Balancing Security and Privacy: Japan's Supreme Court on Workplace Belongings Inspections (August 2, 1968)

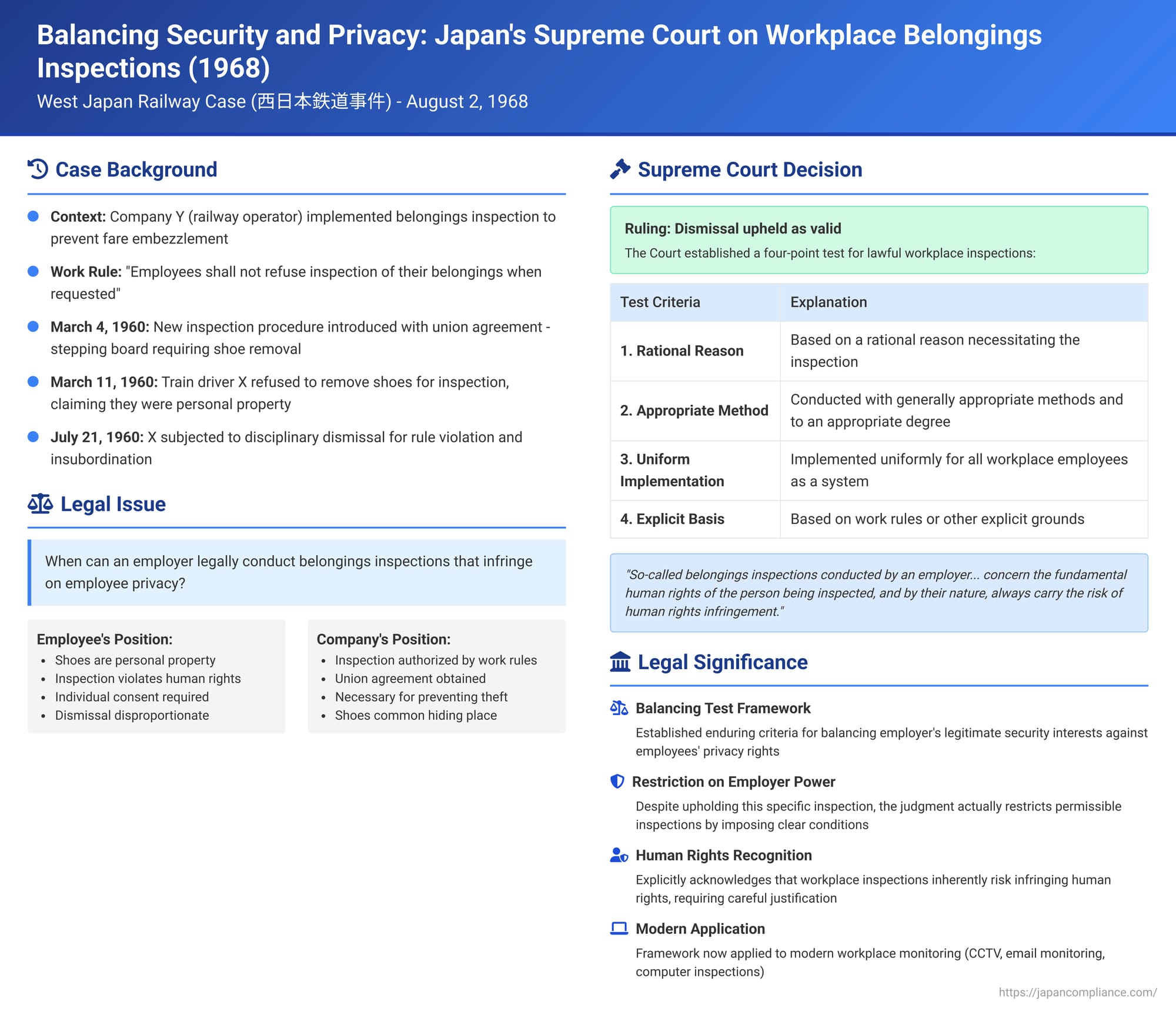

On August 2, 1968, the Second Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan delivered a landmark judgment in a case widely known as the "Nishi Nihon Tetsudo (West Japan Railway) Case" (西日本鉄道事件). This ruling established crucial legal criteria for assessing the lawfulness of employer-conducted inspections of employee belongings (所持品検査 - shojihin kensa), a practice often fraught with tension between an enterprise's need to protect its assets and maintain order, and employees' fundamental human rights, including privacy. The Court's decision, particularly its four-point test, continues to influence how such workplace measures are evaluated in Japan.

The Company's Dilemma: Fare Embezzlement and Inspection Policies

The defendant, Company Y, was a large land transportation company operating trains and buses. For some time, the company had been grappling with the issue of fare embezzlement by its crew members (drivers and conductors). To combat this, Company Y had implemented several measures, including inspections of employee belongings.

- Work Rule Provision: Article 8 of Company Y's Work Rules stated: "Employees shall not refuse inspection of their belongings when requested for the maintenance of normal operational order." The company interpreted the term "belongings" (所持品 - shojihin) broadly to encompass everything an employee might be wearing or carrying. Historically, these inspections had extended to crew members' bags, clothing, hats, and even the inside of their shoes, and according to the company, had been effective in uncovering instances of concealed fares, often found in these very items.

- Evolution of the Inspection Method and Union Involvement:

- Around August 1958, an incident involving the conduct of an inspector during a belongings check led to discussions between Company Y and the A Branch of the labor union to which the plaintiff belonged. In these meetings, it was reaffirmed that the company's policy included the removal of shoes for inspection. However, the application of this method remained somewhat inconsistent in practice.

- To address this and ensure uniformity, on March 4, 1960, Company Y proposed a change to the A Branch of the union. The proposal involved renovating the room used for inspections (a guidance room) by installing a raised wooden floor or "stepping board" (踏板 - fumita). The idea was that this setup would naturally lead employees to remove their shoes before stepping onto the board for inspection, making the process more consistent. The A Branch of theunion consented to this proposal.

- It was further agreed that there would be a brief grace period to inform all union members of the new standardized procedure, with implementation set to begin on March 7, 1960. Importantly, both parties confirmed that human rights would be respected during inspections, that company supervisors responsible for inspections would receive thorough training, and that any human rights concerns arising from the inspections would be addressed through the labor-management council. The A Branch communicated these agreements to its members, including Plaintiff X, via its official newsletter dated March 4, 1960.

The Confrontation: A Refusal to Remove Shoes

The plaintiff, X, was a train driver for Company Y. On March 11, 1960, upon completing his shift, X, along with other crew members, was directed to undergo a belongings inspection under the newly implemented procedure.

- When X's turn came, he placed his hat and the contents of his pockets onto the wooden inspection board. However, X staunchly refused to remove his shoes for inspection.

- X argued that his shoes were personal property and not "belongings" subject to the company's inspection rule. He contended that inspecting the inside of his shoes required his individual consent, which he was not giving.

- Despite instructions from the inspecting supervisor (who, it was noted, had been specifically cautioned to conduct the inspections respectfully and avoid antagonizing employees), X persisted in his refusal. No other employee refused to remove their shoes during that day's inspections.

Consequently, Company Y deemed X's refusal to remove his shoes a violation of Article 8 of the Work Rules (failure to comply with a belongings inspection request) and Article 58, Paragraph 3 (unjustly defying a work-related instruction and thereby disturbing workplace order). On July 21, 1960, Company Y subjected X to disciplinary dismissal.

X challenged this dismissal. After a complex series of provisional disposition proceedings, the main lawsuit for invalidation of the dismissal reached the lower courts. Both the Fukuoka District Court (first instance) and the Fukuoka High Court (on appeal) ultimately upheld the dismissal, finding X's refusal to be a serious breach. X then appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Four-Point Test for Lawful Inspections

The Supreme Court dismissed X's appeal, thereby affirming the validity of the disciplinary dismissal. In its judgment, the Court laid down a foundational four-point framework for determining the legality of employer-conducted belongings inspections:

The Court began by acknowledging the sensitive nature of such inspections: "So-called belongings inspections conducted by an employer on its enterprise's employees for the purpose of detecting and preventing the illicit concealment of money or goods, concern the fundamental human rights of the person being inspected, and by their nature, always carry the risk of human rights infringement."

It then stated that several factors, while relevant, do not automatically legitimize such inspections: "...even if such inspections are a necessary and effective measure for the management and maintenance of the enterprise, and are commonly practiced in other similar enterprises, and even if they are based on provisions in work rules created or amended through procedures prescribed by the Labor Standards Act, and have the consent of the employee union or a majority of the workplace employees, these facts alone do not automatically render them lawful."

The crucial determinant, according to the Court, is "the method or degree of the inspection." For a belongings inspection to be considered lawful, it must satisfy the following conditions:

- Rational Reason: It must be "based on a rational reason necessitating" the inspection.

- Appropriate Method and Degree: It must be "conducted with generally appropriate methods and to an appropriate degree."

- Uniform Implementation as a System: It must be "implemented uniformly for all workplace employees as a system."

- Explicit Basis and Employee's Duty to Comply: "When belongings inspections meeting these criteria are conducted based on work rules or other explicit grounds, then, even if there is not an absolute lack of alternative measures, employees are obligated to tolerate the inspection, unless there are special circumstances such as the method or degree being inappropriate in an individual case." The Court also added that interpreting the employee's obligation in this manner does not contravene the constitutional rights asserted by the appellant.

Application to the Shoe Inspection in X's Case

Applying this framework to the facts before it, the Supreme Court concluded:

- Interpretation of "Belongings Inspection": "Even if the inspection of the inside of shoes, involving their removal, should, as argued [by X], inherently belong to the category of a body search (身体検査 - shintai kensa), under the established facts of this case, it is not problematic to interpret that the belongings inspection stipulated in Article 8 of the work rules includes such inspection of shoes involving their removal." This was supported by the history of embezzlement where shoes were a common hiding place, and the specific agreement with the union regarding shoe removal.

- Appropriateness of the Specific Inspection: The Court found "no circumstances...to deem the method or degree of inspection inappropriate in the specific instance when X was inspected." The inspector had reportedly tried to conduct the inspection respectfully.

- Violation and Disobedience: Therefore, "X's refusal to comply cannot but be said to violate the said [work rule] provision." Furthermore, the Court found "no rational basis to specifically exclude an instruction to undergo a belongings inspection involving shoe removal" from the scope of "work-related instructions" mentioned in the disciplinary rule (Article 58, Paragraph 3).

- Justification for Dismissal: "Considering the circumstances and background leading to the disciplinary dismissal, X's refusal to remove shoes... falls under the grounds for disciplinary dismissal stipulated in Article 58, Paragraph 3 of the work rules." The dismissal was thus upheld.

Deeper Insights and Enduring Significance

This Supreme Court judgment was delivered against a societal backdrop where concerns about overly intrusive workplace inspections had been raised, including by human rights bodies, following an unrelated incident involving a bus conductor's suicide after an inspection.

- The Four Criteria as a Balancing Act: The four points articulated by the Supreme Court represent an attempt to balance the employer's legitimate interests (e.g., preventing theft, ensuring safety, protecting confidential information) with the employees' fundamental rights to privacy and dignity. These criteria have become a cornerstone for analyzing the legality of various forms of workplace inspections in subsequent Japanese case law.

- Judicial Application of the Criteria:

- Rational Reason: Courts have found rational reasons for inspections aimed at preventing theft of company products or bus fares, safeguarding confidential information, or maintaining company credit. However, inspections for overly broad purposes, such as generally "correcting private life discipline" with only a tenuous link to work improvement, have been deemed illegitimate (as seen in the Cosmo Earc Corp. Case, Osaka Dist. Ct. 2013, where compelling drivers to submit driver's licenses and mobile phones was found to be a tort).

- Appropriate Method and Degree: The method must be minimally intrusive and respectful. For example, a uniform check of bags by a guard might be acceptable, while physically patting down employees or invasively searching pockets without strong justification would likely be deemed inappropriate. The process should not be humiliating.

- Uniform Implementation: Inspections should be applied consistently as a system, not arbitrarily or in a discriminatory manner that "targets" specific individuals.

- Explicit Basis: The authority for inspections should be clearly grounded in work rules or similar explicit company policies.

- Proportionality of Discipline: The commentary highlights an important related principle: even if an inspection itself is deemed lawful and an employee's refusal constitutes a violation of work rules, any subsequent disciplinary sanction must be proportionate to the offense. A minor act of non-cooperation might not justify a severe penalty like dismissal, especially for a first offense.

- Academic Reception and Modern Relevance: While some initial criticism suggested the Supreme Court's framework might merely legitimize intrusive practices, the dominant academic view, as noted in the commentary, is that the judgment actually serves to restrict the permissibility of such inspections by setting clear conditions. These principles continue to be relevant and are now being extended by analogy to discussions around more modern forms of employee monitoring, such as the use of X-ray baggage scanners, CCTV surveillance, employer monitoring of work emails, and inspections of company-issued computers, all of which raise similar human rights and privacy considerations.

Conclusion: A Framework for Workplace Inspections

The Supreme Court's 1968 decision in the Transportation Company Y (West Japan Railway) case established a vital legal framework for workplace belongings inspections in Japan. It recognized that while employers may have legitimate reasons for conducting such inspections, these actions inherently impinge upon employees' fundamental rights and are therefore subject to strict conditions. The requirements of a rational basis, appropriate and minimally intrusive methods, uniform application, and an explicit grounding in workplace rules serve as crucial safeguards. This judgment emphasizes that any such inspection regime must be implemented with due regard for employee dignity and privacy, striking a careful balance between managerial prerogatives and individual rights.