Attribution of Foreign Subsidiary Losses: A Japanese Supreme Court Perspective

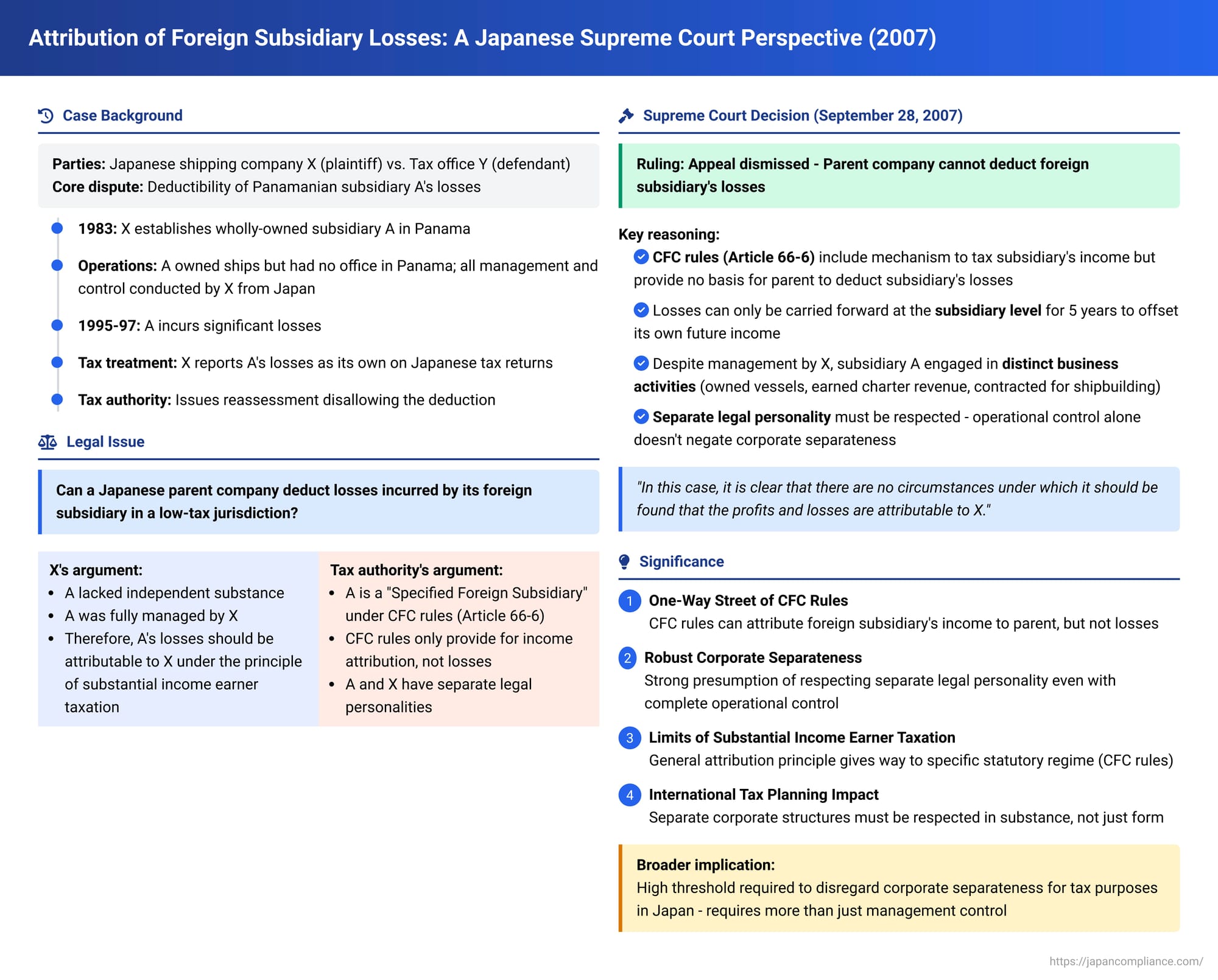

Case: Judgment of the Supreme Court, Second Petty Bench, September 28, 2007 (Case No. 2005 (Gyo-Hi) No. 89: Action for Rescission of Reassessment Disposition of Corporation Tax, Consumption Tax, and Local Consumption Tax)

Introduction

On September 28, 2007, the Supreme Court of Japan delivered a significant judgment concerning the attribution of losses incurred by a foreign subsidiary to its Japanese parent company for corporate income tax purposes. The case explored the intricate relationship between Japan's anti-tax haven legislation (specifically, Article 66-6 of the Act on Special Measures Concerning Taxation, commonly known as Controlled Foreign Company or CFC rules) and the fundamental principle of separate legal personality in corporate taxation. This ruling provides crucial insights into how Japanese tax law treats losses generated by subsidiaries in low-tax jurisdictions and the conditions under which income and losses are attributed to distinct legal entities.

The central issue was whether a Japanese parent company, X, could deduct losses incurred by its wholly-owned Panamanian subsidiary, A, when calculating its own taxable income. X argued that since A was essentially managed and controlled by X and lacked independent substance, A's losses should be considered X's losses. The tax authority, Y, contended that under the CFC rules, such attribution was not permissible and that the losses belonged solely to the subsidiary, A.

Facts of the Case

X, a Japanese corporation engaged in the shipping industry, established A as a wholly-owned subsidiary in Panama in June 1983. From its inception, A did not maintain a physical office in Panama. All incorporation documents, business records, and operational papers were stored at X’s office in Japan. Furthermore, the management, control, and operation of A's business activities were entirely conducted by X.

Consistent with this operational integration, X had, since A’s establishment, treated all of A’s assets, liabilities, profits, and losses as belonging to X for the purposes of filing its Japanese corporate income tax and consumption tax returns.

During the fiscal years ending in July of 1995, 1996, and 1997 (hereinafter referred to as "the fiscal years in question"), A incurred significant losses. X, following its established practice, reported these losses as its own, thereby reducing its taxable income in Japan.

The Chief of the Imabari Tax Office, Y, challenged this treatment. Y asserted that A fell under the definition of a "Specified Foreign Subsidiary, etc." (特定外国子会社等) as stipulated by Article 66-6 of the Act on Special Measures Concerning Taxation (the "CFC Rules"). Consequently, Y argued that any losses incurred by A could only be addressed within the framework of the CFC Rules and could not be directly deducted by X for Japanese corporate tax purposes. Y issued a corrective reassessment (Kosei Shobun) to X, disallowing the deduction of A’s losses and imposing underpayment penalties. X disputed this reassessment, initiating administrative appeals and subsequently filing a lawsuit to have the reassessment revoked.

Procedural History

The Matsuyama District Court initially ruled in favor of X. The District Court held that Article 66-6 of the Act on Special Measures Concerning Taxation did not prohibit the attribution of losses from a Specified Foreign Subsidiary to a domestic parent company if the subsidiary essentially lacked substance and its operations were entirely controlled by the parent.

However, Y appealed this decision. The Takamatsu High Court overturned the District Court's ruling. The High Court found that where the CFC Rules (Article 66-6) are applicable, the specific provisions of that article must be followed. It asserted that the CFC Rules create a mandatory framework for dealing with the income (and implicitly, the losses) of such subsidiaries, leaving no room for the application of the general principle of substantial income earner taxation (実質所得者課税の原則 – Article 11 of the Corporation Tax Act) to re-attribute the subsidiary's losses to the parent. The High Court, therefore, dismissed X’s claim.

X, dissatisfied with the High Court's judgment, lodged a final appeal with the Supreme Court of Japan.

The Supreme Court's Decision

The Supreme Court, on September 28, 2007, dismissed X’s appeal, upholding the High Court's decision in favor of the tax authority, Y. The Court’s reasoning focused on two main areas: the interpretation and application of Article 66-6 of the Act on Special Measures Concerning Taxation, and the factual determination of to whom the losses of A should be attributed.

Interpretation of Article 66-6 (CFC Rules)

The Supreme Court began by elaborating on the purpose and mechanics of Article 66-6 of the Act on Special Measures Concerning Taxation (all references to legislative provisions are to those in effect at the time of the relevant fiscal years, as noted in the judgment).

- Purpose of the CFC Rules: Article 66-6, Paragraph 1, provides that if a domestic corporation has a direct or indirect ownership stake exceeding 50% in a foreign affiliated company (defined in Article 66-6(2)(1)) located in a country or territory with significantly lower corporate income tax rates than Japan (a "Specified Foreign Subsidiary, etc."), and if that subsidiary has "Applicable Retained Earnings" (適用対象留保金額), then an amount corresponding to the domestic corporation's shareholding in those retained earnings is to be included in the domestic corporation's gross revenue (益金の額に算入する) for Japanese corporate income tax purposes.The Court affirmed that the objective of this provision was to address instances where Japanese corporations established subsidiaries in low-tax jurisdictions to conduct economic activities and allowed profits to accumulate in those subsidiaries, thereby deferring or avoiding Japanese taxation. The CFC Rules were designed to counteract such tax avoidance strategies and ensure substantial tax fairness by clearly defining the taxation requirements and enhancing the stability of tax enforcement.

- Treatment of Losses under CFC Rules: The Court emphasized a critical distinction: while the CFC Rules provide a mechanism for taxing the retained income of a Specified Foreign Subsidiary in the hands of its Japanese parent, they do not contain any provision allowing the Japanese parent to deduct losses incurred by such a subsidiary. The Court stated that it is clear from Article 22, Paragraph 3, of the Corporation Tax Act that losses incurred by a Specified Foreign Subsidiary are not includable in the deductible expenses (損金の額に算入されない) of the domestic parent company.

- Subsidiary-Level Loss Carry-Forward: The Court then pointed to Article 66-6, Paragraph 2, Item 2 of the Act on Special Measures Concerning Taxation. This provision (which corresponds to Article 66-6(2)(4) in later versions of the law) stipulated that the "undisposed income" (未処分所得の金額) of a Specified Foreign Subsidiary was to be calculated based on its financial statements, adjusted for losses incurred within the five years preceding the commencement of the current fiscal year. In other words, the subsidiary itself was permitted to carry forward its losses for five years to offset its own future undistributed income.The Supreme Court interpreted this loss carry-forward provision at the subsidiary level as a measure designed to maintain equilibrium with the rule that includes the subsidiary's retained income in the parent's taxable income. This implied that the tax system recognized and dealt with the subsidiary's losses at the level of the subsidiary itself.

- No Basis for Parent Company Deduction: Consequently, the Court concluded that if a Specified Foreign Subsidiary incurs a loss, the law only permits that loss to be carried forward for a maximum of five years and deducted from that same subsidiary's undistributed income in subsequent fiscal years. The fact that the parent company might be subject to Japanese tax on the subsidiary's income under Article 66-6, Paragraph 1, does not, in reverse, mean that the parent company can deduct the subsidiary's losses when calculating its own taxable income. Such a deduction, the Court found, cannot be inferred from the structure or purpose of Article 66-6.

Factual Attribution of A's Activities and Losses

Beyond the interpretation of the CFC Rules, the Supreme Court also examined the factual basis for attributing the losses. It referred to the facts as lawfully established by the High Court:

- A was, during the fiscal years in question, a Specified Foreign Subsidiary of X.

- A did not have an office in Panama, its place of incorporation.

- The management, control, and operation of A's business were carried out by X.

- A did not satisfy the conditions for exemption from the CFC Rules (e.g., requirements related to active business conduct, fixed facilities, local management, etc., as stipulated in Article 66-6, Paragraph 3, at the time).

However, crucially, the High Court also found that:

- A owned vessels registered under the Panamanian flag.

- A had procured funds from X and, acting as the principal, had entered into shipbuilding contracts.

- A earned revenue from chartering these vessels.

- A incurred expenses, including the employment of seafarers.

Based on these findings, the Supreme Court concluded that A, despite being managed by X, was engaged in its own distinct business activities as a separate legal entity. The Court stated that, "In this case, it is clear that there are no circumstances under which it should be found that the profits and losses are attributable to X." Therefore, for the fiscal years in question, the profits and losses legally accrued to A, and it was A that incurred the losses.

As a result, X could not deduct A's losses when calculating its own corporate income. The Supreme Court thus affirmed the High Court's judgment, which had found the tax authority's reassessment and imposition of underpayment penalties to be lawful.

The Supplementary Opinion

One of the justices provided a supplementary opinion to further elaborate on the legal principles underpinning the decision, particularly concerning corporate personality and the attribution of profits and losses.

- Primacy of Separate Legal Personality: The supplementary opinion began by emphasizing that a corporation is, by law, recognized as an entity to which profits and losses arising from its business activities are to be attributed. This principle holds true, the opinion asserted, even in cases where a corporation, from a management or operational perspective, effectively functions as a business division of another corporation. The mere fact of economic integration or control by a parent does not, in itself, negate the separate legal and tax status of the subsidiary.

- Nature of Article 66-6: The opinion clarified that Article 66-6 of the Act on Special Measures Concerning Taxation, which deals with Specified Foreign Subsidiaries, does not operate by treating the individual profits and losses from the subsidiary's activities as if they inherently belong to the Japanese parent company. Instead, the CFC Rules are structured to first calculate the undistributed income of the subsidiary based on its own profit and loss accounts. Then, a portion of this undistributed income, corresponding to the parent company's shareholding, is included in the parent's taxable income. This mechanism, the opinion noted, is evident from the plain language of the statute.

- Underlying Assumption: This statutory approach presupposes the fundamental understanding that profits and losses from a corporation's business activities are primarily attributed to that corporation. Article 66-6 is a special measure, taking into account the foreign status of the subsidiary, but it builds upon, rather than overrides, this basic principle of profit/loss attribution to the entity conducting the activities.

- Application to the Case: Applying this to the present case, the supplementary opinion stated that, based on the facts lawfully established by the High Court, even if all decisions regarding A's vessel ownership and operations were made by X, these activities were legally the business activities of A. Consequently, the profits and losses arising from these activities belonged to A, not to X. The CFC Rules' purpose and structure, according to the supplementary opinion, reinforce this conclusion by providing specific measures for how a parent company is taxed on its share of a foreign subsidiary's income, rather than by allowing a general re-attribution of all the subsidiary's financial results.

Analysis and Implications

The Supreme Court's decision in this case, along with the supplementary opinion, offers several important takeaways regarding Japanese tax law, particularly concerning CFC rules and the principle of corporate separateness.

The Nature of Anti-Tax Haven (CFC) Rules

This case underscores the specific, and often limited, scope of CFC rules. These rules, present in Japan since 1978 and significantly amended over the years (including major revisions influenced by international initiatives like the OECD/G20 Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) project), are primarily designed to prevent the deferral of taxation on passive or artificially shifted income accumulated in low-tax jurisdictions. They achieve this by attributing a portion of the CFC's income to its domestic shareholders.

The Supreme Court's judgment makes it clear that these rules, at least as they existed at the time and in their fundamental structure, are a one-way street in terms of income attribution for the parent: they can cause inclusion of subsidiary income in the parent's tax base, but they do not provide a corresponding mechanism for the parent to deduct subsidiary losses. The provision allowing the subsidiary to carry forward its own losses further reinforces that the losses are considered to belong to the subsidiary entity. This is a common feature in many CFC regimes globally.

The Principle of Substantial Income Earner Taxation vs. Specific Statutory Regimes

The "Principle of Substantial Income Earner Taxation" (実質所得者課税の原則), sometimes equated with a substance-over-form doctrine, generally allows tax authorities to look beyond the legal form of a transaction or entity to tax the party that economically benefits from or bears the burden of income or loss.

The High Court in this case had taken a firm stance: where Article 66-6 applies, its specific provisions are mandatory and leave no room for the application of the general principle of substantial income earner taxation to re-attribute losses. The Supreme Court, while upholding the High Court's conclusion, did so primarily by finding that, factually, the losses belonged to A as a separate operating entity, and that Article 66-6 did not permit X to deduct them. The Supreme Court did not explicitly state that the principle of substantial income earner taxation is always excluded when CFC rules are potentially applicable. However, its factual determination that A had its own activities and that there were "no circumstances" to attribute its P&L to X suggests that a very high threshold would need to be met to disregard a subsidiary's separate existence for loss attribution purposes, even outside the direct application of CFC income inclusion rules.

The supplementary opinion strongly suggests that the default position is to respect the legal form and attribute profits and losses to the entity that legally undertook the activities.

Strength of Separate Legal Personality in Japanese Tax Law

The supplementary opinion, in particular, champions a robust view of separate legal personality. It asserts that even if a subsidiary is "in substance" merely a business division of its parent from a management perspective, this does not automatically mean its profits and losses are attributable to the parent. For tax purposes, the legal entity that conducts the business is the primary subject of profit and loss attribution, unless "special circumstances" warrant a different treatment. The judgment does not elaborate extensively on what such "special circumstances" might entail beyond the facts of this case, but the implication is that mere control or operational integration by the parent is insufficient.

This has broader implications: if it is difficult to attribute a subsidiary's losses to a parent, it would logically also be difficult to attribute a subsidiary's profits to a parent based solely on the principle of substantial income earner taxation, especially if the subsidiary is not covered by CFC rules (e.g., if it is in a high-tax jurisdiction or meets active business exemptions). In such cases, a strong argument would be needed to demonstrate that the subsidiary is a mere shell or conduit with no independent economic role, going beyond the level of integration described in this case. The court's emphasis on A engaging in its own activities (owning vessels, contracting for shipbuilding, earning charter revenue, hiring crew) was key to recognizing it as the entity to which profits and losses accrued, despite X's overall management and control.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's decision in the case of X reaffirms the distinct treatment of foreign subsidiary income and losses under Japan's CFC rules. While these rules can lead to the inclusion of a subsidiary's retained income in the parent's tax base, they do not permit the parent to deduct the subsidiary's losses. The judgment, particularly the supplementary opinion, strongly upholds the principle of separate legal personality, indicating that profits and losses are generally attributed to the corporate entity that legally conducts the underlying business activities. For a parent company to claim its subsidiary's losses, or for tax authorities to attribute a subsidiary's profits to a parent outside the specific scope of CFC rules, exceptional circumstances going beyond mere parental control and operational integration would likely need to be demonstrated. This case serves as a critical reminder of the importance of respecting corporate forms in international tax planning and the specific, often narrowly defined, scope of anti-avoidance provisions.