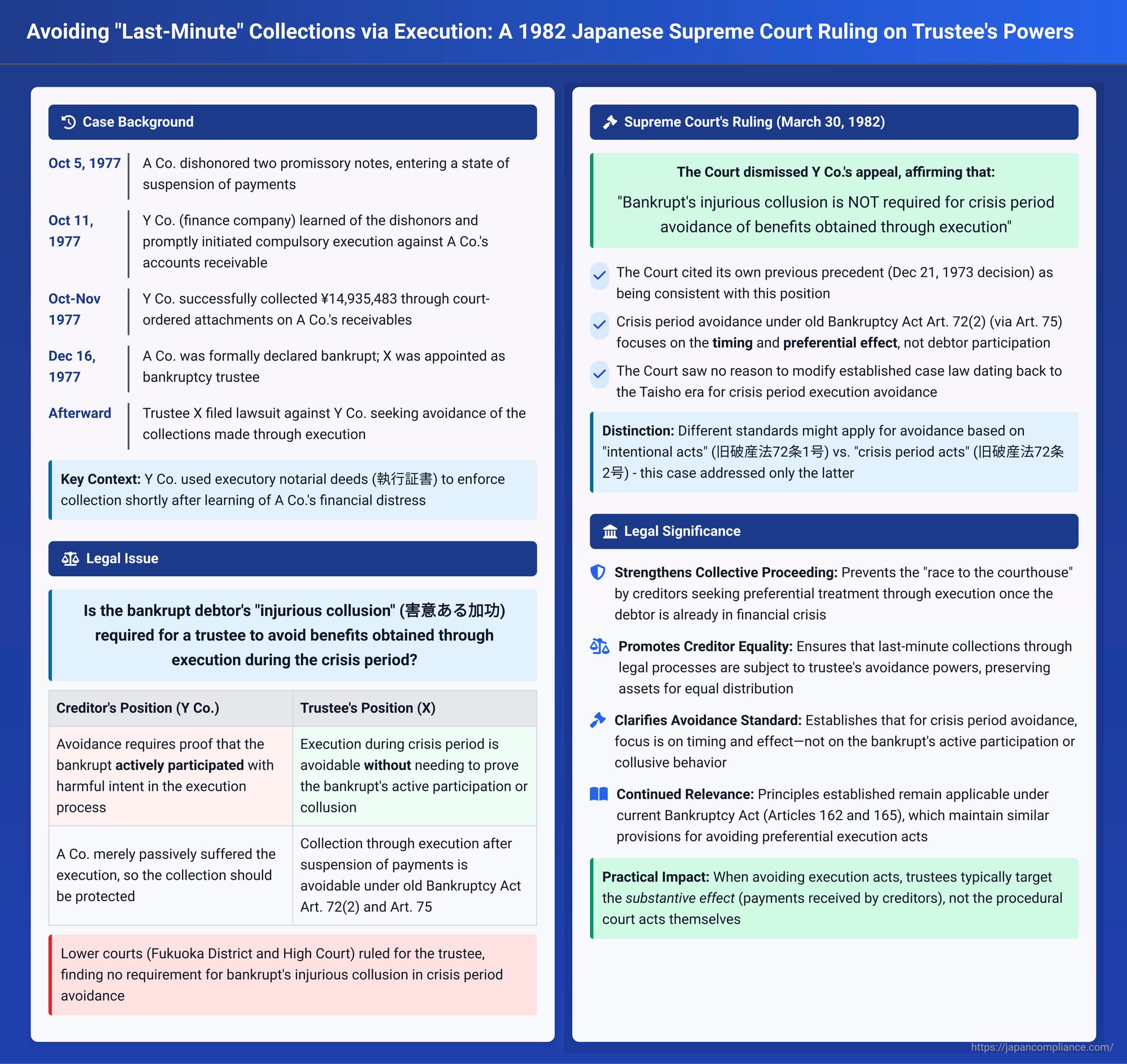

Avoiding "Last-Minute" Collections via Execution: A 1982 Japanese Supreme Court Ruling on Trustee's Powers

When a debtor is on the brink of bankruptcy, creditors may rush to collect on their claims through compulsory legal execution. A critical question in Japanese insolvency law is whether a bankruptcy trustee can later "avoid" (否認 - hinin, or deny the legal effect of) such collections if they occurred when the debtor was already in financial crisis. Specifically, does the trustee need to prove that the bankrupt debtor actively and with harmful intent colluded or participated in the creditor's execution efforts? A Supreme Court of Japan decision from March 30, 1982, provided a clear answer, particularly for avoidances based on the debtor's "crisis period."

Factual Background: Enforcement After Dishonor

The case involved A Co., which faced severe financial distress, evidenced by the dishonor of two of its promissory notes on October 5, 1977. Y Co., a finance company, was a creditor of A Co., holding claims based on five executory notarial deeds (執行証書 - shikkō shōsho), which are instruments that can be used directly for compulsory execution. An employee of Y Co. learned of A Co.'s note dishonors (a strong indication of suspension of payments).

Acting on prior instructions from Y Co., around October 11, 1977—shortly after the dishonors—the employee swiftly took action. Y Co. obtained court orders for the attachment and collection (差押および取立命令 - sashiosae oyobi toritate meirei) of A Co.'s accounts receivable owed by third parties, such as the city of Fukuoka. Through these execution measures, Y Co. successfully collected a total of 14,935,483 yen.

Subsequently, on December 16, 1977, A Co. was formally declared bankrupt under Japan's (then) old Bankruptcy Act. X was appointed as A Co.'s bankruptcy trustee. Trustee X then filed a lawsuit against Y Co. X argued that Y Co.'s collection of these receivables through compulsory execution constituted an act resulting in the extinguishment of A Co.'s debt to Y Co. that was avoidable by the trustee. The claim was based on Article 72, item 2, of the old Bankruptcy Act (which allowed for the avoidance of acts done during the debtor's "crisis period," such as after a suspension of payments, if detrimental to other creditors) read in conjunction with Article 75 of the same Act (which made the principles of Article 72 applicable to benefits obtained through execution acts).

In its defense, Y Co. contended that for a bankruptcy trustee to avoid satisfaction obtained through an execution act, it was a necessary requirement to prove that the bankrupt debtor (A Co.) had "injuriously colluded" or "actively participated with harmful intent" (害意ある加功 - gaiiaru kakō) in the creditor's enforcement process. Y Co. implied that since A Co. had merely suffered the execution passively, it was not avoidable.

The Fukuoka District Court (first instance) ruled in favor of trustee X. It held that "injurious collusion" by the bankrupt was not a prerequisite for avoiding an execution act under these particular avoidance provisions. The Fukuoka High Court (second instance) upheld this decision. The High Court found that Y Co.'s employee was aware of A Co.'s suspension of payments when initiating the execution, making it equivalent to Y Co. itself acting with such knowledge. It agreed with the first instance court that injurious collusion by the bankrupt was not a necessary element for this type of avoidance. Y Co. then appealed to the Supreme Court, reiterating its core argument that the bankrupt's injurious collusion was essential.

The Legal Issue: Is Bankrupt's "Injurious Collusion" Needed to Avoid Crisis-Period Execution Acts?

Japanese bankruptcy law, both under the old Act and the current one (e.g., current Bankruptcy Act Article 165), allows a trustee to avoid the satisfaction or benefit a creditor obtains through compulsory execution under certain circumstances, thereby recovering the value for the bankruptcy estate. The central dispute in this case was whether the specific type of avoidance being invoked by the trustee—"crisis period avoidance" under old Article 72, item 2, as applied to execution acts via Article 75—required proof that the bankrupt debtor had actively and with harmful intent participated in or facilitated the creditor's compulsory execution. If the debtor merely passively allowed the execution to proceed, would that shield the creditor's collection from the trustee's avoidance powers?

The Supreme Court's Ruling: No "Injurious Collusion" Required for Crisis Period Avoidance of Execution

The Supreme Court, in its judgment of March 30, 1982, dismissed Y Co.'s appeal. It firmly held that:

When an "act concerning the extinguishment of a debt" as described in Article 72, item 2, of the old Bankruptcy Act results from an "execution act" (as contemplated by Article 75 of that Act), it is NOT necessary for the bankrupt to have injuriously colluded in undergoing the compulsory execution for that act to be avoidable by the bankruptcy trustee.

The Court's reasoning was concise. It stated that this position was consistent with its own existing precedent, specifically citing a Supreme Court, Second Petty Bench decision from December 21, 1973 (Showa 48 (O) No. 544). The Court saw no compelling reason to depart from this established line of interpretation. Therefore, the High Court's judgment, which found Y Co.'s collection through execution to be avoidable under Article 72, item 2, without requiring proof of A Co.'s injurious collusion, was deemed correct and was upheld.

Context: Historical Treatment of Execution Act Avoidance

The PDF commentary accompanying this case provides valuable context on the historical treatment of avoiding execution acts under the old Bankruptcy Act, distinguishing between different types of avoidance claims:

- Intentional Avoidance (旧破産法72条1号 - kyūha 72-jō 1-gō; concerning acts by the bankrupt knowing they would harm creditors): When trustees sought to avoid execution acts under this "intentional avoidance" provision, older case law (Daishin'in and early Supreme Court) often did look for some form of active, intentional involvement or facilitation by the bankrupt in the execution process. For instance, the bankrupt might have, with fraudulent intent, invited or colluded in the execution. The commentary suggests a judicial tendency to require such active participation by the bankrupt for this specific type of avoidance. (It is important to note, as the commentary points out, that these older precedents concerning intentional avoidance of preferential execution acts have largely lost their direct precedential value under the current Bankruptcy Act. The current Act's main "intentional fraudulent act avoidance" provision, Article 160(1), primarily targets asset-decreasing acts, while preferential acts are mainly dealt with under Article 162, which has different criteria).

- Crisis Period Avoidance (旧破産法72条2号 - kyūha 72-jō 2-gō; concerning acts done after suspension of payments or bankruptcy petition, detrimental to creditors): This was the provision directly relevant to the 1982 Supreme Court judgment. For this category of avoidance, a consistent line of judicial precedent, dating back to the Taisho era (1912-1926), had established that satisfaction obtained by a creditor through compulsory execution after the debtor had already suspended payments (i.e., during the "crisis period") could be avoided by the trustee without needing to prove any active or injurious participation or collusion by the bankrupt. The mere fact that the creditor obtained satisfaction through execution during this critical period, when other conditions for avoidance (such as the creditor's knowledge of the suspension of payments and the detrimental effect on other creditors) were met, was sufficient. The bankrupt debtor merely suffering the execution did not shield the resulting satisfaction from avoidance.

The 1982 Supreme Court decision at issue firmly placed itself within this latter, well-established line of precedent for "crisis period avoidance" of execution acts, confirming that the bankrupt's active collusion was not a necessary element.

Implications for Current Bankruptcy Law (Primarily Articles 162 & 165)

The principles derived from this line of "crisis period avoidance" cases concerning execution acts, as affirmed by the 1982 Supreme Court, remain highly relevant for interpreting the corresponding provisions of the current Japanese Bankruptcy Act.

- The current Bankruptcy Act, in Article 162, allows for the avoidance of preferential acts (e.g., payments or granting of security for existing debts) made when the debtor was insolvent or after they suspended payments.

- Article 165 of the current Act explicitly makes the provisions for avoiding such preferential acts (Article 162) applicable to situations where a creditor obtains satisfaction through an execution act.

Therefore, the 1982 Supreme Court ruling supports the interpretation under current law that if a creditor obtains payment or other satisfaction via compulsory execution after the debtor has become insolvent (or has suspended payments, which triggers a presumption of insolvency for the purposes of Article 162), the bankruptcy trustee can typically seek to avoid that satisfaction as a preferential act. Crucially, the trustee would not need to prove any specific injurious collusion or harmful intent on the part of the bankrupt debtor in the execution process itself. The primary focus is on the timing of the execution relative to the debtor's financial crisis and the resulting preferential effect that harms the principle of creditor equality.

It is also important to understand, as the PDF commentary clarifies, that when an execution act is avoided, what the trustee typically targets is the substantive effect of that execution – namely, the payment or satisfaction received by the creditor. The avoidance action does not usually seek to nullify the procedural acts of the court or the execution officer (e.g., a court bailiff) who carried out the execution.

Concluding Thoughts

The Supreme Court's March 30, 1982, judgment delivered a clear and important message: for the purpose of avoiding benefits that creditors obtain through compulsory execution during a debtor's financial crisis period (specifically, after a suspension of payments), the active and harmful participation or "injurious collusion" of the bankrupt debtor in that execution process is not a necessary element for the trustee's avoidance claim to succeed. This ruling ensures that creditors cannot unfairly benefit from a "race to the courthouse" to enforce their claims through coercive execution measures once a debtor is already effectively insolvent or has signaled their inability to pay debts generally. By allowing trustees to recover such last-minute preferential satisfactions obtained via execution, even if the debtor passively allowed the execution to proceed, the decision strongly reinforces the fundamental bankruptcy principle of ensuring equitable treatment among all creditors.