Balancing Safety and Liberty: Japan's Supreme Court on Physical Restraints in General Hospitals

Date of Judgment: January 26, 2010, Supreme Court of Japan (Third Petty Bench)

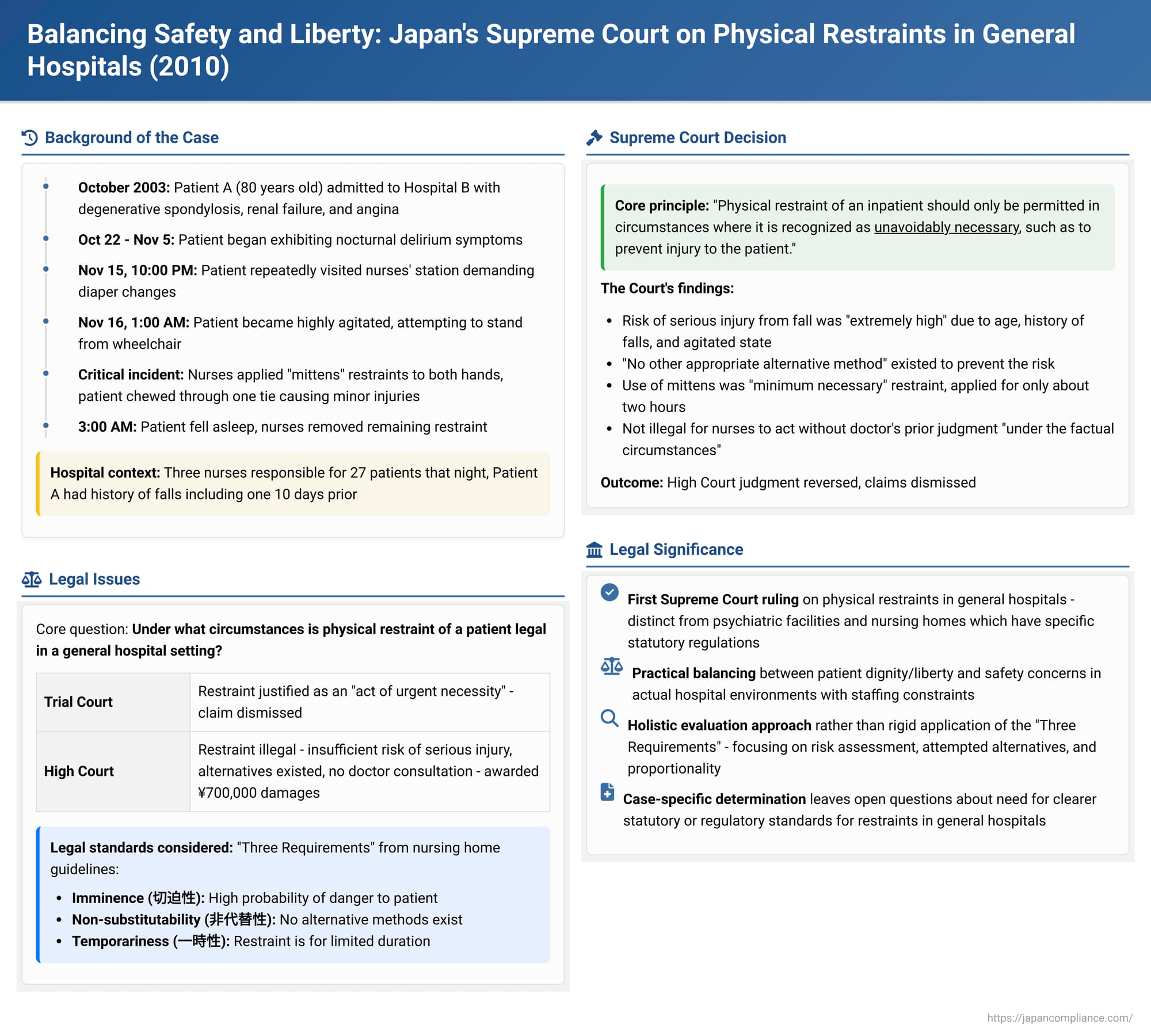

The use of physical restraints on patients in hospitals presents a profound ethical and legal dilemma, pitting the duty to ensure patient safety against the fundamental rights to liberty and dignity. This issue is particularly acute when dealing with vulnerable individuals, such as elderly patients or those experiencing delirium. A significant Japanese Supreme Court decision on January 26, 2010, addressed this sensitive matter, providing a rare top-court perspective on the legality of restraints used by nursing staff on an agitated, elderly patient in a general hospital setting.

The Case: An Elderly Patient's Nocturnal Delirium and the Nurses' Response

The case centered on Patient A, an 80-year-old man who was hospitalized on October 7, 2003, at Hospital B, operated by Defendant Y. Patient A was diagnosed with degenerative spondylosis, renal failure, and angina. While initially having difficulty walking due to lower back pain, his condition gradually improved, allowing him to move from his bed to a wheelchair to use the toilet and to stand with the aid of a handrail. His nursing care plan included wearing diapers at night.

From October 22 to November 5, Patient A began exhibiting symptoms of nocturnal delirium, characterized by confusion and agitation. On November 4, he repeatedly used the nurse call button demanding diapers and subsequently fell while attempting to return from the toilet alone in his wheelchair.

The critical events unfolded on the night of November 15-16, 2003.

- Patient A took a sleeping medication before the 9:00 PM lights-out.

- After lights-out, he frequently used the nurse call, insisting on diaper changes. Three on-duty nurses were responsible for 27 patients that night. They responded to each of Patient A's calls, often changing his diaper even if it was not soiled, in an attempt to pacify him.

- After 10:00 PM, Patient A began making repeated trips in his wheelchair to the nurses' station, loudly complaining about soiled diapers. Each time, nurses would escort him back to his room and change his diaper.

- Around 1:00 AM on November 16, during another visit to the nurses' station, Patient A became particularly agitated, loudly demanding a diaper change and attempting to stand up from his wheelchair. Concerned about the risk of a fall, the nurses moved Patient A, along with his bed, to a private room near the nurses' station.

- Despite the efforts of two nurses to calm him by talking to him and offering tea, Patient A's agitation persisted. He continued to demand diaper changes and repeatedly tried to get out of his bed.

- The Restraint: Faced with this situation, the nurses applied "mittens"—long, glove-like restraints with ties—to Patient A, securing both of his hands to the side rails of his bed.

- Patient A managed to chew through the tie of one mitten with his mouth, freeing one hand. This action resulted in a subcutaneous hemorrhage on his right wrist and an abrasion on his lower lip. Soon after, he fell asleep.

- Around 3:00 AM, observing that Patient A was asleep, the nurses removed the remaining mitten. In the early morning, he was moved back to his original hospital room.

Patient A was discharged from Hospital B on November 21, 2003, to be treated for renal failure at another facility, Hospital C. On November 1, 2004, Patient A filed a lawsuit against Defendant Y (the operator of Hospital B), seeking 6 million yen in damages. He alleged that the physical restraint and the lack of explanation to his family constituted a breach of the medical care contract and a tort. Patient A passed away on September 8, 2006, after the conclusion of the first-instance oral arguments, and his two children, Plaintiffs X, inherited the lawsuit.

The Legal Path: Conflicting Lower Court Decisions

- Trial Court: The trial court dismissed Plaintiffs X's claim. It found that the nurses' act of restraining Patient A was justified as an "act of urgent necessity" (kinkyū hinan kōi), essentially an emergency measure to prevent harm.

- High Court: The High Court reversed the trial court's decision, finding the restraint illegal. It awarded Plaintiffs X a total of 700,000 yen (500,000 yen for emotional distress and 200,000 yen for attorney fees). The High Court's reasoning included:

- There was insufficient evidence that Patient A faced an imminent risk of serious injury from a fall if not restrained.

- Patient A's delirium was likely caused by insomnia and the stress associated with using diapers. The High Court suggested that the nurses' initial "clumsy" (tsutanai) attempts to persuade Patient A that his diapers were not soiled might have exacerbated his agitation.

- Alternative measures, such as having one nurse stay with Patient A to provide comfort and wait for him to fall asleep, were not impossible. Thus, the restraint lacked "imminence" and "non-substitutability."

- The injuries Patient A sustained (wrist hemorrhage, lip abrasion) indicated that the restraint was not a "minor" intervention.

- Restraining a patient for nocturnal delirium was considered a measure requiring medical judgment, not merely "routine nursing care" (ryōyō-jō no sewa). Therefore, the nurses acting without consulting the on-call doctor was also a factor in deeming the restraint illegal.

Defendant Y (the hospital operator) appealed the High Court's decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Ruling (January 26, 2010)

The Supreme Court overturned the High Court's judgment and reinstated the trial court's decision, ultimately dismissing the plaintiffs' claims.

Core Principle: The Court began by affirming that "the physical restraint of an inpatient should only be permitted in circumstances where it is recognized as unavoidably necessary, such as to prevent injury to the patient."

Assessment of Risk to Patient A:

The Supreme Court found that the risk of Patient A suffering a serious injury from a fall was "extremely high." This conclusion was based on:

- Patient A's delirious and agitated state, including repeated attempts to get out of bed.

- His advanced age (80 years old).

- His history of falls: one four months prior at F Hospital resulting in a pelvic fracture, and another just ten days earlier at Hospital B.

Evaluation of Alternative Measures:

The Court determined that, at the time of the restraint, there was "no other appropriate alternative method" to prevent the risk of Patient A falling and injuring himself.

- Nurses had attempted to calm Patient A for approximately four hours through frequent diaper changes (even when not soiled) and by offering tea, but his agitation did not subside. The Court found it "difficult to believe that Patient A's condition would have improved if a nurse had continued to stay with him further."

- Given the staffing levels (three on-duty nurses for 27 inpatients), it was considered "difficult" for one nurse to be exclusively dedicated to Patient A for an extended period throughout the night.

- Administering stronger psychotropic medication to Patient A was deemed dangerous due to his renal failure.

Proportionality of the Restraint:

The Court considered the nature and duration of the restraint:

- Mitten restraints were used to secure both of Patient A's upper limbs to the bed.

- Patient A quickly managed to free one hand by chewing the tie.

- The nurses promptly removed the other mitten once Patient A fell asleep.

- The total effective restraint time was approximately two hours.

The Supreme Court concluded that "the said restraint, in light of Patient A's condition at the time, was the minimum necessary to prevent the risk of his falling or tumbling from bed."

Legality of the Nurses' Actions:

Based on the foregoing, the Supreme Court held that "the said restraint was an emergency unavoidable act performed by the nurses in charge of Patient A's nursing care to avoid the danger of Patient A suffering serious injury due to a fall or tumble from bed." Therefore, it did not constitute a breach of the medical care contract nor was it illegal under tort law.

The minor injuries Patient A sustained while trying to remove the mitten did not affect this judgment. Furthermore, "under the factual circumstances," the Court found no basis to deem the nurses' actions illegal merely because they did not obtain a prior judgment from the on-call doctor.

Legal and Ethical Landscape of Patient Restraint in Japan

The use of physical restraints on patients touches upon fundamental rights and is subject to legal scrutiny.

- General Principle: Restraining a person without their valid consent is generally considered illegal as it infringes upon their dignity and physical liberty.

- Specific Regulations in Certain Settings:

- Psychiatric Hospitals: The Mental Health and Welfare Act provides a legal basis for limiting a patient's actions, including physical restraint, but only to the "extent indispensable for their medical care or protection." Detailed criteria are set by Ministry notifications, permitting restraint only in specific, urgent situations (e.g., imminent suicide attempts, risk of serious self-harm, or danger to life where no alternatives exist).

- Nursing Care Facilities (under the Long-Term Care Insurance Act): Operational standards for these facilities explicitly prohibit physical restraint except "in cases where it is urgently unavoidable to protect the life or body of the user or other users." Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare guidelines further define "urgently unavoidable cases" by three cumulative requirements:

- Imminence (Kippakusei): A markedly high probability that the patient's or others' life or body will be endangered.

- Non-substitutability (Hi-daitaisei): No alternative care methods exist other than physical restraint.

- Temporariness (Ichijisei): The physical restraint is for a temporary period.

(The High Court in Patient A's case had referred to these three requirements as relevant considerations for general hospitals as well).

- General Hospitals: Unlike psychiatric hospitals or nursing care facilities, there are no specific statutes or detailed ministerial ordinances directly regulating the use of physical restraints in general hospitals in Japan. The Supreme Court's 2010 decision in Patient A's case was the first time it directly ruled on the legality of such restraints by nurses in this setting.

The Supreme Court's Nuanced Approach to "Unavoidable Necessity"

In its decision, the Supreme Court clearly stated that restraints in general hospitals are, in principle, prohibited and only permissible when "unavoidably necessary." However, the Court deliberately avoided explicitly adopting or applying the "Three Requirements" (Imminence, Non-substitutability, Temporariness) from the nursing home guidelines as a formal, general standard for all medical settings. This suggests that the Court did not intend for these criteria to become a rigid, universally applicable test for general hospitals.

Nevertheless, the Supreme Court's reasoning in Patient A's case closely mirrored the elements of these three requirements:

- It found a "extremely high" risk of serious injury (addressing imminence/severity of danger).

- It concluded there were "no other appropriate alternative methods" (addressing non-substitutability).

- It determined the restraint was the "minimum necessary" and noted its relatively short duration of about two hours (addressing proportionality and temporariness).

Thus, while not formally adopted, a similar analytical framework focusing on risk, alternatives, and proportionality guided the Court's assessment of "unavoidable necessity." The decision is largely seen as case-specific, emphasizing a holistic evaluation of all circumstances.

The Role of Medical Professionals and Consent

The Supreme Court's cautious approach to the issue of a doctor's prior involvement is noteworthy. The High Court had considered the lack of a doctor's order a factor contributing to illegality, viewing the restraint as more than simple nursing care. The Supreme Court, however, found no illegality due to the absence of a prior doctor's judgment under the specific facts of this case. This leaves open the possibility that in different circumstances, the lack of direct medical assessment or order could be a critical factor.

The principle of informed consent is central to medical ethics. For physical restraints, which are highly invasive of personal liberty, specific and individualized consent would generally be required. A blanket consent form signed upon hospital admission is unlikely to suffice. This becomes particularly complex with patients who lack decision-making capacity, such as those in a state of delirium or with advanced dementia. In such instances, as with Patient A, the justification for restraint shifts heavily towards the "unavoidable necessity" standard, as determined by the medical and nursing professionals.

Reactions and Ongoing Debate

The Supreme Court's decision in Patient A's case was met with varied reactions. Many legal commentators and healthcare professionals viewed it as a pragmatic ruling that took into account the challenging realities of nursing care, especially in environments with staffing shortages and an increasing population of elderly patients prone to confusion and falls.

However, the judgment's case-specific nature and its reluctance to set down a clear, generally applicable standard for restraints in general hospitals have also led to calls for legislative action. Critics argue that relying on case-by-case judicial determinations is insufficient and that clear statutory or regulatory guidelines are needed to provide better clarity and protection for both patients and healthcare providers in general hospital settings. The debate continues on whether existing frameworks from psychiatric or long-term care settings can or should be adapted, or if new, specific regulations are required for general hospitals.

Conclusion

The Japanese Supreme Court's 2010 decision in the case of Patient A provides an important, albeit case-specific, articulation of the legal boundaries for using physical restraints in general hospitals. It affirms that such measures, while deeply infringing on patient liberty and dignity, can be legally permissible if deemed "unavoidably necessary" to prevent a high and imminent risk of serious self-injury. This justification, however, hinges on a rigorous assessment showing that all appropriate and less restrictive alternatives have been exhausted or are unsuitable, and that the restraint employed is the minimum necessary in terms of scope and duration. The ruling underscores the immense responsibility on healthcare professionals to navigate these difficult situations with careful judgment, always prioritizing patient safety while respecting their fundamental rights. It also highlights the ongoing need for discussion and potentially clearer guidelines to govern these challenging aspects of patient care.