Bank's Duty to Explain Derivatives: How 'Simple' is a Plain Vanilla Interest Rate Swap? A Japanese Supreme Court View

Judgment Date: March 7, 2013

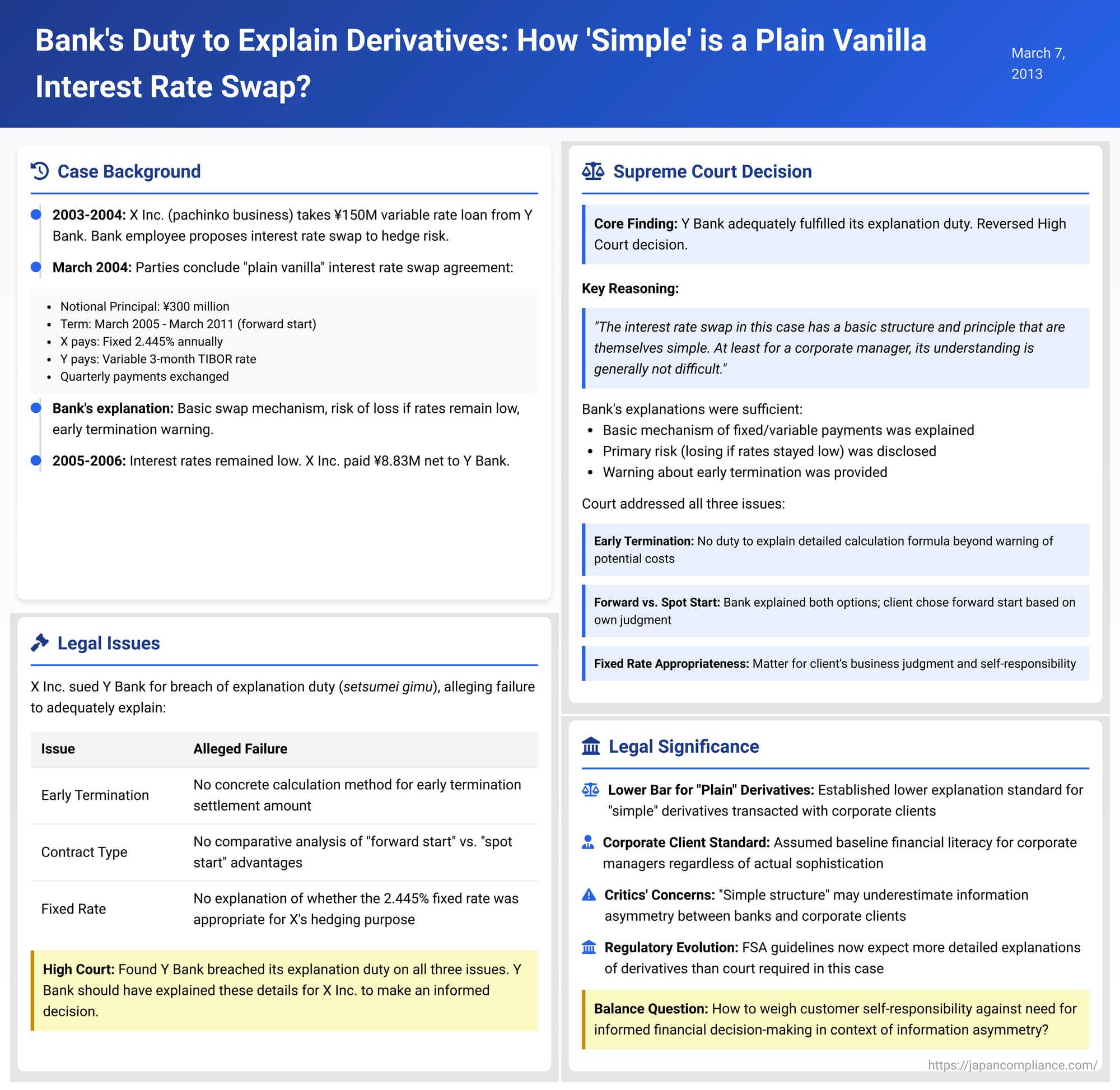

Financial derivatives, such as interest rate swaps, can be valuable tools for businesses looking to manage financial risks, like fluctuations in interest rates on their loans. However, these instruments also carry their own set of risks and complexities. This raises a critical legal question: what is the extent of a bank's duty to explain these products to its corporate clients, especially when the product is considered a relatively standard "plain vanilla" type? The Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench, addressed this issue in a notable judgment on March 7, 2013 (Heisei 23 (Ju) No. 1493), providing its perspective on the scope of necessary explanations.

The Interest Rate Swap Deal: A Hedge That Soured

The plaintiff, X Inc., a company operating pachinko parlors, had significant borrowings from various banks, mostly at variable interest rates. In late 2003, X Inc. took out an additional loan of ¥150 million from the defendant, Y Bank (a major Japanese "mega-bank"), also at a variable interest rate linked to the short-term prime rate. Recognizing that X Inc. was heavily exposed to variable rates, B, an employee of Y Bank, proposed an interest rate swap transaction as a way for X Inc. to hedge against the risk of future interest rate increases.

The proposed product was a "plain vanilla" interest rate swap. In such a transaction, two parties agree to exchange interest payments based on a notional principal amount for a set period. Typically, one party pays a fixed interest rate, while the other pays a floating (variable) interest rate. No actual principal is exchanged; only the net difference in the calculated interest payments is settled periodically.

In March 2004, X Inc. and Y Bank concluded the interest rate swap agreement ("the Contract"). The key terms were:

- Notional Principal: ¥300 million.

- Transaction Period: From March 8, 2005, to March 8, 2011. This was a "forward start" swap, meaning the exchange of interest payments would begin approximately one year after the contract was signed.

- Payment Terms: Every three months during the transaction period:

- X Inc. would pay Y Bank an amount equivalent to a fixed annual interest rate of 2.445% applied to the ¥300 million notional principal.

- Y Bank would pay X Inc. an amount equivalent to the prevailing 3-month TIBOR (Tokyo Interbank Offered Rate, a standard variable benchmark) applied to the same ¥300 million notional principal.

The proposal document provided by Y Bank to X Inc. explained the basic mechanism of the swap, stated that profit or loss would depend on future movements in the variable interest rate, and included examples and a profit/loss simulation based on then-current rates (TIBOR at 0.09%, short-term prime at 1.375%). It highlighted the merit of fixing future borrowing costs to hedge against rate rises, but also noted the demerit: if variable rates fell or remained low, X Inc. might end up paying more than it would have without the swap. Crucially, the proposal also contained a warning: "Early termination of this contract after agreement is, in principle, not possible. If, due to unavoidable circumstances, early termination is made with our bank's consent, you (X Inc.) may be required to pay our bank an amount calculated by our bank's prescribed method based on market conditions at the time of termination."

C President, X Inc.'s representative, after initial explanations from B, requested a further session with X Inc.'s tax advisor present. During this second meeting, B explained both "spot start" (payments begin immediately) and "forward start" options. C President, reportedly believing that interest rates would not rise in the immediate future, opted for the 1-year forward-start swap. Subsequently, the fixed rate of 2.445% was agreed upon, and C President signed a document acknowledging his understanding of the transaction and its associated risks.

Unfortunately for X Inc., variable interest rates (TIBOR) remained low after the swap's payment period began in March 2005. As a result, between June 2005 and June 2006, X Inc. was obliged to make net payments to Y Bank totaling over ¥8.83 million, as the fixed rate it paid significantly exceeded the floating rate it received.

The Legal Challenge: Alleged Failures in the Bank's Explanation

X Inc. sued Y Bank for damages, alleging that the bank had breached its duty of explanation (説明義務 - setsumei gimu) when proposing and concluding the swap agreement, and that this breach constituted a tort.

The Fukuoka High Court (acting as the second instance court) ruled in favor of X Inc. It found that Y Bank had indeed failed in its duty to explain by not adequately addressing three specific points:

- The concrete calculation method for the settlement amount (penalty) that might be required upon early termination of the swap.

- The comparative advantages and disadvantages of choosing a "forward start" type swap versus a "spot start" type.

- Whether the agreed-upon fixed interest rate of 2.445% was appropriate for X Inc.'s stated purpose of hedging its interest rate risk.

The High Court reasoned that if Y Bank had properly explained these matters, X Inc. would have understood the potentially limited hedging effectiveness of the swap under the prevailing conditions and would likely not have entered into the contract. Y Bank appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Reversal: A More Limited View of the Bank's Explanation Duty for "Simple" Derivatives

The Supreme Court overturned the High Court's decision, ruling that Y Bank had not breached its duty of explanation concerning the three points identified by the High Court.

The Supreme Court's core reasoning was based on its characterization of the plain vanilla interest rate swap and the general understanding expected of a corporate client:

- "Simple Structure, Understandable by Corporate Managers": The Court stated that the type of interest rate swap in this case—where the outcome depends solely on the accuracy of predictions about future interest rate movements—has a "basic structure and principle [that] are themselves simple." It further opined that, "at least for a corporate manager, its understanding is generally not difficult," and imposing the risk of such a contract on a company is not inherently problematic.

- Bank's Core Explanation Deemed Sufficient: The Supreme Court found that Y Bank had provided an adequate explanation of the fundamental aspects of the transaction. Specifically, Y Bank had explained:

- The basic mechanism of the swap (the exchange of fixed-rate payments for variable-rate payments on a notional principal).

- The contractually set fixed interest rate and the variable interest rate benchmark (3-month TIBOR).

- The primary risk involved: that X Inc. would end up making net payments to Y Bank (i.e., the fixed rate paid by X Inc. would be higher than the variable rate received from Y Bank) if the variable interest rate did not rise above a certain level.

Based on these explanations, the Supreme Court concluded that Y Bank had "basically fulfilled its duty of explanation."

Addressing the three specific points of alleged non-explanation that the High Court had focused on:

- Early Termination Settlement Calculation: The Supreme Court noted that Y Bank's proposal document had clearly stated that early termination was, in principle, not permitted without Y Bank's consent. It also explicitly warned that if early termination were allowed, X Inc. might be required to pay a settlement amount based on prevailing market conditions and Y Bank's prescribed calculation method. The Supreme Court held that Y Bank had no further legal duty to explain the specific, detailed calculation formula for this potential termination penalty.

- Pros and Cons of Forward-Start vs. Spot-Start Options: Y Bank had explained both types of start dates to X Inc. The decision to choose the 1-year forward-start option was made by C President on behalf of X Inc., based on his own assessment that interest rates were unlikely to rise in the short term. The Supreme Court found that Y Bank had no additional duty to elaborate on the comparative advantages or disadvantages of this choice beyond presenting the options.

- Appropriateness of the Fixed Interest Rate Level: The Court deemed the question of whether the agreed-upon fixed rate of 2.445% was an appropriate or effective level for X Inc.'s hedging needs to be a matter for X Inc.'s own business judgment and self-responsibility. It was not Y Bank's duty to provide an opinion or detailed analysis on this commercial aspect of the transaction.

Thus, the Supreme Court concluded that Y Bank's failure to provide detailed explanations on these three specific points did not constitute a breach of its explanation duty. Consequently, the contract was valid and X Inc.'s claim for damages was dismissed.

Analyzing the "Simple Structure" Rationale and Its Implications

The Supreme Court's emphasis on the "basically simple structure" of a plain vanilla interest rate swap and its general understandability for "corporate managers" has been a focal point of subsequent legal discussion and has influenced lower court decisions in similar cases involving derivatives.

- Impact on Later Cases: This "simple structure, generally not difficult for corporate managers to understand" reasoning has been subsequently cited by lower courts in Japan when assessing banks' explanation duties in other derivative transactions with corporate clients, often leading to findings that the bank did not breach its duty. This has included cases involving currency options and other types of swaps.

- Criticism of the "Simplicity" Argument: Some legal commentators and financial experts have expressed concern about this characterization. They argue that while the basic concept of exchanging fixed for floating interest payments might appear straightforward, understanding the true economic implications, risks, and fairness of the specific terms of a given swap—such as the appropriateness of the fixed rate relative to market benchmarks, the embedded costs or profit margins for the bank, or the complex dynamics of how early termination values are calculated—requires a sophisticated level of financial knowledge that many corporate managers, particularly those in small to medium-sized enterprises without dedicated financial expertise, may not possess. The inherent information asymmetry between a large financial institution and its corporate client often remains significant.

- The Missing "Why" and Economic Value: Critics suggest that the Supreme Court's assessment may have focused too much on what the swap does at a conceptual level, and not enough on whether the bank provided sufficient information for the client to judge why the specific terms offered were suitable or represented fair market value. For instance, without understanding how the proposed fixed rate (2.445% in this case) related to prevailing market swap rates or benchmarks for similar transactions, it would be difficult for a client to assess the economic value or potential cost of the swap.

- Customer Sophistication Still Matters: While the Supreme Court used the general term "corporate manager," it's important to note that the ruling did not delve into a detailed analysis of X Inc.'s specific financial acumen or experience with derivatives. Legal commentators generally agree that the scope and method of a financial institution's explanation duty should ideally be tailored to the customer's actual attributes, including their financial literacy, investment experience, and stated objectives. A blanket assumption that a particular product is "simple" for all corporate managers might not always hold true.

The Broader Context of Financial Product Explanation Duties in Japan

Financial institutions in Japan are subject to a duty to explain when selling financial products, arising from both general principles of good faith in contract law and specific statutory provisions, most notably the Financial Instruments and Exchange Act (FIEA - 金融商品取引法). The FIEA, for instance, prohibits soliciting investment without explaining key aspects like the nature of the transaction and risks of loss due to market fluctuations.

Furthermore, the Financial Services Agency (FSA - 金融庁) issues supervisory guidelines that, while not law themselves, set out regulatory expectations for financial institutions. Interestingly, current FSA guidelines for major banks do expect them to provide more concrete and understandable explanations regarding derivative product contents, risks, and, specifically, early termination procedures and settlement payments. This suggests that regulatory expectations regarding the level of detail for explanations, particularly concerning early termination costs, may have evolved since this 2013 Supreme Court judgment.

The ongoing challenge for both financial institutions and the legal system is to find the right balance between fostering customer self-responsibility in financial decision-making and ensuring that customers are provided with adequate, fair, and understandable information to make those decisions, especially when dealing with products that, despite appearing "plain vanilla" on the surface, can have complex and significant financial consequences.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's March 2013 decision in the X Inc. v. Y Bank case indicates that for what it deemed "basically simple" derivative products like plain vanilla interest rate swaps transacted with corporate clients, a bank's duty of explanation is largely fulfilled by clearly outlining the fundamental mechanism of the product and its primary financial risks. The Court placed significant emphasis on the client's self-responsibility in assessing the commercial wisdom of the transaction's specific terms, such as the appropriateness of the fixed rate or the choice between different start dates, and did not require banks to explain the detailed calculation methodology for potential early termination penalties beyond a general warning. While providing a degree of legal certainty for banks in such transactions, the ruling also sparked debate about the actual level of understanding possessed by corporate clients and the appropriate scope of information needed for truly informed decision-making in the derivatives market.