Balancing Treatment and Liberty: Japan's Supreme Court Upholds Constitutionality of the Medical Treatment and Supervision Act

Date of Decision: December 18, 2017, Supreme Court of Japan (Third Petty Bench)

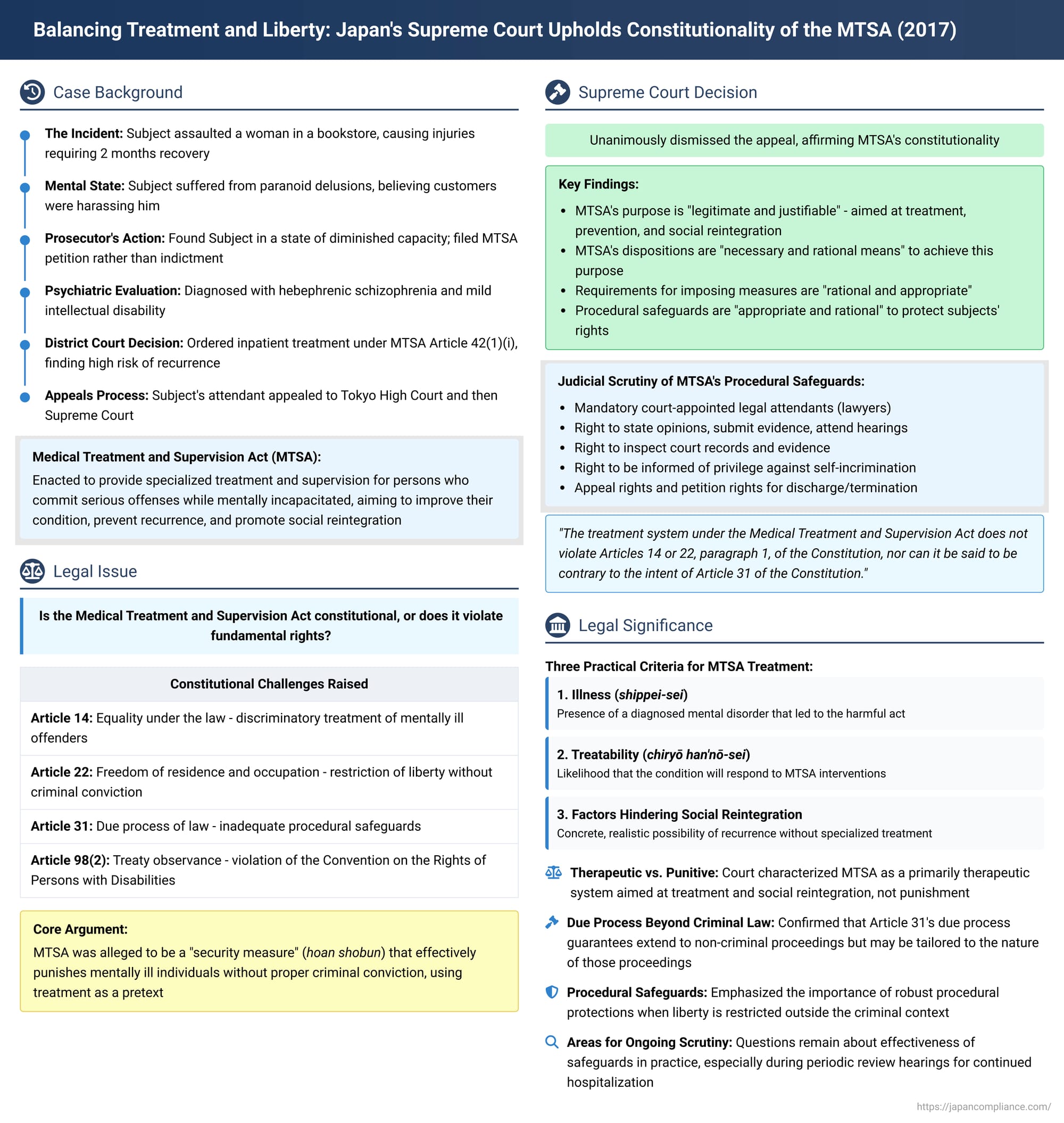

Navigating the intersection of mental illness, public safety, and individual rights presents profound challenges for any legal system. In Japan, the "Act for Medical Treatment and Supervision of Persons Who Have Caused Serious Harm to Others in a State of Insanity or Diminished Capacity" (commonly known as the 医療観察法 - Iryō Kansatsu Hō, or Medical Treatment and Supervision Act, MTSA) provides a specialized framework for individuals who commit serious offenses while mentally incapacitated. On December 18, 2017, the Supreme Court of Japan issued a landmark decision affirming the overall constitutionality of this Act, addressing concerns about discrimination, due process, and deprivation of liberty.

The Case: An Assault, Mental Incapacity, and the MTSA Pathway

The case involved an individual (referred to as "the Subject") who, in September 2016, assaulted a woman in a bookstore by suddenly bumping into her, causing her to fall and sustain a sacral fracture that required approximately two months for recovery. It was found that for several years prior, the Subject had been experiencing paranoid delusions, believing they were being pursued or watched by a "brainwashing group." At the scene of the incident, the Subject felt they were being followed and harassed by several customers, including the victim, for tens of minutes. Believing an attack was imminent due to these delusions, the Subject acted out in what they perceived as preemptive self-defense or retaliation.

The Yokohama District Public Prosecutor's Office, Odawara Branch, investigated the incident. It determined that the Subject was in a state of diminished capacity (shinshin kōjaku) at the time of the assault, primarily due to the strong influence of their delusional state. Consequently, in February 2017, the prosecutor chose not to indict the Subject for criminal charges of injury. Instead, invoking Article 33, paragraph 1 of the MTSA, the prosecutor filed a petition with the Yokohama District Court to initiate proceedings under the Act.

An expert psychiatric examination conducted during a court-ordered temporary hospitalization revealed that the Subject was suffering from hebephrenic schizophrenia and mild intellectual disability. While medication administered during this period led to some improvement, the Subject still lacked insight into their illness (byōshiki). There was a history of discontinuing treatment for other conditions like adjustment disorder. During the evaluation admission, there was an incident where the Subject hugged another female patient. The expert concluded that the Subject had a fragile ego, a high probability of losing emotional control under stress, and a significant risk of impulsive or emotional behavior leading to harm if adequate treatment was not maintained. A social circumstances report indicated that the Subject's mother was willing to assist with outpatient care but that cohabitation would be difficult.

Based on these reports and the results of a court hearing, the Yokohama District Court determined that there was a high, concrete, and realistic probability of the Subject committing similar harmful acts if their symptoms were to worsen without early and appropriate medical intervention. Finding that all statutory criteria for imposing inpatient treatment under the MTSA were met—namely, (1) the presence of a qualifying mental illness, (2) the treatability of the condition, and (3) the necessity of hospitalization to prevent recurrence and promote social reintegration—the District Court, on April 4, 2017, ordered that the Subject be hospitalized for medical treatment pursuant to Article 42, paragraph 1, item (i) of the MTSA.

The Subject's court-appointed attendant (a lawyer) appealed this decision to the Tokyo High Court, arguing that the MTSA itself violated several articles of the Japanese Constitution, including Article 14, paragraph 1 (equality under the law), Article 22, paragraph 1 (freedom of residence and occupation), and Article 31 (due process). The appeal also contested the District Court's factual findings regarding the Subject's illness, treatability, and factors hindering social reintegration, and further alleged violations of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD). On July 14, 2017, the Tokyo High Court dismissed this appeal.

The attendant then filed a further appeal (a special "re-appeal") with the Supreme Court. The core arguments were that the MTSA's legislative purpose was discriminatory and lacked rationality; that its dispositions and eligibility requirements were effectively "security measures" (hoan shobun – preventive measures that can resemble punishment if not carefully circumscribed) also lacking rationality; that its procedures were deficient in ensuring due process (citing non-public hearings and the lack of explicit advice on the right to silence); and that it contravened the CRPD, thereby violating Article 98, paragraph 2 of the Constitution (which mandates observance of treaties).

The Supreme Court's Ruling (December 18, 2017)

The Supreme Court unanimously dismissed the appeal, thereby affirming the constitutionality of the Medical Treatment and Supervision Act.

Legitimate Purpose of the MTSA:

The Court began by reiterating the stated purpose of the MTSA as defined in its Article 1, paragraph 1: "to provide continuous and appropriate medical care, as well as the observation and guidance necessary to secure such care, for persons who have committed serious harm to others while in a state of insanity or diminished capacity, thereby aiming to improve their medical condition, prevent the recurrence of similar acts, and promote their social reintegration." The Supreme Court explicitly found this legislative purpose to be "legitimate and justifiable."

Rationality of Dispositions and Requirements:

The Court then addressed the MTSA's provisions for inpatient (Article 42, paragraph 1, item (i)) or outpatient treatment (item (ii)). It held that such dispositions are "necessary and rational means for achieving the aforementioned [legitimate] purpose." Furthermore, the requirements for imposing these measures—primarily the need for MTSA treatment to improve the mental disorder, prevent recurrence of harmful acts, and facilitate social reintegration—were also deemed "rational and appropriate" and consistent with the Act's purpose. The legislative history of the MTSA, which saw an initial proposal focusing on "risk of re-offending" (akin to a security measure) being modified to "necessity of receiving medical treatment under this Act," supports the interpretation that the Act is primarily therapeutic rather than punitive.

Adequacy of Procedural Safeguards:

A significant portion of the Supreme Court's reasoning focused on the procedural protections afforded to individuals under the MTSA. The Court highlighted that:

- The MTSA proceedings are distinct from criminal procedures and employ an inquisitorial approach where the court actively investigates the facts (Article 24).

- Hearings are generally not open to the public, a measure intended to protect the privacy of the subject (Article 31, paragraph 3).

- Decisions are made by a specialized panel typically consisting of one judge and one lay mental health assessor (Article 11, paragraph 1).

- There is a system of mandatory court-appointed legal attendants (lawyers) for the subject (Articles 30 and 35).

- These attendants are granted various rights, including the right to state opinions and submit evidence (Article 25, paragraph 2), attend hearings (Article 31, paragraph 6), and inspect court records and evidence (Article 32, paragraph 2).

- In hearings concerning the initial disposition, the subject must be informed that they cannot be compelled to make statements against their will. The court is required to hear the opinions of both the subject and their attendant (Article 39, paragraph 3).

- The subject and their attendant have the right to appeal decisions (Article 64, paragraph 2) and to petition for discharge from inpatient treatment or termination of outpatient treatment (Articles 50 and 55).

Based on this comprehensive list, the Supreme Court concluded that "appropriate and rational procedures are established [within the MTSA] to swiftly implement necessary medical care for the subject, ensure the subject's privacy, and promote smooth social reintegration."

Due Process under Constitution Article 31:

The Court acknowledged that Article 31 of the Constitution, which guarantees due process of law, primarily pertains to criminal procedures. However, it stated that "it is not appropriate to judge that all non-criminal procedures are naturally outside the scope of the guarantee under said Article merely because they are not criminal procedures." The manner and extent of due process protection depend on the nature of the specific procedure in question. In the case of the MTSA, the Supreme Court found that "sufficient procedural guarantees appropriate to its nature are provided."

Overall Constitutionality:

Considering the MTSA's legitimate purpose, the necessity, rationality, and appropriateness of its dispositions and requirements, and the content of its procedural safeguards, the Supreme Court concluded that "the treatment system under the Medical Treatment and Supervision Act does not violate Articles 14 or 22, paragraph 1, of the Constitution, nor can it be said to be contrary to the intent of Article 31 of the Constitution." The Court cited two of its own precedents concerning due process in the context of administrative detention to support this view.

Discussion: Key Aspects of the MTSA System and Its Constitutional Scrutiny

The Supreme Court's decision provides a strong judicial endorsement of the MTSA. Several aspects are noteworthy:

- Therapeutic, Not Punitive: A core element underpinning the Court's finding of constitutionality is the characterization of the MTSA as a therapeutic system aimed at treatment and social reintegration, rather than a punitive one. This distinction was also highlighted by the High Court when it dismissed attempts to compare the average length of MTSA hospitalization (around 2.5 years, according to some commentaries) with criminal sentences for similar initial offenses, deeming such comparisons "misplaced."

- The Three Practical Criteria for MTSA Treatment: While the MTSA text speaks broadly of the "necessity of receiving medical treatment," in practice, judicial decisions and expert evaluations often rely on three key criteria:

- Illness (疾病性 - shippei-sei): The presence of a diagnosed mental disorder that led to the diminished capacity and the harmful act. This justifies intervention, partly on paternalistic grounds for the subject's own benefit.

- Treatability / Treatment Responsiveness (治療反応性 - chiryō han'nō-sei): The likelihood that the mental disorder will respond positively to the medical interventions available under the MTSA. This is crucial; if a condition is deemed untreatable by MTSA methods (e.g., certain irreversible conditions), then applying the MTSA might be inappropriate, and other legal frameworks (like the Mental Health and Welfare Act) might come into play. This treatability requirement helps distinguish the MTSA from purely preventative detention or "security measures."

- Factors Hindering Social Reintegration (Risk of Recurrence): This involves assessing the likelihood that, without the specialized treatment and supervision provided by the MTSA, the individual would commit similar harmful acts in the future. The High Court in this case clarified that this requires a "concrete and realistic possibility" of recurrence, not just a vague sense of dangerousness, thereby aiming to prevent discriminatory application based on prejudice against those with mental illness. In the Subject's case, traits like a fragile ego and poor impulse control were seen as symptoms of the illness requiring treatment, rather than inherent personality flaws deserving of incapacitation.

- Procedural Due Process in a Non-Criminal Context: The Supreme Court's affirmation that non-criminal proceedings impacting liberty also require due process, albeit tailored to the nature of those proceedings, is significant. The MTSA's inquisitorial system (where the court actively seeks facts), non-public hearings (balancing privacy with transparency concerns), and reliance on a specialized panel and a mandatory legal attendant are features deemed to meet this tailored due process standard. The attendant's role, in particular, is seen as a vital safeguard.

Persisting Concerns and Areas for Future Consideration

Despite the Supreme Court's comprehensive endorsement, legal commentators and human rights advocates continue to discuss certain aspects of the MTSA, particularly regarding the ongoing protection of rights once an individual is within the system:

- Effectiveness of Procedural Safeguards: While the MTSA lists numerous procedural rights, questions sometimes arise about their practical effectiveness, especially when the subject lacks insight into their illness or ability to fully participate in their own defense. The role of the attendant becomes even more critical in such situations.

- Review Hearings for Continued Hospitalization: A notable concern raised in legal commentary (though not a direct finding of the Supreme Court in this specific appeal) pertains to the procedural safeguards during periodic reviews of continued hospitalization (typically every six months under Articles 49 and 51). Some crucial protections applicable at the initial disposition hearing, such as the mandatory nature of the attendant's involvement (Article 35) and the necessity of holding a formal hearing where the subject's opinion is heard (Article 39), are not explicitly cross-referenced as mandatory for these review proceedings (see Article 53). This could potentially weaken the subject's ability to challenge continued confinement if decisions rely heavily on medical reports from the treating institution without robust adversarial scrutiny.

- The Broader Landscape of Involuntary Psychiatric Commitment: Japan has other legal mechanisms for involuntary psychiatric commitment (e.g., under the Mental Health and Welfare Act, for individuals at risk of harming themselves or others, or for medical protection with family consent). These systems also face ongoing scrutiny regarding due process and patient rights. Some argue for a more integrated and comprehensive review of all forms of involuntary psychiatric hospitalization to ensure consistent and robust human rights protections across the board.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court of Japan's December 18, 2017, decision represents a significant affirmation of the constitutionality of the Medical Treatment and Supervision Act. By underscoring the Act's legitimate therapeutic and public safety objectives, the rationality of its criteria for imposing treatment, and the adequacy of its procedural safeguards, the Court has solidified the MTSA's legal foundation. This ruling confirms that specialized systems designed to address the complex needs of individuals who commit serious harm while mentally incapacitated can be compatible with constitutional guarantees, provided they are well-purposed and procedurally fair. Nevertheless, ongoing vigilance and discussion, particularly concerning the practical application of rights during continued treatment and review phases, remain essential to ensure that this unique legal-medical framework operates in a manner that is both effective and consistently respectful of the fundamental human rights of those under its purview.