Balancing Budgets and Basic Needs: Japan's Supreme Court on Revising Public Assistance Standards

A Third Petty Bench Ruling from February 28, 2012

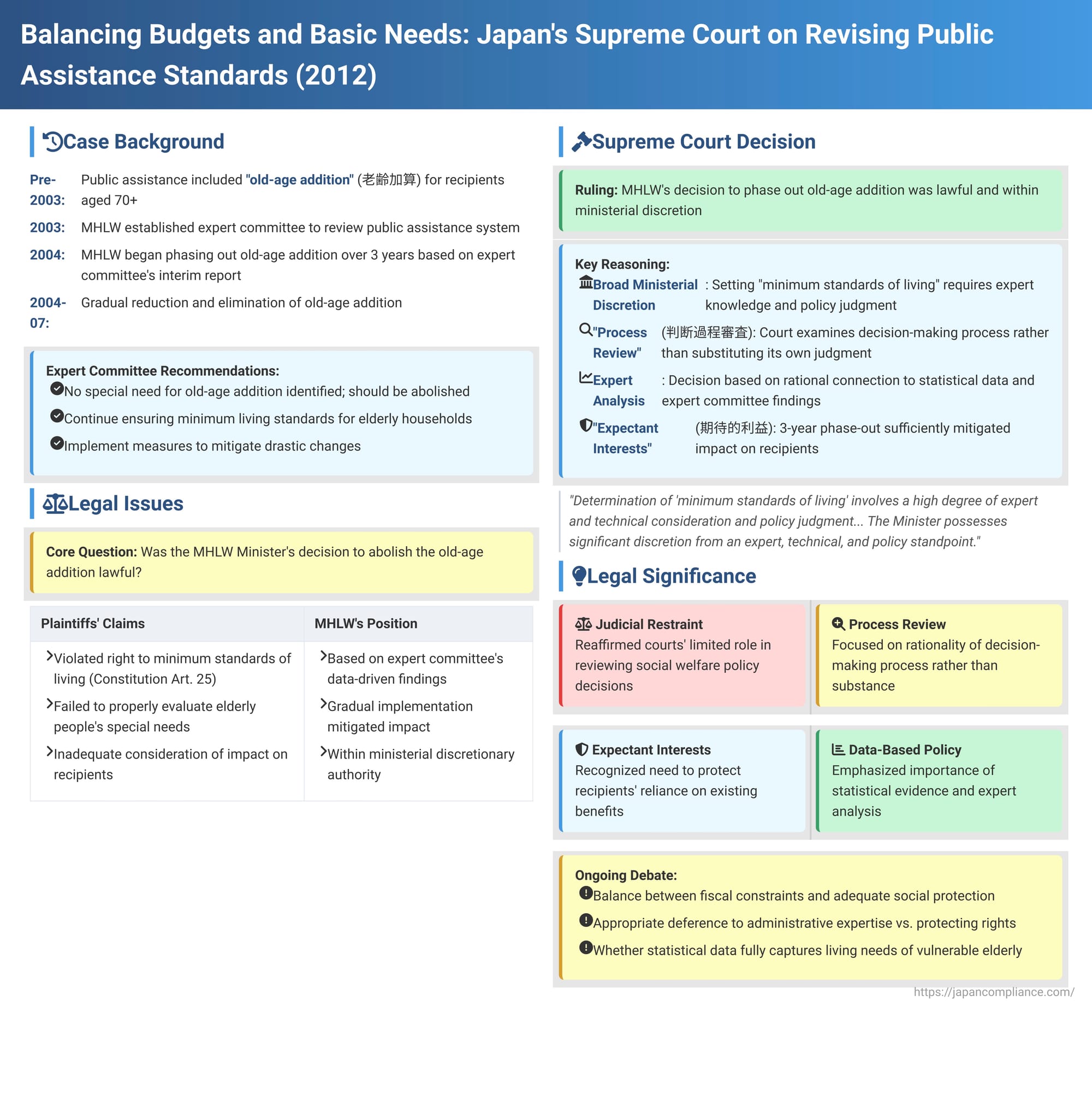

Public assistance programs sit at the complex intersection of social welfare policy, fiscal responsibility, and fundamental human rights. Defining what constitutes "minimum standards of living" and how these standards should be implemented and, at times, revised, often involves intricate expert analysis and significant policy choices by government authorities. A pair of Japanese Supreme Court decisions in 2012, with the lead judgment issued by the Third Petty Bench on February 28, 2012 (Heisei 22 (Gyo Tsu) No. 392, (Gyo Hi) No. 416), delved into the legality of revisions made by the Minister of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW) to the standards for public assistance, specifically the phasing out of an "old-age addition" benefit. This blog post will primarily focus on the reasoning of the February 28, 2012 judgment (referred to as Judgment ①).

The Context: Revising the "Old-Age Addition"

Under Japan's Public Assistance Act (生活保護法 - Seikatsu Hogo Hō), the MHLW Minister is responsible for establishing the specific criteria, or "public assistance standards" (保護基準 - hogo kijun), that determine the level of assistance provided. These standards are typically set by an MHLW Notification, a form of administrative regulation. For many years, these standards included an "old-age addition" (老齢加算 - rōrei kasan), a supplementary payment generally provided as part of livelihood assistance to individuals aged 70 and older.

In 2003, amid broader discussions about social security reform, the MHLW established an expert committee within its Social Security Council to review the public assistance system, including the old-age addition. This expert committee subsequently published an interim report (中間とりまとめ - chūkan torimatome) with several key findings and recommendations:

- (ア) Based on a comparison of consumption expenditures in single, unemployed elderly households, the committee found that "no special need equivalent to the current old-age addition is recognized for those aged 70 or older; therefore, the old-age addition itself should be reviewed with a view to abolition."

- (イ) However, the report also stated that "consideration should continue to be given to maintaining the minimum living standard of elderly households within the protection standard system, taking into account the expenses necessary for their social life."

- (ウ) Furthermore, it recommended that "measures should be taken to mitigate drastic changes so that the living standards of protected households do not decline suddenly."

Following the release of this interim report, from fiscal year 2004 onwards, the MHLW Minister initiated a series of revisions to the public assistance standards. These revisions (collectively referred to as 本件改定 - honken kaitei, "the present revisions") aimed to incrementally reduce and eventually phase out the old-age addition.

The Legal Challenge: Welfare Recipients Sue

The plaintiffs in Judgment ① were recipients of public assistance residing in Tokyo. As a result of the MHLW's revisions to the standards, their local welfare offices issued decisions that reduced their livelihood assistance payments due to the phasing out of the old-age addition. The plaintiffs challenged these decisions, arguing that the MHLW's underlying revision of the public assistance standards was unlawful and unconstitutional, violating Article 25 of the Constitution (which guarantees the right to minimum standards of wholesome and cultured living) and various provisions of the Public Assistance Act. With some exceptions in related cases (notably the appellate court decision in a similar case referred to as Judgment ②), lower courts had largely dismissed these claims.

The Supreme Court's Decision (Judgment ① - February 28, 2012)

The Supreme Court's Third Petty Bench dismissed the plaintiffs' appeal in Judgment ①, ultimately upholding the legality of the MHLW Minister's decision to revise the standards and phase out the old-age addition in this specific instance.

Minister's Broad Discretion in Setting Standards:

The Court began by reaffirming the extensive discretion vested in the MHLW Minister when it comes to defining "minimum standards of living" and setting the specific levels of public assistance.

- It reiterated that the concept of "minimum standards of living," as mentioned in Article 25 of the Constitution and Articles 3 and 8(2) of the Public Assistance Act, is "abstract and relative." Its concrete content must be determined in correlation with the economic and social conditions of the time, the general standard of national life, and other relevant factors.

- Translating this abstract concept into concrete public assistance standards necessitates "a high degree of expert and technical consideration and policy judgment based thereon." This point referenced a 1982 Supreme Court Grand Bench decision (the Horiki case), a landmark ruling on social welfare rights.

- Therefore, when deciding to revise the old-age addition component of the standards, the MHLW Minister possesses significant discretion from an "expert, technical, and policy standpoint." This discretion extends to judging (a) whether a "special need" attributable to old age truly exists to justify such an addition, and (b) whether the revised livelihood assistance standards for the elderly remain sufficient to "maintain a healthy and cultured living standard."

Consideration of "Expectant Interests" and Mitigating Measures:

The Court also acknowledged that abolishing the old-age addition could negatively affect recipients who had structured their lives and finances based on the expectation of receiving this benefit.

- The abolition could lead to a "loss of their expectant interest (期待的利益 - kitaiteki rieki) that had been concretized by the protection standards."

- In light of this, the MHLW Minister also has discretion—from the same expert, technical, and policy standpoint—in determining the specific methods for phasing out the addition. This includes deciding on the necessity and nature of "measures to mitigate drastic changes" (激変緩和措置 - gekihen kanwa sochi) to give "due consideration as much as possible" to these expectant interests of the recipients.

Standard of Judicial Review: "Process Review":

The Supreme Court outlined the standard by which it would review the Minister's exercise of discretion in revising the standards. The revision (specifically, the abolition of the old-age addition) would be deemed illegal if:

- The Minister's judgment—that there was no longer a special need for the old-age addition for those aged 70 and above, and that the revised standards for the elderly were still adequate—was found to suffer from "an error or omission in the process and procedures of judgment regarding the concretization of minimum standards of living," or if it otherwise constituted an abuse or deviation of discretionary power. This approach is often termed "process review" (判断過程審査 - handan katei shinsa).

- The Minister's decision regarding whether to adopt mitigating measures (and the specific measures chosen, if any) was found to be an abuse or deviation of discretion when viewed from the perspective of the "expectant interests of the protected persons and the impact on their lives."

Application to the Facts of This Case:

Applying this framework, the Supreme Court found the MHLW's actions lawful:

- Validity of the Minister's Judgment on "Special Need": The Court examined the expert committee's interim report, which had recommended abolishing the old-age addition. This report was based on various statistical comparisons: consumption expenditures of elderly households (comparing those 70+ with the 60-69 age group, and comparing welfare recipients with low-income non-recipients), trends in public assistance standards versus the Consumer Price Index (CPI) and wage growth, and changes in Engel's coefficient (proportion of income spent on food) among low-income households. The Supreme Court found that this report exhibited "no lack of rational connection with objective numerical data such as statistics, or consistency with expert knowledge." Since the MHLW Minister's decision to abolish the old-age addition aligned with the expert committee's opinion (specifically, point (ア) regarding the absence of a special need), and there were no discernible errors or omissions in the judgment process or procedures, this aspect of the Minister's decision was upheld.

- Adequacy of Mitigating Measures: The MHLW implemented the abolition of the old-age addition gradually over a three-year period, which was in line with the expert committee's recommendation (point (ウ)). The Court noted data indicating that the net savings of households receiving the old-age addition were already close to the amount of the addition itself, and their savings were significantly higher than those of households not receiving the addition. Based on this, the Court concluded that the three-year phase-out "can be evaluated as having considerably alleviated the impact on protected households." Additionally, the MHLW conducted periodic reviews of the overall livelihood assistance standards, taking into account the expert committee's call to ensure the maintenance of minimum living standards (point (イ)), which also served to prevent sudden, drastic declines. Therefore, the reduction in assistance due to the abolition of the old-age addition "cannot be evaluated as having had an undeniable impact on their lives through the loss of expectant interest."

The Supreme Court thus concluded that the MHLW Minister's revision of the public assistance standards did not constitute an abuse or deviation of discretion and was not illegal.

Understanding the Legal Concepts

This case touches on several important legal concepts in Japanese administrative and constitutional law:

- "Minimum standards of wholesome and cultured living": This phrase from Article 25 of the Constitution is the bedrock of Japan's social welfare system. However, its concrete meaning is not fixed and is subject to interpretation by the MHLW Minister, guided by socio-economic conditions and expert advice.

- Ministerial Discretion: The MHLW Minister is granted significant discretion in setting public assistance standards due to the complex, technical, and policy-laden nature of these decisions. This discretion, while broad, is not unlimited.

- "Expectant Interests" / Protection of Reliance (信頼保護 - shinrai hogo): Administrative law recognizes that individuals may develop legitimate expectations based on existing government policies or benefits. When changing these policies to the detriment of individuals, the government often needs to consider these reliance or expectant interests, for example, by providing transitional measures or phasing in changes. The commentary accompanying the case material suggests a link between the Court's discussion of "expectant interests" and the broader legal principle of protecting reliance.

- "Process Review" (判断過程審査 - handan katei shinsa): This is a method of judicial review where courts scrutinize the decision-making process of an administrative body rather than directly substituting their own judgment on the substantive outcome, especially in areas where the administration has broad discretion and expertise. The review focuses on whether the agency considered relevant factors, avoided irrelevant ones, based its decision on accurate facts and rational analysis, and followed proper procedures. This case is a notable application of process review to administrative rulemaking (specifically, the setting of public assistance standards by MHLW notification).

The Role of Expert Committees and Data

The Supreme Court's judgment placed considerable weight on the findings and recommendations of the MHLW's expert committee.

- The Court deferred to the committee's conclusions where they were supported by a "rational connection with objective numerical data such as statistics" and demonstrated "consistency with expert knowledge."

- This underscores the importance for administrative agencies, when making discretionary decisions with significant public impact, to base their judgments on solid evidence, transparent analysis, and expert input. The judiciary, in turn, will examine this evidentiary basis and analytical process as part of its review.

A Note on Judgment ②

A similar case, decided by the Supreme Court's Second Petty Bench on April 2, 2012 (referred to as Judgment ②), largely adopted the same legal framework as Judgment ①. However, in Judgment ②, the Tokyo High Court had actually found the MHLW's revision illegal, reasoning that the Minister had made the decision to abolish the old-age addition too quickly after the expert committee's interim report was published and had not adequately considered the report's recommendations regarding the maintenance of overall living standards (point (イ)) and the implementation of mitigating measures (point (ウ)). The Supreme Court, in Judgment ②, disagreed with this part of the High Court's assessment. It stated that the expert committee's opinion was not legally binding on the Minister but rather one important factor to be considered. It found that the MHLW's revision process did not, in fact, ignore the overall intent of the expert committee's report and remanded the case for further consideration by the High Court under the framework it had laid out.

Critical Perspectives and Ongoing Debate

While the Supreme Court upheld the MHLW's decision in Judgment ①, the case and its reasoning have been subject to legal commentary and analysis.

- Extent of Deference: The broad discretion afforded to the MHLW Minister in defining minimum living standards is a recurring theme, tracing back to earlier landmark cases like Asahi (1967) and Horiki (1982). The "process review" approach allows courts to intervene if the decision-making process is flawed, but the threshold for finding such flaws can be high.

- Adequacy of Consideration: Critics, including some lower court judges in related cases, questioned whether the MHLW truly gave sufficient weight to all aspects of the expert committee's report, particularly the nuanced calls to ensure overall living standards for the elderly were maintained and that mitigating measures were robustly implemented, rather than focusing primarily on the recommendation to abolish the specific "old-age addition".

- Data and Living Realities: There have been concerns raised by some legal scholars and advocates about whether the statistical data and analyses fully captured the actual, complex living conditions and needs of vulnerable elderly individuals, especially those living alone. The transparency and methodology of the underlying statistical surveys have also been points of discussion.

- Challenge for Courts: These cases highlight the inherent difficulty for courts when reviewing complex socio-economic policy decisions that are embedded in administrative regulations and involve balancing competing interests, expert knowledge, and fiscal constraints.

Conclusion

The 2012 Supreme Court judgments concerning the revision of the old-age addition to public assistance are significant for their detailed articulation of the scope of ministerial discretion in the crucial area of social welfare standard-setting. They confirm that while the MHLW Minister possesses broad authority, this discretion is not unfettered and is subject to judicial review focused on the rationality and procedural integrity of the decision-making process. The emphasis on considering the "expectant interests" of beneficiaries and the need for objective data and expert analysis in justifying changes to welfare standards are key takeaways. These rulings continue to inform the legal understanding of how Japan balances the state's responsibility to provide for minimum standards of living with the practicalities of policy implementation and fiscal management.