Japan Supreme Court 2006: National Health Insurance Premiums & Hardship Exemptions Explained

TL;DR

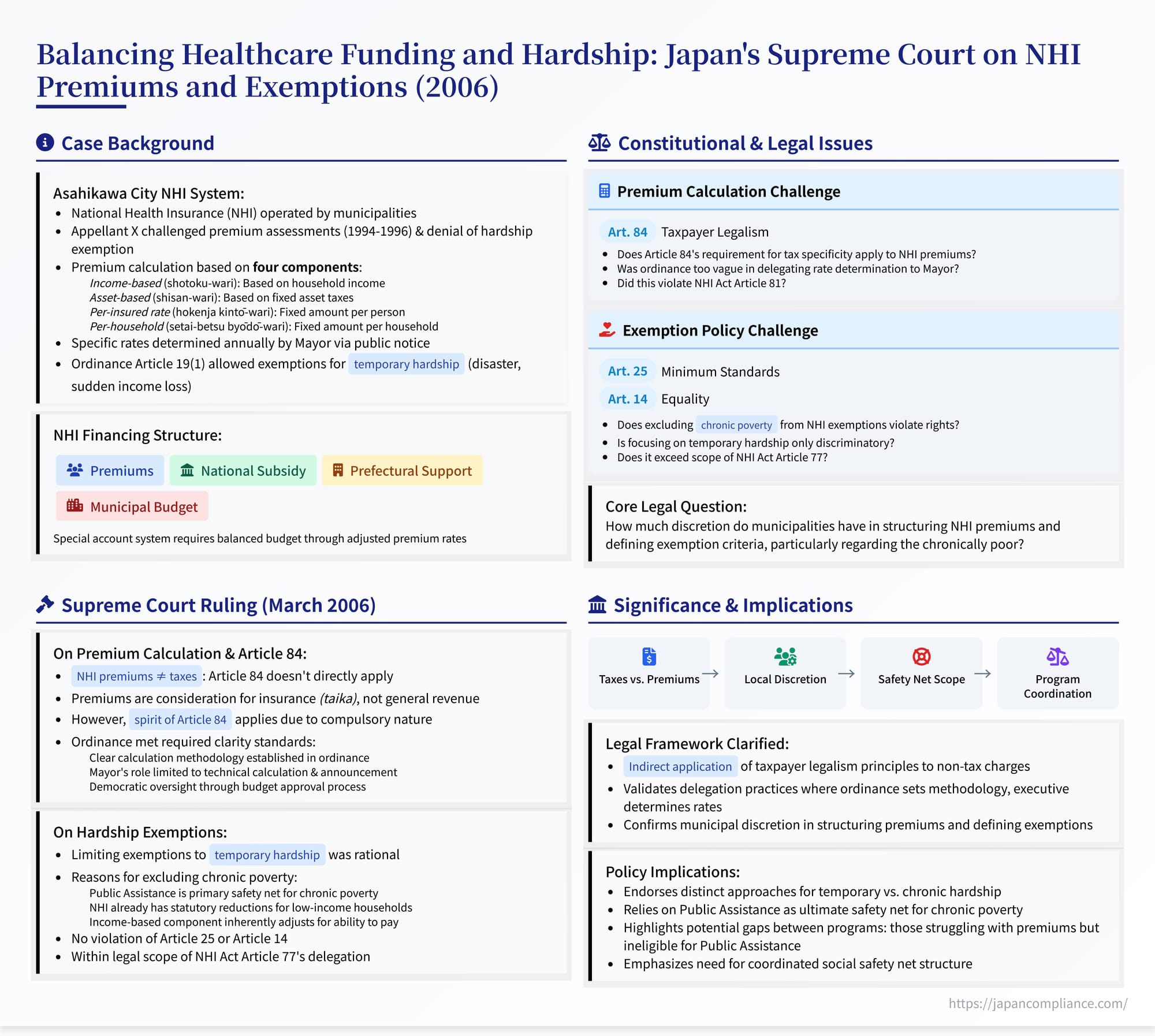

Japan’s Supreme Court Grand Bench (March 1, 2006) upheld Asahikawa City’s method of setting compulsory National Health Insurance (NHI) premiums and its narrow hardship‑exemption rule. The Court held that NHI premiums, although mandatory, are not “taxes” under Article 84 of the Constitution. Therefore, ordinances may delegate the arithmetic setting of premium rates to the mayor, provided clear calculation standards exist. Chronic poverty is expected to be dealt with through the Public Assistance Act, so limiting NHI exemptions to temporary hardship was found constitutional.

Table of Contents

- Background: NHI Premiums and Hardship in Asahikawa City

- The Constitutional and Statutory Challenges

- The Supreme Court’s Decision: Upholding the Ordinance and Assessments

- Significance and Analysis

- Conclusion

Universal healthcare systems face the ongoing challenge of balancing comprehensive coverage with sustainable funding mechanisms. A key component of this challenge involves determining how contributions (premiums or taxes) are assessed and collected, and how exceptions are made for individuals facing financial hardship. Japan's National Health Insurance (NHI) system, which primarily covers the self-employed, unemployed, and retirees not covered by employee-based insurance, relies heavily on premiums set by local municipalities. A 2006 decision by Japan's Supreme Court Grand Bench delves into the constitutional and statutory constraints on how these premiums are set and when exemptions must be granted. The case, formally the Case Concerning Request for Revocation of National Health Insurance Premium Assessment Disposition, etc. (Supreme Court, Grand Bench, Heisei 12 (Gyo-Tsu) No. 62, Heisei 12 (Gyo-Hi) No. 66, March 1, 2006), addresses fundamental questions about taxpayer legalism principles applied to insurance premiums and the scope of local government discretion in providing hardship relief.

Background: NHI Premiums and Hardship in Asahikawa City

The appellant, X, was the head of a household residing in Asahikawa City, Hokkaido. X and his wife became insured under the city's National Health Insurance (NHI) program in April 1994. NHI in Japan is operated primarily by municipalities (cities, towns, villages) acting as insurers for residents not covered by other schemes (like employees' health insurance). Funding comes from a mix of sources: premiums paid by households, national government subsidies, prefectural contributions, and transfers from the municipality's general budget. Municipalities can choose to fund their NHI programs either through premiums (hokenryō) or a designated NHI tax (kokumin kenkō hoken zei); Asahikawa City used the premium system.

For the fiscal years 1994, 1995, and 1996, Asahikawa City (referred to as Y1) issued premium assessment notices (fuka shobun) to X based on the city's NHI Ordinance (jōrei). The ordinance detailed how premiums were calculated, typically involving a combination of factors:

- Income-based portion (shotoku-wari): Based on the household's previous year's income.

- Asset-based portion (shisan-wari): Based on the household's fixed asset taxes (land and buildings).

- Per-insured flat rate (hokenja kintō-wari): A fixed amount per insured person in the household.

- Per-household flat rate (setai-betsu byōdō-wari): A fixed amount per insured household.

The specific rates applied to the income and asset portions, and the amounts for the flat-rate portions, were determined annually by the Mayor based on the estimated budget needs of the city's NHI special account (a separate account required by law for NHI finances) and then announced via public notice (kokuji). The ordinance prescribed the method for calculating the total required premium revenue (fuka sōgaku) based on projected expenditures minus projected non-premium revenues, adjusted by an expected collection rate.

X, facing financial difficulties, applied to the Mayor of Asahikawa (Y2) for a reduction or exemption (genmen) of the assessed premiums for these years. The NHI Act (Article 77) allows insurers (municipalities) to establish ordinances granting reductions or exemptions for individuals with "special reasons." The Asahikawa City Ordinance (Article 19(1)) specified grounds for such relief, including situations where individuals faced significant hardship due to disaster or a substantial decrease in income during the current year, or comparable circumstances.

The Mayor denied X's applications, issuing notices stating that X's situation did not meet the criteria specified in the ordinance's Article 19(1) (these denials are termed genmen hi-gaitō shobun). X's administrative appeal to the prefectural NHI review board was also unsuccessful.

The Constitutional and Statutory Challenges

X brought the case to court, challenging both the premium assessments themselves and the denial of the hardship exemption. The core arguments relevant to the Supreme Court appeal were:

- Violation of Taxpayer Legalism (Constitution Art. 84) and NHI Act Art. 81: X argued that the way Asahikawa calculated and set NHI premiums was unlawful and unconstitutional.

- The ordinance's method for determining the total required premium revenue (the fuka sōgaku) was claimed to be vague and indeterminate.

- Crucially, the ordinance did not specify the actual premium rates but delegated their determination to the Mayor, to be announced later by public notice. X argued this violated the principle of taxpayer legalism enshrined in Constitution Article 84 ("No new taxes shall be imposed or existing ones modified except by law or under such conditions as law may prescribe"), or at least the principles underlying it, as applied to compulsory public charges like NHI premiums.

- This delegation and lack of specificity in the ordinance itself was also argued to violate NHI Act Article 81, which requires premium details (assessment amount, rates, deadlines, etc.) to be stipulated by ordinance in accordance with standards set by cabinet order.

- Violation Regarding Hardship Exemptions (NHI Act Art. 77, Const. Arts. 25 & 14): X argued that the ordinance's hardship exemption provision (Article 19(1)) was itself illegal and unconstitutional because it failed to provide relief for individuals experiencing chronic poverty (kōjō-teki ni seikatsu ga konkyū shiteiru jōtai ni aru mono). By limiting exemptions primarily to temporary hardship (disaster, sudden income loss in the current year), the ordinance allegedly:

- Exceeded the scope of delegation allowed by NHI Act Article 77 (which permits exemptions for "special reasons," argued to potentially include chronic poverty).

- Violated Constitution Article 25 (right to minimum standards) by imposing unaffordable premium burdens on the chronically poor without adequate relief mechanisms within the NHI system itself.

- Violated Constitution Article 14 (equality) by unreasonably discriminating against the chronically poor compared to those experiencing temporary hardship, or compared to higher-income individuals who could afford the premiums.

The District Court initially ruled in X's favor, finding the premium assessment method flawed. However, the Sapporo High Court reversed this decision, upholding both the premium assessments and the denial of exemptions. X then appealed to the Supreme Court, which decided the case sitting as the Grand Bench due to the constitutional questions involved.

The Supreme Court's Decision: Upholding the Ordinance and Assessments

The Supreme Court Grand Bench unanimously dismissed X's appeal, finding Asahikawa City's NHI ordinance and the resulting actions constitutional and lawful.

1. Reasoning on Constitution Article 84 (Taxpayer Legalism) and NHI Act Article 81:

The Court undertook a detailed analysis of whether taxpayer legalism principles apply to NHI premiums and, if so, whether the Asahikawa ordinance met the required standards.

- NHI Premiums Are Not "Taxes" under Article 84: The Court first drew a clear distinction. Taxes, under Article 84, are compulsory levies imposed by the state or local governments under their sovereign taxing power to fund general expenditures, without a direct quid pro quo for the taxpayer. NHI premiums, in contrast, are collected as consideration (taika) for the specific benefit of being covered by NHI and being eligible to receive healthcare benefits. While NHI enrollment and premium payment are compulsory, and the system relies heavily on public subsidies, the Court held this doesn't sever the link between the premium and the insurance benefit eligibility. The compulsory nature stems from the social insurance goal of risk-pooling across the entire eligible population. Therefore, Constitution Article 84 does not directly apply to NHI premiums collected under the NHI Act. (The Court noted, however, that if a municipality chooses the NHI Tax option under the Local Tax Act, Article 84 would apply because the levy takes the form of a tax).

- Indirect Application of Article 84's Principles: Despite finding Article 84 not directly applicable, the Court stated that the article embodies a broader constitutional principle rooted in the rule of law: imposing obligations or limiting rights requires a clear legal basis. Therefore, non-tax public charges (kōka) are not entirely outside this principle's scope simply because they aren't taxes. Public charges that resemble taxes in their degree of compulsion, such as compulsory NHI premiums, are subject to the spirit or purport (趣旨, shushi) of Article 84.

- Required Level of Clarity for Premiums: However, the degree of clarity required in the law or ordinance setting the assessment criteria for such non-tax charges depends on the specific nature, purpose, and coerciveness of the charge. Because NHI premiums have the specific purpose of funding the NHI program based on social insurance principles (mutual aid), the required level of clarity in the ordinance must be judged considering these characteristics, alongside the compulsory nature.

- Assessment of Asahikawa's Ordinance: The Court then examined the ordinance's premium-setting mechanism:

- Calculation Standard: The method of calculating the total premium revenue needed (fuka sōgaku)—based on estimated expenditures minus estimated non-premium revenues—was deemed rational and consistent with the purpose of NHI premiums (funding the program's costs). The ordinance clearly specified the categories of expenditures and revenues to be included in these estimates.

- "Based On" Clause and Collection Rate: The phrase allowing the total assessment amount to be calculated "based on" the projected budget deficit was interpreted reasonably as permitting an adjustment for expected uncollectible premiums (using a projected collection rate, yotei shūnō-ritsu) to ensure sufficient actual revenue. This adjustment was not considered impermissibly vague.

- Rate Calculation: The ordinance clearly defined how the total assessment amount was allocated among the four premium components (income, asset, per-person, per-household) using set ratios, and how the rate for each component was mathematically derived from the allocated amount and the relevant base (total income, total assets, number of insured, number of households).

- Delegation to Mayor for Calculation and Notice: The Court concluded that the ordinance itself set clear calculation standards. The delegation to the Mayor (Article 12(3)) was limited to the technical and specialized task of making the necessary estimates (of expenditures, revenues, collection rates) within reasonable bounds, performing the calculations according to the ordained formula, and formally determining and publishing the resulting rates via public notice. The Court noted that no arbitrary judgment could enter into the rate calculation once the total assessment amount was estimated based on the clear criteria. Furthermore, this process was subject to democratic control through the city council's deliberation and approval of the NHI special account budget (containing the estimates) and settlement reports.

- Timing of Rate Announcement: The fact that the final rates were announced after the start of the fiscal year (April 1st) was also found acceptable. Since the calculation method was fixed by the ordinance beforehand, announcing the specific rates later based on updated estimates did not violate legal stability.

- Conclusion on Legality/Constitutionality: Therefore, the Asahikawa ordinance provided sufficiently clear standards, the delegation to the Mayor was permissible, and the process did not violate NHI Act Article 81 or the principles underlying Constitution Article 84.

2. Reasoning on Reduction/Exemption Provisions (NHI Act Art. 77, Const. Arts. 25 & 14):

The Court then turned to the challenge against the ordinance's hardship exemption provision (Article 19(1)) for excluding chronically poor individuals.

- Scope of Delegation (Art. 77): NHI Act Article 77 grants municipalities the discretion ("may... reduce or exempt") via ordinance to provide relief for those with "special reasons." The Court interpreted this as permissive, not mandatory, delegation.

- Rationale for Excluding Chronic Poverty from Exemptions: The Court found Asahikawa's choice to limit exemptions under this provision to cases of temporary hardship (disaster, sudden income loss) reasonable and within the scope of delegation. Its reasoning integrated several points:

- Public Assistance as Primary Safety Net: The NHI Act itself anticipates that individuals in chronic poverty may be eligible for comprehensive support, including medical aid, under the Public Assistance Act, and generally excludes them from NHI eligibility if they receive such assistance (NHI Act Art. 6(vi)). This implies the legislature views Public Assistance as the primary mechanism for addressing chronic poverty.

- Existing NHI Mechanisms for Low Income: The NHI system already contains mechanisms specifically designed to mitigate the burden on low-income households before the exemption stage: (a) the flat-rate premium components (per-person and per-household) are subject to statutory reductions (gengaku) for households below certain income thresholds (implemented via Ordinance Art. 17 based on NHI Act Art. 81 and related cabinet orders), addressing the regressive nature of flat-rate levies; and (b) the income-based premium component (shotoku-wari) is inherently linked to ability to pay, being calculated based on the previous year's income.

- Purpose of Article 77 Exemptions: Given these other provisions, limiting the additional discretionary exemptions under Article 77/Ordinance Article 19(1) to addressing temporary inability to pay due to unforeseen changes within the current assessment year (when the income-based component reflects the previous year's income) was deemed a rational policy choice consistent with the overall statutory scheme.

- Conclusion on Constitutionality (Arts. 25 & 14): Based on this analysis, the Court concluded:

- The ordinance provision (Article 19(1)), by focusing exemptions on temporary hardship, was not markedly lacking in rationality.

- It did not constitute unreasonable discrimination against the economically weak (chronically poor), given the overall structure of NHI and the existence of Public Assistance.

- Therefore, the ordinance provision itself did not violate Constitution Article 25 or Article 14.

- Consequently, denying X (whose hardship appeared chronic rather than temporary under the ordinance's definition) an exemption based on this valid provision also did not violate Article 25.

The Court affirmed the High Court's judgment upholding the denial of exemptions.

Significance and Analysis

The 2006 Grand Bench decision in the Asahikawa NHI premium case offers important clarifications on the legal framework governing compulsory social insurance contributions in Japan.

- Constitutional Scrutiny of Premiums vs. Taxes: The ruling definitively established that while Constitution Article 84's strict taxpayer legalism requirements do not directly apply to NHI premiums (unlike NHI taxes), the underlying constitutional principle demanding a clear legal basis for compulsory financial levies does apply. This requires ordinances setting premiums to have sufficiently clear standards, though the Court allows for flexibility given the specific nature of social insurance financing, which must respond to variable costs like healthcare expenditures.

- Permissible Delegation: The decision validates a common practice in Japanese local governance where ordinances set the framework and calculation methodology, while delegating the final determination of rates or specific amounts (based on variable factors like budget estimates) to the executive branch (Mayor), often implemented through public notices. The Court found this permissible provided the ordinance sets clear standards, the delegated task is largely technical or involves bounded discretion, and mechanisms for democratic oversight (like budget review) exist.

- Scope of Hardship Exemptions: Perhaps most significantly for social policy, the judgment strongly endorsed the distinction between temporary hardship and chronic poverty in the context of NHI premium relief. It confirmed the view that the NHI system's internal hardship mechanisms (like Article 77 exemptions) are primarily intended for temporary situations, while chronic poverty is expected to be addressed mainly by the separate Public Assistance system.

- Reliance on Public Assistance: This reliance on Public Assistance as the ultimate safety net for those unable to afford NHI premiums, even if chronically poor but potentially above the strict Public Assistance eligibility threshold, remains a point of ongoing debate. Critics argue this can leave a gap for low-income individuals and families who struggle with NHI premiums but do not qualify for, or face barriers to accessing, Public Assistance. The ruling highlights the segmentation of Japan's social safety net and the crucial role of coordination (or lack thereof) between different programs.

- Local Government Discretion: The decision affirms the significant discretion granted to municipalities (as NHI insurers) in designing the specifics of their premium structures and exemption policies, as long as they operate within the framework established by national law (NHI Act and related orders) and constitutional principles.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 2006 decision upheld the Asahikawa City NHI ordinance, finding its method for setting premiums sufficiently clear and the delegation to the Mayor permissible under the principles underlying Constitution Article 84. It also ruled that limiting hardship exemptions primarily to cases of temporary income loss or disaster, thereby excluding those in chronic poverty from this specific relief mechanism within the NHI system, did not violate the NHI Act's delegation provision or constitutional guarantees under Articles 25 and 14. The judgment underscores the distinction between social insurance premiums and taxes, confirms the broad discretion of local governments in implementing NHI, and reinforces the legal framework that directs individuals facing chronic poverty primarily towards the Public Assistance system rather than relying solely on hardship exemptions within the NHI scheme itself.