Future Medical Fees as Collateral: Japan’s Supreme Court Validates Long‑Term Receivables Assignment (1999)

TL;DR

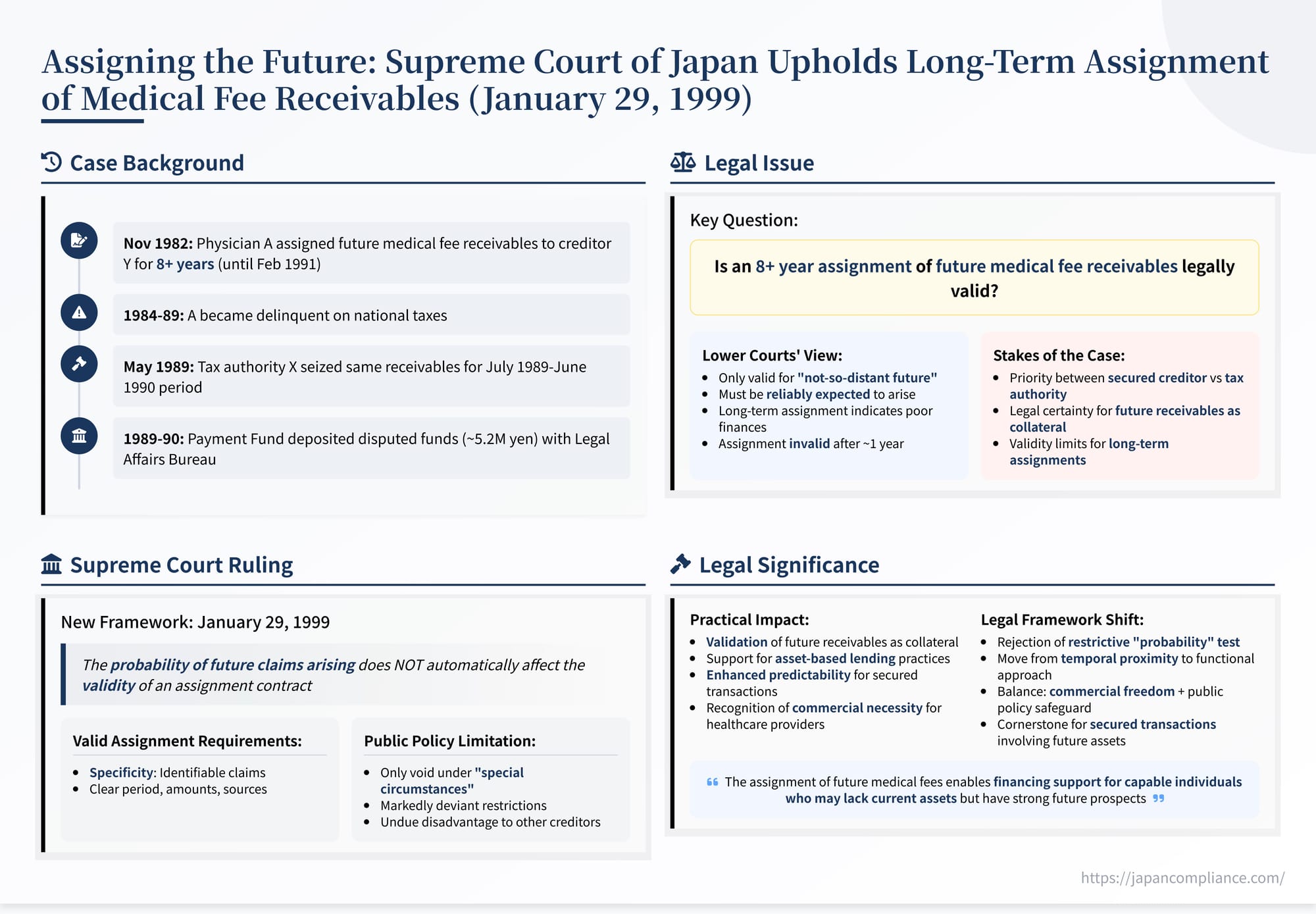

The 1999 Supreme Court decision confirmed that long‑term assignments of future medical‑fee receivables are valid if (i) the claims are specifically identified and (ii) no special circumstances render the contract contrary to public policy. The ruling rejected lower‑court tests that hinged on the probability of the claims arising or on one‑year temporal limits, thereby bolstering asset‑based lending in Japan.

Table of Contents

- Factual Background: A Long‑Term Assignment Meets a Tax Lien

- The Core Dispute and Lower Court Decisions

- The Supreme Court’s Analysis: A New Framework for Future Claim Assignments

- Judgment and Implications

- Conclusion

On January 29, 1999, the Third Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan delivered a landmark decision in a case concerning the confirmation of a right to claim deposited funds (1997 (O) No. 219). This ruling significantly clarified the legal principles governing the assignment of future receivables under Japanese law, particularly focusing on the validity of long-term assignments of medical fees generated through the social insurance system. The Court addressed the conflict between a creditor who had taken an assignment of future fees as security and a subsequent tax lien asserted by the government, ultimately favoring the validity of the assignment unless specific public policy concerns were present. This analysis explores the intricate factual background, the legal arguments presented, the lower courts' reasoning, and the Supreme Court's definitive framework for assessing the validity of future claim assignments.

Factual Background: A Long-Term Assignment Meets a Tax Lien

The case involved several parties and a complex sequence of events:

- The Debtor and the Assignment: A, a physician operating a clinic, entered into a contract with a creditor company, Y, on November 16, 1982. The purpose of this contract was to secure the repayment of A's debt to Y. Under the agreement, A assigned to Y specific portions of the future medical fee receivables (診療報酬債権 - shinryō hōshū saiken) that A expected to receive from the Social Insurance Medical Fee Payment Fund (hereinafter "the Fund") over a period spanning from December 1, 1982, to February 28, 1991 – a duration of over eight years. The contract specified the exact monthly amount to be assigned, totaling approximately 79.5 million yen over the entire period. Crucially, A notified the Fund of this assignment using a certificate with a certified date (確定日付のある証書 - kakutei hizuke no aru shōsho) on November 24, 1982. This notification is a critical step under the Japanese Civil Code for an assignment to be effective against third parties, including the debtor (the Fund).

- Tax Delinquency: Subsequently, between June 1984 and March 1989, A became delinquent on various national taxes.

- Tax Authority's Seizure: On May 25, 1989, the Director of the Sendai National Tax Bureau, acting on behalf of the State (hereinafter X), took action to collect the unpaid taxes. X issued a seizure order against the medical fee receivables that A was due to receive from the Fund during the period from July 1, 1989, to June 30, 1990. This period fell within the timeframe covered by A's prior assignment to Y. The Fund received notification of this tax seizure on the same day, May 25, 1989.

- Deposit of Funds: Faced with competing claims to the same funds – Y claiming entitlement based on the prior assignment and X claiming entitlement based on the tax seizure – the Fund resorted to a legal procedure called kyōtaku (供託). Between July 1989 and June 1990, the Fund deposited the disputed fee payments (totaling approximately 5.2 million yen) with the relevant Legal Affairs Bureau (Akita District Legal Affairs Bureau, Noshiro Branch), naming both A and Y as potential rightful recipients. This deposit effectively discharged the Fund's obligation, shifting the dispute over entitlement to the deposited funds between Y and X (representing A's tax liability).

- Seizure of Deposit Refund Right: Following the deposit, X took a further step. Between October 1989 and August 1990, X sequentially seized A's right to claim the refund of these deposited funds from the deposit office. Notices of these seizures were served on the deposit officer.

The Core Dispute and Lower Court Decisions

The legal battle then centered on who – the initial assignee Y or the tax authority X – had the superior claim to the deposited funds. X initiated a lawsuit against Y, seeking a declaratory judgment confirming X's right to collect the deposited funds based on its seizure of A's refund claim right.

X's central argument was that the original assignment agreement between A and Y was partially invalid. Specifically, X contended that the portion of the assignment covering medical fee receivables with payment dates falling more than one year after the commencement of the assignment (i.e., after December 1983) was void. If this were true, then the fees generated during the disputed period (July 1989 - June 1990) rightfully belonged to A, not Y. Consequently, X's seizure of A's claim to the deposited funds (representing those fees) would be valid and take precedence over Y's claim based on the (allegedly partially invalid) assignment.

Lower Court Rulings: Both the court of first instance and the High Court agreed with X's position and ruled in favor of the State. Their reasoning hinged on the interpretation of the validity of assigning future receivables:

- They held that assignments of future medical fee claims are valid only if they pertain to the "not-so-distant future" where the stable generation of claims exceeding a certain amount can be "reliably expected" (確実に期待される - kakujitsu ni kitai sareru).

- They reasoned that medical fee receivables are typically a doctor's primary source of income. Assigning these receivables far into the future could severely constrain the doctor's business operations and potentially lead to financial hardship.

- They inferred that a doctor resorting to such a long-term assignment, especially when a creditor demands it, likely indicates that the doctor's financial creditworthiness was already significantly impaired at the time of the contract.

- Applying this logic, they found that the claims arising during the disputed period (over six and a half years after the assignment began) could not have been "reliably expected" to arise with certainty back in 1982 when the contract was signed.

- Therefore, they concluded that the portion of the assignment agreement covering this later period, including the specific claims seized by X, was invalid. This meant A was the rightful owner of the claims, and X's seizure of A's right to the deposited funds was effective. Y appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Analysis: A New Framework for Future Claim Assignments

The Supreme Court, in its judgment dated January 29, 1999, fundamentally disagreed with the lower courts' approach and overturned their decisions. The Court established a clearer and more permissive framework for evaluating the validity of assignments of future claims.

1. Specificity Requirement:

The Court first affirmed a basic principle: for any claim assignment (present or future) to be valid, the subject matter – the claim(s) being assigned – must be sufficiently identified. This includes identifying the cause of the claim's generation and the amount involved. When assigning multiple claims expected to arise or become payable within a future period, the contract must adequately specify this period (e.g., by defining clear start and end dates) to identify the scope of the assigned claims. The Court found that the agreement between A and Y met this specificity requirement, clearly defining the period and the monthly amounts assigned.

2. Rejection of the "Probability/Certainty" Test:

The Supreme Court explicitly rejected the lower courts' core rationale that the validity of assigning future claims depends on the high probability or certainty of those claims actually arising, or that assignments are only valid for the "not-so-distant" future. The Court stated:

- Parties entering into an assignment of future claims typically consider the circumstances underlying the potential generation of those claims and assess the likelihood of them arising.

- They understand that the claims might not materialize as expected. The risk associated with this non-materialization is generally addressed through the assignor's contractual liability (i.e., the assignee can pursue remedies against the assignor if the promised future claims fail to appear).

- Therefore, the mere fact that the probability of the claims arising was low at the time the contract was signed does not, in itself, automatically affect the validity of the assignment contract.

This marked a significant departure from the interpretation prevalent in lower courts and some legal commentary, which had focused heavily on the predictability and temporal proximity of future claims.

3. The Public Policy Limitation:

While rejecting the probability test, the Court introduced a crucial limitation based on public policy (公序良俗 - kōjo ryōzoku, public order and morals – akin to public policy in common law). The Court held that an assignment of future claims, even if sufficiently specific, can be deemed wholly or partially void if it violates public policy.

Whether an assignment violates public policy requires a comprehensive assessment of various factors, including:

- The assignor's financial condition at the time of the contract.

- The assignor's business prospects and operational outlook at that time.

- The specific content of the assignment agreement (e.g., the duration, the proportion of income assigned).

- The circumstances surrounding the conclusion of the contract.

An assignment might be found void against public policy under "special circumstances" (特段の事情 - tokudan no jijō), such as when:

- The contract terms (like the duration) impose restrictions on the assignor's business activities that markedly deviate from socially accepted norms or standards.

- The assignment causes undue disadvantage to the assignor's other creditors.

4. Application to the Facts of the Case:

Applying this framework, the Supreme Court found no "special circumstances" warranting the invalidation of the assignment between A and Y on public policy grounds.

- The Court acknowledged that physicians often incur substantial debt when establishing clinics or purchasing medical equipment, and may lack traditional collateral like real estate.

- It recognized the commercial reasonableness of using future medical fee receivables as security for loans in such situations. Lenders might rationally provide financing based on the prospect of future earnings generated by the funded facilities, even without existing tangible collateral. For the borrowing doctor, assigning a defined portion of future receivables based on projected income can be a reasonable way to manage debt repayment.

- The Court emphasized the social utility of this financing method, as it enables financial support for capable individuals who may lack current assets but have strong future prospects.

- Critically, the Court stated that the mere act of a doctor entering into such a long-term assignment does not automatically imply that the doctor's financial condition was already poor at the time, nor does it inevitably lead to future financial deterioration.

- In this specific case, there was no evidence presented to suggest that A was in dire financial straits when the contract was made, or that the terms of the assignment (despite its long duration) unduly restricted A's practice or unfairly prejudiced other potential creditors. The assignment specified fixed monthly amounts, not A's entire income stream.

- Since no special circumstances indicating a public policy violation were proven, the assignment, including the portion covering the period disputed by X, was deemed valid.

5. Clarifying Precedent:

The Supreme Court also addressed a widely cited 1978 Supreme Court decision that had been interpreted by many (including the lower courts in this case) as setting a general rule limiting the validity of future medical fee assignments to approximately one year. The 1999 Court clarified that the 1978 ruling was specific to the facts of that particular case and should not be understood as establishing a general standard or time limit for the validity of future claim assignments based on probability or temporal proximity.

Judgment and Implications

Based on this analysis, the Supreme Court concluded that the lower courts had erred in interpreting and applying the law by invalidating the assignment based on the low probability of claim generation so far in the future. This error clearly affected the outcome. The Court therefore:

- Reversed the High Court's judgment.

- Cancelled the first instance court's judgment (which had also favored X).

- Dismissed the claim brought by X (the State).

- Ordered X to bear all court costs.

This judgment has had profound implications for commercial law and financing practices in Japan:

- Validation of Future Claim Assignments: It provided strong judicial backing for the general validity of assigning future receivables, moving away from restrictive tests based on probability or duration. This brought Japanese law more in line with practices supporting modern financing techniques like asset-based lending and factoring, where future income streams are crucial collateral.

- Focus on Specificity and Public Policy: The decision established a clearer two-pronged test: the assignment must be specific enough to identify the claims, and it must not violate public policy. The public policy check acts as a safeguard against abusive or overly burdensome assignments, considering factors like the assignor's freedom of business and fairness to other creditors.

- Enhanced Predictability for Secured Lending: By rejecting the unpredictable "probability" test and clarifying that long durations are not inherently invalid, the ruling enhanced legal certainty for lenders relying on future receivables as collateral.

- Interplay with Perfection: While the case focused on validity, it operated against the background of perfection. Y had perfected its assignment against third parties by notifying the Fund with a certified date, a requirement under the Civil Code at the time. Subsequent legal reforms introduced specific registration systems for assignments of claims, providing alternative methods for perfection, but the validity principles established in this case remain central.

- Distinction from Seizure Rules: While this ruling liberalized the assignment of future claims, it's worth noting that the legal framework and historical practice surrounding the seizure (attachment) of future claims by judgment creditors or tax authorities have followed a partially distinct path. Practices involving duration limits for seizure (such as a commonly cited one-year limit) existed historically. Later amendments to the Civil Execution Act specifically addressed the seizure of future 'claims related to continuous performance,' potentially aligning the rules for seizure more closely with the liberal approach to assignment validated here, especially concerning regular income streams like medical fees.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's January 29, 1999 decision represents a pivotal moment in Japanese jurisprudence regarding the assignment of future claims. By rejecting a restrictive approach based on the probability of claim generation and temporal proximity, the Court embraced a more commercially practical standard centered on specificity and limited only by fundamental principles of public policy. This ruling confirmed the general validity of using future receivables, including long-term streams like medical fees, as collateral, thereby facilitating modern financing methods while retaining a mechanism to prevent genuinely abusive arrangements. It remains a cornerstone decision for understanding secured transactions involving future assets in Japan.