Assigned Claims with "No-Assignment" Clauses: A Look at Pre-2017 Japanese Law and Third-Party Rights

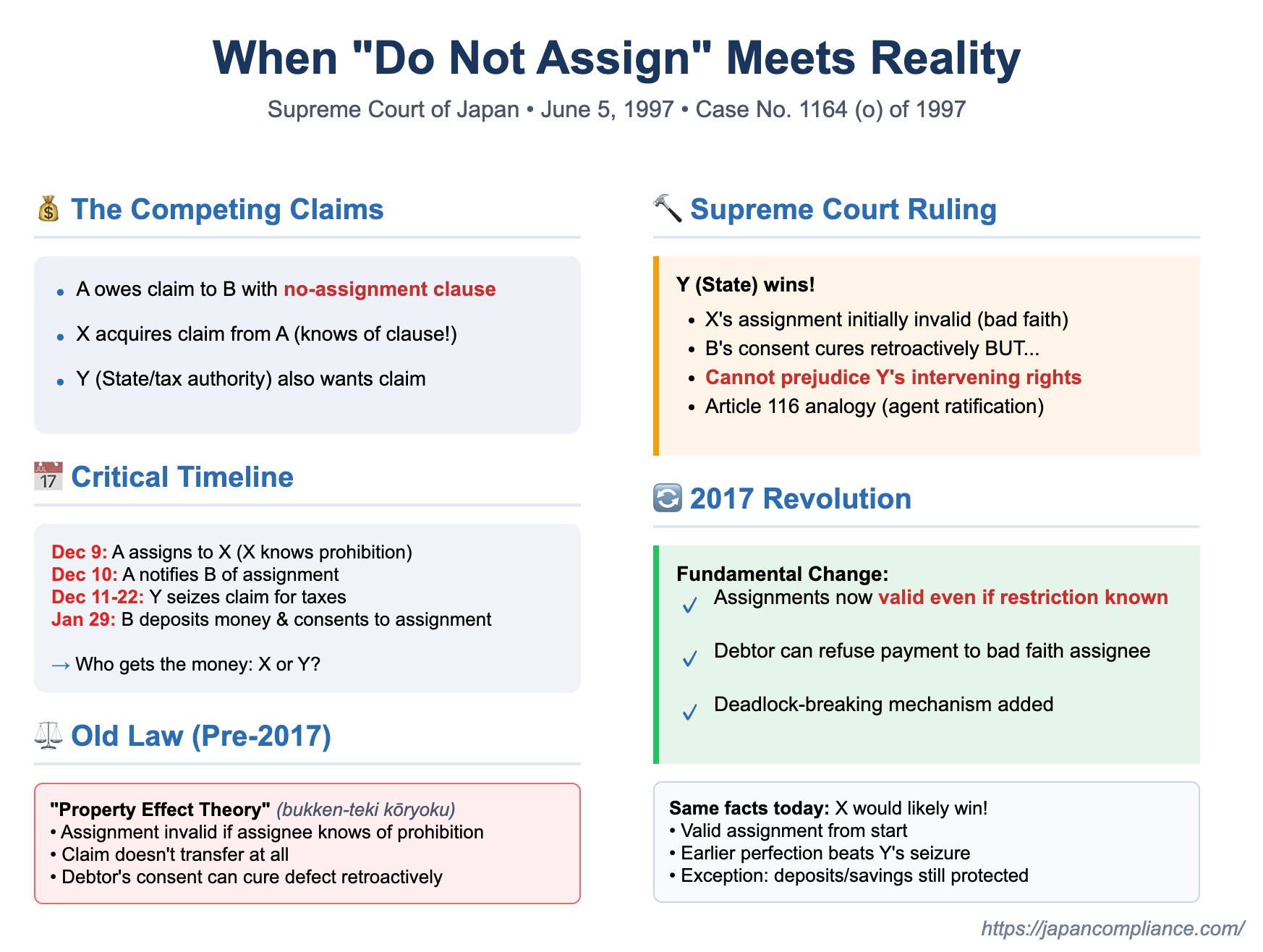

The ability to assign (sell or transfer) contractual rights, particularly monetary claims like accounts receivable, is a cornerstone of modern commerce, facilitating financing and liquidity. However, contracts often include clauses that restrict or outright prohibit the assignment of claims arising under them. A Japanese Supreme Court decision from June 5, 1997 (Heisei 5 (O) No. 1164), delved into the complex legal battles that could arise when such a "no-assignment" clause was breached, especially when the assignee was aware of the clause, and other creditors also laid claim to the same asset. This case provides a valuable window into the legal landscape in Japan before the significant Civil Code reforms of 2017.

Assignment Prohibition Clauses: The Old Legal Landscape (Pre-2017 Reforms)

Under the Japanese Civil Code prior to the 2017 amendments (specifically, former Article 466):

- General Assignability: As a general rule, contractual claims were freely assignable.

- Assignment Prohibition by Agreement: However, parties to a contract could agree to prohibit the assignment of claims arising from that contract. This was known as a "no-assignment clause" or "assignment prohibition clause" (jōto kinshi tokuyaku).

- Protection of Good Faith Assignees: Such a prohibition could not be asserted by the debtor against a third-party assignee who acquired the claim in "good faith." Case law had established that "good faith" in this context meant the assignee was unaware of the prohibition and was not grossly negligent in failing to discover it. Simple negligence on the assignee's part generally did not prevent them from validly acquiring the claim.

- The "Property Effect" Theory: The prevailing legal theory and judicial stance at the time (often called the "property effect theory" or bukken-teki kōryoku setsu) was that if an assignment violated a no-assignment clause, and the assignee was not in good faith (i.e., they knew of the prohibition or were grossly negligent), the assignment itself was considered invalid. The claim simply did not transfer to the assignee; it wasn't merely a case of the assignor breaching the contract with the debtor.

Facts of the 1997 Case: A Prohibited Assignment, an Aware Assignee, and Competing Creditors

The 1997 case involved a typical scenario testing these rules:

- The Parties:

- A: The original creditor who held an accounts receivable claim (the "Claim") against B.

- B: The debtor who owed the Claim to A. The contract between A and B contained a no-assignment clause.

- X: The assignee who received the Claim from A, typically as a form of payment (substitute performance - daibutsu bensai) for a separate debt A owed to X.

- Y: An intervening creditor (in this case, the State acting as the tax authority) who also had claims against A and sought to seize the Claim.

- The Disputed Assignment: On December 9, 1987, X acquired the Claim from A. Crucially, X either knew about the no-assignment clause or was grossly negligent in not knowing about it. A notified B (the debtor) of this assignment on December 10, 1987.

- Intervening Seizure: After B was notified of the assignment to X, but before B formally consented to it, Y (the State) took action to seize the Claim from A on December 11 and 22, 1987, due to A's unpaid taxes. Notices of this tax seizure were served on B. Other creditors also initiated attachment proceedings around this time.

- Debtor's Consent and Deposit: On January 29, 1988, B, faced with competing claims and uncertainty about whom to pay, deposited the amount of the Claim with the authorities. Importantly, at the time of making this deposit, B formally consented to the original assignment of the Claim from A to X.

- The Legal Battle: X and Y then disputed who had priority and the right to the deposited funds. The lower appellate court had ruled in favor of Y (the tax authority), holding that while B's consent made the assignment to X retroactively valid, its opposability against third parties like Y only started from the time of consent, by which point Y's seizure was already in place.

The Supreme Court's Ruling: Consent Cures, But Third-Party Rights are Protected

The Supreme Court dismissed X's appeal, affirming the priority of Y's tax seizure. Its reasoning was a careful balancing act:

- Assignment Initially Ineffective against Bad Faith/Grossly Negligent Assignee: The Court confirmed that because X knew (or was grossly negligent in not knowing) about the no-assignment clause, X did not immediately and validly acquire the Claim at the moment of the assignment agreement with A. This aligned with the "property effect theory."

- Debtor's Consent Creates Retroactive Validity: However, the Court held that when the debtor (B) subsequently consented to the assignment, this consent had the effect of making the originally problematic assignment from A to X valid. Furthermore, this validity was retroactive to the time of the original assignment agreement between A and X.

- Crucial Limitation – Protection of Intervening Third-Party Rights (Analogy to Civil Code Article 116): This is where the decision became particularly nuanced. While the assignment became retroactively valid as between A, B, and X, the Court stated that this retroactive effect could not prejudice the rights of third parties who had acquired an interest in the claim before the debtor's consent was given. To support this, the Court invoked the "spirit of Article 116" of the Civil Code. Article 116 deals with the ratification of an act performed by an unauthorized agent; ratification is retroactive but explicitly states it cannot impair the rights of third parties acquired in the interim.

- Outcome in the Case: Since Y (the State) had validly seized the Claim from A before B consented to the assignment to X, Y's rights took priority. X could not assert the retroactively validated assignment against Y to defeat Y's pre-existing seizure.

Unpacking the Reasoning (Pre-2017 Legal Context)

This 1997 judgment is a key illustration of how Japanese courts navigated the complexities of no-assignment clauses under the old Civil Code.

- The "Curing" Effect of Debtor's Consent: The idea that a debtor's subsequent consent could "cure" an initially invalid assignment (due to a known prohibition) and make it retroactively effective was a significant feature of pre-2017 case law. This judgment solidified the analogy to Article 116 (ratification of an unauthorized agent's act) as the theoretical underpinning for this retroactive validation.

- The Priority Puzzle: The critical question was how this retroactive validation interacted with the rights of third parties, like Y, who had acted in the period between the (initially ineffective) assignment to X and B's later consent. The Supreme Court resolved this by prioritizing the rights of the intervening third party over the full retroactive effect of the consent, at least as far as the bad-faith/grossly negligent assignee was concerned. The Court reasoned that the consent makes the assignment's validity itself retroactive, but this retroactivity is limited when it comes to harming established third-party rights.

The Fundamental Shift: How the 2017 Civil Code Reforms Changed the Rules

The legal landscape for assignments with restrictions changed dramatically with the 2017 Civil Code reforms. The old "property effect theory" was largely abandoned as the default.

- Assignments Violating Restrictions Now Generally Valid (New Article 466): Under the reformed Article 466, an assignment of a claim made in violation of an "assignment restriction clause" (jōto seigen tokuyaku – a broader term than the old "prohibition") is, in principle, valid and effective from the outset.

- Debtor's Defenses Against Certain Assignees: The primary effect of the restriction clause now lies in the defenses it gives to the debtor. If the assignee knew of the restriction or was grossly negligent in not knowing (the same standard as before), the debtor can:

- Refuse to pay the assignee.

- Validly discharge the debt by paying the original assignor.

This can lead to a "deadlock" if the debtor refuses the assignee but also doesn't pay the assignor. The new law provides a mechanism (new Article 466, Paragraph 4) for the assignee to break this deadlock by demanding the debtor pay the assignor within a reasonable time, failing which the debtor must pay the assignee.

- Likely Different Outcome for X vs. Y Today: If the facts of the 1997 case were adjudicated under the current (post-2017) law for a typical accounts receivable:

- The assignment from A to X would likely be considered valid from the beginning, despite X's knowledge of the restriction.

- X perfected this valid assignment by ensuring A notified B on December 10.

- Y's tax seizure occurred on December 11 and 22.

- Thus, X, having a valid and earlier-perfected assignment, would likely have priority over Y's subsequent seizure.

- B's later consent would be less critical for determining priority between X and Y. B could still potentially refuse to pay X directly (due to X's knowledge of the restriction), but this would be a matter between X and B, likely resolved through the deadlock-breaking provisions.

- Special Exception for Deposits/Savings Claims: It's important to note that the reformed Civil Code (new Article 466-5) carves out an exception for deposit and savings account claims. For these types of claims, if they are assigned in violation of a restriction, the restriction can be asserted against a bad faith or grossly negligent assignee, effectively making the assignment invalid against the financial institution (similar to the old "property effect"). This exception acknowledges the unique operational needs of banks handling a high volume of such claims.

Conclusion: A Window into Past Law, A Benchmark for Legal Evolution

The 1997 Supreme Court judgment in this case offers a fascinating glimpse into how Japanese law, prior to the 2017 reforms, sought to balance the interests of debtors wishing to restrict the assignment of their obligations, assignees (even those aware of such restrictions), and other creditors vying for the same asset. The Court's use of an analogy to Article 116 (ratification of an unauthorized agent's act) to explain the retroactive effect of a debtor's consent, while simultaneously protecting intervening third-party rights, was a key piece of judicial reasoning.

While the specific rules governing the validity and effect of assignments violating restriction clauses have been fundamentally revised by the 2017 Civil Code—generally moving towards upholding the validity of such assignments by default—this 1997 case remains an important historical landmark. It illustrates the challenges posed by such clauses and serves as a benchmark for understanding the significant evolution of Japanese commercial and contract law.