Balcony Alterations and Condominium Living: A Deep Dive into a 1975 Japanese Supreme Court Ruling

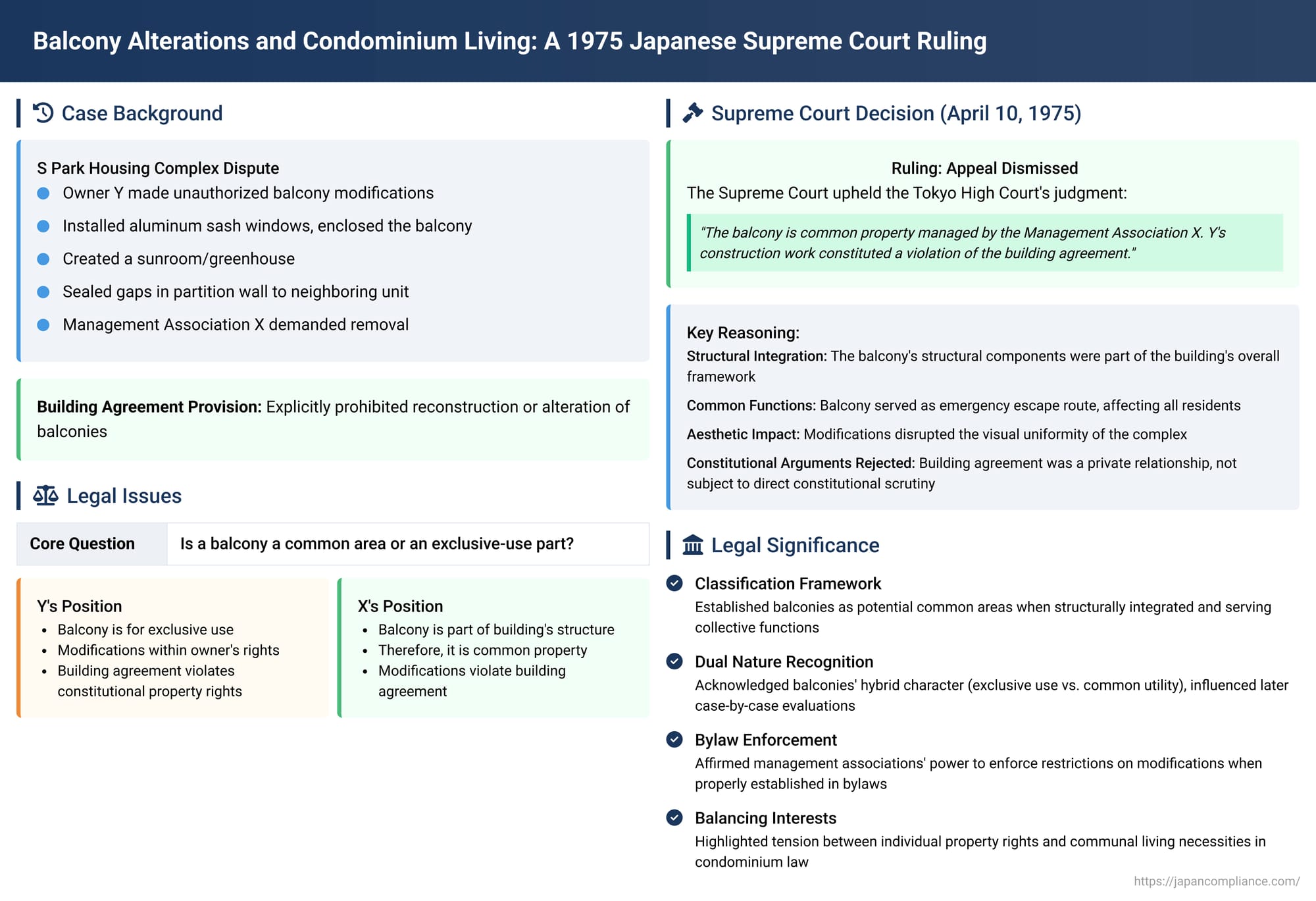

Tokyo, Japan - A seminal decision by the Supreme Court of Japan, delivered on April 10, 1975, continues to offer crucial insights into the complexities of condominium law, particularly concerning the classification of balconies and the extent to which residents can alter them. This case, involving a dispute over unauthorized balcony modifications, delves into the fundamental definitions of exclusive-use parts versus common areas within a condominium structure, a distinction that carries significant weight for management associations and unit owners alike.

The Genesis of the Dispute: A Balcony Transformed

The case centered around a housing complex, the S Park housing complex, originally developed by a public housing corporation. All purchasers of units in this complex were members of a Management Association, X. This association, X (the Appellee), had established a building agreement—understood to function as bylaws under Japan's Condominium Ownership Act—which explicitly prohibited members from reconstructing or altering the balconies of their residential units.

Despite this prohibition, a unit owner, Y (the Appellant), undertook significant modifications to the balcony of his unit. Y utilized the existing southern railing of the balcony to attach a wooden and aluminum sash frame, fitting it with aluminum sash glass doors to create windows. This new construction, integrated with the original railing, effectively formed an exterior wall, transforming the open balcony into an enclosed space. Furthermore, Y sealed the gaps on either side of the partition separating his balcony from the neighboring unit's balcony with plywood and installed an awning window in the upper part. Through these alterations, the balcony was converted into an independent room, shielded from the outside elements, which Y then used as a sunroom or greenhouse.

The Management Association, X, initiated legal action, demanding that Y remove the additions and restore the balcony to its original condition, citing the clear violation of the building agreement.

The Lower Court's Stance: Balcony as Common Property

The Tokyo High Court, serving as the lower court of appeal, ruled in favor of the Management Association, X. Its decision was grounded on several key findings. Firstly, the court interpreted X's association rules (also considered equivalent to bylaws under the Condominium Ownership Act) as stipulating that the structural frame of the condominium building was common property managed by X. Crucially, it was undisputed by the parties that the structural components of the balcony in question were part of this overall building frame. Therefore, the High Court concluded that Y's balcony was, by definition, common property under the management of X.

The court found that Y's modifications inherently changed the balcony's original form and function, thereby constituting a direct breach of the building agreement's prohibition against such alterations. Beyond the letter of the agreement, the court also considered its underlying purpose. The prohibition on balcony modifications was intended to maintain the aesthetic uniformity of the entire housing complex and, critically, to preserve the functionality of balconies as emergency escape routes. The balconies in the complex were designed to be interconnected, with partitions between them that could be easily broken through in an emergency to allow passage to neighboring units. Y's enclosure of his balcony and reinforcement of the partition directly conflicted with these essential objectives. Consequently, the High Court ordered Y to remove the unauthorized structures. Y subsequently appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Affirmation (April 10, 1975)

The Supreme Court upheld the Tokyo High Court's judgment, dismissing Y's appeal. The highest court found the lower court's reasoning to be sound and justifiable. It affirmed the determination that the balcony was common property managed by the Management Association, X. It also concurred that Y's construction work constituted a violation of the building agreement, which prohibited balcony alterations, and therefore, Y was obligated to dismantle the additions and restore the balcony to its original state.

Y had also raised constitutional arguments in his appeal, asserting that the building agreement violated Articles 13 (right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness) and 29 (property rights) of the Constitution of Japan. The Supreme Court addressed this by referencing its established precedent that these constitutional provisions do not directly apply to relationships between private parties. The Court noted that the building agreement and association rules were adopted unanimously by the attendees (including Y) at X's inaugural general meeting and subsequently formalized through written consent from all members of X. Thus, the legal relationship between X and its members, governed by these agreements, was deemed a private one, precluding the direct application of the cited constitutional articles. The Court further stated that the prohibition on balcony alterations within the building agreement was not contrary to public order and morals.

Unpacking the Core Issue: Is a Balcony Exclusive or Common Property?

The Supreme Court's ruling, by affirming the lower court, implicitly categorized the balcony as a "statutory common area" as defined by Japan's Condominium Ownership Act (Article 4, Paragraph 1), rather than an "exclusive-use part" (Article 2, Paragraph 3). This classification is pivotal and warrants deeper exploration.

Generally, in condominium law, an "exclusive-use part" refers to a section of a building intended for the exclusive ownership and use of an individual unit owner (e.g., the interior of an apartment unit). A "common area," conversely, is intended for the use of all or a portion of the unit owners (e.g., hallways, elevators, the building's structural framework).

The lower court, and by extension the Supreme Court, reasoned that because the structural components of the balcony (its floor, railings, etc.) were integral to the building's overall structural frame—which is almost universally considered a common area—the balcony itself qualified as a common area.

However, a nuanced perspective considers that a balcony comprises not only its physical structure but also the "balcony space" – the area enclosed or defined by these structural elements. If Y's alterations were viewed as primarily affecting this "balcony space," the legal character of this space itself (whether exclusive or common) would need careful determination. The judgment did not delve deeply into this specific distinction, a point often discussed in subsequent legal commentaries.

The Dual Character of "Balcony Space"

"Balcony space" often presents a fascinating legal puzzle due to its seemingly contradictory characteristics, simultaneously exhibiting features of both exclusive use and common utility.

- Arguments for Exclusive-Use Nature:

- Connection and Dedication: A balcony is typically directly connected to an individual residential unit and is, in everyday practice, used exclusively by the occupants of that unit. This dedicated usage can support the notion of "functional independence," a key criterion for classifying a part as exclusive. The owner of the adjoining unit often considers the balcony an extension of their living space.

- Arguments for Common Area Nature:

- Emergency Egress: As highlighted in the S Park housing complex case, balconies can serve as vital emergency escape routes for multiple residents, especially in interconnected designs. If a balcony forms part of a planned evacuation path, its common utility is undeniable.

- Building Aesthetics and Uniformity: Balconies significantly contribute to the overall external appearance of a condominium building. Alterations to individual balconies can disrupt the architectural harmony and aesthetic integrity of the entire structure, affecting the collective interest of all owners.

- Structural Integrity and Maintenance: Modifications to balconies, even if seemingly superficial, can potentially impact the building's structural integrity or complicate maintenance efforts, which are typically managed as common responsibilities.

Judicial Trends in Classifying Balconies

Given this dual nature, courts often engage in a fact-specific inquiry, weighing the elements of exclusive use against those of common utility for the specific balcony in question. The outcome is not predetermined but rather depends on which characteristics are more dominant in a given case.

- Decisions Favoring "Exclusive-Use Part":

- Some court decisions have leaned towards classifying a balcony as an exclusive-use part (or a part subject to exclusive-use rights, even if structurally common) when its role as an emergency route is negligible or non-existent according to its design or the building's fire safety plans.

- If a balcony is not readily visible from the exterior and thus has minimal impact on the building's overall aesthetic, this might also support an exclusive-use characterization for certain regulatory purposes. One such case involved a balcony that was not an emergency escape route and was not visible from outside theマンション (mansion - Japanese condominium), leading to its classification as an exclusive-use part.

- However, even if deemed an exclusive-use part, restrictions on its alteration can still be imposed through bylaws if those alterations negatively affect common interests.

- Decisions Favoring "Statutory Common Area":

- Conversely, where balconies are structurally integral to the building (e.g., part of the main framework) and also play a clear role in emergency evacuations or significantly influence the building's external appearance and maintenance, courts are more likely to classify them as statutory common areas.

- The S Park housing complex case aligns with this line of reasoning, emphasizing both the structural integration and the common utility (emergency egress and aesthetics).

- Another ruling highlighted that balconies in multi-story residential buildings often fulfill a crucial role as emergency escape routes and are closely linked to the building's overall visual appeal, thereby justifying their regulation as common areas.

Legal scholarship largely supports this nuanced approach, suggesting that the classification of a balcony space should depend on its specific form and function. For example, a balcony that is entirely self-contained, serving only one unit and completely isolated from others with no possibility of passage, might more readily be seen as having strong "exclusive-use" characteristics. In contrast, a balcony designed with breakable partitions for emergency passage, like those in the S Park complex, clearly possesses a strong "common use" element, pointing towards classification as a statutory common area.

The Impact of Classification: Why Does It Matter?

The determination of whether a balcony (or its space) is an exclusive-use part or a statutory common area has significant legal ramifications, particularly concerning its alteration and use.

- If Classified as a Statutory Common Area:

- The balcony is subject to the provisions of the Condominium Ownership Act pertaining to common areas (Articles 13 and following).

- Its management, use, and any modifications fall under the purview of the management association and are governed by the association's bylaws (referred to as the "building agreement" in the S Park case).

- Individual unit owners generally cannot unilaterally alter common areas without proper authorization as stipulated in the bylaws or relevant legislation, which often requires a collective decision-making process.

- If Classified as an Exclusive-Use Part:

- While the owner has more autonomy, their rights are not absolute. They are still bound by general obligations under the Condominium Ownership Act not to engage in acts detrimental to the common interest or the interests of other owners (e.g., Article 6, Articles 57 and following).

- Crucially, the Condominium Ownership Act (Article 30, Paragraph 1) allows matters concerning the use and management of exclusive-use parts to also be stipulated in the bylaws, provided such stipulations are necessary to coordinate the mutual interests of the unit owners. This means that even if a balcony space is considered an exclusive-use part, the bylaws can still impose restrictions on its alteration to protect common interests such as:

- Preservation of the building's structural integrity.

- Ensuring the functionality of emergency escape routes.

- Maintaining the aesthetic harmony of the building.

- Preventing disturbances to other residents.

The Subtle Distinction in Regulatory Scope

While bylaws can regulate both common areas and exclusive-use parts, a key difference lies in the potential scope and intensity of that regulation.

- For common areas, bylaws can broadly define rules for management and use.

- For exclusive-use parts, the principle is that they are primarily for the owner's free use and disposition. Therefore, bylaw restrictions on exclusive-use parts are generally permissible only to the extent necessary to adjust and harmonize the interests of all co-owners. This implies that bylaws seeking to regulate exclusive-use parts might face a higher threshold of justification compared to those governing common areas.

This ultimately leads to the broader legal question: To what extent can bylaws legitimately limit the property rights of an individual unit owner over a part of the building deemed to be for their exclusive use? The S Park housing complex case, while classifying the balcony as common property, touches upon this underlying tension inherent in condominium living – the balance between individual property rights and the collective welfare of the community.

Concluding Reflections on the S Park Balcony Case

The Supreme Court's 1975 decision in the S Park housing complex balcony dispute remains a significant reference point in Japanese condominium law. It underscores several enduring principles:

- Balancing Interests: Condominium living inherently requires a balance between the desires of individual unit owners and the collective interests of the entire community. This case demonstrates that actions taken within what an owner might perceive as their private domain (like a balcony) can have broader implications requiring regulation.

- Clarity in Bylaws: The case highlights the critical importance of clear, comprehensive, and legally sound building agreements or bylaws. The explicit prohibition on balcony alterations in the S Park housing complex's agreement was a cornerstone of the Management Association's successful claim.

- The Evolving Understanding of Balconies: While the S Park decision leaned on the structural integration of the balcony frame to classify it as common property, subsequent legal discourse and jurisprudence have increasingly recognized the nuanced, dual character of balcony spaces. This calls for a careful, case-by-case analysis of a balcony's design, function, and context.

- Purpose of Restrictions: The underlying reasons for restrictions—such as ensuring safety (emergency egress) and maintaining community value (aesthetics)—are important justifications for limiting an owner's ability to alter certain features.

The S Park case serves as a lasting reminder of the unique legal environment of condominiums, where shared ownership and communal living necessitate a framework of rules that can sometimes limit individual autonomy for the greater good of the community. The precise line between an exclusive-use part and a common area, especially for hybrid elements like balconies, will continue to be a subject of careful legal interpretation, emphasizing the need for meticulous drafting of condominium bylaws and a thoughtful approach to their enforcement.