rights and serves to protect the reasonable expectations of creditors based on their established pre-crisis dealings with the debtor.