Bank Directors Under Scrutiny: A Japanese Supreme Court Case on Risky Lending and the Duty of Care

Case: Action for Damages

Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench, Judgment of January 28, 2008

Case Number: (Ju) No. 1440 of 2005

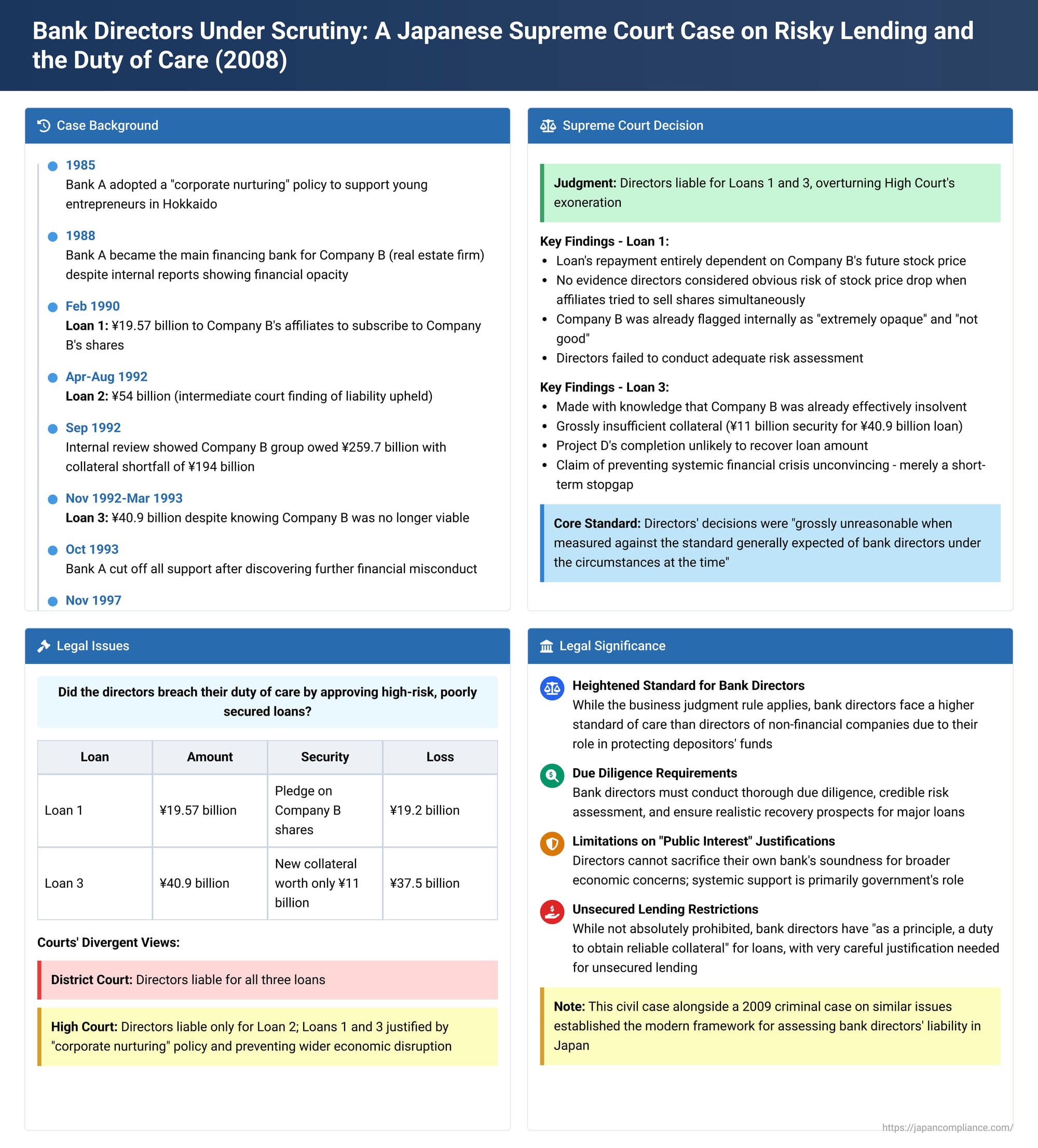

The collapse of Japan's "bubble economy" in the early 1990s led to a surge in non-performing loans and the failure of several financial institutions. In its wake, numerous lawsuits were filed seeking to hold bank directors personally liable for decisions that contributed to these losses. A landmark Supreme Court decision on January 28, 2008, provided crucial insights into the standards of duty of care and loyalty expected of bank directors, particularly concerning large and risky lending decisions. The Court found former directors of a failed bank liable for significant losses stemming from loans deemed "grossly unreasonable."

A Bank's Bet on a Risky Venture: Facts of the Case

The case involved Bank A, a regional bank based in Hokkaido. Around 1985, Bank A adopted a "corporate nurturing" policy, aiming to support and develop businesses run by young entrepreneurs in the region. One such enterprise was Company B, a real estate firm led by an individual named C. Despite some internal Bank A reports indicating that Company B's financial situation was opaque, Bank A's top management, after requesting (among other things) the disclosure of financial statements from Company B's subsidiaries, agreed to become its main financing bank.

In 1988, Company B embarked on an ambitious venture known as "Project D" – the construction and operation of a members-only luxury resort centered around a hotel. Bank A committed to financially supporting this project.

The lawsuit, brought by X (a debt collection agency that had acquired claims from the subsequently failed Bank A), focused on three large loans made by Bank A to Company B or its affiliates. The Supreme Court's judgment specifically re-evaluated and found liability for two of these:

Loan 1 (February 1990): 19.57 billion yen

- Purpose: This loan was provided to twelve affiliates of Company B. The funds were to be used by these affiliates to subscribe to a new third-party allotment of shares being issued by Company B itself. Company B planned this share issuance to raise capital for a potential listing on the Tokyo Stock Exchange and for project funding.

- Approval & Justification: Bank A's investment committee, which included the defendant directors, approved this substantial loan. The rationale presented at the time included Company B's rapid growth in sales and profits, its then-high stock price (20,500 yen as of January 1990), a belief that Company B's significant landholdings in Sapporo were unlikely to decrease in value, confidence that Bank A's guidance could prevent any deterioration in Company B's performance, and the strategic view that supporting C, seen as a leading young entrepreneur, would expand Bank A's business opportunities in the region.

- Security & Repayment Plan: Repayment of Loan 1 was anticipated three years later, from the proceeds of selling the shares that the affiliates had subscribed to using the loan. The primary security for the loan was a pledge on these subscribed Company B shares. Additionally, C provided a personal guarantee, though most of C's personal assets consisted of his own shares in Company B.

- Outcome: Company B's stock price did initially rise, peaking at 39,000 yen in July 1990. However, it began a steep decline thereafter. When Bank A later urged the borrowing affiliates to sell their pledged shares to start repaying the loan, C resisted, fearing that a large-scale sale would cause the stock price to crash further. By February 1992, the value of the pledged shares had fallen below the outstanding loan amount. Ultimately, approximately 19.2 billion yen of Loan 1 became unrecoverable.

(Loan 2 (April-August 1992): 54 billion yen)

While the High Court had found certain directors liable for this loan, and the Supreme Court did not overturn that specific part, the Supreme Court's new findings of liability focused on Loans 1 and 3. Loan 2 also resulted in substantial unrecoverable losses (approximately 30.9 billion yen).

Loan 3 (November 1992 - March 1993): 40.9 billion yen

- Context: By September 1992, the situation had become dire. An internal review at Bank A revealed that the Company B group owed Bank A and its affiliates a staggering 259.7 billion yen, with a collateral shortfall estimated at 194 billion yen based on current market values. Sales of memberships for Project D had stalled, cancellations were rising, and it was discovered that Company B had improperly diverted about 15.3 billion yen from these membership sales proceeds. Bank A's own assessment was that Company B was no longer a viable entity.

- Approval & Justification: Despite this bleak outlook, Bank A's management committee, including defendant directors Y1 and Y3, approved Loan 3 in October 1992. The stated justifications were multi-faceted: Bank A was already deeply financially committed to Project D and felt a responsibility to see it through to completion; as a leading bank in Hokkaido, it believed it needed to prevent a chain reaction of bankruptcies among local businesses connected to Company B; and there were fears that E Credit Union, which had lent 36.8 billion yen to the Company B group, might collapse and require a bailout from Bank A. Loan 3 was thus framed as providing the minimum necessary funds to keep Company B operating until June 1993, the planned opening date for Project D's hotel. Alongside this loan, Bank A also planned to recover other funds by having its affiliates purchase some of Company B's properties, securing additional collateral, and liquidating some of B group's overseas assets.

- Security: New collateral was taken for Loan 3, but its effective value was only around 11 billion yen. Formalizing some previously unregistered security interests added about 5.3 billion yen more. This total was far short of the 40.9 billion yen advanced.

- Outcome: The Project D hotel did open in June 1993 but consistently operated at a loss. In October 1993, Bank A finally cut off all support to Company B after discovering further financial misconduct by C. Company B, while technically still existing, became insolvent. Approximately 37.5 billion yen of Loan 3 became unrecoverable. Bank A itself ultimately failed in November 1997.

The Legal Battle: Were the Lending Decisions a Breach of Duty?

The plaintiff, X (the debt collection agency), sued the former directors of Bank A (Y1, Y2, Y3, Y4), alleging that these lending decisions, particularly Loans 1 and 3, constituted a breach of their duties of loyalty and care owed to the bank. This liability was claimed under Article 266, Paragraph 1, Item 5 of the then-Commercial Code (the substance of which is now found in Article 423, Paragraph 1 of the Companies Act).

The court of first instance found the defendant directors liable for all three loans. However, the High Court took a different view. It upheld liability only for Loan 2. For Loan 1, the High Court considered it part of Bank A's "corporate nurturing" policy and noted that the financing method (lending against newly issued shares of the supported company) was an accepted practice at the time. For Loan 3, the High Court accepted the justifications that it was aimed at preventing wider economic disruption, completing Project D, and maintaining Bank A's reputation, deeming these objectives not unreasonable even if Company B itself was no longer viable. The plaintiff, X, appealed the High Court's exoneration of the directors concerning Loans 1 and 3.

The Supreme Court's Verdict: Holding Directors Accountable for Loans 1 & 3

The Supreme Court overturned the High Court's decision regarding Loans 1 and 3. It found the defendant directors liable for the losses arising from these two loans as well, effectively reinstating the first instance court's findings on these points.

Reasoning of the Apex Court: "Grossly Unreasonable" Lending

The Supreme Court meticulously analyzed the circumstances surrounding Loans 1 and 3, concluding that the directors' decisions were "grossly unreasonable when measured against the standard generally expected of bank directors under the circumstances at the time," thus constituting a breach of their duties.

For Loan 1 (Share Subscription Financing):

- Extreme and Undue Risk: The Court highlighted that the recovery of this very large loan (19.57 billion yen) was entirely dependent on the future business performance and stock price of Company B. Given that stock values are inherently more volatile than, for example, real estate collateral, and that the borrowers were all affiliates of Company B (meaning their fate was tied to Company B's), making such a huge loan reliant solely on these factors demanded "especially careful consideration."

- Insufficient Diligence and Risk Assessment: The Court found a critical failure in due diligence. It should have been "easily foreseeable" that if all the borrowing affiliates attempted to sell their large blocks of pledged Company B shares around the loan's maturity date to generate repayment funds, this mass sale would likely cause the stock price to plummet, rendering the collateral insufficient. Yet, the Supreme Court noted there was "no evidence of deliberation or study" (kentō) concerning this significant risk or any potential strategies to mitigate it.

- Questionable Choice of "Nurturing" Candidate: While acknowledging that a bank supporting promising enterprises, even without strong real property collateral, is not per se unreasonable (if based on thorough due diligence and a rational judgment of growth potential), the Court pointed to Bank A's own prior internal investigations from 1985 and 1988. These reports had already flagged Company B's financial condition as "extremely opaque" and "not good" due to excessive borrowing. In light of this pre-existing negative information, the Court found Bank A's very decision to select Company B as a target for its "corporate nurturing" policy to be questionable. Even if Company B was chosen, the Court suggested that more prudent, project-specific financing choices could have been made, rather than embarking on such a high-risk share-financing scheme. The decision to provide Loan 1 under these circumstances was deemed to lack rationality.

For Loan 3 (Bailout Loan to an Effectively Insolvent Company):

- Known Unrecoverability: The Court emphasized that Loan 3 was made with the understanding that Company B was already on the brink of collapse and no longer considered viable. It was clear from the outset that the vast majority of this 40.9 billion yen loan would not be recovered from Company B itself. The new collateral taken was grossly insufficient.

- Flawed Justification – Completion of Project D: While Bank A had already sunk considerable funds into Project D, the Court found no credible basis to believe that completing Project D would lead to the recovery of amounts commensurate with Loan 3. By the time Loan 3 was approved, there were already severe doubts about Project D's own financial viability (stagnant membership sales, misappropriation of funds by Company B, and reports indicating further massive funding needs for completion). The internal bank reports suggesting a significant increase in collateral value from Project D's completion or its future profitability were dismissed by the Court as clearly not based on sufficient data or reasonable analysis.

- Flawed Justification – Systemic Risk Mitigation: The directors had also argued that Loan 3 was necessary to prevent a chain of bankruptcies among businesses linked to Company B and to avoid the potential failure of E Credit Union, which had also heavily lent to the Company B group. The Supreme Court found this rationale unconvincing. Loan 3 was merely intended to keep Company B afloat for a few additional months; it was not a genuine restructuring effort aimed at restoring Company B to health. The Court reasoned that such a short-term lifeline was unlikely to genuinely avert the feared wider economic consequences or the potential failure of E Credit Union. Therefore, these systemic risk concerns did not provide a rational basis for approving Loan 3.

Analysis and Implications: Heightened Standards for Bank Directors

This 2008 Supreme Court decision is a critical piece of jurisprudence regarding the duties of bank directors in Japan.

- The Business Judgment Rule and Bank Directors:

The Supreme Court's language, particularly its use of the "grossly unreasonable" (ichijirushiku fugōri) standard, is consistent with the application of the business judgment rule. This rule generally protects directors from liability for honest, informed decisions that turn out badly, provided the decision wasn't irrational.

However, the context of banking is special. A subsequent Supreme Court criminal case in November 2009 (dealing with special breach of trust by bank directors) explicitly addressed this. It stated that while the business judgment rule can apply to bank directors, the standard of care expected of them is inherently higher than that for directors of non-financial companies. This is due to several factors: banking is a licensed industry that operates using depositors' funds; bank failures can have severe systemic consequences for the wider economy; and bank directors are expected to possess specialized knowledge and experience in financial risk management and lending. Consequently, the "room for application" of the business judgment rule, in a way that might excuse a decision, is more limited for bank directors. The 2008 civil judgment in the Bank A case, while not elaborating on this theory to the same extent, appears to implicitly apply this heightened level of scrutiny. Abstract discussions of a "higher" or "lower" duty are often less helpful than focusing on the concrete expectations placed on directors in specific industries. - Specific Breaches Identified by the Court:

The Court pinpointed clear failures in the directors' decision-making:- For Loan 1: A failure in fundamental risk assessment – particularly the over-reliance on the volatile stock of a single, already troubled corporate group as the primary source of repayment for a massive loan, and the neglect of the obvious market risk associated with the potential mass sale of that stock as collateral. Furthermore, the initial decision to heavily back Company B under the "corporate nurturing" policy was itself flawed given the negative internal information already available about Company B.

- For Loan 3: The decision to extend further significant credit to a company already acknowledged internally as non-viable, without a credible restructuring plan or a realistic prospect of recovering the new funds, was deemed grossly unreasonable. The justifications offered (such as the value increase from completing Project D or mitigating systemic financial risk) were found to be based on inadequate analysis and unrealistic expectations.

- Lending Without "Reliable Real Property Collateral":

Interestingly, in its reasoning for Loan 1, the Supreme Court included a general statement: "In general, it is not to be denied as an unreasonable decision without exception for a bank, after sufficiently grasping information such as the financial condition, business content, and managerial qualities of a specific enterprise, and having rationally judged that there is growth potential, to proactively provide financing to support its management financially, even without reliable real property collateral." This suggests that unsecured or under-collateralized lending to promising growth companies is not per se a breach of duty.

However, the aforementioned 2009 Supreme Court criminal case stated more forcefully that bank directors, in conducting lending operations, have a duty to ensure collectability and, as a principle, should obtain reliable collateral and take other appropriate measures to secure the loan. While this doesn't absolutely forbid unsecured lending, it emphasizes a strong preference for security. The 2009 criminal case also outlined stringent conditions under which additional unsecured or under-collateralized lending to an already distressed company (for restructuring purposes) might be permissible, including an objective and detailed restructuring plan and a strong financial position of the lending bank itself, coupled with formal internal approval processes. There appears to be a tension here that requires banks to very carefully justify lending that deviates from the principle of seeking robust collateral, especially to companies that are not demonstrably low-risk and high-growth. - "Public Interest" Arguments vs. Bank Soundness:

The justification for Loan 3 partly rested on the idea of preventing wider economic damage (chain bankruptcies, failure of another financial institution). While the Banking Act (Article 1) does acknowledge the public nature of banking, the Supreme Court's approach suggests that this public role must be exercised on the foundation of the bank's own financial soundness and prudent management. Directors cannot typically justify decisions that recklessly endanger their own institution under the primary guise of protecting the broader regional economy. Such systemic support functions are more appropriately the domain of government or central bank actions, especially if they require a bank to act against its own core financial interests. This was echoed in another 2009 Supreme Court civil case where bank directors were found liable for making further loans to a failing company at a prefecture's request when the situation was clearly beyond recovery.

This 2008 Supreme Court decision, especially when read alongside the 2009 criminal ruling, provides a crucial framework for assessing the liability of bank directors in Japan. It underscores that while business judgment is respected, bank directors operate under a heightened standard of care. Their decisions, particularly in high-stakes lending, must be based on thorough due diligence, credible risk assessment, realistic recovery prospects, and a primary focus on the soundness of their own institution. Failure to meet these standards, resulting in "grossly unreasonable" decisions, can lead to significant personal liability.