Back Pay and Interim Earnings in Unfair Labor Practice Dismissals: The Daini Hato Taxi Case (Supreme Court, Grand Bench, February 23, 1977)

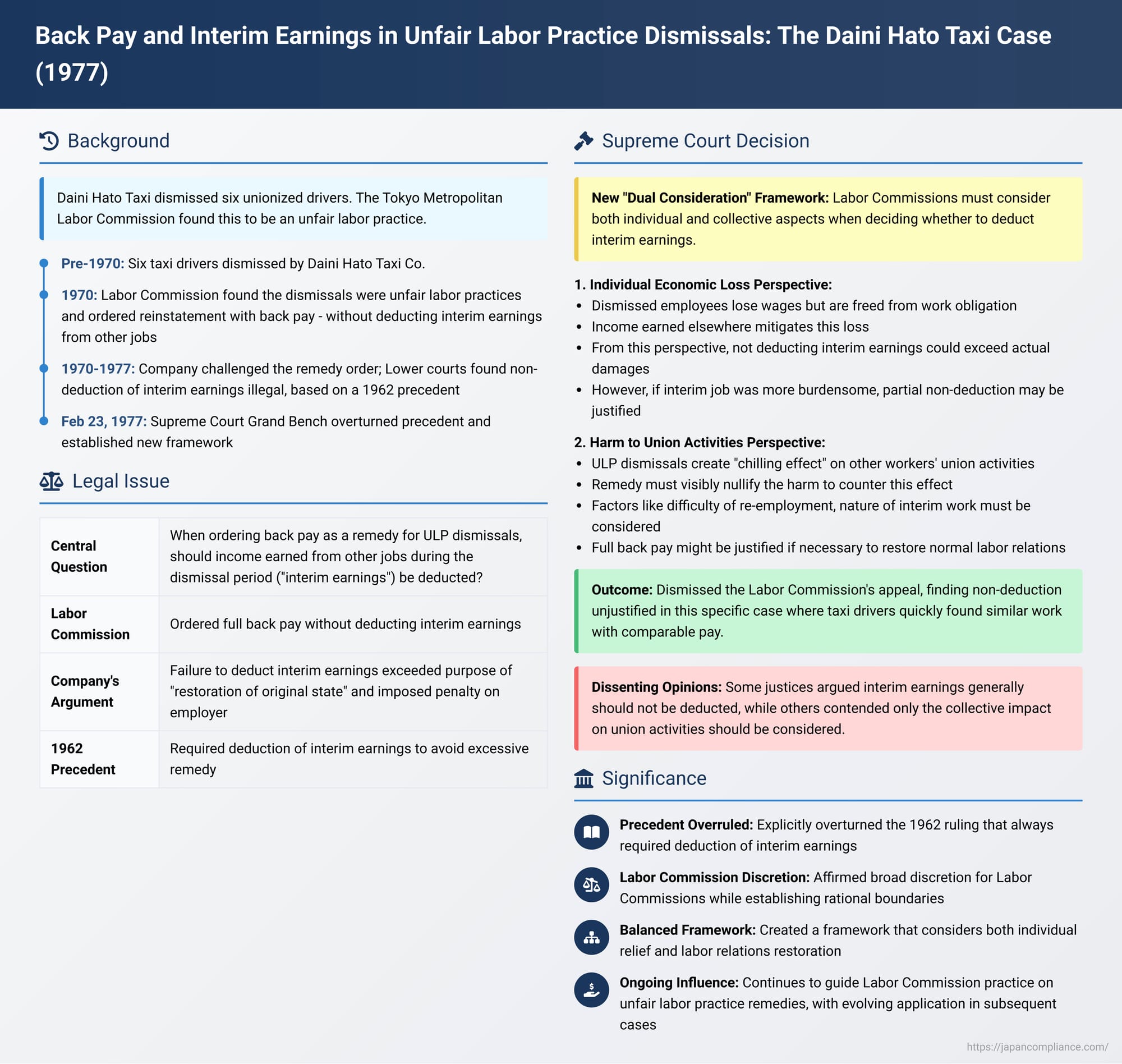

On February 23, 1977, the Grand Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan delivered a landmark judgment in the Daini Hato Taxi case. This decision significantly altered the landscape of remedies for unfair labor practice (ULP) dismissals, particularly concerning the treatment of "interim earnings"—income earned by dismissed employees from other employment during the dismissal period—when calculating back pay. The Court overruled a prior precedent and established a new "dual consideration" framework for Labor Commissions to apply, emphasizing both individual and collective aspects of ULP remedies.

Case Reference: 1970 (Gyo-Tsu) Nos. 60 & 61 (Petition for Rescission of Remedy Order)

Appellant (Original Defendant): Tokyo Metropolitan Labor Commission

Appellee (Original Plaintiff): Anzen Kogyo Co., Ltd. (successor to Daini Hato Taxi Co., Ltd. – "Company X")

Intervening Unions: Tokyo Automobile Transport Workers' Union and six others ("Union P et al.")

Judgment of the Supreme Court: The appeal by the Labor Commission is dismissed. The appellant shall bear the court costs.

Factual Background: Dismissal, ULP Finding, and the Back Pay Dispute

The case originated when Company X, a hire and taxi business, dismissed six of its unionized drivers (Employees A et al.). These employees filed an unfair labor practice claim with the Tokyo Metropolitan Labor Commission (hereinafter "Commission Y" or "the Labor Commission"). Commission Y found the dismissals to be an unfair labor practice under Article 7(1) of the Trade Union Act (TUA), which prohibits disadvantageous treatment, including dismissal, on account of union membership or proper union activities.

As a remedy, Commission Y ordered Company X to reinstate Employees A et al. to their former positions and to provide them with back pay equivalent to the wages they would have earned had they not been dismissed. Crucially, this back pay order did not require the deduction of interim earnings that Employees A et al. had obtained from other employment during the period of their dismissal.

Company X challenged this remedy order in court, specifically arguing that the portion of the order mandating back pay without deducting interim earnings was illegal. Both the Tokyo District Court and the Tokyo High Court sided with Company X, ruling that failure to deduct interim income rendered that part of the back pay order unlawful. These lower court decisions were in line with a previous Supreme Court (Third Petty Bench) judgment from 1962 (Showa 37), often referred to as the U.S. Armed Forces in Japan Procurement Office case, which had held that not deducting interim earnings exceeded the purpose of "restoration of the original state" and effectively imposed a penalty on the employer.

The Labor Commission, supported by Union P et al., appealed to the Supreme Court, setting the stage for a re-examination of the interim income deduction rule.

The Supreme Court's Grand Bench Judgment: A New Framework

The Grand Bench of the Supreme Court, while ultimately dismissing the Labor Commission's appeal in this specific instance, took the opportunity to fundamentally revise the principles governing interim income deduction in back pay orders for ULP dismissals.

I. The Nature and Purpose of the ULP Remedy System and Labor Commission Discretion

The Court first expounded on the ULP remedy system under the Trade Union Act:

- The system, established by Article 27 of the TUA, aims to protect workers' rights to organize and engage in collective action by ensuring the effectiveness of Article 7, which prohibits ULPs.

- By authorizing Labor Commissions, as expert administrative bodies, to issue remedy orders, the law intends to directly rectify the situations created by employer infringements on union activities. This serves the dual purpose of swiftly restoring and securing normal collective labor-management relations and providing flexible remedies tailored to diverse ULP scenarios, which would be difficult to specify exhaustively in advance.

- Consequently, Labor Commissions are vested with broad discretion in determining appropriate remedies. While this discretion is not unlimited and must serve the purpose of remedying ULP harm, courts reviewing these orders should respect the Commission's discretion. A remedy order should only be deemed illegal if its exercise clearly exceeds the intended purpose and objectives, or is grossly unreasonable and amounts to an abuse of power.

II. The Purpose of Remedies for ULP Dismissal: A Dual Perspective

The Court then addressed the specific context of ULP dismissals:

- A dismissal for legitimate union activity is prohibited as a ULP because it simultaneously infringes upon the individual employee's rights and interests in their employment relationship.

- Concurrently, by removing the employee from the workplace, such a dismissal suppresses or constrains general union activities among the remaining workforce.

- Therefore, the content of a remedy order (typically reinstatement and back pay) must be determined not only from the viewpoint of redressing the individual harm to the dismissed employee but also by considering the broader infringement on general union activities. The goal is to eliminate such infringements and restore the normal collective labor-management order envisioned by the TUA.

III. The Core Issue: Deduction of Interim Earnings – Overruling Precedent

The Grand Bench then tackled the central question of deducting interim earnings from back pay:

(A) The Perspective of Individual Economic Loss:

- When an employee is unlawfully dismissed, they suffer individual economic harm by losing the wages they would have earned.

- However, dismissal also frees the employee from their obligation to work for the original employer, allowing them to utilize their labor capacity elsewhere.

- If the dismissed employee finds other employment and earns income, this interim income, to the extent it represents compensation for the use of labor capacity freed by the dismissal, is considered to have mitigated the economic loss from the dismissal.

- From this purely individual economic perspective, ordering the employer to pay back pay that includes amounts already compensated through interim earnings would go beyond restoring actual damages and would be an excessive remedy.

- The Court cautioned, however, that even from this individual perspective, a full, mechanical deduction of all interim income is not always appropriate. If the interim employment involved significantly heavier physical or mental burdens compared to the original job, ignoring this and simply deducting the gross interim earnings would be unreasonable as a form of victim relief.

(B) The Perspective of Remedying Harm to General Union Activities:

- The infringement on general union activities caused by a ULP dismissal arises from the "chilling effect" it has on other employees' willingness to engage in union activities.

- To eliminate this chilling effect, it is necessary to create a factual situation where the harm inflicted on the dismissed employee is effectively nullified, demonstrating that the ULP ultimately failed to achieve its suppressive objective.

- The decision on whether to deduct interim income, and the amount of such deduction, must also be made from this viewpoint. The restrictive effect on union activities is closely related to the severity of the actual impact of the dismissal on the individual employee. Factors such as the difficulty of re-employment, the nature and conditions of the interim job, and the amount of interim earnings all influence this impact.

- Therefore, when considering the removal of infringement on general union activities, these factors must be weighed to determine a remedy that is rationally necessary and appropriate to the degree of harm caused.

- The Court rejected the notion that back pay is an indispensable element of a remedy order irrespective of interim earnings, or that interim earnings should never be considered. Always ordering full back pay without any regard for interim income would lack rationality as a means of redress.

(C) The New Standard: Comprehensive Consideration and Overruling of Precedent:

- The Court mandated that Labor Commissions, when deciding on the necessity and amount of interim income deduction, must engage in a comprehensive consideration of both the individual economic loss aspect (A) and the harm to general union activities aspect (B).

- Failure to consider either aspect, or a lack of rationality in assessing the need for the remedy, would constitute an overstepping of discretionary limits, rendering the order illegal.

- With this, the Supreme Court explicitly declared that its 1962 Third Petty Bench judgment (the Showa 37 judgment) is overruled to the extent that it conflicts with this new "dual consideration" standard.

IV. Addendum: Critiquing One-Sided Approaches and Addressing Practical Concerns

The Court further elaborated:

- It rejected an alternative approach that would focus solely on the harm to general union activities when determining remedies. Such an approach, the Court argued, would unduly downplay the infringement on the dismissed employee's individual rights. A ULP dismissal inherently involves both individual disadvantageous treatment and an infringement on collective rights, and both aspects are relevant to the remedy.

- The remedies of reinstatement and back pay are directly tied to the harm suffered by the dismissed individual (loss of job, loss of wages) and cannot be determined without considering these personal elements.

- The Court also dismissed arguments that it would be too burdensome for Labor Commissions to consider interim income deductions, stating that Commissions can make such determinations by comprehensively evaluating submissions from both parties and the results of their own investigations.

V. Application to the Facts of the Daini Hato Taxi Case

Applying its newly established "dual consideration" framework to the facts at hand:

- Employees A et al. (taxi drivers) found employment as drivers with other taxi companies relatively quickly (ranging from the day after dismissal to about six months later) and earned income close to their previous wages.

- From the individual economic loss perspective, since the interim work was of the same nature (taxi driver), deduction of interim earnings should clearly be considered.

- From the perspective of harm to general union activities, given the relative ease of re-employment in the taxi industry at that time and the short period before re-employment, the impact of the dismissals on the individual employees and the consequent chilling effect on union activities within Company X were deemed comparatively minor.

- Considering these factors, the Court found that completely disregarding the interim income earned by Employees A et al. when ordering back pay, without any specific justification by the Labor Commission for doing so, lacked rationality.

- Since Commission Y had not provided any specific reasons for why deduction was unnecessary in this particular case, and no such reasons were apparent from the record, the back pay order was deemed to have exceeded the reasonable exercise of the Labor Commission's discretion.

VI. Conclusion on the Appeal

While the High Court's judgment was based on the reasoning of the now-overruled Showa 37 decision, its ultimate conclusion that the back pay order (which did not deduct interim income) was illegal was, in effect, correct under the new standard as well. Therefore, the Labor Commission's appeal was dismissed.

Dissenting Opinions:

It is important to note the presence of strong dissenting opinions. Justice Moriichi Kishi argued that interim income should generally not be deducted from back pay in ULP remedy orders, viewing it as an incidental benefit to the employee that is unrelated to the employer's primary duty to restore the status quo ante. He also differentiated the Japanese labor context from the U.S. one, where interim income deduction is standard.

A joint dissenting opinion by Justices Shigemitsu Dando, Yuzuru Homabayashi, Takaaki Hattori, and Shoichi Tamaki, while agreeing with the majority on the scope of Labor Commission discretion, argued that ULP remedies should be viewed solely from the perspective of rectifying harm to general union activities, not individual loss. From this viewpoint, they found the Labor Commission's decision not to deduct interim income in this case was not manifestly unreasonable.

Analysis and Significance

The Daini Hato Taxi Grand Bench decision is a landmark ruling with profound implications for unfair labor practice law in Japan:

- Overruling Precedent and Establishing a New Standard: The most direct significance is the explicit overruling of the 1962 Supreme Court (Third Petty Bench) precedent. In its place, the Grand Bench established the "dual consideration" framework, requiring Labor Commissions to weigh both individual employee damages and the broader impact on union activities when deciding on interim income deductions.

- Affirming Broad Labor Commission Discretion (with Limits): The judgment strongly supports the broad discretion of Labor Commissions in crafting ULP remedies, emphasizing that courts should defer to this expertise unless the Commission's decision is clearly unreasonable or an abuse of power. The PDF commentary notes that the Court’s language subtly shifted emphasis from merely "restoring the original state" to the broader goal of "recovering and ensuring a normal collective labor-management order."

- The "Dual Consideration" Framework in Practice: This framework requires a nuanced balancing act.

- Individual Harm: Generally leans towards deducting interim income to avoid overcompensation, but allows for non-deduction or partial deduction if the interim work was significantly more burdensome.

- Collective Harm (Chilling Effect): Considers the impact on union solidarity and activity. Non-deduction could be justified if it's deemed necessary to show that the ULP had no lasting negative consequence on the dismissed employee, thereby emboldening other union members. Factors include the difficulty of re-employment and the nature of the interim work.

- Critiques and Ongoing Debate:

- The PDF commentary highlights a significant academic critique: the factors considered under the "harm to general union activities" prong (difficulty of re-employment, nature of interim work, interim wage levels) largely overlap with those considered for "individual economic loss." This has led some scholars to argue that the second prong offers little distinct analytical value.

- The judgment (both majority and dissenting opinions) did not extensively delve into whether "union-specific damages" (e.g., loss of union membership, inability of the dismissed activist to continue their role at the original workplace) could justify non-deduction of interim income. The PDF suggests this might be due to the difficulty in linking such damages directly to the amount of interim income earned by the individual.

- Post-Daini Hato Developments:

- The PDF commentary mentions that subsequent Supreme Court cases, like Kyoto Awaji Kotsu (1977) and Akebono Taxi (1987), tended to find non-deduction orders illegal when the dismissed employee's individual impact was deemed minor, even downplaying the employer's anti-union intent as a factor for the interim income deduction specific question.

- Despite this, Labor Commissions, while formally applying the dual-consideration test, have in some instances continued to order full or near-full back pay by heavily emphasizing the severe impact of the ULP on the union itself (e.g., where the union was effectively destroyed).

Conclusion

The Daini Hato Taxi Grand Bench ruling reshaped the approach to back pay in unfair labor practice dismissal cases in Japan. By mandating a "dual consideration" of both individual harm and the collective impact on union activities when deciding on interim income deductions, the Supreme Court provided a more flexible and comprehensive framework than the stricter "restoration of original state" principle of its prior precedent. While affirming the broad discretion of Labor Commissions, it also set a standard of rationality, requiring them to justify decisions regarding interim income based on the specific facts and the twin goals of individual relief and restoration of healthy labor relations. The decision remains a cornerstone in ULP remedy jurisprudence, though its practical application and the weighing of its two prongs continue to be subjects of discussion and development in subsequent cases and Labor Commission practice.