Bank Secrecy vs. The Search for Truth: Japan's Supreme Court on Disclosure of Customer Records in Litigation

Judgment Date: December 11, 2007

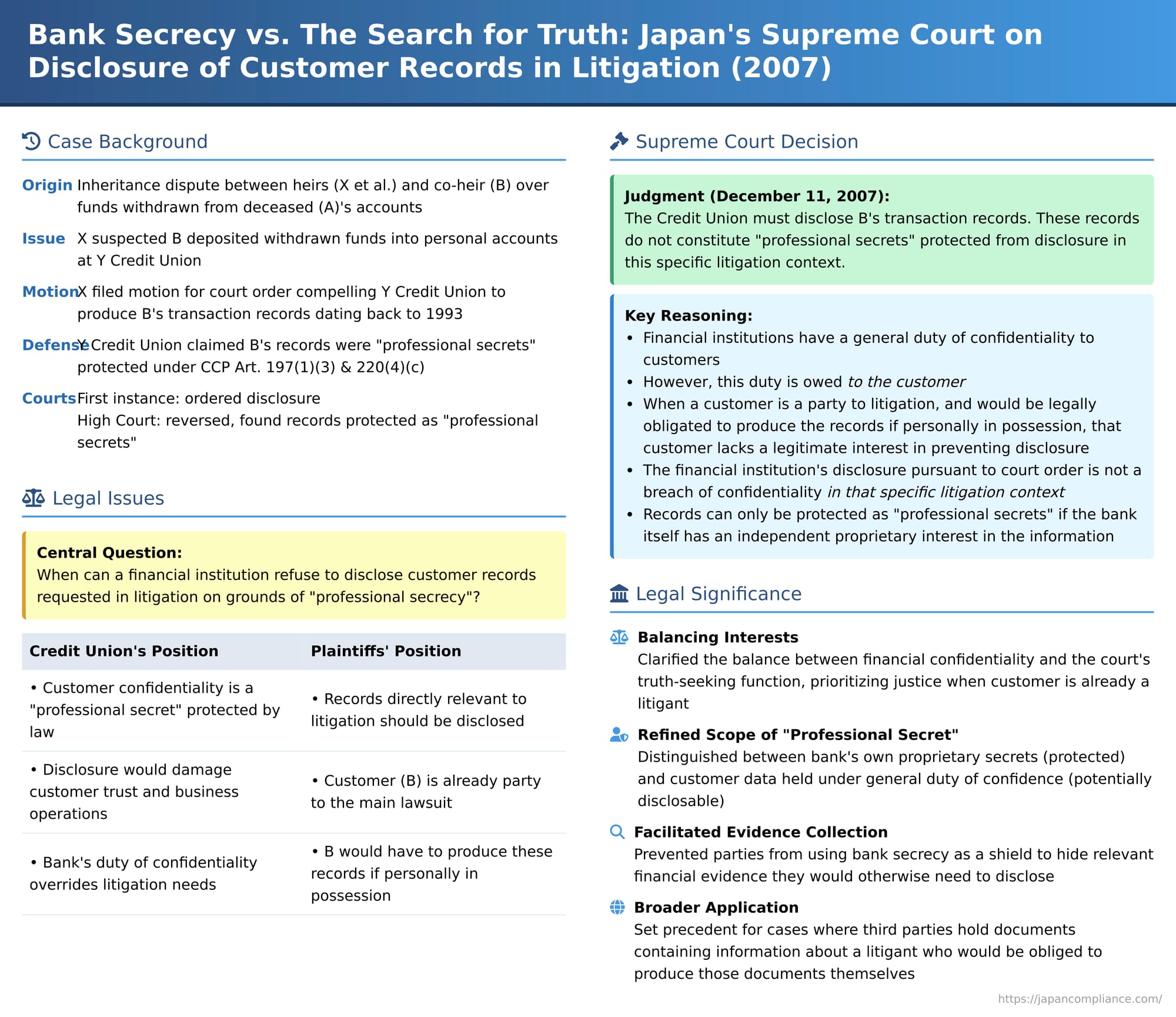

Financial institutions operate under a strong expectation, and often a legal or contractual duty, of confidentiality regarding their customers' information. This bank secrecy is crucial for maintaining trust. However, this duty can come into conflict with the justice system's need for evidence when customer records become relevant to civil litigation, particularly if the customer themselves is a party to that lawsuit. A key decision by the Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench, on December 11, 2007 (Heisei 19 (Kyo) No. 23), addressed this tension, clarifying when a financial institution can be compelled to produce customer transaction records despite claims of "professional secrecy."

The Underlying Dispute: An Inheritance Battle and a Hunt for Assets

The main legal battle that gave rise to this specific document production dispute was an inheritance case. The plaintiffs, X et al., were heirs of the deceased, A. They sued a co-heir, B, claiming their rightful share of A's estate. A central point of contention was whether funds that B had withdrawn from A's bank accounts during A's lifetime were used for A's legitimate expenses, or whether B had improperly received these funds as a gift (constituting a "special benefit" potentially reducing B's inheritance share) or had misappropriated them (making B liable to the estate for unjust enrichment or tort damages).

X et al. believed that B had deposited these disputed funds into B's own personal bank accounts held at Y Credit Union ("the Credit Union"). To prove this, X et al. filed a motion in the main lawsuit seeking a court order compelling the Credit Union (which was not a party to the main inheritance dispute) to produce B's transaction records ("the Records" - 本件明細表) dating back to 1993.

The Document Production Motion and the "Professional Secret" Defense

The Credit Union opposed the motion, arguing that it was not obligated to produce the Records. Its primary defense was that B's transaction history constituted a "professional secret" (職業の秘密 - shokugyō no himitsu) protected under Article 197, Paragraph 1, Item 3 of Japan's Code of Civil Procedure (CCP). This article allows individuals to refuse to testify about matters concerning technical or professional secrets. By extension, CCP Article 220, Paragraph 4, Item (c) allows the holder of a document containing such professional secrets to refuse its production. The Credit Union asserted its duty of confidentiality to its customer, B, and argued that disclosing such information would breach customer trust and thereby harm its business operations.

The lower courts diverged on this issue:

- The court of first instance (handling the document production motion) granted X et al.'s request and ordered the Credit Union to produce B's records. It found that the records did not qualify as a protected professional secret in this context.

- The High Court, however, upon the Credit Union's appeal of the production order, reversed this decision. It sided with the Credit Union, reasoning that maintaining customer confidentiality was vital for the bank's business, and that disclosure of transaction histories could indeed undermine customer trust and disrupt operations. The High Court thus deemed the records to be protected professional secrets. It also commented that X et al.'s request seemed somewhat "exploratory" and that the indispensability of the records for proving their case had not yet been sufficiently established. X et al. then brought a special appeal of this High Court decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Decision: Defining the Limits of Bank Confidentiality in Litigation

The Supreme Court overturned the High Court's decision and reinstated the order for the Credit Union to produce B's transaction records. The Court's reasoning carefully distinguished between a financial institution's general duty of confidentiality and the specific application of "professional secrecy" in litigation involving its customer.

- Bank's General Duty of Confidentiality Affirmed: The Supreme Court began by acknowledging the fundamental principle that financial institutions, through commercial custom or contractual agreement (express or implied), owe a duty of confidentiality to their customers regarding their transaction information and other personal or financial data obtained in the course of their dealings. They are not permitted to arbitrarily disclose such customer information to external parties.

- Confidentiality Duty is Owed to the Customer: The Court emphasized that this duty of confidentiality is primarily an obligation owed by the financial institution to its individual customer.

- When the Customer Lacks a Legitimate Interest in the Bank's Secrecy Against a Specific Litigant: This was the pivotal part of the Court's reasoning. If the customer whose information is being sought by a court order (in this case, B) is themselves a party to the main lawsuit for which the information is relevant, and if that customer (B) would be legally obligated to disclose that same information if they personally possessed the documents containing it (i.e., the documents are not otherwise privileged for B under the general exemptions for document production in CCP Article 220, Paragraph 4), then that customer (B) does not possess a legitimate interest that warrants protection through the bank's (Y's) assertion of its confidentiality duty against the other parties in that specific litigation. In essence, the customer cannot use the bank's confidentiality duty as a shield to withhold information they would otherwise have to produce themselves if it were in their direct possession.

- Bank's Disclosure Not a Breach of Duty in Such Specific Litigation Contexts: Consequently, if the customer (B) has no such legitimate interest in preventing disclosure within that particular lawsuit, the financial institution's disclosure of that customer's information, pursuant to a valid court order in that litigation, does not constitute a breach of its duty of confidentiality owed to that customer in the context of that lawsuit.

- Not a "Professional Secret" of the Bank (Unless the Bank Has Its Own Independent Interest): Therefore, the financial institution cannot refuse to produce the customer's information by claiming "professional secret" based on its duty to that customer under these circumstances. The information, in this scenario, is not protected as a professional secret under CCP Article 197, Paragraph 1, Item 3, unless the financial institution can demonstrate that it has its own, distinct, and legitimate proprietary interest in keeping that specific information secret, which would qualify as the bank's own professional secret (e.g., internal credit scoring methodologies, proprietary risk assessment data, trade secrets related to its operations, or confidential information about other unrelated customers if not easily severable).

- Application to B's Transaction Records Held by Y Credit Union:

- The requested Records contained B's transaction history with Y Credit Union.

- The Supreme Court found that Y Credit Union itself did not possess any independent proprietary interest in keeping B's basic transaction data secret that would qualify as Y's own professional secret warranting protection. Its refusal was based solely on its duty of confidentiality to its customer, B.

- B was a party (defendant) in the main inheritance lawsuit. If B personally held these transaction records, B would generally be obligated to produce them under CCP Article 220, as they would not typically fall under the exemptions like documents prepared exclusively for the holder's own use (Art. 220(4)(d)) in the context of an inheritance dispute about fund origins.

- Therefore, B had no legitimate interest in Y Credit Union withholding these specific records from disclosure in this particular litigation to which B was a party.

- The Court concluded that Y Credit Union's disclosure of the Records in this lawsuit would not constitute a breach of its duty of confidentiality owed to B.

- As a result, the Records were not documents containing information protected as a professional secret under CCP Article 197, Paragraph 1, Item 3, and Y Credit Union could not refuse to produce them on that ground.

The Supreme Court therefore quashed the High Court's decision and upheld the initial order compelling Y Credit Union to produce B's transaction records.

Analyzing the Decision: Balancing Confidentiality, Truth-Seeking, and Procedural Fairness

The Supreme Court's 2007 decision provides crucial clarification on the scope of "professional secrecy" for financial institutions in Japan:

- Clarifying the Basis of "Professional Secret" for Banks: The ruling shifts the primary focus from the bank's general business interest in maintaining overall customer trust to the specific, protectable interest of the customer whose data is at issue in the litigation. If that customer, being a party to the suit, would have to disclose the information anyway, the bank cannot use "confidentiality owed to that customer" as a reason to withhold it from the court.

- Bank's Own Secrets vs. Secrets Held for the Customer: The judgment implicitly distinguishes between information that constitutes the bank's own proprietary professional secret (which might still be protected) and information that is primarily the customer's data, which the bank holds under a more general duty of confidence. Basic transaction histories of a customer who is a litigant generally fall into the latter category when sought for that litigation.

- Procedural Fairness Concerns: As pointed out by legal commentators, a potential procedural issue arises: in a document production dispute between one litigant (X) and a third-party document holder (like Y Credit Union) concerning the information of another litigant (B), B themselves might not be a formal party to the document production motion itself. This could limit B's direct ability to argue against the disclosure of their information, even if they believe they have legitimate grounds for privacy beyond what the bank might assert as "professional secret." The court handling the motion would need to be mindful of protecting B's legitimate privacy interests where applicable.

- Scope and Impact: This ruling has broader implications for any situation where a third-party entity holds documents relevant to litigation between others, and one of the litigants is the "owner" or subject of the information contained in those documents. It reinforces the principle that duties of confidentiality owed to a party litigant do not generally shield relevant evidence from that same litigation if the party themselves would be obliged to produce it.

Justice Tahara's Concurring Opinion:

It's worth noting that Justice Mutsuo Tahara, in a detailed concurring opinion, further elaborated on the nature of customer information held by financial institutions. He classified different types of information (e.g., basic transaction data, financial statements provided by the customer, internal credit analyses, third-party credit reports) and discussed how the bank's duty of confidentiality and the applicability of "professional secret" might vary depending on the information's source and nature. He also touched upon scenarios where a bank might have a contractual obligation to its customer to assert professional secrecy on their behalf, for instance, if the customer has a valid legal ground to refuse disclosure that the bank is aware of.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's December 2007 decision strikes a balance between a financial institution's important duty of confidentiality to its customers and the overriding need for courts to access relevant evidence in the pursuit of truth and justice in civil litigation. It clarifies that a bank generally cannot invoke "professional secret" to shield a customer's transaction records when that customer is a party to the lawsuit and would themselves be obligated to produce such records. The ruling emphasizes that the primary protectable interest in such scenarios is that of the customer, and if that interest does not prevent disclosure by the customer themselves within the litigation, it generally cannot be used by the bank to resist a court order for production, unless the bank can demonstrate a distinct, independent proprietary interest in the secrecy of the information.