Balancing Duty and Danger: Japan's Supreme Court on Police Pursuits and Third-Party Harm

Date of Judgment: February 27, 1986

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench

Introduction

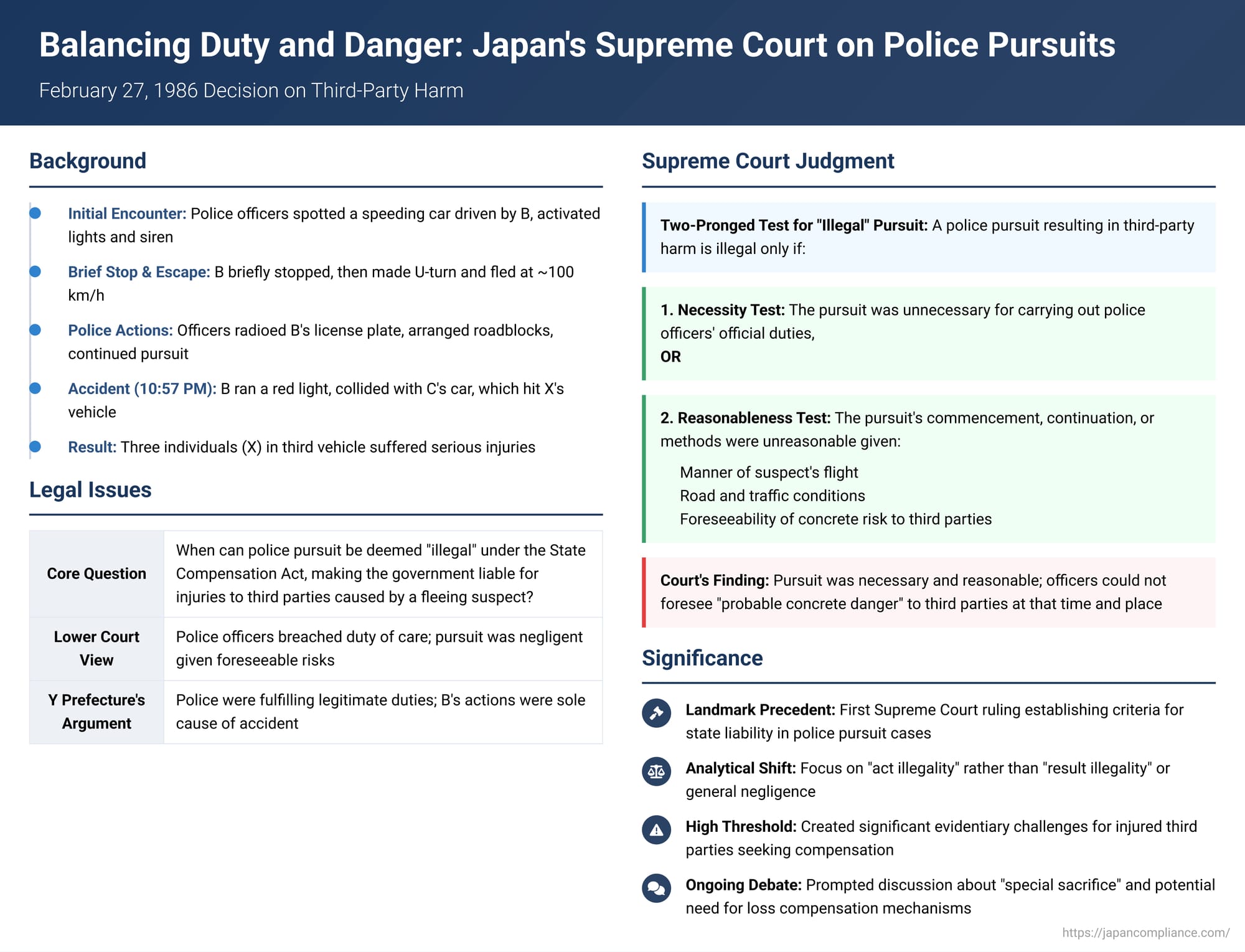

On February 27, 1986, the First Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan delivered a significant judgment in a case concerning state compensation liability for injuries sustained by innocent third parties as a result of a police vehicle pursuit. The core issue before the Court was to define the conditions under which the actions of police officers in pursuing a fleeing vehicle could be deemed "illegal," thereby triggering the state's responsibility to compensate for harm caused by the fleeing driver to bystanders. This decision, originating from Toyama Prefecture, became a leading precedent, establishing crucial criteria for assessing the legality of police pursuits, particularly emphasizing the necessity and reasonableness of the officers' conduct in the face of foreseeable risks.

I. The Fateful Chase: A Speeding Violation Escalates

The case arose from a sequence of events that began with a routine traffic violation and rapidly escalated into a high-speed chase culminating in a tragic accident.

The Initial Encounter and Pursuit:

At approximately 10:50 PM on May 29, 1975, police officers A, who were employees of Y Prefecture, were on a routine patrol in their designated police car. They observed a passenger car, driven by an individual later identified as B, committing a speeding violation. After confirming that B's speed exceeded the legal limit, the officers activated their patrol car's flashing red lights and siren and initiated a pursuit to stop B's vehicle.

Brief Stop and Renewed, High-Speed Flight:

B initially attempted to evade the pursuing police car but then briefly brought his vehicle to a stop. The police car also stopped, and during this interval, the officers managed to confirm and record B's vehicle license plate number. However, as officers A alighted from their patrol car with the intention of approaching B for questioning, B suddenly and unexpectedly executed a U-turn and sped off in the opposite direction, this time at a very high speed of approximately 100 kilometers per hour.

Pursuit Resumes with Backup Alerted:

Officers A immediately re-entered their patrol car and resumed the pursuit, again with their lights and siren activated to signal B to stop. Simultaneously, they used their police radio to transmit B's vehicle details (including the license plate number, car type, color, and direction of flight) to the prefectural police headquarters. This communication led to arrangements for police roadblocks to be established and alerts to be issued to other police units in the area. Officers A continued their direct pursuit, maintaining a high speed and a distance estimated at about 20 to 50 meters behind B's fleeing vehicle.

B's Continued Reckless Evasion:

B, the driver of the fleeing vehicle, continued his desperate attempt to escape at high speed (around 100 km/h). In doing so, he committed a series of further serious traffic violations, which included dangerously overtaking another vehicle by swerving into the oncoming traffic lane and running at least one red traffic signal at an intersection.

A Deceptive Lull and Re-escalation:

At one point during the chase, after making a left turn onto a different road, B's vehicle temporarily disappeared from the direct line of sight of the pursuing police car. Believing he might have successfully evaded the police, B briefly reduced his speed to approximately 70 km/h. However, the police car, having also navigated the turn, quickly began to close the distance again. Upon realizing that the police car was still in pursuit (likely by seeing its flashing lights in his rearview mirror once more), B re-accelerated his vehicle to approximately 100 km/h. He then proceeded to drive through a yellow flashing signal at one intersection and red flashing signals at two subsequent intersections without stopping or slowing adequately.

The Final Moments of the Pursuit and the Collision:

As B's vehicle entered a section of road that narrowed to a single lane in each direction and was approaching a right-hand curve, it once again went out of sight of the pursuing police car. At this critical juncture, the police officers in the patrol car decided to turn off their siren, although they kept the red emergency lights flashing. They also reduced their speed as they proceeded cautiously around the curve where B's car had disappeared.

Despite the police car having slowed and its siren being turned off, B continued his reckless flight. At approximately 10:57 PM, B drove his vehicle at high speed through a red traffic signal at a busy intersection. In doing so, B's car violently collided with another passenger car, driven by C, which was lawfully proceeding through the intersection on a green signal. The force of this initial collision caused C's car to be violently pushed into yet another vehicle. This third vehicle was carrying the plaintiffs, X (three individuals). As a direct result of this chain-reaction collision, the individuals in X's vehicle suffered serious injuries, including pelvic fractures.

The Lawsuit Against the Prefecture:

Following these events, X (the injured third parties) filed a lawsuit against Y Prefecture. They sought monetary damages, basing their claim on Article 1, paragraph 1 of Japan's State Compensation Act. Their central allegation was that the pursuit of B's vehicle by the prefectural police officers A was, under the circumstances, an illegal act, and that this illegal pursuit was a contributing cause of the accident and their resulting injuries.

II. Lower Court Rulings Favoring the Injured Third Parties

The case was first heard at the Toyama District Court and then proceeded to the Nagoya High Court (Kanazawa Branch) on appeal. Both of these lower courts found in favor of the injured plaintiffs, X, at least in part.

Toyama District Court (First Instance):

The District Court concluded that Y Prefecture was liable and ordered it to pay damages to X. The first instance court's decision focused significantly on the concept of negligence, specifically a breach of a duty of care, on the part of the pursuing police officers. The District Court reasoned that police officers engaged in traffic enforcement, including vehicle pursuits, have a duty to prevent traffic accidents if there is a foreseeable and concrete danger that their pursuit might cause the pursued vehicle to drive recklessly and thereby precipitate an accident harming third parties. The court suggested that the crucial decision of whether to continue or cease a pursuit should be based on a comprehensive and ongoing assessment of various factors. These factors include the speed and driving manner of the fleeing vehicle, the nature and severity of the initial offense for which the pursuit was initiated, the prevailing road and traffic conditions, and the availability (or lack thereof) of alternative means of apprehending the suspect. The commentary also intriguingly suggests that the first instance court might have been influenced in its finding of illegality by what is known as a "result illegality" (kekka fuhō) perspective. This perspective implies that the very severity of the harm ultimately suffered by the innocent third parties (X) could contribute to a finding that the police action leading to such a result was, in fact, illegal.

Nagoya High Court, Kanazawa Branch (Appeal):

Y Prefecture, dissatisfied with the District Court's ruling, appealed the decision to the Nagoya High Court (Kanazawa Branch). However, the High Court also found in favor of X, largely upholding the District Court's conclusion that the prefecture was liable for the damages sustained by the plaintiffs. It was this adverse decision from the High Court that Y Prefecture then appealed to the Supreme Court of Japan.

III. The Supreme Court's Reversal: Defining "Illegal Pursuit"

In a judgment that would become a significant precedent, the Supreme Court of Japan overturned the decisions of both lower courts and ruled in favor of Y Prefecture. The Court found that, based on the specific facts of the case, the police pursuit was not illegal under the State Compensation Act.

A. The Duties and Powers of Police Officers in Pursuing Suspects

The Supreme Court began its legal analysis by affirming the fundamental duties and powers vested in police officers under Japanese law.

- It stated that police officers are charged with the responsibility of stopping and questioning individuals whom they reasonably suspect of having committed some form of crime, based on their observation of unusual behavior or other relevant surrounding circumstances.

- Furthermore, officers have a clear duty to promptly apprehend or arrest persons whom they witness committing an offense (i.e., caught in flagrante delicto). These fundamental duties are grounded in enabling statutes such as the Police Act (specifically Articles 2 and 65) and the Police Duties Execution Act (Article 2, paragraph 1).

- Flowing from these duties, the Court recognized that pursuing suspects, including by vehicle, for the purpose of fulfilling these responsibilities is a permissible and often necessary police function.

B. The Standard for Deeming a Police Pursuit "Illegal" When Third Parties are Harmed

The most critical aspect of the Supreme Court's judgment was its articulation of the specific legal criteria that must be met for a police pursuit to be deemed "illegal" for the purposes of imposing state compensation liability when an innocent third party is injured as a result of the actions of the fleeing vehicle (not directly by the police vehicle).

- The Court established a two-pronged test. A police pursuit resulting in such third-party harm is to be considered illegal if, and only if:

- The pursuit was unnecessary for the police officers to carry out their mandated official duties (e.g., apprehending an offender, questioning a legitimately suspicious person), OR

- The commencement of the pursuit, its continuation, or the specific methods employed during the pursuit were unreasonable (or "improper" - fusōtō) when evaluated in light of all relevant circumstances. These circumstances include:

- The manner and characteristics of the suspect vehicle's flight (e.g., its speed, the degree of recklessness displayed by the driver).

- The prevailing road and traffic conditions at the time and location of the pursuit.

- Critically, the specific nature and the degree of foreseeability of the concrete risk of harm to third parties that could reasonably be anticipated from these combined factors.

C. Application of the Standard to the Facts of This Specific Case

The Supreme Court then meticulously applied its newly articulated two-pronged standard to the detailed facts of the pursuit of B's vehicle by officers A:

- Was the Pursuit "Unnecessary"?

- The Court found that B was not merely a simple speeding offender. His subsequent actions—initially fleeing from the police, then briefly stopping, and then suddenly executing a U-turn and fleeing again at extremely high speed when approached by the officers—constituted highly "suspicious behavior". This pattern of behavior, the Court reasoned, gave the officers legitimate grounds to suspect that B might be involved in some other, potentially more serious, criminal activity beyond the initial speeding violation.

- Therefore, the police officers had a legitimate and pressing need not only to apprehend B for the flagrant traffic offense (as a person caught in the act) but also to question him regarding his highly suspicious and evasive conduct.

- The Court took into account the fact that the officers had managed to note B's license plate number, had radioed this information to police headquarters, and were aware that a police checkpoint was in the process of being set up to intercept B. However, it reasoned that the driver's identity was still unknown at that point, and that even with such measures in place, direct pursuit is often ultimately necessary to effectively apprehend a determinedly fleeing vehicle. Consequently, the Supreme Court concluded that the pursuit was indeed necessary for the police officers to properly fulfill their law enforcement duties.

- Was the Pursuit "Unreasonable" (in its commencement, continuation, or method)?

- Road and Traffic Conditions: The Court considered the environment of the pursuit. It noted that the roads on which the chase primarily occurred, while having shops and houses alongside them and featuring numerous intersections, were not characterized by exceptionally dangerous or restrictive traffic conditions. The roads were described as being four-lane initially, later narrowing to two lanes but still including sidewalks, and the overall road width was approximately 12 meters.

- Time of Day: The incident took place late at night, around 11:00 PM. The Court likely considered that traffic volume would generally be significantly lighter at this hour compared to daytime.

- Foreseeability of Harm to Third Parties: Taking into account these road and traffic conditions, the late hour, and the observed manner of B's driving (which, while clearly reckless, was part of an ongoing evasion), the Supreme Court concluded that the pursuing police officers could not, at that particular time and under those specific circumstances, have foreseen a "probable concrete danger" of harm to third parties that would arise specifically as a result of their continued pursuit.

- Method of Pursuit Employed by Police: The Court also examined the specific methods used by the police officers during the pursuit. This included their use of the patrol car with flashing emergency lights and siren (and their later decision to turn off the siren and reduce speed when they temporarily lost sight of B's vehicle around a curve). The Supreme Court found that these methods, in themselves, did not involve any actions that were particularly dangerous or unreasonable on the part of the police.

- Supreme Court's Conclusion on Legality: Based on this detailed application of its two-pronged test, the Supreme Court concluded that the police officers' pursuit of B's vehicle did not meet the criteria for illegality under Article 1 of the State Compensation Act. The pursuit was found to be neither "unnecessary" for the performance of their duties nor "unreasonable" in its execution given the totality of the circumstances and the degree of foreseeable risk at the time. Therefore, the Court held, there was no "illegal" act committed by the police officers that could ground a claim for state compensation by the injured third parties, X. The judgments of the lower courts were, consequently, reversed.

IV. Legal Commentary and Broader Implications

This 1986 Supreme Court decision, being the first of its kind on this specific issue, has generated considerable legal commentary and carries significant broader implications.

A Seminal Ruling on Police Pursuits and State Liability:

- This judgment is recognized as a landmark because it was the first time Japan's highest court specifically addressed and laid down the criteria for determining state compensation liability when innocent third parties are injured as an indirect consequence of police vehicle pursuits. As such, it established an important legal precedent that would guide lower courts in similar future cases.

The Shift in Analytical Framework from Negligence to "Illegality of the Pursuit Act":

- The Supreme Court's analytical framework points out that many prior lower court decisions in cases involving harm from police actions had tended to focus their analysis on whether the individual police officers involved were negligent—that is, whether they had breached a general duty of care (e.g., to prevent accidents). This often involved a detailed, fact-intensive examination of what the officers should have foreseen and whether they should have acted differently, for example, by ceasing the pursuit. The first instance court in this very case had largely followed that more traditional negligence-focused approach.

- The Supreme Court, however, framed its decisive test more directly around the "illegality" (ihōsei) of the pursuit act itself, when considered as an official act performed in the exercise of public power. The central question became whether the pursuit, as a whole or in its specific aspects, was either "unnecessary" or "unreasonable" to the point of being unlawful under the State Compensation Act. This approach is viewed by legal commentators as a subtle but important shift towards an "act illegality" (kōi fuhō) theory. Under this theory, the primary focus is on the intrinsic lawfulness or unlawfulness of the governmental conduct itself, rather than predominantly on a "result illegality" (kekka fuhō) theory, where the negative outcome or the severity of the harm suffered might disproportionately influence the determination of whether the antecedent act was illegal.

The Absence of Specific Laws Authorizing Harm to Third Parties During Pursuits:

- An important underlying legal reality, as implicitly acknowledged by the courts, is that while police officers are clearly authorized by law to pursue suspects (e.g., under the Police Act and the Police Duties Execution Act), no specific statute explicitly permits them to cause harm to innocent third parties as a collateral consequence of such pursuits. The harm suffered by X in this case was a non-purposive and non-typical (i.e., not an intended or direct) outcome of the police action of pursuit. The first instance court had grappled with this tension, acknowledging that the pursuit might be considered "lawful" from the perspective of apprehending the fleeing suspect, B, but could still be deemed problematic and potentially illegal in relation to the injured third party, X, if the harm to X was not an unavoidable consequence of an otherwise justified and proportionate action, and particularly if the public interest served by continuing the pursuit did not clearly outweigh the risk or actuality of harm to X.

Defining the Scope of Official Duty Under the State Compensation Act:

- The Supreme Court's specific criteria for determining illegality—that the pursuit must be either "unnecessary" or "unreasonable" in its commencement, continuation, or method—can be understood as defining the scope of the official duties of police officers for the purposes of Article 1 of the State Compensation Act. Specifically, these criteria imply that police officers have a duty to conduct pursuits in a manner that avoids unnecessary endangerment to the public, a duty that must be carefully balanced against their primary and coexisting duty to enforce the law and apprehend offenders. The precise wording used by the Supreme Court, focusing on when "the said pursuit act is illegal," clearly points towards defining what constitutes a breach of this complex set of official duties under the Act.

The "Danger Avoidance Duty" (kiken kaihi gimu) and Differential Risk Assessment:

- The concept of a "danger avoidance duty", is a broad one that applies in relation to both the fleeing suspect (whose actions are creating danger) and any innocent third parties who might be inadvertently endangered by the pursuit itself. However, the commentary also posits that the ultimate assessment of responsibility or liability might differ between these two categories of individuals. This is because the fleeing suspect is an active agent who contributes significantly, often primarily, to the creation and escalation of the dangerous situation. In contrast, an innocent third party is merely an unfortunate victim of circumstances, caught in the path of a danger not of their making. This distinction in causal contribution and culpability could influence how a court weighs the factors in determining liability.

Significant Challenges for Third-Party Victims Seeking Compensation:

- The legal standard established by the Supreme Court in this 1986 case—requiring a plaintiff to prove either that the police pursuit was "unnecessary" or that its specific conduct was "unreasonable" given the foreseeable "probable concrete danger" of harm to third parties—can present a high evidentiary bar for victims to meet. Proving what police officers could or should have reasonably foreseen in the rapidly evolving, high-stress, and often chaotic environment of a high-speed vehicle pursuit is inherently difficult. If the police pursuit is ultimately deemed lawful under this stringent standard, and if the fleeing driver who directly caused the accident is uninsured, unidentifiable, or otherwise financially unable to provide adequate compensation (i.e., is "judgment-proof"), innocent third-party victims can be left with insufficient or no redress despite suffering serious harm through no fault of their own.

The Unresolved Question of "Special Sacrifice" and the Potential for Loss Compensation:

- This potential for uncompensated harm to innocent third parties, even when police actions are deemed lawful, has led to important discussions within Japanese legal scholarship. If a lawful and properly conducted police pursuit nevertheless results in unavoidable and serious harm to an innocent bystander, and that victim cannot obtain full compensation from the direct tortfeasor (the fleeing driver), it raises a profound question of fairness: does this situation constitute a "special sacrifice" made by an individual for the benefit of the broader public good (i.e., the effective enforcement of laws and the apprehension of offenders)? The commentary notes that some legal scholars in Japan have proposed legislative reforms, such as amending existing laws like the Act Concerning Benefits for Persons Who Suffer Injury in Cooperating with Police Duties, or drawing analogies from certain foreign legal systems that provide for specific compensation to innocent victims of lawful police actions (for example, individuals accidentally injured by police gunfire during a legitimate operation). The aim of such proposals would be to create a system of "loss compensation" (sonshitsu hoshō) for these innocent third parties who are harmed during otherwise lawful police pursuits. Such a system would be distinct from state compensation for illegal acts and would operate on the principle that when lawful and necessary state actions nonetheless impose disproportionate and severe burdens on specific innocent individuals, society as a whole should bear or at least share the cost of that sacrifice.

V. Conclusion

The Supreme Court of Japan's February 27, 1986, decision in this case involving third-party injuries during a police pursuit established critical legal benchmarks for determining state liability under such challenging circumstances. By focusing its criteria on whether the police pursuit was "unnecessary" for the fulfillment of official duties or "unreasonable" in its execution given the totality of circumstances including foreseeable risks, the Court set a standard that endeavors to balance the police's imperative duty to enforce the law and apprehend offenders with the equally important need to protect the safety of the general public.

While this ruling provided much-needed clarity and a framework for analyzing such cases, it also starkly highlighted the significant evidentiary and legal challenges faced by innocent third-party victims seeking compensation when police conduct is ultimately deemed lawful. The decision continues to underscore an ongoing and important legal and societal debate in Japan regarding how best to ensure adequate and fair redress for those who suffer harm as an indirect, though sometimes devastating, consequence of necessary law enforcement activities, particularly when the direct wrongdoer (the fleeing suspect) is unable to provide compensation. The questions it raises about "special sacrifice" and the potential need for dedicated loss compensation mechanisms remain pertinent to discussions about justice and fairness in a society that relies on effective policing.