Green Deals & Antitrust in Japan: How to Structure Decarbonisation Cooperation

TL;DR

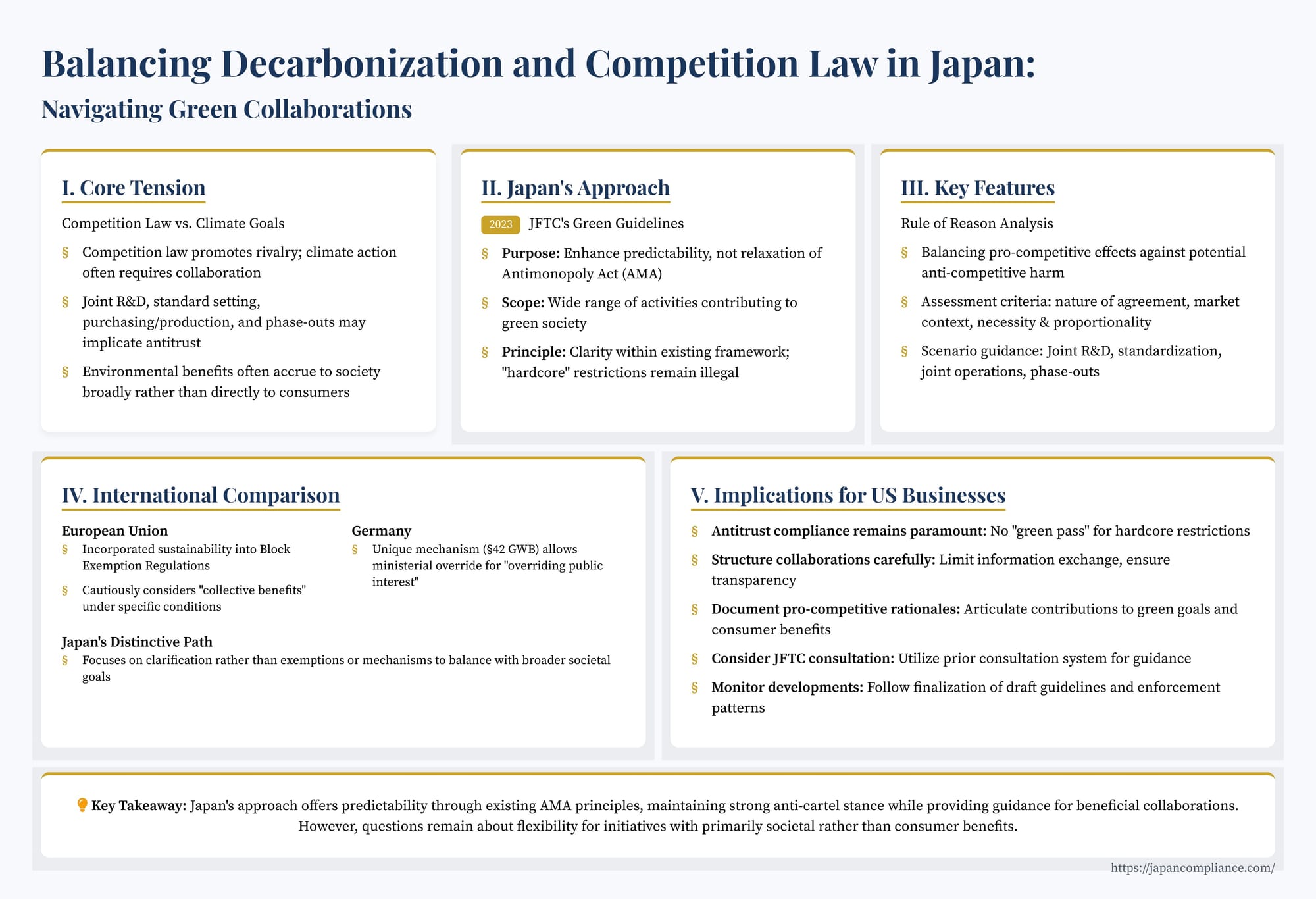

- Japan’s 2050-carbon-neutral goal drives unprecedented cooperation, yet the Antimonopoly Act still bans hardcore cartels.

- JFTC’s draft “Green Guidelines” clarify that most sustainability alliances face the usual rule-of-reason test: necessity, proportionality, and consumer impact.

- No blanket green exemption exists—firms must structure joint R&D, purchasing, standards or phase-outs to minimise competitive harm and may seek JFTC prior consultation.

- US companies can collaborate in Japan, but need robust antitrust safeguards, clear pro-competitive rationales, and careful information-sharing protocols.

Table of Contents

- The Core Tension: Sustainability vs Competition Law

- International Approaches: EU & Germany

- Japan’s Approach: Clarification, Not Relaxation

- Analysis and Comparison

- Implications for US Businesses Collaborating in Japan

- Conclusion

The global imperative to achieve climate goals, including Japan's commitment to carbon neutrality by 2050, necessitates profound industrial transformation. Developing green technologies, establishing sustainable supply chains, and phasing out high-emission processes often require unprecedented levels of investment and, frequently, collaboration between companies—sometimes even direct competitors. This push for collaboration, however, creates inherent tension with competition law principles designed primarily to foster rivalry and prevent collusion that could harm consumer welfare through higher prices or reduced output and innovation.

How is Japan navigating this complex intersection? As businesses increasingly explore joint initiatives to accelerate decarbonization, understanding the application of Japan's Antimonopoly Act (AMA) to these "green collaborations" is critical. Recent developments, including draft guidelines from the Japan Fair Trade Commission (JFTC), suggest Japan is forging a path focused on clarifying existing rules rather than creating broad exemptions, presenting both predictability and potential limitations for businesses.

The Core Tension: Sustainability Goals vs. Competition Law Principles

Competition law, at its core, aims to protect the competitive process, believing that rivalry between firms leads to lower prices, better quality, greater choice, and more innovation, ultimately benefiting consumers. Agreements between competitors that restrict this rivalry—such as fixing prices, limiting production, dividing markets, or jointly refusing to deal—are typically viewed with suspicion and often prohibited outright (as "hardcore cartels").

However, many initiatives vital for achieving ambitious climate targets might involve precisely such inter-firm cooperation:

- Joint Research & Development: Pooling resources to develop breakthrough low-carbon technologies.

- Standard Setting: Agreeing on common standards for energy efficiency, emissions measurement, or sustainable materials.

- Joint Purchasing/Production/Logistics: Collaborating to achieve economies of scale in sourcing renewable energy, producing green hydrogen, or optimizing low-emission transportation.

- Phase-Out Agreements: Jointly agreeing to discontinue polluting products or processes ahead of regulatory mandates.

While potentially beneficial for the environment, these collaborations could, depending on their structure and market context, reduce competitive pressures, facilitate the exchange of sensitive information leading to price coordination, limit technological choices, or foreclose opportunities for non-participating firms.

A further challenge lies in the nature of environmental benefits. The positive impacts of reduced emissions often accrue broadly to society as a whole (a positive externality), rather than directly translating into lower prices or improved quality for the immediate consumers of a specific product. Traditional competition law analysis, heavily focused on consumer welfare within a defined market, can struggle to adequately weigh these diffuse societal benefits against potential localized competitive harm.

International Approaches: A Brief Context

Jurisdictions globally are grappling with this issue, with varying approaches emerging:

- European Union: The European Commission has incorporated sustainability considerations into its revised Horizontal and Vertical Block Exemption Regulations and Guidelines. While maintaining a primary focus on consumer welfare, the framework allows for certain "sustainability agreements" to be exempted under Article 101(3) TFEU if they generate benefits that outweigh competitive restrictions. Notably, it cautiously opens the door to considering "collective benefits" (societal environmental gains) under specific conditions, particularly if consumers within the relevant market also substantially benefit, even indirectly. However, the extent and methodology for weighing these broader benefits remain subjects of ongoing debate.

- Germany: Germany's competition law includes a unique mechanism (§42 GWB) allowing a government minister (for Economic Affairs and Climate Action) to authorize a merger previously blocked by the Federal Cartel Office on competition grounds if it is justified by an "overriding public interest." This tool has been invoked, albeit rarely and controversially, in ways that touch upon sustainability, such as justifying a merger based on its contribution to the energy transition (e.g., the Miba/Zollern case involving components for wind turbines). This represents a potential, though exceptional, override of competition concerns for broader policy goals.

Japan's Approach: Clarification, Not Relaxation

In contrast to potentially creating new exemptions or mechanisms that explicitly balance competition against broader societal goals, Japan's approach, spearheaded by the JFTC, has focused primarily on clarifying how existing Antimonopoly Act principles apply to collaborations aimed at achieving a green society.

Following policy discussions and recommendations, the JFTC established a study group and, in January 2023, released draft "Antimonopoly Act Guidelines Concerning Business Activities, etc. Toward the Realization of a Green Society" (グリーン社会の実現に向けた事業者等の活動に関する独占禁止法上の考え方) for public comment (final version anticipated later).

Key Features of the JFTC's Draft Green Guidelines:

- Purpose: The stated goal is not to relax the AMA or create green exemptions, but to enhance predictability for businesses. By clarifying how collaborations related to decarbonization and other green initiatives will be assessed under existing law, the JFTC aims to prevent companies from being unduly deterred from potentially pro-competitive or competitively neutral green collaborations due to legal uncertainty.

- Scope: The guidelines cover a wide range of potential business activities contributing to a green society, encompassing joint efforts in technology development, energy use, resource procurement, manufacturing, logistics, and sales. While prompted by climate change concerns, the underlying principles appear applicable to collaborations pursuing other environmental or potentially broader sustainability/SDG objectives.

- Reiteration of Core AMA Principles: The guidelines firmly reiterate that agreements constituting "hardcore" restrictions of competition – such as price fixing, output restrictions, market allocation, or bid rigging – remain illegal under the AMA, even if pursued under the banner of sustainability. Green objectives cannot justify cartel conduct.

- Rule of Reason Analysis for Other Collaborations: For collaborations that do not amount to hardcore restrictions, the guidelines indicate a "rule of reason" approach. This involves balancing the potential pro-competitive effects and benefits against the potential anti-competitive effects. The assessment considers:

- Nature of the Agreement: What is the specific purpose and mechanism of the collaboration? What information is exchanged? Are restrictions limited to what is necessary to achieve the green objective?

- Market Context: What are the market shares of the participating companies? What is the overall market structure?

- Potential Anti-competitive Effects: Does the collaboration significantly reduce price, quality, or innovation competition? Does it raise barriers to entry for others? Does it increase the risk of collusion?

- Potential Pro-competitive Effects/Justifications: Does the collaboration lead to significant efficiencies, promote the development or diffusion of green technologies, enable risk-sharing for necessary investments, or help achieve environmental standards more quickly or effectively? Does it benefit consumers (directly or indirectly)?

- Necessity and Proportionality: Is the collaboration reasonably necessary to achieve the stated green objective? Could the objective be achieved through less anti-competitive means?

- Specific Scenarios Discussed: The draft guidelines provide illustrative examples across various areas:

- Joint R&D: Generally viewed favorably if focused on pre-competitive research, but requires caution regarding information exchange and impacts on independent innovation paths.

- Standardization: Setting environmental or efficiency standards can be pro-competitive by facilitating market entry and comparability, provided the process is open, transparent, non-discriminatory, and doesn't stifle innovation or become a cover for collusion.

- Joint Purchasing/Production/Logistics: Assessed based on market shares and potential impacts on input costs, output levels, and downstream competition. Joint purchasing of renewable energy or joint investment in low-carbon infrastructure might be permissible if competitive harm is unlikely.

- Information Exchange: Sharing aggregated, historical, or publicly available environmental data is generally low risk. Sharing competitively sensitive information (prices, costs, output plans, future R&D) carries high risk, even in a green context.

- Phase-Outs: Joint agreements to withdraw environmentally harmful products might be justifiable if they don't restrict competition on remaining products and are necessary for the transition, but require careful assessment.

- Encouragement of Consultation: The JFTC explicitly encourages businesses planning significant green collaborations with potential antitrust implications to utilize its prior consultation system to obtain guidance on the specific plan's legality under the AMA.

Analysis and Comparison

Japan's "clarification" approach contrasts with developments elsewhere. The EU is grappling with how to integrate potentially non-consumer welfare benefits (collective environmental gains) into its exemption framework, representing a cautious evolution of its doctrine. Germany retains a mechanism, however exceptional, for political override based on public interest.

Pros of Japan's Approach:

- Legal Certainty (within limits): By grounding the analysis in existing AMA principles, the guidelines aim to provide a degree of predictability based on established legal frameworks.

- Strong Anti-Cartel Stance: It clearly maintains that environmental goals cannot excuse hardcore restrictions like price fixing.

- Avoiding Politicization: It keeps the assessment largely within the technical expertise of the competition authority, potentially avoiding concerns (raised by economists like Jean Tirole) about independent agencies taking on broader, potentially political, mandates that could compromise their core mission and independence.

Cons/Challenges of Japan's Approach:

- Flexibility Limits: A strict focus on existing principles, largely centered on market impacts and consumer welfare, might be less accommodating for collaborations where the primary benefits are diffuse environmental gains rather than direct consumer price/quality improvements, even if those collaborations are necessary for significant decarbonization leaps.

- Weighing Green Benefits: The guidelines don't establish a clear methodology for how positive environmental impacts or contributions to national climate goals should be weighed against potential competitive restrictions within the rule-of-reason analysis. This remains an area of uncertainty.

- Potential Deterrence: Some argue that without clearer safe harbors or a more explicit recognition of environmental benefits as a justification, businesses might still be overly cautious and refrain from pursuing potentially valuable green collaborations due to lingering antitrust risks.

Implications for US Businesses Collaborating in Japan

For US companies considering or involved in sustainability-focused collaborations with Japanese partners or competitors in the Japanese market, the JFTC's approach has several practical implications:

- Antitrust Compliance is Paramount: Sustainability objectives do not provide a "green pass" to ignore the AMA. Agreements involving price fixing, market sharing, output limits, or bid rigging remain illegal per se.

- Structure Collaborations Carefully: Design joint initiatives to minimize anti-competitive potential.

- Limit information exchange strictly to what is necessary for the collaboration's green objective; avoid sharing current or future pricing, costs, output, or specific R&D plans.

- If setting standards, ensure the process is transparent, non-discriminatory, allows for innovation, and participation is reasonably open.

- If joint production or purchasing involves significant market shares, carefully assess potential impacts on input/output markets and downstream competition.

- Focus on Pro-competitive Rationale: For collaborations assessed under the rule of reason, clearly articulate and document the pro-competitive justifications and efficiencies. This should include how the collaboration contributes to green goals and, where possible, how it might ultimately benefit consumers (e.g., through faster innovation, lower long-term costs, improved product quality/choice). Demonstrate why the collaboration is necessary and the chosen method is the least restrictive option to achieve the environmental objective.

- Consider JFTC Consultation: For novel, large-scale, or potentially borderline collaborations, proactively engaging with the JFTC through its consultation mechanism can provide valuable guidance and significantly reduce legal uncertainty before committing significant resources.

- Monitor Guideline Finalization and Enforcement: The JFTC's Green Guidelines were in draft form as of early 2023. Businesses should monitor the final version and subsequent JFTC enforcement actions or case law to understand how these principles are applied in practice. International developments, particularly in the EU, may also continue to influence Japanese thinking.

Conclusion

Japan is actively addressing the critical intersection of decarbonization and competition policy. Its chosen path, emphasizing clarification of the existing Antimonopoly Act through detailed guidelines rather than creating broad exemptions, aims to provide legal predictability while maintaining a strong stance against anti-competitive collusion. While this approach offers a degree of certainty, questions remain about its flexibility in accommodating collaborations whose primary benefits are societal rather than directly consumer-focused. For businesses, particularly foreign companies engaging in green initiatives in Japan, this means that while collaboration is possible and encouraged in principle, it must be structured with careful attention to AMA compliance. Demonstrating pro-competitive rationales, minimizing restrictive elements, and potentially seeking prior consultation with the JFTC will be key strategies for successfully navigating this evolving legal landscape and contributing to Japan's ambitious climate goals without falling foul of competition law.

- Understanding Exclusionary Practices Under Japan’s Antimonopoly Act

- Playing a Leading Role? Japan’s Antitrust Surcharge Enhancements for Cartel Facilitators

- Japan Targets Mobile Ecosystems: Inside the Smartphone Software Competition Promotion Act

- JFTC – Draft Green Guidelines (2023 公表)

- METI – Green Growth Strategy Through Achieving Carbon Neutrality

- MOE – Roadmap to Beyond-Zero Carbon (Japanese)