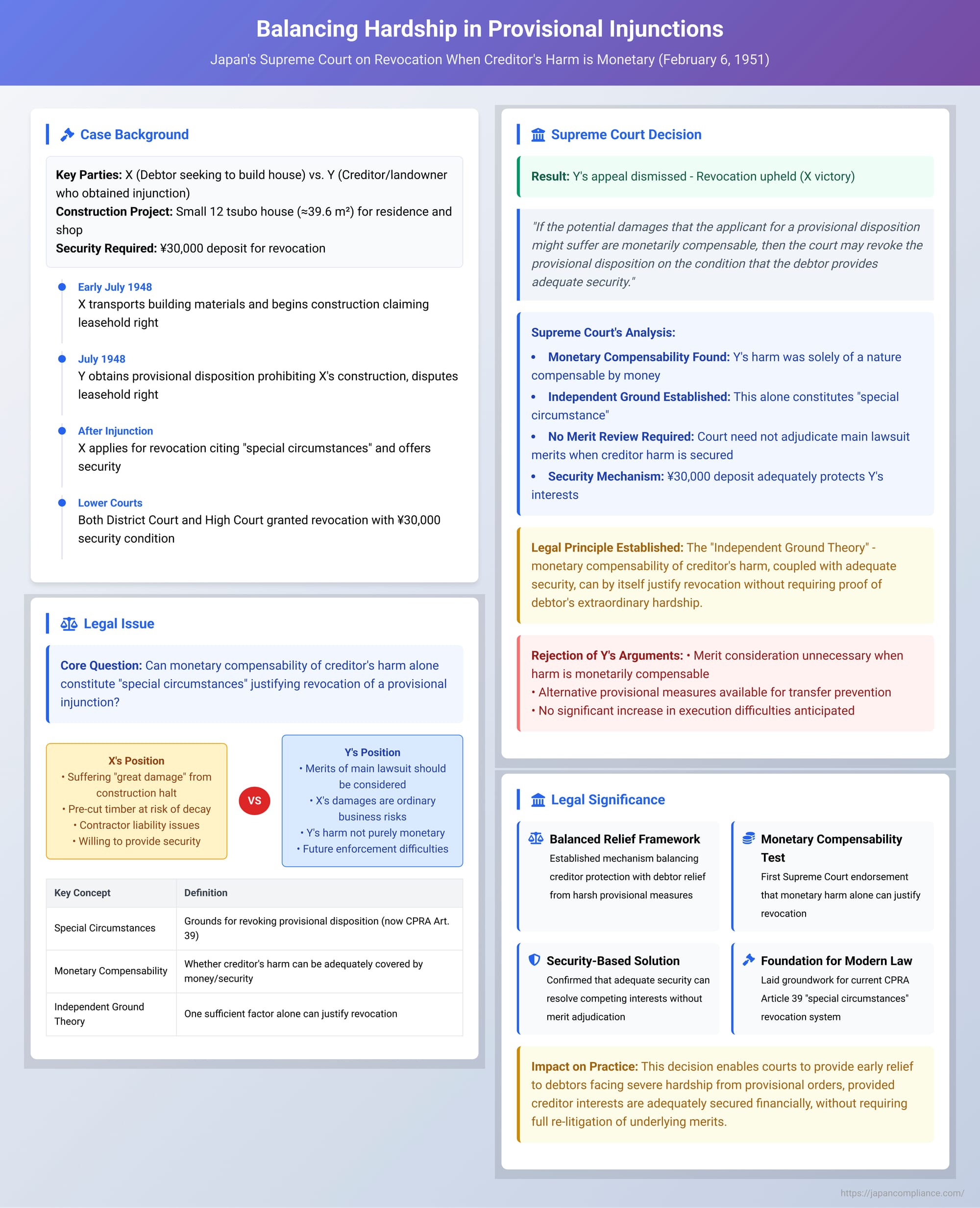

Balancing Hardship in Provisional Injunctions: Japan's Supreme Court on Revocation When Creditor's Harm is Monetary

Date of Supreme Court Decision: February 6, 1951

Provisional dispositions (仮処分 - karishobun) in Japanese law, such as an injunction prohibiting a certain activity like construction, are powerful interim measures designed to protect a claimant's rights pending a final resolution of a dispute. However, because these orders can be issued swiftly and may impose significant burdens on the party restrained (the debtor), the law provides mechanisms for their revocation. One such mechanism is the "revocation of a provisional disposition due to special circumstances" (特別の事情による保全取消し - tokubetsu no jijō ni yoru hozen torikeshi), now codified in Article 39 of the Civil Provisional Remedies Act (CPRA), and formerly under Article 759 of the old Code of Civil Procedure. A pivotal 1951 Supreme Court of Japan decision (Showa 24 (O) No. 230) shed light on what constitutes such "special circumstances," particularly focusing on situations where the harm the original applicant (the creditor) might suffer due to the debtor's actions can be adequately compensated by money.

The Factual Backdrop: A Construction Halt and Competing Hardships

The case involved X (the debtor in the provisional disposition and applicant for its revocation) and Y (the creditor who obtained the initial provisional disposition).

- The Dispute and Construction: X claimed to possess a leasehold right on land owned by Y. Intending to build a small house of approximately 12 tsubo (around 39.6 square meters) for personal residence and a small shop, X transported building materials to the site and commenced construction work in early July 1948.

- The Provisional Disposition: Y contested X's claim, asserting that any leasehold right X might have had had already extinguished. Y successfully applied to the court and obtained a provisional disposition order prohibiting X from continuing with the new construction. Following this, Y initiated a main lawsuit against X seeking the removal of any existing structures and the eviction of X from the land.

- X's Application for Revocation: Faced with the construction halt, X applied to the court for the revocation of the provisional disposition, citing "special circumstances" and offering to provide security.

- Lower Court Rulings on Revocation: Both the Oita District Court (first instance) and the Fukuoka High Court (on appeal) granted X's application. They ordered the revocation of the construction prohibition provisional disposition on the condition that X deposit ¥30,000 as security.

The Fukuoka High Court reasoned that:- Harm to X (Debtor): If the provisional disposition were to remain in effect, X would suffer "great damage." The pre-cut timber and other building materials already on site were at risk of decay, and X faced potential liability for damages to the building contractor X had engaged.

- Harm to Y (Creditor): On the other hand, the damage Y might suffer if the provisional disposition were revoked (allowing X to complete the building) would primarily be the loss of use and profit from the land for the period it would take Y to obtain a final judgment in the main lawsuit (if Y were to win) and then enforce the complete eviction of X and removal of the structure. The High Court deemed this type of harm to be "fully compensable by monetary payment" through the security X would provide.

- The High Court concluded that this balance of circumstances—significant, potentially irreparable harm to X if the injunction continued, versus monetarily compensable harm to Y if it was lifted with security—constituted "special circumstances" warranting revocation.

Y, dissatisfied with the revocation, appealed to the Supreme Court. Y argued, among other things, that the merits of the underlying main lawsuit (regarding the leasehold right) should be considered; that X's alleged damages were merely ordinary business risks; and that Y's own damages were not purely monetary and that revoking the injunction would make future enforcement of a favorable judgment difficult or impossible.

The Supreme Court's Decision: Monetary Compensability of Creditor's Harm as a Key Factor

The Supreme Court, in its decision of February 6, 1951, dismissed Y's appeal and upheld the revocation of the provisional disposition. The Court's reasoning centered heavily on the nature of the potential harm to Y, the original applicant for the injunction:

- Core Holding: The Supreme Court found the High Court's assessment—that Y's (the creditor's) potential damages were solely of a nature that could be compensated by money—to be appropriate and ultimately correct.

- The "Independent Ground" Principle: The Court articulated a crucial principle: If the potential damages that the applicant for a provisional disposition (the creditor) might suffer (should the debtor be allowed to proceed with the enjoined act) are monetarily compensable, then the court may revoke the provisional disposition on the condition that the debtor provides adequate security to cover such potential damages. This monetary compensability, coupled with security, can, by itself, constitute a "special circumstance" justifying revocation.

- No Necessity to Adjudicate Other Disputed Issues: In such cases, where the creditor's harm is deemed monetarily compensable and is secured, the court is not required to delve into other contested issues, such as the underlying merits of the main lawsuit, before deciding to revoke the provisional disposition. The ability to secure the creditor against monetary loss becomes a dominant factor.

- Application to Y's Arguments:

- Regarding Y's arguments that the merits of the main case should have been considered by the High Court (Y's points 1-3), the Supreme Court stated that since the High Court had determined Y's potential harm was monetarily compensable, its decision to revoke the provisional order without ruling on these other matters was not illegal.

- Even if the High Court might have erred in its assessment of the specifics of X's (the debtor's) harm (Y's point 4), as long as the finding that Y's (the creditor's) harm was monetarily compensable stood, that alone could qualify as a "special circumstance." Thus, the High Court's ultimate conclusion to revoke was deemed correct.

- Concerning Y's argument about non-monetary harm and future execution difficulties (Y's point 5), the Supreme Court was unpersuaded. It noted that if X were to complete the house and then attempt to transfer it to a third party, Y could seek a different type of provisional disposition (e.g., an injunction against transfer) to protect their interests. The Court did not foresee a significant increase in execution difficulties for Y merely because the initial construction prohibition was lifted.

Understanding "Revocation due to Special Circumstances" (CPRA Art. 39)

This 1951 Supreme Court decision, though rendered under the old Code of Civil Procedure (Article 759), laid foundational principles for the current system of "revocation due to special circumstances" found in Article 39 of the Civil Provisional Remedies Act (CPRA) of 1989.

- Purpose of the System: Provisional dispositions, unlike provisional attachments for monetary claims (which can often be lifted if the debtor deposits security equivalent to the claim), are typically aimed at preserving a specific state of affairs or a particular asset. This is often because the underlying right cannot be adequately satisfied by monetary compensation. Therefore, such dispositions generally cannot be revoked merely by the debtor offering security.

- However, provisional dispositions can be issued rapidly, sometimes without a full initial hearing for the debtor. This can lead to situations where the debtor experiences severe and unanticipated hardship. The "special circumstances" revocation mechanism (now CPRA Art. 39) addresses this by allowing a court to revoke a provisional disposition if specific conditions are met, usually requiring the debtor to provide security. This aims to balance the interests of the creditor (who needs protection) and the debtor (who may be unduly burdened by the provisional order).

- What Constitute "Special Circumstances"?

- Traditionally, two main prongs were considered:

- The debtor would suffer "extraordinary damage" (償うことができない損害 - tsugunau koto ga dekinai songai, literally "damage that cannot be compensated," often implying irreparable or exceptionally severe harm) if the provisional disposition were to continue.

- The creditor's "preserved right" is of such a nature that its objective can be achieved through monetary compensation (金銭的補償可能性 - kinsen-teki hoshō kanōsei).

- "Independent Ground" vs. "Concurrent Grounds" Theory: Historically, there was debate among scholars and in lower courts whether both the debtor's extraordinary damage AND the monetary compensability of the creditor's right had to be present (the "concurrent grounds" view), or if either one, if sufficiently established, could suffice (the "independent ground" view). Legal scholarship generally favored the independent ground view.

- Traditionally, two main prongs were considered:

- Significance of the 1951 Supreme Court Ruling: This 1951 decision is highly significant because it was the first time the Supreme Court clearly endorsed the "independent ground" theory. It explicitly held that if the creditor's potential damages are monetarily compensable and the debtor provides adequate security, this factor alone can constitute a "special circumstance" justifying the revocation of the provisional disposition, without necessarily requiring proof of separate, extraordinary hardship on the debtor (though such hardship was also present in this case).

- Reflection in Current Law (CPRA Art. 39): The current CPRA Art. 39 reflects this understanding. It states that a provisional disposition can be revoked if "there are circumstances where continuing it would cause the debtor damage that cannot be compensated (irreparable harm) or other special circumstances exist." This wording explicitly acknowledges that "irreparable harm to the debtor" is one example of a special circumstance, but "other special circumstances" (which can include the monetary compensability of the creditor's interest) can also justify revocation, provided adequate security is furnished by the debtor.

- Holistic Assessment in Modern Practice: Despite the "independent ground" principle, modern practice under CPRA Art. 39 typically involves a comprehensive balancing of interests. Courts will consider the nature of the preserved right, the purpose of the provisional disposition, the extent of the creditor's potential damage if the order is revoked, the means available for the creditor's recovery, the hardship to the debtor if the order remains, and other relevant factors to arrive at an equitable decision. The court generally does not re-adjudicate the existence of the preserved right or the initial necessity of preservation when deciding on a CPRA Art. 39 revocation; rather, it focuses on whether the "special circumstances" now warrant lifting the order upon the provision of security. The system is also applicable to provisional dispositions that determine a provisional status (仮の地位を定める仮処分 - kari no chii o sadameru karishobun).

- Examples of "Special Circumstances":

- Debtor's Extraordinary Damage: This includes situations where continuing the provisional order would cause significant disruption to the debtor's business operations, lead to a substantial decrease in the value of the subject property, or cause extreme damage to the debtor's reputation or credit. The emphasis is on harm that is more severe than what a debtor might ordinarily expect from such a provisional measure, or where the balance of hardship clearly disfavors maintaining the order.

- Creditor's Harm Being Monetarily Compensable: This is often interpreted relatively strictly. It is more likely to be found where the ultimate objective of the creditor's preserved right is financial in nature (e.g., claims based on fraudulent conveyance, enforcement of security interests, or statutory reserved portions of an estate) or where the subject matter of the dispute is highly fungible (like publicly traded shares, where a monetary equivalent is readily available).

- Conversely, for unique assets like real estate involved in claims for specific performance or to prevent encroachment, or in cases involving intellectual property rights or provisional orders for wage payments, courts are often reluctant to find that the creditor's interest is adequately compensable by money alone, as the creditor typically seeks the specific thing or status, not just its monetary value.

- Application to the Construction Prohibition in this Case: Legal commentary suggests that under a very strict modern interpretation, a construction prohibition involving real estate (where the landowner Y claims rights to the land itself) might often be viewed as not being primarily compensable by money for the landowner. The landowner usually wants their land free of the unauthorized building, not just damages. However, the 1951 Supreme Court, in this specific case, affirmed the High Court's finding that Y's harm was monetarily compensable. It's also important that the High Court had concurrently noted the "great damage" X (the debtor) would suffer if the construction remained halted (rotting materials, liability to the contractor). The Supreme Court's own judgment emphasized that if the creditor's harm is determined to be monetarily compensable and security is posted, this can be sufficient for revocation. Thus, the outcome reflects a balancing of these considerations, with the security provided by X ensuring that Y's monetarily assessable damages would be covered.

Concluding Thoughts

The Supreme Court's 1951 decision in this construction prohibition case was a significant development in Japanese provisional remedy law. It established the important principle that if a creditor's potential harm from the lifting of a provisional disposition can be adequately compensated by money, and the debtor provides sufficient security for this purpose, this alone can constitute a "special circumstance" justifying the revocation of the provisional order. This allows courts to provide relief to debtors from potentially harsh provisional measures without needing to re-evaluate the underlying merits of the main dispute at that stage, provided the creditor's financial interests are secured.

While the legal landscape has evolved with the enactment of the Civil Provisional Remedies Act, which codifies the "special circumstances" revocation (Article 39) and generally calls for a comprehensive assessment of various factors, this early Supreme Court ruling remains a key precedent. It underscores the judiciary's role in balancing the competing interests of creditors seeking interim protection and debtors facing the burdens of such provisional restraints, and it provides a practical avenue for relief when monetary compensation can adequately address the creditor's primary concerns.