Balancing Benefits and Damages: Japan's Supreme Court on Offsetting Future Workers' Comp Payments (October 25, 1977)

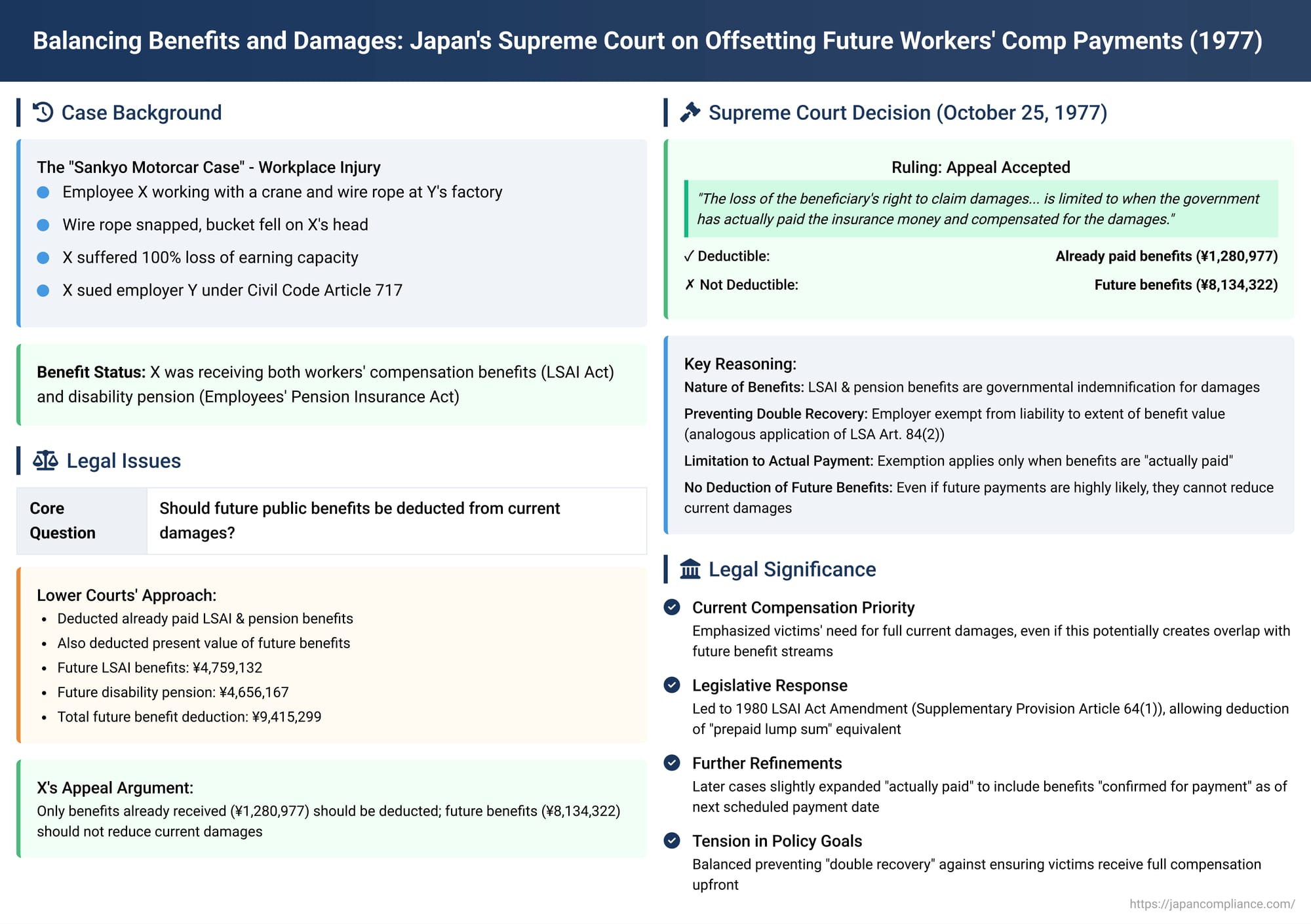

On October 25, 1977, the Third Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan delivered a crucial judgment in a damages claim case, known by commentators as the "Sankyo Motorcar Case" (三共自動車事件). This ruling addressed a pivotal question in Japanese labor and tort law: when an employee suffers a work-related injury due to employer fault and is eligible for both workers' compensation insurance benefits and social security payments (like disability pensions), how should these public benefits be adjusted against the employer's civil liability for damages? Specifically, the Court focused on whether anticipated future payments from these public schemes should be deducted from a current damages award.

The Accident and the Initial Claim for Damages

The plaintiff, X, was an employee of Defendant Y, an automotive company. While working at Y's main factory, X was engaged in an operation using a factory-provided crane and wire rope to lift the bucket of a shovel car. During this task, the wire rope unexpectedly snapped. The heavy bucket fell directly onto X's head, inflicting severe injuries that resulted in a permanent 100% loss of X's earning capacity.

Plaintiff X subsequently filed a lawsuit against Defendant Y, seeking compensation for damages. The claim included lost future earnings, solatium (compensation for pain and suffering), and other related costs. The legal basis for the claim was Article 717 of the Civil Code, which pertains to liability for defects in the installation or maintenance of structures on land (in this instance, the allegedly defective wire rope owned by Company Y).

Lower Courts: Deducting Both Past and Future Benefits

The case progressed through the lower courts with differing outcomes regarding the extent of deductions for public benefits:

- First Instance (Matsuyama District Court, Uwajima Branch): The trial court found Company Y liable for damages under Civil Code Article 717. In calculating the amount of damages, particularly for lost earnings, the court made two key deductions related to public benefits received or anticipated by X:

- It deducted the sum of work absence compensation benefits (休業補償給付 - kyūgyō hoshō kyūfu) and long-term disability compensation benefits (長期傷病補償給付 - chōki shōbyō hoshō kyūfu) that had already been paid to X under Japan's Workers' Accident Compensation Insurance Act (LSAI Act). The court cited Article 84 of the Labor Standards Act (LSA) as a basis for this adjustment.

- Significantly, it also deducted the present cash value of future long-term disability compensation benefits (or alternatively, disability compensation benefits - 障害補償給付, shōgai hoshō kyūfu) that X was projected to receive from the LSAI Act. This future stream of payments was converted into a lump sum and subtracted from the damages award.

- Appeal (Takamatsu High Court): The High Court upheld the deductions approved by the first instance court. Furthermore, it expanded the scope of deductions to include disability pension payments X was receiving under the Employees' Pension Insurance Act (厚生年金保険法 - Kōsei Nenkin Hoken Hō). Similar to the LSAI benefits, the High Court allowed the deduction of both the amounts of disability pension already received by X and the present cash value of anticipated future disability pension payments.

Dissatisfied with the High Court's decision to allow the deduction of future, unreceived benefit payments from his damages award, Plaintiff X appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Ruling on Future Benefit Offsets

The Supreme Court upheld X's appeal, thereby modifying the judgments of the lower courts. The core of its decision was a rejection of the practice of deducting the present value of anticipated future public benefit payments from a current civil damages award.

The Court's reasoning was articulated as follows:

- Nature of Public Insurance Benefits: The Supreme Court began by affirming that "Insurance benefits under the Workers' Accident Compensation Insurance Act are, in substance, the government providing, in the form of insurance benefits, the employer's obligations for accident compensation under the Labor Standards Act. Similar to insurance benefits under the Employees' Pension Insurance Act, they also have the nature of indemnifying the beneficiary for damages".

- Basis for Offsetting Benefits Against Damages: "Therefore, when an accident is caused by the employer's act, if the government has provided insurance benefits to the beneficiary under the LSAI Act, by analogous application of Article 84, Paragraph 2 of the Labor Standards Act, and if the government has provided insurance benefits under the Employees' Pension Insurance Act, in light of the principle of equity, it is reasonable to interpret that the employer is exempted from liability for damages under the Civil Code for the same cause, to the extent of the value of those benefits". This established the general principle of offsetting to prevent double recovery.

- Crucial Limitation: Only Actual Payments Deductible: The Supreme Court then introduced a critical limitation: "And, the loss of the beneficiary's right to claim damages against the employer due to such government insurance benefits being provided, given that said insurance benefits also have the nature of indemnifying damages, is limited to when the government has actually paid the insurance money and compensated for the damages".

- No Deduction for Future, Unreceived Benefits: "As long as actual payment has not yet been made, even if it is determined that benefits will continue to be paid in the future, the beneficiary, when claiming damages against the employer, is not required to deduct such future benefit amounts from the amount of the damages claim". The Court referenced a similar holding in a previous Supreme Court judgment from May 27, 1977 (Showa 52).

Application to the Facts:

The Supreme Court noted that the High Court had calculated the present value of future LSAI long-term disability compensation benefits as 4,759,132 yen and the present value of future Employees' Pension disability pension benefits as 4,656,167 yen, resulting in a total deduction of 9,415,299 yen for anticipated future payments. However, the record showed that X had, at that point, actually received a total of 1,280,977 yen in combined LSAI and pension benefits for past periods.

Therefore, the Supreme Court found that the High Court's deduction of the remaining 8,134,322 yen (which represented the present value of future, unreceived benefits) from X's lost earnings was based on an erroneous interpretation of the law. The Supreme Court proceeded to recalculate the damages owed by Defendant Y to Plaintiff X, adding back this improperly deducted amount, and made corresponding adjustments to the delay interest.

Rationale, Implications, and Subsequent Developments

This judgment by the Supreme Court has been highly influential in shaping the practice of adjusting civil damages awards in light of workers' compensation and social security benefits.

- Preventing Double Recovery vs. Ensuring Full Compensation: The core legal tension is between the principle of preventing "double recovery" (where a victim is compensated twice for the same loss, once through public benefits and again through civil damages) and ensuring that the victim receives full compensation for all legally recognized damages from the tortfeasor/breaching party (the employer, in this case).

- Interpretation of LSA Article 84(2): The commentary notes that the Supreme Court's decision can be seen as a literal interpretation of LSA Article 84, Paragraph 2. This provision states that if an employer "has provided compensation" equivalent to that required by the LSA for a work-related accident, they are exempt from civil damages liability for the same cause, up to the value of that compensation. The Court's emphasis on "actually paid" benefits aligns with the past tense "has provided".

- The "Double Dip" Problem and Competing Perspectives:

- The immediate consequence of this ruling is that, for the period following the civil judgment, if the employee continues to receive pension-style LSAI or social security benefits, they might indeed receive payments from both the employer (via the damages award which did not deduct these future sums) and the public insurance system for the same ongoing losses (e.g., lost earning capacity).

- Criticism: This outcome has been criticized, particularly from the perspective that employers contribute LSAI premiums with the expectation that these will cover their statutory compensation liabilities. Denying the deduction of future, albeit certain, LSAI pension benefits from civil damages could be seen as diminishing this "insurance benefit" for employers.

- Support: Conversely, other viewpoints emphasize the social security and living protection aspects of LSAI and pension benefits. From this perspective, even if employers face civil liability in addition to their LSAI premium obligations, it is considered an "unavoidable" consequence of their fault-based liability, and the primary goal is to ensure the victim's welfare.

- Legislative Response – LSAI Act Supplementary Provision Article 64(1):

- Following this Supreme Court judgment, the LSAI Act was amended in 1980 (Showa 55) with the introduction of Supplementary Provision (附則 - fusoku) Article 64, Paragraph 1. This provision allows an employer who is liable for civil damages to an employee for the same incident covered by an LSAI pension to withhold payment of those damages up to an amount equivalent to the present cash value of a "prepaid lump sum" (前払一時金 - maebarai ichijikin) for that pension.

- A prepaid lump sum is an optional advance payment that a recipient of certain LSAI pensions (like survivor or disability pensions) can request. It typically corresponds to a specified number of days' worth of the "basic daily benefit amount" (e.g., 1000 days for a survivor compensation pension). Because this lump sum portion represents a legally guaranteed and quantifiable future payment, it is treated as akin to an already-paid benefit for adjustment purposes.

- However, this legislative adjustment only covers the prepaid lump sum equivalent. If pension payments continue beyond this amount, the issue of potential double recovery for that subsequent period remains.

- Subsequent Supreme Court Clarifications:

- No Employer Subrogation for LSAI Benefits: In a later case (Heisei 1.4.27), the Supreme Court denied an employer, who had paid full civil damages to an injured employee, the right to then step into the employee's shoes (subrogation under Civil Code Art. 422) and claim LSAI benefits from the government. The Court reasoned that LSAI benefits and civil damages serve different institutional purposes and objectives, meaning LSAI benefits cannot be considered a "right substituting for the compensated damages". This reasoning has drawn some academic criticism for appearing inconsistent with the principle of offsetting already paid LSAI benefits against civil damages (which implies they do compensate for the same type of loss, at least in part).

- Slight Expansion of Deductible Benefits – "Confirmed for Payment": In a Grand Bench decision (Heisei 5.3.24) concerning local public servant mutual aid survivor pensions (which have similarities to LSAI pensions), the Supreme Court refined the rule. While still denying the deduction of uncertain future benefits, it held that pension installments "whose continuation is certain to a degree comparable to actual payment" could be deducted. This primarily referred to pension installments that had accrued and were due for payment by the next scheduled payment date, even if not yet physically disbursed by the time of the civil court's oral proceedings. This effectively expanded the deductible amount slightly beyond strictly "already paid" benefits. The rationale for not deducting more distant future benefits (especially for survivor pensions) often involves the inherent uncertainty of their continuation, as entitlement can cease due to events like the survivor's remarriage or death. This "confirmed for payment" principle was later explicitly applied to LSAI survivor compensation pensions by the Supreme Court (Heisei 27.3.4). That 2015 ruling also clarified that such already-paid or confirmed-for-payment benefits are considered to have compensated the relevant portion of the damage as of the time of the tort, which has implications for how delay interest is calculated (preventing deduction from later-accruing interest).

Conclusion: Prioritizing Current Compensation for Victims

The Supreme Court's 1977 judgment in the Automotive Company Y case established a clear and influential principle: when offsetting public insurance benefits against an employer's civil damages liability for a work-related accident, only those benefits that have actually been paid or are definitively confirmed for payment can be deducted from the damages award. The Court rejected the practice of discounting anticipated future streams of pension payments to their present value and subtracting this from the current award. This approach prioritizes ensuring that the injured employee receives their full, currently assessed civil damages upfront, even if this creates a possibility of subsequent overlapping payments as long-term public pensions continue. While subsequent legislation has partially addressed the "double recovery" concern by allowing employers to offset damages against a "prepaid lump sum" equivalent of future pensions, the core principle from this case—that uncertain future benefits should not diminish a present damages award—remains a cornerstone of how such adjustments are handled in Japanese law.