Balancing Transparency and Secrecy: Document Disclosure Rules for Japan's National University Corporations

Decision Date: December 19, 2013

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench

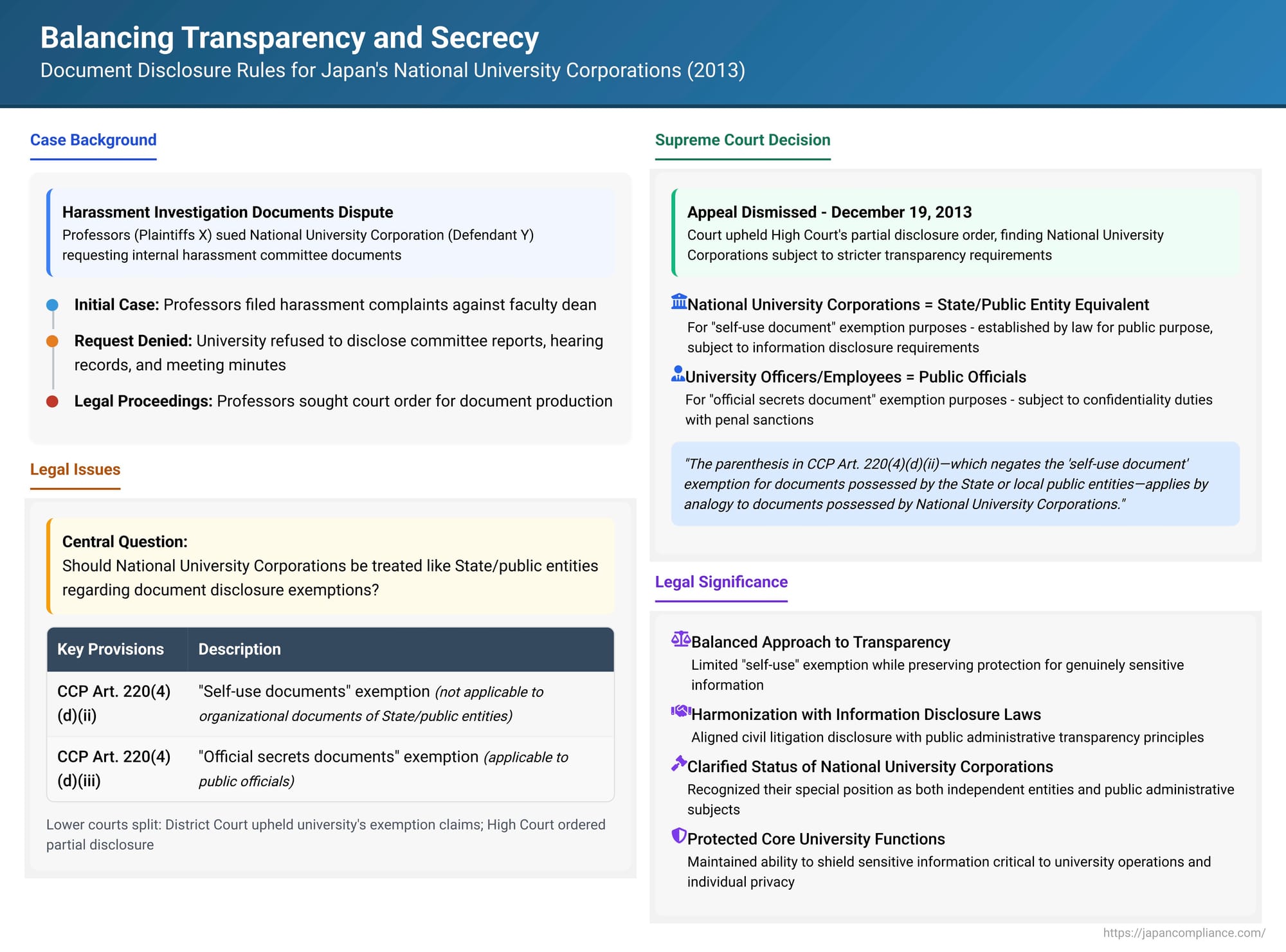

In an era of increasing demands for transparency from public institutions, a 2013 Japanese Supreme Court decision addressed a critical issue: To what extent must National University Corporations disclose internal documents during civil litigation? The case explored whether these entities, transformed from state organs into independent corporations in 2004, should be treated like the State or local public entities regarding document production rules, particularly concerning exemptions for "self-use documents" and "official secrets documents" under Japan's Code of Civil Procedure (CCP).

The Harassment Complaint and the Quest for Internal Documents

The case arose from a dispute within a university operated by Y, a National University Corporation. Several professors, X et al., filed harassment complaints with Y against their faculty dean and other university officials. They subsequently alleged that they suffered disadvantages due to improper operational methods and investigation procedures employed by Y's internal harassment committee. To substantiate these claims in their lawsuit against Y for a re-investigation and monetary damages, X et al. sought a court order compelling Y to produce several internal documents. These included the harassment committee's investigation report, records of hearings with individuals subject to the investigation, and minutes of the committee's meetings (collectively, "the Documents").

Y resisted the production order, arguing that the Documents were exempt under two provisions of Japan's Code of Civil Procedure (CCP) Article 220(4):

- CCP Art. 220(4)(d)(ii): This exempts "documents prepared exclusively for the use of the possessor" (commonly referred to as "self-use documents"). However, a crucial parenthesis within this sub-item states that this exemption does not apply to documents possessed by "the State or a local public entity" if they are "documents that public officials use organizationally".

- CCP Art. 220(4)(d)(iii): This exempts "documents concerning official secrets of public officials, the submission of which is likely to harm the public interest or seriously impede the performance of public duties" (commonly referred to as "official secrets documents").

Lower Court Rulings: A Shifting Landscape

The Mito District Court (First Instance), in its decision on January 10, 2012, sided with Y, dismissing the professors' motion on the grounds that the Documents qualified as "self-use documents" exempt from production.

The professors appealed, and the Tokyo High Court, on November 16, 2012, partially altered the lower court's decision. The High Court's reasoning was more nuanced:

- Regarding "Self-Use Documents": The High Court noted that National University Corporations are subject to the Act on Access to Information Held by Incorporated Administrative Agencies, etc. (hereinafter "IAA Information Disclosure Act"), imposing disclosure obligations similar to those faced by state administrative organs under the Act on Access to Information Held by Administrative Organs. Furthermore, their officers and employees have confidentiality duties akin to national public officials, with penalties for breaches (National University Corporation Act, Arts. 18, 38 et seq.). Based on these characteristics, the High Court concluded that National University Corporations either directly fall under the definition of "the State or a local public entity" in the parenthesis of CCP Art. 220(4)(d)(ii), or that this provision should apply to them by analogy. Consequently, the Documents could not be withheld as "self-use documents" if they were used organizationally by the university's officers or staff.

- Regarding "Official Secrets Documents": The High Court then considered whether the Documents, or parts thereof, could be withheld as "official secrets documents." Assuming at least an analogous application of CCP Art. 220(4)(d)(iii) to National University Corporation employees as "public officials," the court conducted an in-camera review of the Documents (a private inspection by the judges as per CCP Art. 223(6)) and sought the opinion of the relevant supervisory government agency (as per CCP Art. 223(3)). The High Court ultimately determined that certain portions of the investigation report (specifically, the counselor's impressions) and those parts of the hearing records and meeting minutes that could identify individual speakers did qualify as "official secrets documents" and could be withheld. However, it ordered Y to produce the remaining portions of the Documents.

Dissatisfied with this partial production order, Y, the National University Corporation, filed a permitted appeal to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decision: Appeal Dismissed

On December 19, 2013, the First Petty Bench of the Supreme Court dismissed Y's appeal, upholding the High Court's approach and its partial document production order.

Key Determinations by the Supreme Court

The Supreme Court's decision rested on two crucial interpretations concerning the status of National University Corporations and their employees under the CCP's document production rules:

1. National University Corporations: Akin to State/Local Public Entities for "Self-Use Document" Exemption (CCP Art. 220(4)(d)(ii))

The Supreme Court affirmed that National University Corporations should be treated as "equivalent to the State or a local public entity" for the purposes of CCP Art. 220(4)(d)(ii). The Court highlighted several factors:

- National University Corporations are established by law for the public purpose of setting up and managing national universities (National University Corporation Act, Art. 2(1)).

- The State retains a degree of involvement in their operational management, officer appointments, and financial affairs (e.g., National University Corporation Act, Arts. 2(5), 7, 12(1), 12(8)).

- Their officers and employees are, for the application of certain penal provisions, legally deemed to be public officials (National University Corporation Act, Art. 19).

- Crucially, information held by National University Corporations is subject to the IAA Information Disclosure Act (National University Corporation Act, Art. 2(1), Appended Table 1), meaning their obligations to disclose information are "nearly the same as state administrative organs" that fall under the Act on Access to Information Held by Administrative Organs.

Given these characteristics, the Supreme Court concluded that the parenthesis in CCP Art. 220(4)(d)(ii)—which negates the "self-use document" exemption for documents possessed by the State or local public entities and used organizationally by public officials—applies by analogy (ruisui tekiyō) to documents possessed by National University Corporations and used organizationally by their officers or employees. Therefore, National University Corporations generally cannot claim the "self-use document" exemption for such organizational documents.

2. Officers and Employees of National University Corporations: Considered "Public Officials" for "Official Secrets Document" Exemption (CCP Art. 220(4)(d)(iii))

The Supreme Court also affirmed the High Court's view that officers and employees of National University Corporations should be considered "public officials" within the meaning of CCP Art. 220(4)(d)(iii), which deals with the exemption for "official secrets documents". This conclusion was based on "the provisions of the National University Corporation Act concerning the status, etc., of their officers and employees". This meant that National University Corporations could potentially withhold documents, or parts thereof, if they met the criteria for "official secrets documents" – i.e., if their disclosure would likely harm the public interest or seriously impede the performance of (what are effectively deemed) public duties by these university personnel.

Deeper Dive into the Legal Reasoning and Its Context

This Supreme Court decision is significant for its treatment of National University Corporations, which occupy a unique space in Japan's public sector.

The Evolving Status of National University Corporations:

National University Corporations were established in 2004, transforming national universities from direct state-run institutions into independent legal entities. However, as the Supreme Court noted, they retain strong ties to the state and perform public functions, particularly in education and research. Administrative law scholarship in Japan generally regards them as "administrative subjects" (gyōsei shutai) or, more specifically, "special administrative subjects" (tokubetsu gyōsei shutai) – entities established by the state or local governments to carry out specific administrative tasks. Most textbooks support the view that National University Corporations are administrative subjects, and the Supreme Court's decision aligns with this prevailing academic understanding.

The Court's reasoning acknowledges that these corporations are subject to information disclosure laws similar to government agencies. This public accountability framework was a key factor in treating them as analogous to "the State or a local public entity" regarding the limits of the "self-use document" exemption. However, the commentary also points out that National University Corporations are distinct from other incorporated administrative agencies, especially given the National University Corporation Act's (Art. 3) emphasis on academic freedom (Constitution Art. 23) and the specific nature of research, which must always be considered in the law's application.

Aligning Civil Procedure with Information Disclosure Laws:

The parenthesis in CCP Art. 220(4)(d)(ii) was introduced through a 2001 amendment to the Code of Civil Procedure. A primary purpose of this amendment was to harmonize civil litigation's document production rules with Japan's then-newly established Act on Access to Information Held by Administrative Organs, which champions the principle of open access to government documents. Similarly, the IAA Information Disclosure Act, which applies to National University Corporations, aims to ensure accountability to the public through the general principle of disclosure.

The Supreme Court's decision to apply the CCP parenthesis by analogy to National University Corporations is thus seen as consistent with the legislative intent behind the 2001 CCP reforms—promoting transparency even within the context of civil discovery. The rationale for the "self-use document" exemption is to protect the possessor's freedom of internal deliberation and activity from being chilled by unintended disclosure. It is argued that this protective interest is diminished or lost for documents that are already subject to a statutory information disclosure regime.

Balancing Transparency with the Protection of Sensitive Information:

While the ruling narrows the "self-use document" exemption for National University Corporations, it simultaneously affirms their ability to protect genuinely sensitive information by recognizing their officers and employees as "public officials" for the purpose of the "official secrets documents" exemption (CCP Art. 220(4)(d)(iii)).

This part of the decision also aligns with the spirit of the 2001 CCP amendments. These amendments introduced the "official secrets documents" category and a mechanism for courts to seek the opinion of the relevant supervisory government agency before ordering the production of potentially sensitive documents (CCP Art. 223(3)-(5)), aiming for consistency with the confidentiality obligations imposed on public officials.

Officers and employees of National University Corporations are subject to legally mandated confidentiality duties, similar in wording to those for national public servants, and these duties are backed by penal sanctions (National University Corporation Act, Arts. 18, 38). Drafters of the 2001 CCP amendment had contemplated that "deemed public officials" (minashi kōmuin)—individuals who are not formally public servants but perform highly public duties and are subject to strict, legally enforced confidentiality obligations—should fall under the scope of "public officials" in CCP Art. 220(4)(d)(iii). Examples cited included certain officials of incorporated administrative agencies and Bank of Japan employees. The Supreme Court's inclusion of National University Corporation personnel within this category is thus considered a reasonable application of the law's intent.

It is also worth noting that the term "official secrets" in the context of CCP Art. 220(4)(d)(iii) has been interpreted broadly by a previous Supreme Court decision (2005). It can include not only secrets directly belonging to the public office but also sensitive private information of individuals learned by officials during their duties, if disclosure would damage trust and impede fair public administration. This broad interpretation of "official secrets" further enables National University Corporations to protect sensitive personal data, like that often involved in harassment investigations, even while being generally subject to transparency principles.

Conclusion: Navigating Document Disclosure in University Disputes

The Supreme Court's 2013 decision provides crucial clarification on the obligations of National University Corporations regarding document production in civil lawsuits. By treating them as analogous to the State or local public entities for the "self-use document" rule, the Court reinforced the principle of transparency, reflecting their public character and obligations under information disclosure laws. Simultaneously, by recognizing their employees as "public officials" for the "official secrets document" rule, the Court acknowledged the need to protect sensitive information vital to their functions and the privacy of individuals involved.

This balanced approach has significant implications for litigation involving these important public institutions, attempting to strike a compromise between the public's right to know, the fair conduct of legal proceedings, and the protection of legitimate confidentiality interests within the academic environment. It underscores that while National University Corporations operate with a degree of autonomy, they remain firmly within the ambit of public accountability and are subject to disclosure rules designed to uphold it, tempered by safeguards for genuinely sensitive official and personal information.