"Bad Faith Acquirer" in Property Chains: Does the Taint Pass to Subsequent Buyers?

Case Reference: Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench, Judgment of October 29, 1996 (Heisei 8) (Case No. 956 (O) of 1993 (Heisei 5))

Subject Matter: Claim for Confirmation of Public Road, etc. (公道確認等請求事件 - Kōdō Kakunin tō Seikyū Jiken)

Introduction

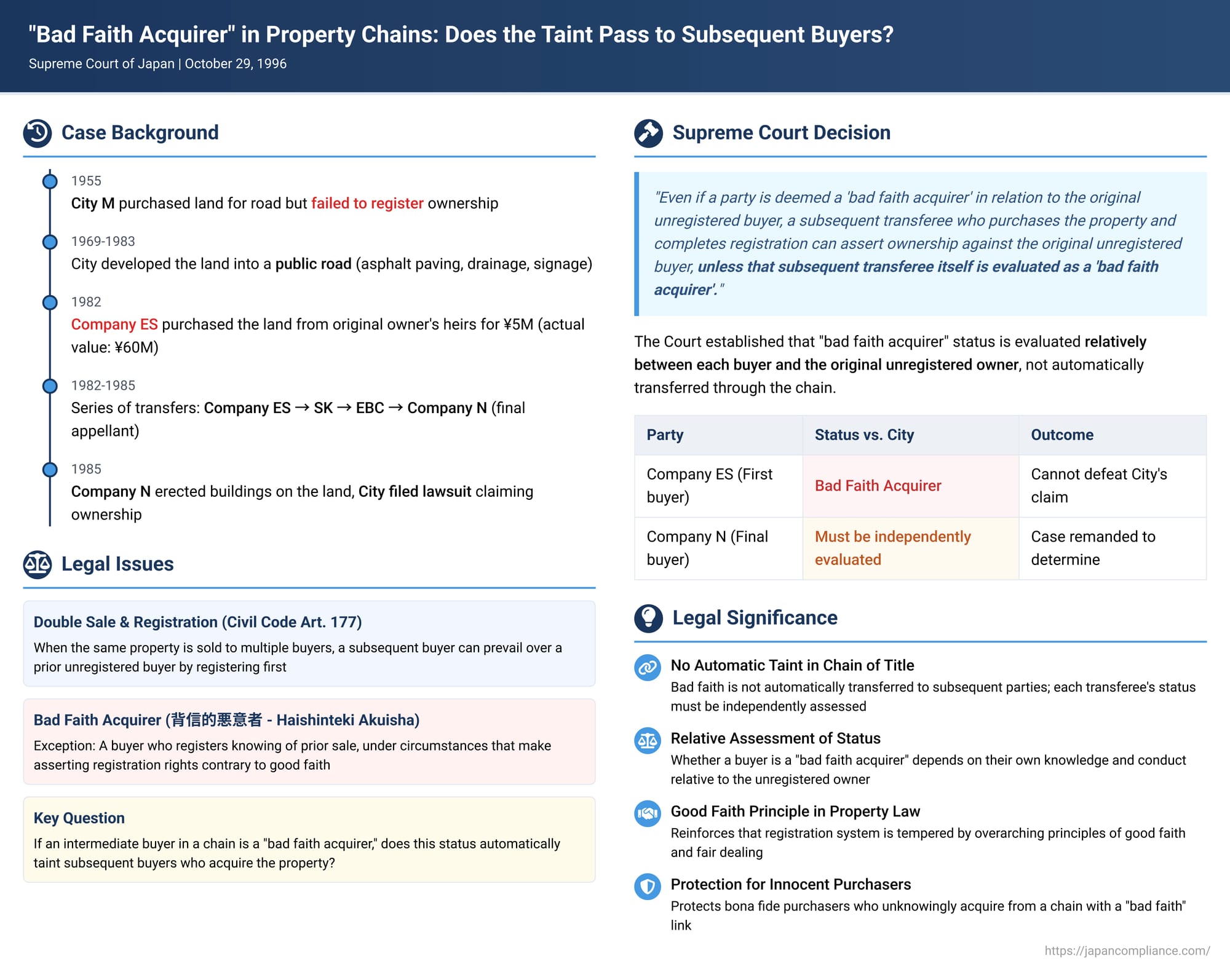

This article delves into a 1996 Japanese Supreme Court judgment that addresses a nuanced scenario in real property law involving a "double sale" and the concept of a "bad faith actor with notice amounting to a breach of trust" (背信的悪意者 - haishinteki akuisha). Specifically, the case examines whether a subsequent purchaser of land can be defeated by a prior unregistered owner if an intermediate purchaser in the chain of title was a "haishinteki akuisha." The Court clarified that the status of being a "haishinteki akuisha" is assessed relatively between the first unregistered buyer and each subsequent registered buyer, and the bad faith of an intermediary does not automatically taint an otherwise non-bad-faith final purchaser.

The dispute involved the City of M (appellee/plaintiff), which had purchased land for a road but failed to register its ownership, and Company N (appellant/defendant), which subsequently acquired and registered the same land through a chain of transactions originating from the original owner's heirs.

Factual Background

In March 1955, the City of M purchased a parcel of land (the "Land") from its then-owner, Original Owner H, as part of a project to develop a road for freight access near the former Matsuyama National Railway Station. The City paid the full purchase price. However, due to an error in the land subdivision and registration process, the specific parcel intended for the City (to be designated "Parcel 6") was incorrectly recorded under a different designation ("Parcel 7"), and crucially, ownership registration in the City's name was never completed for the intended Land. The Land remained registered under Original Owner H's name.

Despite the lack of registration, the City proceeded to develop the Land. In 1955, it carried out landfill work. Between June and July 1969, it installed drainage ditches on the north and south sides, placed two manholes with the city emblem in the central part, and paved the entire area with asphalt, developing it into a road substantially similar to its current form. By November 1979, the City had also installed a metal "City Road" marker on the Land. The Land had been used by the general public as a city road since at least July 1969 and was recognized as such by local residents. Official city road ledgers also listed it as "City Road Shintama 286-1." In January 1983, the City formally designated the area as "City Road Shintama 286-1" under the Road Act and publicly announced its commencement of use (later renamed "Shintama Route 47").

Years later, in the summer of 1982, Agent N, who was involved in managing Original Owner H's family assets, was consulted by Original Owner H's family about disposing of land that was still registered in H's name but whose location was uncertain, for which they were still paying fixed asset taxes. Agent N, with the help of W (an acquaintance and effective owner of several companies), identified the Land as one such parcel.

On October 25, 1982, W, acting as an agent for his company, Company ES, entered into a sales contract with Agent N (acting for Original Owner H) to purchase the Land for JPY 5 million. On October 27, 1982, Company ES completed the ownership transfer registration. At the time, Agent N was unsure if the Land actually existed or could be properly transferred and obtained a waiver from W stating that no refund would be sought if the land turned out to be non-existent. The estimated value of the Land in 1982, if not used as a road, was approximately JPY 60 million (and a later sale involving the appellant Company N was for JPY 150 million).

Subsequently, the Land was transferred and registered from Company ES to Company SK (another of W's companies) in February 1983, and then to Company EBC (also W's company) in July 1984. Finally, on August 14, 1985, Company N (the appellant) purchased the Land from Company EBC and completed its ownership transfer registration. On August 28, 1985, Company N asserted that the Land was not a city road and erected two prefabricated buildings and barricades on it.

The City of M then filed the main lawsuit against Company N, seeking (among other things) ownership transfer registration to the City based on "restoration of true registered title," confirmation that the Land was the site of City Road Shintama Route 47, and removal of the structures. Company N counterclaimed for damages, alleging that the City's subsequent action of obtaining a provisional disposition to remove the structures and open the land for public use was a tort.

The appellate court found that Company ES (the first corporate purchaser, represented by W) was a "haishinteki akuisha." W knew the Land had been sold to the City and was actually being used as a public road for many years, but purchased it cheaply to exploit the City's lack of registration for profit. Therefore, the City could assert its ownership against Company ES without registration. The appellate court then reasoned that since Company ES was a "haishinteki akuisha," subsequent transferees in the chain (Company SK, Company EBC, and finally Company N, all effectively linked to W or acquiring from this tainted source) also could not assert ownership against the City. It thus ordered Company N to transfer registration to the City.

The Supreme Court's Judgment

The Supreme Court partially overturned the appellate court's decision. It upheld the part of the judgment concerning the City's road management rights and the dismissal of Company N's tort claim but quashed and remanded the part concerning the ownership transfer registration to the City.

- Confirmation of Company ES as a "Haishinteki Akuisha":

The Supreme Court agreed with the appellate court's finding that Company ES was indeed a "haishinteki akuisha." Given that its agent W, after site inspection, purchased land being used as a public road (worth approx. JPY 60 million) for a mere JPY 5 million (with a no-refund clause for non-existence), knowing it was used as a city road and that the City had not registered its title, with the intent to gain an unjust profit, Company ES could not assert the City's lack of registration against the City. The City could assert its ownership against Company ES without registration. - Status of a Subsequent Transferee from a "Haishinteki Akuisha":

This was the critical point of disagreement. The Supreme Court held:

"Even if a party (丙 - C in a generic A→B→C→D example, here Company ES) is deemed a 'haishinteki akuisha' in relation to the original unregistered buyer (乙 - B, here the City), a subsequent transferee (丁 - D, here Company N) who purchases the real property from such a 'haishinteki akuisha' and completes registration can assert their acquisition of ownership against the original unregistered buyer (乙 - B, the City), unless the subsequent transferee (丁 - D, Company N) itself is evaluated as a 'haishinteki akuisha' in relation to the original unregistered buyer (乙 - B, the City). "The Court's reasoning for this was twofold:- Even if the intermediate party (Company ES) is a "haishinteki akuisha" and thus cannot assert the original buyer's (City's) lack of registration, this only means the original buyer (City) can assert its unregistered ownership against that specific "haishinteki akuisha" (Company ES). It does not invalidate the sale contract between the original seller (Original Owner H's heirs) and the "haishinteki akuisha" (Company ES). Therefore, the subsequent transferee (Company N) is not acquiring from someone with no title at all.

- The reason a "haishinteki akuisha" is excluded from the protection of Article 177 (as a "third party") is because their conduct in asserting the first buyer's lack of registration, given the circumstances of their own acquisition, is contrary to the principle of good faith. Whether a registered party is excluded from being a "third party" under this doctrine must be judged relatively between that party and the first unregistered buyer.

- Remand for Assessment of Company N's Status:

Applying this to the case, Company N acquired the Land from Company EBC (which was in the chain from Company ES, the "haishinteki akuisha"). Therefore, Company N was a transferee from a "haishinteki akuisha." The Supreme Court ruled that even if Company ES was a "haishinteki akuisha," Company N could not be denied the right to assert its ownership against the City unless Company N itself was found to be a "haishinteki akuisha" in relation to the City.

The appellate court had not made this specific determination regarding Company N's own status. Its decision that Company N could not assert ownership merely because Company ES was a "haishinteki akuisha" was an error in interpreting and applying Article 177. This error affected the judgment, requiring the part concerning the ownership transfer registration claim to be quashed and remanded for further examination of whether Company N itself acted as a "haishinteki akuisha." - City's Road Management Rights Upheld:

Regarding the City's other claims, the Supreme Court affirmed that the City, having made the area designation and public use commencement decisions under the Road Act for the Land (which had long been used by the public as a road), possessed road management rights. Even if Company N subsequently acquired ownership and the City could not assert its unregistered ownership against Company N (pending the "haishinteki akuisha" determination for Company N), Company N acquired the Land subject to the restrictions imposed by the Road Act. Therefore, the City, as the road administrator, could demand confirmation that the Land was a city road site and seek the removal of Company N's structures. Company N's tort claim against the City for removing these structures (pursuant to a provisional disposition) was also unfounded, regardless of the ultimate ownership determination, because the City was exercising its legitimate road management authority.

Analysis and Implications

This 1996 Supreme Court judgment significantly refines the "haishinteki akuisha" (bad faith actor with notice amounting to a breach of trust) doctrine, particularly concerning its application to subsequent transferees.

- "Haishinteki Akuisha" Status is Relative, Not Absolute Taint: The most crucial takeaway is that the status of being a "haishinteki akuisha" is determined relatively between the first unregistered rights holder and the specific subsequent registered party in question. The "bad faith" of an intermediate purchaser does not automatically taint all subsequent purchasers in the chain. A remote purchaser (like Company N) is not necessarily precluded from asserting their registered title just because an earlier party in their chain of title (like Company ES) was a "haishinteki akuisha" in relation to the original unregistered claimant (the City).

- Each Transferee's Conduct Matters: Each subsequent registered transferee's ability to assert their title against the original unregistered right-holder must be assessed based on their own conduct and knowledge in relation to that original right-holder. The final registered owner can prevail unless they themselves are found to be a "haishinteki akuisha."

- The Intermediate "Haishinteki Akuisha" Still Acquires Title (as against the seller): The Court clarified that even if a purchaser (like Company ES) is deemed a "haishinteki akuisha" vis-à-vis a prior unregistered party (the City), the sale contract between the original seller and that "haishinteki akuisha" is not itself void. The "haishinteki akuisha" still acquires title from the seller; they are merely prevented, due to their bad faith conduct, from asserting that title (or rather, the prior party's lack of registration) against that specific prior unregistered party. This means subsequent purchasers from the "haishinteki akuisha" are not acquiring from someone with absolutely no title.

- Reaffirmation of "Haishinteki Akuisha" Doctrine: The case reaffirms the underlying doctrine that a party who acquires registered title with knowledge of a prior unregistered right and under circumstances where asserting the lack of registration would be a breach of good faith cannot claim the protection of Article 177 of the Civil Code against that specific unregistered right-holder. The finding that Company ES was such a party, given its knowledge of the City's prior purchase and long-term public use of the land as a road, coupled with its acquisition at a grossly undervalued price for speculative purposes, was upheld by the Supreme Court.

- Public Use and Road Act: The judgment also confirms that once land is validly dedicated as a public road under the Road Act, subsequent private purchasers of the land take it subject to the public's right of passage and the road administrator's management rights, even if issues regarding the underlying ownership registration persist between the private purchaser and the public entity that originally acquired the land for the road.

This ruling adds an important layer of complexity and fairness to the application of Article 177 and the "haishinteki akuisha" doctrine. It prevents an automatic "domino effect" of bad faith down a chain of title and requires a specific assessment of each registered claimant's conduct in relation to the original unregistered party. It underscores that while the registration system is paramount, its application is tempered by the overarching principle of good faith.