Balancing Harms: Japanese Supreme Court on 'Necessity' for Provisional Injunctions in M&A Exclusivity Disputes

Date of Supreme Court Decision: August 30, 2004

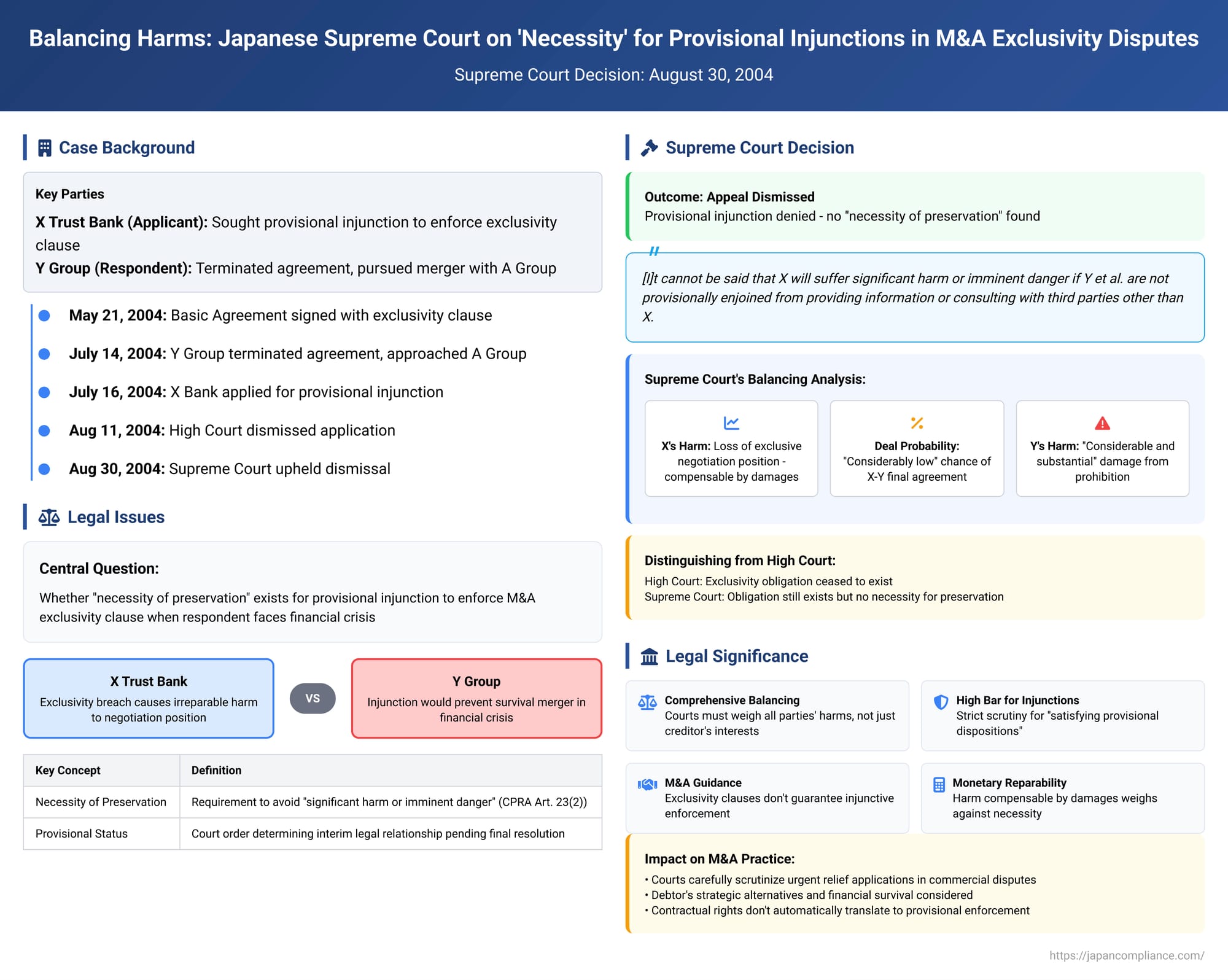

In the high-stakes world of corporate mergers and acquisitions (M&A), preliminary agreements often include exclusivity clauses designed to prevent one party from negotiating with others for a certain period. When such an agreement breaks down and one party seeks to enforce this exclusivity through urgent court intervention, Japanese courts are tasked with a delicate balancing act. A pivotal decision by the Third Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan on August 30, 2004 (Heisei 16 (Kyo) No. 19), provides crucial insights into how the "necessity of preservation" (保全の必要性 - hozen no hitsuyōsei) is assessed for a "provisional disposition to determine a provisional status" (仮の地位を定める仮処分 - kari no chii o sadameru karishobun), particularly when granting such an injunction could have severe consequences for the respondent.

The Factual Setting: A Major Banking Alliance Unravels

The dispute arose from a proposed major business reorganization and alliance between two prominent financial groups in Japan: X Group, represented by X Trust Bank (the creditor/applicant for the provisional disposition), and Y Group, which included Y Trust Bank and other entities (Y et al., the debtors/respondents).

- The Basic Agreement and Exclusivity Clause: On May 21, 2004, X Group and Y Group entered into a "Basic Agreement" (kihon gōi) outlining their intent to pursue this "Collaborative Business Development." This agreement included a critical exclusivity clause (the "Honken Jōkō"), which stipulated that "Each party shall not, directly or indirectly, provide information to or consult with any third party regarding transactions, etc., that may conflict with the purpose of this Basic Agreement." The parties then began negotiating the detailed terms of a definitive final agreement.

- Y Group's Change of Course: However, by July 2004, Y Group faced severe financial difficulties. Its management concluded that the only way to navigate this crisis was to abandon the Basic Agreement with X Group and instead pursue a comprehensive merger with a different entity, A Group, which would also involve Y Trust Bank. Consequently, on July 14, 2004, Y et al. formally notified X Trust Bank of their termination of the Basic Agreement and simultaneously announced their approach to A Group for a merger.

- X Bank's Application for Provisional Disposition: Two days later, on July 16, 2004, X Trust Bank applied to the Tokyo District Court for a provisional disposition. X Bank argued that Y Group's commencement of merger talks with A Group constituted a breach of the exclusivity clause, infringing upon X Bank's exclusive negotiation rights. X Bank sought an order prohibiting Y et al. from providing information to, or consulting with, any third party (including A Group) concerning the transfer or succession of Y Trust Bank's relevant businesses, or any related mergers, company splits, or business tie-ups, until March 31, 2006.

The Lower Courts' Decisions: A Focus on the Underlying Right

The lower courts offered contrasting views:

- Tokyo District Court: Initially, on July 27, 2004, the District Court granted X Bank's application, finding it evident that X Bank would suffer significant harm or was in imminent danger if Y Group's actions were not restrained. After Y et al. filed an objection, the District Court, on August 4, 2004, affirmed its earlier decision to grant the provisional disposition.

- Tokyo High Court: Y et al. appealed this decision. On August 11, 2004, the Tokyo High Court reversed the District Court's rulings and dismissed X Bank's application. The High Court's primary reasoning was that the trust relationship between X Group and Y Group had fundamentally broken down, making it impossible to expect any further good-faith negotiations towards finalizing their originally envisioned collaboration. Consequently, the High Court concluded that the exclusivity clause, by its very nature, had lost its future effect, leaving no existing right for X Bank to enforce via an injunction.

X Trust Bank then obtained permission to appeal the High Court's decision to the Supreme Court. (Meanwhile, on August 12, 2004, Y Group and A Group had already signed their own basic agreement for a merger.)

The Supreme Court's Shift in Focus: "Necessity of Preservation" Takes Center Stage

The Supreme Court, in its decision of August 30, 2004, dismissed X Trust Bank's appeal, thereby upholding the High Court's outcome (the dismissal of the provisional disposition application) but on significantly different legal grounds.

- Existence of the Claimed Right (Exclusivity Obligation):

The Supreme Court first addressed the High Court's finding that Y et al.'s obligations under the exclusivity clause had ceased to exist. The Supreme Court disagreed with this part of the High Court's reasoning. It stated that, based on the facts, the exclusivity clause was intended to facilitate smooth and efficient negotiations towards a final agreement by preventing third-party interference. While acknowledging that if the possibility of reaching such a final agreement between X and Y et al. became, from a common-sense societal perspective, non-existent, then the exclusivity obligation would also cease. However, the Court found that although the likelihood of an X-Y final deal was now "considerably low" given Y's termination notice and active pursuit of the A Group merger, it could not yet be said that such a possibility was entirely non-existent. Therefore, the Supreme Court concluded that Y et al.'s obligations under the exclusivity clause had not yet technically ceased to exist. - The Crucial Test: "Necessity of Preservation" (Civil Provisional Remedies Act Art. 23(2)):

Having found that X Bank still, at least formally, had a right to enforce, the Supreme Court then turned to what it considered the decisive issue: whether the requirements for granting a provisional disposition to determine a provisional status were met. Specifically, it focused on the "necessity of preservation" criterion outlined in Article 23, Paragraph 2 of the Civil Provisional Remedies Act. This provision requires that such a provisional disposition is granted only "when it is necessary to avoid significant harm or imminent danger to the creditor regarding the disputed legal relationship."The Supreme Court undertook a comprehensive balancing of several factors:- Nature of Harm to X Trust Bank (the Creditor):

The Court carefully defined the nature of the harm X Bank would suffer if Y et al. were allowed to negotiate with A Group in breach of the exclusivity clause. It reasoned that since the Basic Agreement did not guarantee the conclusion of a final deal, X Bank's harm was not the loss of the profits it might have gained from the completed Collaborative Business Development. Instead, the harm was the infringement of X Bank's expectation to negotiate with Y et al. from an advantageous, exclusive position, free from third-party interference.

The Court then assessed this type of harm (loss of an advantageous negotiating position) as not necessarily being so severe that it could not be adequately compensated by monetary damages in a subsequent lawsuit. - Probability of the Underlying Right's Fruition (i.e., the X-Y Deal):

The Court re-emphasized its earlier finding that the likelihood of X Group and Y Group actually concluding their originally planned Collaborative Business Development was now "considerably low." This low probability diminished the weight of the harm X Bank would suffer from losing its exclusive negotiation window. - Harm to Y et al. (the Debtors) if the Injunction Were Granted:

The provisional injunction sought by X Bank was extensive. It aimed to prohibit Y et al. from providing information to, or consulting with, any third party regarding the transfer of Y Trust Bank's businesses for a long period (until March 31, 2006, nearly two years).

The Supreme Court noted Y Group's precarious financial situation, which had driven their decision to seek a merger with A Group as a means of survival. Under these circumstances, imposing such a broad and lengthy prohibition on Y et al. from seeking alternative strategic options would inflict "considerable and substantial" damage upon them. - The Balancing Act – Conclusion on "Necessity":

After "comprehensively considering" all these elements—the nature of X Bank's potential loss and its potential for monetary compensation, the very low likelihood of the original X-Y deal succeeding, and the severe prejudice that Y et al. would suffer if the injunction were granted—the Supreme Court concluded: "[I]t cannot be said that X will suffer significant harm or imminent danger if Y et al. are not provisionally enjoined from providing information or consulting with third parties other than X."

Therefore, the application for the provisional disposition was found to lack the requisite "necessity of preservation" under Article 23, Paragraph 2 of the Civil Provisional Remedies Act.

- Nature of Harm to X Trust Bank (the Creditor):

Key Takeaways and Implications

This Supreme Court decision, arising from a highly publicized M&A battle, offers several important insights into the application of Japanese provisional remedy law:

- High Bar for "Satisfying" Provisional Dispositions: Provisional dispositions that effectively grant the applicant a significant part of the relief they would obtain from a final judgment (often termed "satisfying provisional dispositions" or 満足的仮処分 - manzoku-teki karishobun) are subject to strict scrutiny. The "necessity of preservation" threshold is notably high.

- Comprehensive Balancing of Factors for "Necessity": The Supreme Court explicitly engaged in a detailed balancing of harms and probabilities. This demonstrates that the assessment of "significant harm or imminent danger" is not a one-sided inquiry focused solely on the creditor's perspective. It involves a holistic evaluation of:

- The nature of the creditor's alleged harm and its reparability through subsequent monetary damages.

- The strength or likelihood of the creditor's underlying claim ultimately succeeding (the "preserved right"). The less likely the final deal, the less "significant" the harm from losing exclusivity.

- The extent and nature of the harm or prejudice that the debtor would suffer if the provisional measure were granted.

- Significance of Debtor Hardship in the "Necessity" Analysis: This decision prominently features the potential harm to the debtor (Y et al.) as a key factor in denying the injunction. While some older legal theories debated whether debtor hardship should be considered under the "necessity" rubric (arguing it's addressed by the security deposit required from the creditor, or in subsequent objection proceedings), this Supreme Court ruling firmly integrates it into the overall assessment of whether granting the provisional remedy is truly "necessary" to avoid significant harm to the creditor. This aligns with modern civil procedure trends that emphasize balancing the interests of all parties, even at the provisional stage, and with the procedural guarantee of (usually) hearing the debtor before issuing such a disposition (CPRA Art. 23(4)).

- Guidance for M&A and Commercial Disputes: As a high-profile case involving an exclusivity clause in an M&A context, this decision provides critical guidance for similar commercial disputes. It signals that Japanese courts will carefully scrutinize applications for urgent injunctive relief, particularly when such relief could derail a party's crucial strategic alternatives, and will weigh the real-world impact on all parties involved. The mere existence of a contractual right (like an exclusivity clause) does not automatically translate into an entitlement to injunctive enforcement at the provisional stage if the broader "necessity" criteria, including the balance of hardships, are not met.

- Focus on Necessity Can Sidestep Full Merits Adjudication at Provisional Stage: It's noteworthy that the Supreme Court, while finding that the exclusivity obligation technically still existed, ultimately decided the case based on the lack of "necessity of preservation." This approach—resolving an application for a provisional remedy by focusing on the necessity requirement if it provides a clearer path than a deep dive into the ultimate merits of the underlying claim—is a common judicial strategy in urgent proceedings.

Concluding Thoughts

The Supreme Court's August 30, 2004, decision in the X Trust Bank v. Y Group case is a landmark in understanding the "necessity of preservation" requirement for provisional dispositions in Japan, especially those determining a provisional status. While not invalidating the exclusivity clause itself under the specific circumstances, the Court denied injunctive relief by meticulously weighing the nature of the applicant's harm, the low probability of their original deal succeeding, and, crucially, the substantial damage an injunction would inflict on the respondents who were pursuing an alternative merger for their financial survival. This judgment underscores a comprehensive, balancing-of-interests approach, ensuring that powerful provisional remedies are reserved for situations where truly significant and irreparable harm to the applicant is imminent and where the impact on the respondent is also carefully considered. It remains a key reference for parties involved in complex commercial negotiations and potential M&A disputes in Japan.