Balancing Act: A Japanese Supreme Court Case on Garages, Common Utilities, and Exclusive Ownership

Date of Judgment: July 17, 1981

Case: Supreme Court of Japan, 1980 (O) No. 554 – Claim for Cancellation of Ownership Preservation Registration, etc.

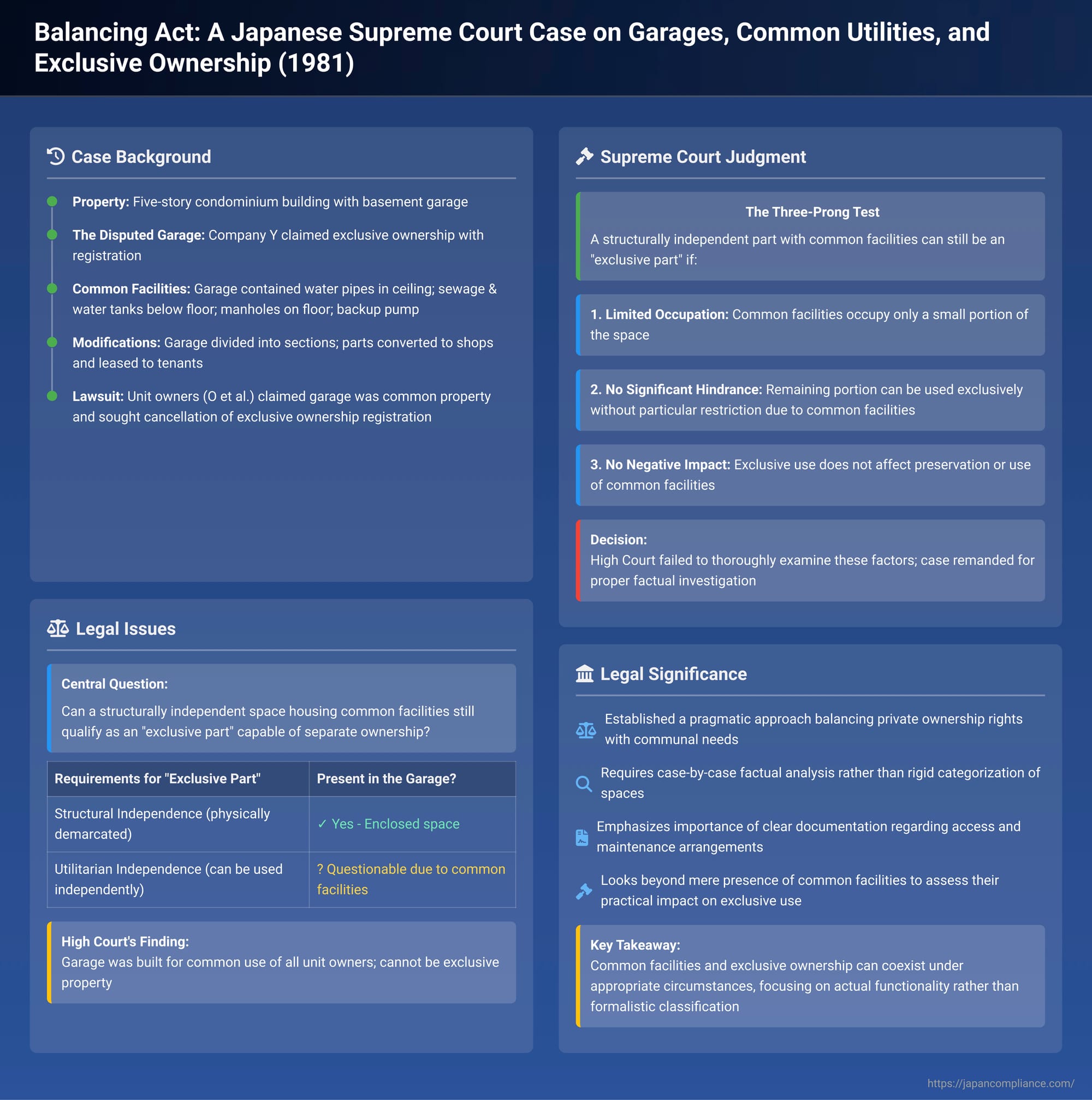

In multi-unit condominium buildings, the delineation between privately owned "exclusive parts" and communally owned "common parts" is a frequent source of legal contention. This is particularly true for spaces like garages or basements that might be structurally distinct yet house essential utilities serving all residents. A landmark decision by the Supreme Court of Japan on July 17, 1981, tackled this very issue, providing a nuanced test for determining when such a dual-purpose space can still be considered an exclusive part, capable of separate ownership. This case offers significant insights into the interpretation of Japan's Act on Unit Ownership of Buildings, especially concerning the crucial concept of "utilitarian independence" in the presence of shared facilities.

The Property in Question: A Condominium Garage Housing Essential Services

The dispute arose in connection with a five-story reinforced concrete building with a basement and a rooftop penthouse, constructed in 1965 by a company, let's call it Company Y. The building was a mixed-use condominium, featuring commercial units and residential apartments. The basement originally contained four shop units, an office, a hall in front of the stairs, and the central point of the dispute: a vehicle garage (referred to herein as the "subject garage"). The upper floors (1 through 5) housed residential units, and there was a penthouse on the 6th floor (rooftop), making a total of 26 separately owned units in the condominium. Company Y sold these individual condominium units to various parties, including O and eight others, the plaintiffs in this case.

The subject garage was not just an empty space for parking. Its ceiling featured various pipes, including water supply and miscellaneous wastewater drainage lines for the building. More significantly, beneath its floor lay a sewage purification tank and a water receiving tank, both of which were essential common facilities shared by all unit owners in the condominium. Access for the inspection, cleaning, and maintenance of these subterranean tanks was provided by several manholes set into the floor of the garage. A hand-operated backup pump for the drainage system was also located within the garage. Consequently, any work related to the upkeep of these vital shared systems necessitated physical entry into and work within the subject garage.

Despite the presence of these common utilities, Company Y had obtained an ownership preservation registration for the subject garage, treating it as its own exclusive property. Subsequently, Company Y modified parts of the garage. It divided a portion into three distinct sections—A, B, and C. Sections A and B were leased to tenants who converted them into shops. Section C was also modified into a shop with a wooden floor and leased to Mr. K (who, along with Company Y, became an appellant in the Supreme Court). Company Y itself continued to use the remaining, unaltered portion of the subject garage for parking. Thus, Company Y and its tenants (including K) occupied the entire garage area.

O and the other unit owners initiated legal proceedings. Their primary assertion was that the subject garage, due to its integral common facilities, should be classified as a common part of the condominium, owned collectively by all unit owners. Based on their claimed co-ownership rights, they demanded that Company Y cancel its ownership registration for the garage. They also sought possession of the entire garage space and monetary damages equivalent to lost rental income from Company Y. Similar claims for possession and damages were made against the tenants of sections A, B, and C, including Mr. K.

The Lower Court's Finding: A Common Area by Design

The High Court, acting as the lower appellate court in this instance, ruled in favor of O and the other unit owners. It reasoned that the subject garage was originally established to meet the parking needs of the condominium residents. Furthermore, given its structure—which effectively combined parking with housing essential building mechanicals—the High Court concluded that the garage was constructed for the common use of all unit owners. On this basis, the High Court held that the subject garage could not be the object of separate, exclusive ownership and should be considered a common part of the building under the Act on Unit Ownership of Buildings. This decision effectively denied Company Y's claim to exclusive ownership. Aggrieved by this outcome, Company Y and Mr. K (the lessee of section C) appealed to the Supreme Court of Japan.

The Supreme Court's Intervention: Crafting a Test for Dual-Function Spaces

The Supreme Court, in its judgment of July 17, 1981, took a different approach. It quashed the High Court's decision concerning Company Y and Mr. K and remanded the case back to the High Court for further proceedings. The Supreme Court found that the High Court had not sufficiently examined the facts in light of the correct legal principles applicable to such situations.

The Court articulated a crucial three-prong test, referencing a very recent prior judgment (Supreme Court, June 18, 1981, First Petty Bench, 1978 (O) No. 1373), for determining whether a building part that is structurally independent but also houses common facilities can still qualify as an exclusive part:

"Even if a part of a building, which is structurally demarcated from other parts and has the external characteristics to be used as an independent building, has facilities for the common use of other unit owners installed in a portion thereof and thus partially bears the meaning or function as a location for such common facilities, it can still be the object of unit ownership as an exclusive part of the building under the Act on Unit Ownership of Buildings, if the following conditions are met:

- The said common facilities occupy only a small portion of the said building part.

- The remaining portion of the building part can be put to exclusive use in a manner substantially no different from that of an independent building, and such exclusive use is not subject to any particular restriction or hindrance due to the use and management of the said common facilities by other unit owners.

- Conversely, such exclusive use does not affect the preservation of the common facilities or their use by other unit owners."

Applying this test to the facts of the case, the Supreme Court found the High Court's findings lacking. The High Court had established that the subject garage was structurally demarcated and had the external form for independent use. It also detailed the common facilities: pipes on the ceiling, a sewage purification tank and water receiving tank under the floor, manholes on the floor surface, and a manual pump. Technicians were expected to enter the garage periodically (monthly for inspections and disinfectant addition, annually or biannually for cleaning) and as needed for repairs to these systems, which might sometimes be extensive.

However, the Supreme Court pointed out that these facts alone merely indicated the presence of common facilities and the need for access. The High Court had not made clear findings on the critical question of whether the use and management of these common facilities would cause particular (or significant) restriction or hindrance to the exclusive use of the garage. Furthermore, the Supreme Court stated that there was insufficient basis to conclude that a garage within a condominium is automatically a common part simply because it is a garage.

Therefore, the Supreme Court concluded that, based solely on the facts determined by the High Court, it was not possible to definitively deny that the subject garage could be an exclusive part under the Act on Unit Ownership of Buildings. The High Court's judgment, which had declared the garage a common part without fully considering these points, was deemed to have erred in the interpretation and application of the Act. This error was significant enough to affect the outcome, necessitating a reversal and remand for a more thorough examination of the facts against the three-prong test.

Legal Principles: Revisiting Structural and Utilitarian Independence

This case, and the test it applied, delves into the core requirements for a space to be considered an "exclusive part" (sen'yū bubun) under Japanese condominium law—namely, structural independence and utilitarian independence.

- Structural Independence (Kōzōjō no Dokuritsusei): This refers to the physical delineation of a unit from other parts of the building by walls, floors, ceilings, etc., making it clearly identifiable and capable of distinct physical control. The subject garage, being enclosed by walls and having defined access points, generally met this criterion.

- Utilitarian Independence (Riyōjō no Dokuritsusei): This means the unit must be capable of being used independently for its intended purpose (e.g., as a residence, shop, office, or warehouse) without relying on or being inherently indivisible from other parts of the building for its basic function.

The challenge in this case, and many like it, arises when a structurally independent space also incorporates elements essential for the common use of other unit owners. Does the presence of such common facilities automatically negate utilitarian independence? The Supreme Court's three-prong test provides a more nuanced answer: not necessarily. It allows for a finding of utilitarian independence—and thus exclusive ownership—if the impact of the common facilities is limited and manageable.

The Three-Prong Test: A Closer Look

The Supreme Court’s test provides a structured way to assess situations where private space and common utilities intersect:

- "Small Portion" Occupied by Common Facilities: This first prong suggests a quantitative or spatial assessment. If the common utilities physically dominate the space or render a substantial part of it unusable for its primary exclusive purpose, then it's less likely to qualify as an exclusive part. The pipes on the ceiling and manholes on the floor of the garage might be considered, but the large tanks underneath the floor, while significant, didn't occupy the usable volume of the garage itself, only the sub-floor space. The key is how much of the usable area of the purported exclusive part is taken up or directly affected by the physical presence of these facilities.

- "No Significant Restriction or Hindrance" to Exclusive Use: This is often the most critical and fact-intensive prong. It’s not enough that common facilities exist or that access is sometimes required. The question is whether this access, or the general presence and operation of the facilities, substantially impairs the owner's ability to use the space exclusively for its intended purpose. For example, if maintenance required the garage to be cleared of vehicles for extended periods very frequently, that might constitute a significant hindrance. Occasional, scheduled access for routine checks might not. The Supreme Court emphasized that the High Court had not made clear findings on this specific point regarding the garage.

- "No Adverse Impact" on Common Facilities from Exclusive Use: This prong looks at the compatibility from the other direction. The exclusive use of the space must not damage, obstruct, or otherwise interfere with the proper functioning, maintenance, or accessibility of the common facilities for other unit owners. For instance, if using the garage for a particular type of business involved vibrations or substances that could damage the underfloor tanks or pipes, this condition might not be met.

The introduction and application of this test marked a shift towards a more practical, fact-based analysis, moving away from potentially rigid interpretations that any space housing common utilities must automatically be a common area.

Implications and Subsequent Developments

This 1981 Supreme Court decision, by applying the test articulated in the June 18, 1981 judgment, has had lasting implications:

- Guidance for Developers and Owners: It provides a framework for how spaces with mixed private and common-utility functions might be designed and legally structured. Developers wishing to retain exclusive ownership over such areas must ensure the design and operational plans can satisfy the three-prong test.

- Importance of Clear Documentation: For spaces deemed exclusive parts despite housing common utilities, it highlights the need for clear agreements or bylaws governing access for maintenance, responsibilities, and how potential interferences will be managed.

- Burden of Proof: Parties in a dispute need to provide detailed factual evidence. Those arguing a space is a common part despite its structural independence would need to show, for example, that the common facilities occupy a substantial portion, or that their maintenance significantly hinders exclusive use, or that exclusive use endangers the facilities. Conversely, those arguing for exclusive part status need to demonstrate the opposite.

- Focus on Substantive Impact: The courts, following this line of reasoning, would look beyond the mere presence of common elements to the actual, practical impact on the use and enjoyment of the space by the purported exclusive owner and on the common facilities by all unit owners.

Commentary on this line of decisions indicates that subsequent Supreme Court rulings, such as one in 1986 (Showa 61, April 25, concerning a warehouse after remand of a case also initially decided on June 18, 1981), further solidified the importance of prongs 2 and 3 of the test. These cases consistently emphasize that a thorough investigation of the specific use of the purported exclusive part, the nature of the common facilities, and the practicalities of their coexistence is indispensable. Formalistic arguments ("it's a garage, so it's common") are insufficient. The actual details of potential interference with exclusive use, and any impact on the preservation and use of common facilities, must be meticulously examined.

Conclusion: Striving for a Practical Balance

The Supreme Court's July 17, 1981, decision regarding the condominium garage provides a vital precedent in Japanese property law. It demonstrates a judicial willingness to adopt a pragmatic and balanced approach when assessing the status of building parts that serve both private and common functions. By establishing and applying the three-prong test, the Court acknowledged that exclusive ownership can be compatible with the presence of common utilities, provided that the common facilities are limited in their footprint and their operation and maintenance do not unduly interfere with the exclusive use of the space, nor does the exclusive use compromise the common facilities. This ruling, and the line of cases it belongs to, underscores a functional approach to property rights in shared buildings, aiming to reconcile the rights of individual owners with the collective needs of the condominium community. It requires a careful, case-by-case analysis of the facts rather than a rigid application of definitions, ensuring that the legal status of a space aligns with its practical reality and intended use within the building as a whole.