Balancing Business and Public Good: Standing to Sue Over Waste Management Permits in Japan

Judgment Date: January 28, 2014, Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench

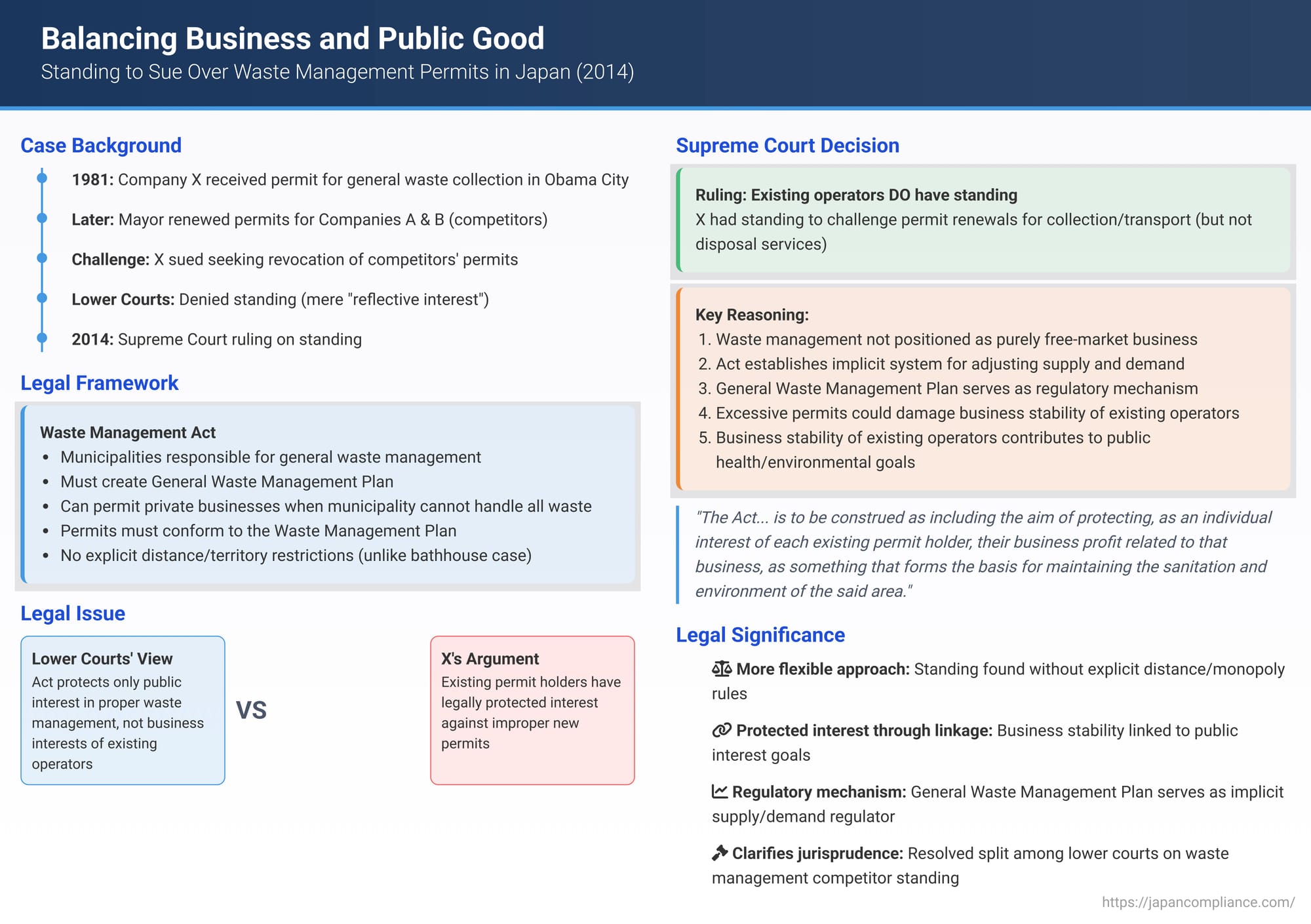

The business of waste management is crucial for public health and environmental protection. In Japan, general waste collection and disposal are primarily the responsibility of municipalities, but they can permit private companies to undertake these services. This raises a common issue in regulated industries: if a municipality grants or renews a permit for a new or existing waste management company, can an established competitor already operating in the area legally challenge that decision? A 2014 Supreme Court decision addressed this question of "plaintiff standing" for incumbent operators in the general waste management sector, offering a nuanced interpretation of how existing laws protect their business interests.

The Waste Management Permit System in Japan

The Waste Management and Public Cleansing Act (廃棄物の処理及び清掃に関する法律 - Haiki-butsu no Shori oyobi Seisō ni Kansuru Hōritsu, commonly referred to as the Waste Management Act or Haiki-butsu Shori Hō) governs the disposal and cleaning of waste in Japan. Under this Act (specifically Article 7, Paragraph 1, as it stood before a 1991 amendment, though the core principles discussed remain relevant), municipalities are responsible for the proper processing of general waste within their jurisdictions. They are required to formulate a General Waste Management Plan (一般廃棄物処理計画 - ippan haiki-butsu shori keikaku) that outlines, among other things, the projected volume of waste and the entities responsible for its collection and disposal.

While municipalities can carry out these services themselves, they are also empowered to grant permits to private businesses to conduct general waste collection and transport, as well as disposal services, particularly when it is difficult for the municipality to handle all waste processing on its own. A key requirement for granting or renewing such a permit is that the applicant's proposed operations must conform to the municipality's General Waste Management Plan (Article 7, Paragraph 5, Item 2 of the Act).

The Obama City Waste Permit Dispute: Facts of the Case

The plaintiff, X, was a company that had held a permit from the Mayor of Obama City in Fukui Prefecture since April 1981, allowing it to conduct general waste collection and transport services throughout the entire city. This permit had been renewed multiple times.

Subsequently, the Mayor of Obama City granted permit renewal dispositions to two other companies: Company A (for general waste collection and transport) and Company B (for general waste collection, transport, and disposal). X believed that these permit renewals granted to its competitors, A and B, were illegal. X filed a lawsuit against Y (Obama City) seeking the revocation of these permit renewals and also claimed damages under the State Redress Act.

The central issue before the Supreme Court, concerning the revocation claim, was whether X, as an existing permit holder, had the legal standing (原告適格 - genkoku tekkaku) to challenge the permit renewals granted to its competitors.

The Fukui District Court (First Instance) and the Nagoya High Court, Kanazawa Branch (Second Instance) both denied X plaintiff standing for the revocation suit. They ruled that the Waste Management Act was not intended to protect the individual business interests of existing operators, and therefore any economic impact X might suffer from increased competition was merely a "reflective interest" (反射的利益 - hanshateki rieki) rather than a legally protected individual interest. X then filed a petition for acceptance of final appeal with the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decision (January 28, 2014): Recognizing Standing for Existing Operators

The Supreme Court, Third Petty Bench, partially overturned the lower courts' decisions. It found that X did have plaintiff standing to challenge the permit renewals concerning general waste collection and transport granted to Companies A and B. (The part of the claim related to Company B's disposal permit was handled differently as X did not hold a disposal permit itself, and its appeal on that specific point was dismissed.) The case was remanded for further proceedings on the merits of the collection/transport permit challenge.

The Court's reasoning for affirming standing was as follows, drawing on the established criteria for "legally protected interest" as articulated in prior cases like the 2005 Odakyu Line judgment:

I. The Waste Management Act's Implicit System for Adjusting Supply and Demand

The Court began by acknowledging that if existing permit holders are already properly processing general waste and the municipality's General Waste Management Plan is based on this existing capacity, the mayor can refuse a new permit application if it's deemed that continuing with only the existing operators is appropriate for ensuring stable and proper waste management, and if the new application doesn't conform to the plan. This referenced an earlier 2004 Supreme Court decision.

The Court stated: "Thus, even when a municipality grants a permit to a party other than itself to conduct the business, it can be said that a mechanism is established to adjust the supply and demand situation in the general waste management business, through the mayor's judgment regarding permit requirements such as conformity with the General Waste Management Plan, so that the proper operation of the business is not harmed by excessive establishment of permit holders, etc."

Furthermore, the fact that permits are granted for specific areas within a municipality (Waste Management Act Art. 7(11)) indicates that this supply-demand adjustment is intended to operate within those defined zones.

II. General Waste Management Not a Purely Free-Market Business

The Court then emphasized the special nature of general waste management:

- Municipalities are only allowed to permit private operators when it is difficult for the municipality itself to handle waste processing. This is because general waste management is "fundamentally a business that municipalities should carry out themselves under their own responsibility".

- Proper processing is required based on the volume of waste generated within a given area, under a system of supply-demand adjustment.

- Considering these factors, "general waste management business under the Waste Management Act is not positioned as a business to be entrusted solely to free competition".

III. Potential Harm to Existing Operators and Public Interest

The Court then linked the protection of existing operators to the broader public interest:

"If, in a situation where a person has already received a permit or renewal for general waste management business for a certain area from the mayor, a permit or renewal for general waste management business granted to another person for the same area lacks appropriate consideration for the balance of supply and demand in that area and the impact of its fluctuation on the business of the existing permit holder, it can be said that an excessive establishment of permit holders will damage the balance of supply and demand, worsen their business management, and harm the proper operation of the business. This, in turn, could lead to a deterioration of sanitation and the environment in the said area, and further, to a certain extent, pose a risk of harm or impact to the health and living environment of the residents in that area."

IV. Conclusion: The Act Protects Existing Operators' Business Interests as Individual Interests

Synthesizing these points, the Supreme Court concluded:

"Considering comprehensively the mechanism and content of the regulations related to adjusting the supply and demand situation for general waste management business as described above, the purpose and objective of the Waste Management Act concerning such regulation, the nature of the general waste management business, and the nature and content of the permits related to that business, it should be said that the Waste Management Act, in order to prevent the aforementioned situation where the balance of supply and demand in the said area is damaged and the proper operation of the business is harmed, thereby leading to [negative consequences for sanitation and environment], establishes the said regulations for permit holders who conduct this business on behalf of the municipality after receiving a permit or renewal for general waste management business for a certain area from the mayor. The Act, through the mayor's judgment on whether to grant or refuse an application for a permit or renewal for general waste management business from another person, by considering the impact on the business of existing permit holders as described above, is to be construed as including the aim of protecting, as an individual interest of each existing permit holder, their business profit related to that business, as something that forms the basis for maintaining the sanitation and environment of the said area."

Therefore, "a person who has already received a permit or renewal for general waste management business under Article 7 of the Waste Management Act for a certain area has plaintiff standing as a person having a legal interest to seek the revocation of a general waste management business permit disposition or permit renewal disposition granted to another person for the said area".

Significance and Analysis

This 2014 Supreme Court decision is significant for its nuanced approach to competitor standing in a regulated industry where explicit statutory provisions for protecting existing businesses from competition are not overt.

1. Finding "Legally Protected Interest" Without Explicit Distance or Monopoly Rules

Previous Supreme Court cases on competitor standing, such as the 1962 Public Bathhouse case (see Hyakusen II, No. 164), often relied on the presence of "proper arrangement" regulations (like distance requirements between businesses) to infer a legislative intent to protect existing operators from excessive competition. In contrast, the Waste Management Act does not contain such explicit distance or territorial monopoly provisions for permit holders in the same direct manner.

Despite this, the Supreme Court in this case found a "legally protected interest" for existing general waste collection and transport operators. It did so by:

- Emphasizing the public service nature of general waste management, which is fundamentally a municipal responsibility.

- Highlighting the General Waste Management Plan as a tool for ensuring orderly service delivery, which implicitly involves considerations of supply and demand and the capacity of existing operators.

- Reasoning that the proper and stable operation of existing permit holders is essential for achieving the Act's ultimate public interest goals (environmental protection and public health). If existing, competent businesses are driven out by poorly considered new permits leading to excessive competition and financial instability, the public interest itself suffers.

- Therefore, the Act, by requiring permits to align with the overall plan and by aiming to ensure stable service, was interpreted as indirectly but intentionally protecting the legitimate business interests of those existing operators who are fulfilling their role in the municipal plan. Their business interest becomes an "individual interest" because its protection is instrumental to achieving the broader public good.

This is a more purposive and functional interpretation than one based solely on finding explicit "existing business protection" clauses.

2. The Role of the General Waste Management Plan

The General Waste Management Plan, which municipalities are required to create, played a key role in the Court's reasoning. By requiring permit applications to conform to this plan, and by recognizing that the plan itself is based on existing capacities and projected needs, the Court found an implicit mechanism for supply-demand adjustment. This mechanism, in turn, was seen as providing a basis for protecting the operational stability of existing, compliant permit holders.

3. Distinguishing from Purely Free-Market Competition

The Court explicitly stated that general waste management under the Act is "not positioned as a business to be entrusted solely to free competition". This acknowledgment of the regulated, public-service character of the industry was crucial for distinguishing it from sectors where open competition is the norm and where existing businesses typically have no legally protected interest against new entrants.

4. Impact on Lower Court Practice

This decision was noteworthy because it went against a trend in lower court rulings which had often denied standing to existing waste management businesses challenging new permits under the Waste Management Act precisely because the Act lacked explicit provisions like distance restrictions found in, for example, the Public Bathhouse Act. The Supreme Court's more flexible, purposive interpretation provided new guidance.

5. Broader Implications for Competitor Standing

While the specifics relate to waste management, the judgment's methodology – looking at the overall regulatory scheme, the public service nature of the regulated activity, and how the protection of incumbent operators might be instrumental to achieving broader public interest goals – could have implications for competitor standing in other regulated industries where explicit "existing business protection" clauses are absent, but where orderly service provision and public interest are paramount.

The PDF commentary also raises the point that this decision, by allowing existing operators to challenge permits granted to competitors, effectively enables them to act as "private attorney generals" ensuring the legality and proper administration of the permit system, which ultimately benefits public health and the environment. This highlights the "legality assurance function" of administrative litigation.

Conclusion

The 2014 Supreme Court decision concerning general waste management permits in Obama City represents an important development in the law of plaintiff standing for competitors in Japan. It demonstrates that even in the absence of explicit statutory provisions protecting existing businesses from competition (like direct distance limitations), a "legally protected interest" can be found if the overall regulatory scheme, its purposes, and the nature of the regulated business indicate an implicit legislative intent to safeguard the operational stability of existing, compliant permit holders as a means of ensuring the effective delivery of essential public services.

The Court's focus on the public service nature of waste management and the role of the municipal General Waste Management Plan in adjusting supply and demand was key to its finding. This decision suggests a more nuanced and purposive approach to interpreting regulatory statutes when determining whether existing businesses have the right to challenge permits granted to their competitors, particularly in sectors deeply imbued with public interest.