ATM Robbery: When Your Passbook and a Guessed PIN Empty Your Account, Who Foots the Bill in Japan?

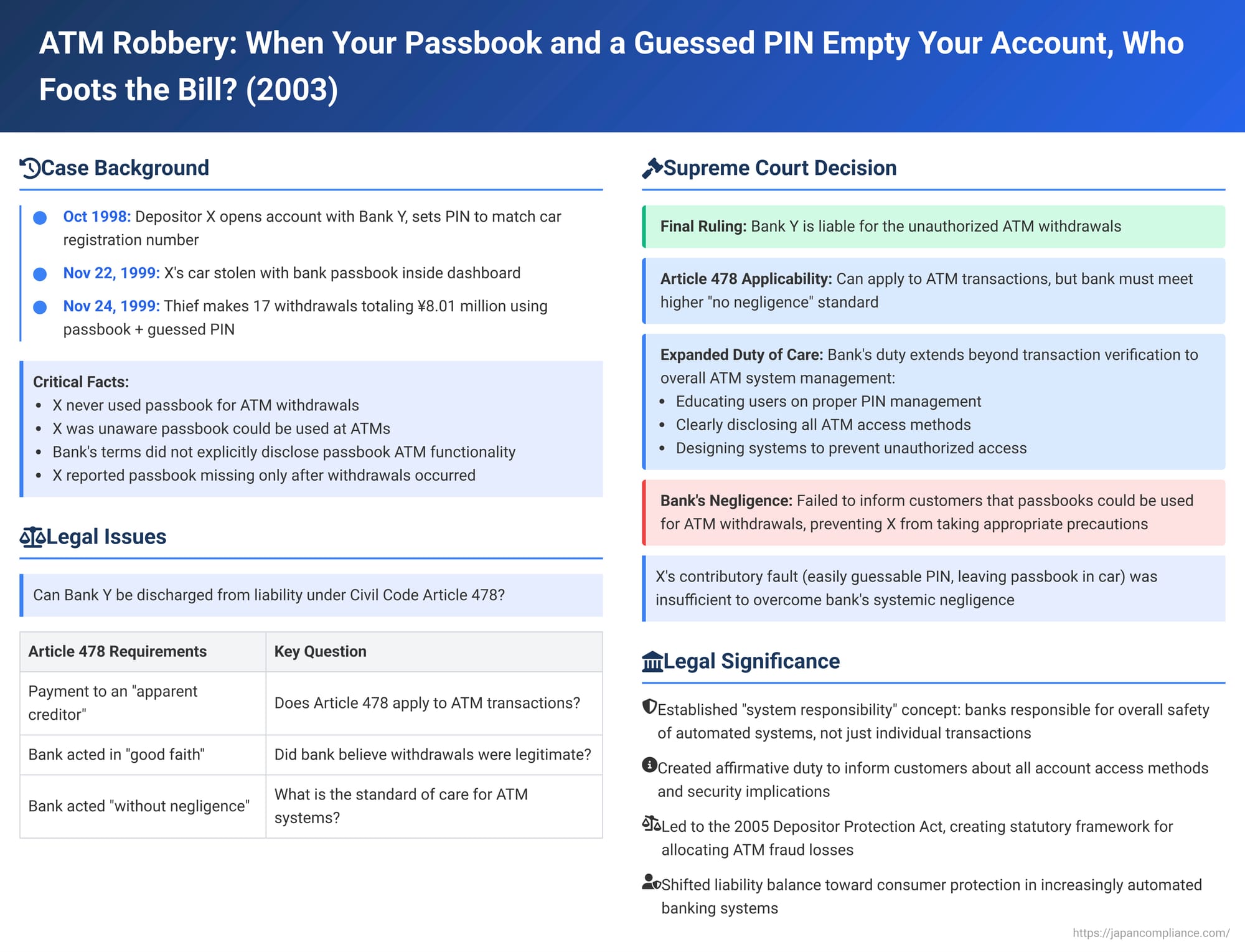

Automated Teller Machines (ATMs) offer undeniable convenience, but they also open avenues for unauthorized access to bank accounts. A pivotal Japanese Supreme Court decision on April 8, 2003 (Heisei 14 (Ju) No. 415), addressed a scenario where a thief, using a stolen bank passbook and a cleverly guessed PIN, drained a significant sum from a depositor's savings account via ATM. The case hinged on whether the bank could be absolved of liability under (former) Civil Code Article 478, which protected those who made payments to an "apparent creditor" in good faith and without negligence, and importantly, it scrutinized the bank's broader responsibilities in managing its ATM systems.

Paying the "Apparent" Creditor: The Shield of Civil Code Article 478

At the time of this case, Article 478 of the Japanese Civil Code (since revised in wording but similar in core principle) provided a defense for a debtor (like a bank owing a deposit) if they made a payment. If the payment was made to someone who wasn't the true creditor but had the "outward appearance of being entitled to receive payment" (a "quasi-possessor of the claim" or saiken no jun-senyūsha), the debtor was discharged from their obligation, provided they acted in good faith (believing the recipient was the true creditor) and without negligence. This aimed to protect the safety of transactions where appearances could be legitimately misleading.

Facts of the 2003 Case: Stolen Car, Stolen Passbook, Guessed PIN

The unfortunate chain of events unfolded as follows:

- The Account and PIN: X (the plaintiff depositor) held a savings account with Y (the defendant bank). This account allowed ATM withdrawals using either a cash card or the passbook combined with a PIN. When opening the account and applying for a cash card in October 1998, X chose a PIN identical to the 4-digit registration number of X's own car.

- Depositor's ATM Usage and Awareness: X had used the cash card for ATM deposits but had never made ATM withdrawals using either the card or the passbook. Crucially, X was unaware that ATM withdrawals could even be made using just the passbook and PIN ("passbook machine withdrawal" or tsūchō kikai harai).

- The Theft: On the evening of November 22, 1999, X left the car parked near home with the bank passbook stored in the dashboard. By the next morning, the car had been stolen, and with it, the passbook.

- Unauthorized ATM Withdrawals: On November 24, 1999, between 8:52 AM and 9:56 AM, an unauthorized individual made 17 withdrawals from X's account at ATMs in several of Y bank's branches. These withdrawals, totaling 8.01 million yen, were all made using X's stolen passbook and the PIN (which the thief presumably deduced from the car's registration number, given the car was also stolen).

- Bank's Terms and Reporting Delay: Y bank's regulations for cash card usage mentioned card-based ATM withdrawals and included an exemption clause stating the bank would generally not be liable for unauthorized card withdrawals if the card's authenticity and the correct PIN were verified. However, neither the savings deposit regulations nor the card regulations explicitly stated that passbook-based ATM withdrawals were possible, nor was there any specific exemption clause covering such withdrawals. X reported the car theft on November 23 but only realized the passbook was also missing later. The passbook loss was reported to the bank after the unauthorized withdrawals had already occurred.

- Lower Court Rulings: Both the first instance and appellate courts dismissed X's claim for the return of the money, finding that the bank's payout via ATM was valid under Civil Code Article 478 because the thief presented the genuine passbook and correct PIN, giving the appearance of a rightful transaction. X appealed.

The Supreme Court's Ruling: Bank Held Negligent for Systemic Failings

The Supreme Court overturned the lower courts' decisions and ruled in favor of X, the depositor, ordering the bank to repay the withdrawn amount plus interest. The Court's reasoning was multi-faceted:

- Article 478 CAN Apply to ATM Withdrawals: The Court first affirmed that Article 478 could, in principle, apply to unauthorized ATM withdrawals. The fact that ATM transactions are non-face-to-face does not automatically preclude the application of this provision.

- A Higher Standard for Bank's "No Negligence" in ATM Systems: This was the crucial part of the judgment. For a bank to successfully claim it was "without negligence" under Article 478 in the context of an unauthorized ATM withdrawal, it's not enough that the ATM correctly verified the physical token (passbook or card) and the PIN at the moment of the transaction. The bank must also demonstrate that it fulfilled its duty of care concerning the overall installation and management of its entire ATM withdrawal system. This broader duty includes:

- Taking measures to ensure depositors understand how to manage their PINs and other security credentials properly.

- Clearly informing depositors about all available methods of ATM withdrawal (e.g., that withdrawals can be made using a passbook and PIN).

- Designing and operating the system to exclude unauthorized withdrawals to the fullest extent possible.

The Court reasoned that because ATM withdrawals are mechanical and lack the human oversight of counter transactions (where staff can observe behavior and make further checks), the systemic safeguards and depositor education provided by the bank become paramount in assessing its diligence.

- Bank Was Negligent in This Specific Case:

- Y bank had implemented a system allowing ATM withdrawals using just a passbook and PIN. However, it failed to explicitly state this functionality in its card regulations, savings deposit regulations, or otherwise clearly inform its depositors, including X, about this withdrawal method. X was, as a result, unaware that such withdrawals were possible.

- The Court emphasized that to prevent unauthorized access, depositors must be made aware that their passbook and PIN can be used for ATM withdrawals, so they understand the importance of diligently managing both. A bank offering such a system has a duty to clearly disclose this.

- Y bank's failure to do so constituted a breach of its duty of care in the installation and management of its passbook ATM withdrawal system. Therefore, the bank was negligent with respect to the unauthorized withdrawals.

- Depositor's Contributory Fault: The Court acknowledged that X also bore some responsibility: choosing a PIN that was easily guessable (the car's registration number) and leaving the passbook in the car's dashboard, which facilitated both the theft of the passbook and the inference of the PIN.

- Bank's Systemic Negligence Prevailed: However, the Supreme Court concluded that X's degree of contributory fault was not sufficient to overturn the finding that Y (the bank) was primarily negligent due to its systemic failures in disclosure and management.

- Since the bank was found negligent, the conditions for protection under Article 478 were not met, and the unauthorized withdrawals did not validly discharge the bank's debt to X.

Significance: A New Standard of Care for Automated Banking

This 2003 Supreme Court decision was a landmark in consumer protection within the context of increasingly automated banking services.

- Beyond Transaction-Level Verification: The judgment significantly shifted the focus of a bank's duty of care. It's not merely about whether the ATM correctly processed a card/passbook and PIN during a specific transaction; banks have broader responsibilities for the overall safety, security, and transparency of their automated banking systems.

- The Duty to Inform and Educate Customers: A key takeaway is the bank's affirmative duty to clearly inform customers about all methods by which their accounts can be accessed via ATMs and the associated security implications. Lack of such disclosure can be deemed negligence.

- Systemic Responsibility: Banks must ensure their ATM systems, as a whole, are designed and operated to minimize the risk of unauthorized access, including robust user education on PIN security and management of access tokens like passbooks and cards.

The Depositor Protection Act (Enacted After This Judgment)

It's important to note that after this Supreme Court ruling, Japan enacted the "Act on the Protection of Depositors and Savings Customers from Unauthorized Automated Teller Machine Withdrawals, etc." (commonly known as the "Depositor Protection Act") in 2005. This Act provides a specific framework for allocating losses in cases of unauthorized ATM withdrawals.

- For instance, in cases of withdrawals using a stolen card or passbook (similar to the facts here), the Act generally makes financial institutions liable for compensating the depositor for the loss.

- However, the Act also allows for a reduction in the bank's liability if the depositor was negligent (e.g., using an easily guessable PIN like a birthdate, or writing the PIN on the card/passbook). In such cases of depositor negligence (but not gross negligence), the bank's compensation might be limited to three-quarters of the withdrawn amount.

- If the depositor was grossly negligent or acted with willful misconduct, the bank might be entirely exempt from liability.

- Crucially, the Depositor Protection Act's provisions often still require the bank itself to have been acting in good faith and without negligence for its own protections or limitations on liability to apply. Therefore, the high standards of systemic care for banks established by the 2003 Supreme Court judgment (regarding system safety and depositor information) remain highly relevant. If a bank is found to have been negligent under these Supreme Court standards, the depositor's own contributory fault might not reduce the bank's liability as much as it otherwise might under the Act, or potentially not at all.

Broader Relevance

The principles articulated in this case concerning "system responsibility"—the idea that entities providing automated systems have a duty to ensure their overall safety and inform users of risks—could potentially be applied to other types of automated service systems beyond just banking ATMs.

Conclusion

The 2003 Supreme Court decision was a significant victory for bank depositors and a clear message to financial institutions. It established that in the age of automated banking, a bank's responsibility extends beyond the mere mechanical verification of a card/passbook and PIN at the ATM. Banks must ensure the overall safety, security, and transparency of their electronic banking systems, which includes adequately informing customers about all functionalities and associated risks. Failure to meet this heightened duty of care can render a bank liable for unauthorized withdrawals, even if the depositor also bears some degree of fault. This ruling, along with the subsequent Depositor Protection Act, has helped to shape a more balanced approach to allocating losses from ATM fraud in Japan.