Art, Erotica, and the Law: The Landmark Japanese "Lady Chatterley's Lover" Trial

Decision Date: March 13, 1957

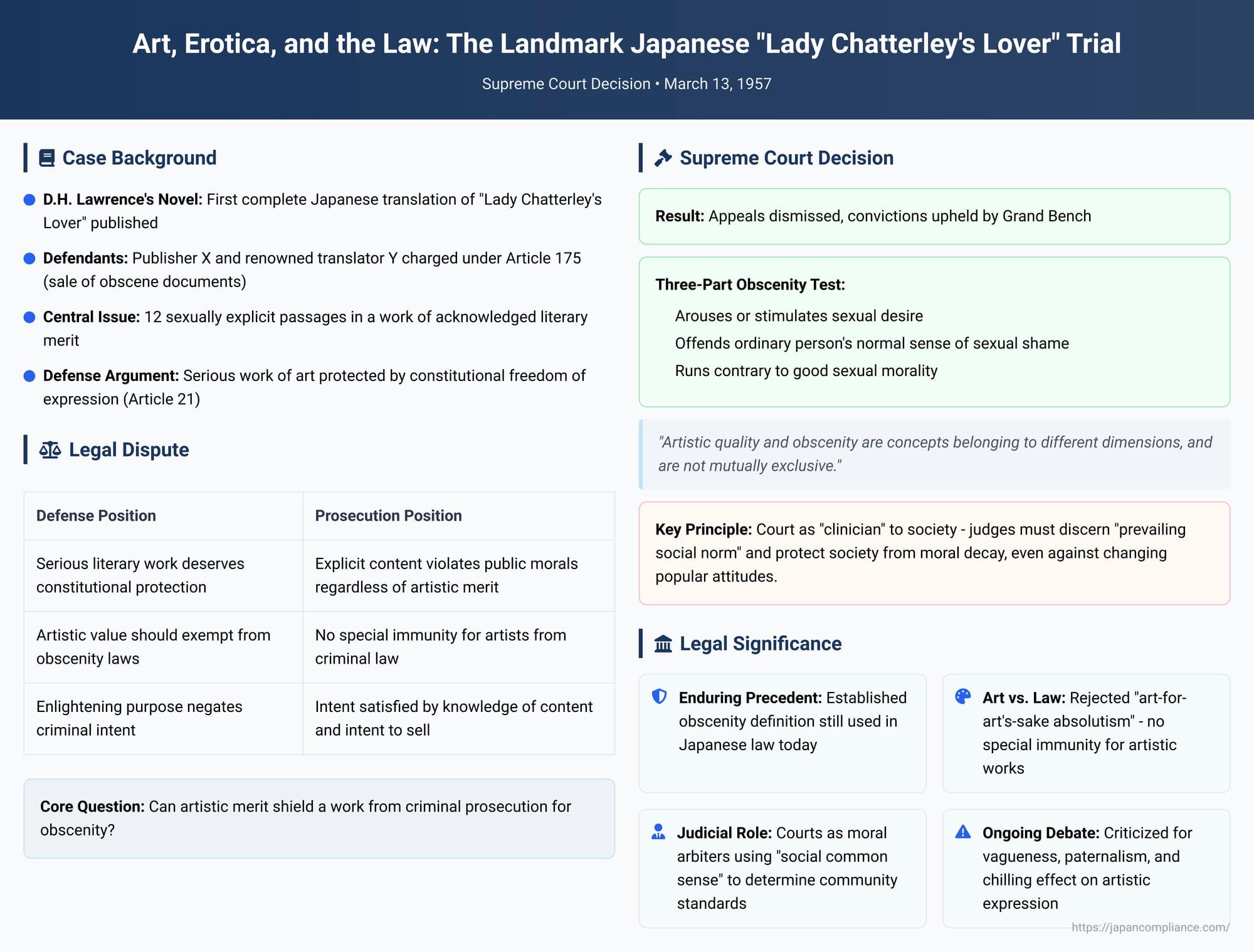

Where does art end and obscenity begin? Who has the right to draw that line, and by what standard? This timeless conflict between freedom of expression and the protection of public morals has been fought in courtrooms around the world, but few legal battles have been as consequential or as philosophically revealing as Japan's trial over D.H. Lawrence's novel, Lady Chatterley's Lover. The case, which culminated in a landmark Supreme Court decision on March 13, 1957, did more than just decide the fate of a single book. It established the enduring legal definition of obscenity in Japan and saw the nation's highest court assert its role as the ultimate arbiter of social norms, famously declaring that even a work of high art is not immune from the judgment of the law.

The Factual Background: A Controversial Masterpiece in Japan

The case centered on the first complete Japanese translation of D.H. Lawrence's final novel, Lady Chatterley's Lover. The defendants were the publisher of the book, X, and the translator, Y, a renowned literary figure in his own right. The book itself was, and remains, a work of significant literary merit, praised for its rich character development, its cutting critique of industrialization and class society, and its profound, if controversial, life philosophy. The novel's central theme is the pursuit of human fulfillment through the complete satisfaction of sexual desire, a philosophy that directly challenged the traditional, puritanical sexual mores of the time.

It was this philosophical core, expressed through a number of sexually explicit passages, that led to the book's prosecution. After the translated novel was published and sold, both the publisher X and the translator Y were charged with the sale of obscene documents, a crime under Article 175 of the Penal Code.

The Journey Through the Courts: Art vs. Law

The case immediately became a national sensation, pitting the literary world against the legal establishment. The defendants' core argument was that Lady Chatterley's Lover was a serious work of art and thought, not pornography, and that its prosecution was an unconstitutional infringement on the freedom of expression guaranteed by Article 21 of the Japanese Constitution.

The lower courts wrestled with this conflict. The trial court convicted the publisher X but, finding his role to be more peripheral, acquitted the translator Y. The Tokyo High Court, however, convicted both men, setting the stage for a final showdown in the Supreme Court. The defendants appealed, arguing that the book's artistic value and serious intent placed it outside the scope of obscenity law.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Decision

The Supreme Court, sitting as a Grand Bench, dismissed the appeals and upheld the convictions in a sweeping and deeply philosophical opinion that would shape Japanese law for decades to come.

1. Defining "Obscenity"

First, the Court laid out its definitive three-part test for determining what constitutes an obscene document under Article 175. Drawing on its own precedents and those of the pre-war Daishin-in, the Court held that a work is legally obscene if it:

- Arouses or stimulates sexual desire;

- Offends the ordinary person's normal sense of sexual shame; and

- Runs contrary to good sexual morality.

2. The Court as the Arbiter of Social Norms

The Court then made a powerful assertion about its own judicial role. It declared that the determination of whether a work is obscene is not a question of fact to be proven with evidence, but a question of legal interpretation for the court to decide. The standard for this judgment, the Court stated, is the "prevailing social norm" or "social common sense" (shakai tsūnen). This norm, it explained, is not a simple "aggregate or average of individual perceptions" but rather a "collective consciousness" that the judge, using their own good sense, is tasked with discerning.

3. Art and Obscenity Can Coexist

This was the most famous and consequential part of the ruling. The Court directly confronted the argument that a work's artistic value should shield it from obscenity laws. It rejected this idea completely, stating:

"Artistic quality and obscenity are concepts belonging to different dimensions, and are not mutually exclusive."

A work can be both a literary masterpiece and legally obscene. The Court dismissed what it called "art-for-art's-sake absolutism," declaring that art does not possess any special privilege to provide the public with obscene materials. Artists, like all citizens, are bound by the law and have a duty to respect the "minimum morality" required to maintain social order.

4. Applying the Standard to Lady Chatterley's Lover

The Court then applied its test to the book itself. It focused on the twelve explicit sexual passages identified by the prosecution, describing them as "exceedingly bold, detailed, and realistic". The Court found that these passages violated what it termed the "principle of the privacy of the sexual act," a norm it viewed as fundamental to human dignity. The descriptions were of a degree that would "offend the sense of shame" and would be embarrassing to read aloud in a family or public setting. Therefore, the Court concluded, the depictions "exceeded the limits tolerated by the prevailing social norm" and the book was, as a matter of law, an obscene document.

5. The Question of Criminal Intent

Finally, the Court dismissed the defendants' argument that their literary and "enlightening" motives negated their criminal intent. It ruled that for the crime of selling an obscene document, intent is satisfied if two things are recognized by the defendant: (1) the existence of the explicit content in the work, and (2) the intent to sell the work containing it. A defendant's personal belief that the work is not legally obscene is merely an error of law, which cannot negate criminal intent.

A Deeper Dive: The Philosophy and Critique of the "Chatterley" Ruling

The 1957 decision is remarkable for its deep engagement with social and legal philosophy. It is not merely a technical application of a statute but a broad statement on the role of law in society.

The "Minimum Morality" of Law:

The Court's reasoning is built on a specific conception of law's purpose. It acknowledges that law is not tasked with enforcing all morality; that is the domain of education and religion. However, the law is responsible for maintaining the "minimum morality" that is essential for social order. The Court placed the prohibition on obscenity firmly within this "minimum morality," arguing that it protects the public from a "danger" that could "paralyze the human conscience regarding sex, disregard the limits of reason, and induce licentious and unrestricted behavior, ignoring sexual morality and order."

The Court as "Clinician":

In one of its most controversial passages, the Court defended its role as a moral arbiter against the charge that it was ignoring changing social norms. It stated that even if "the ethical sense of a considerable number of the populace has become paralyzed, and they no longer recognize as obscene that which is truly obscene," the court must follow the norms of "sound and healthy people" and "protect society from moral decay." The Court declared:

"[L]aw and the courts do not necessarily always affirm social reality, but must, with a critical attitude, confront sickness and decay and play the role of a clinician."

This view casts the judiciary as a paternalistic guardian of public morals, with a duty to act as a "doctor" to a "sick" society.

Enduring Critiques:

The ruling, while influential, has been the subject of decades of criticism from legal scholars and free-speech advocates.

- Vagueness and Subjectivity: The three-part test for obscenity, which relies on subjective concepts like the "normal sense of sexual shame" and "good sexual morality," has been criticized as being too vague and leaving too much to the personal discretion of individual judges.

- Paternalism: The "court as clinician" metaphor is seen by many as profoundly paternalistic and anti-democratic, positioning the judiciary as a moral authority superior to the evolving standards of the public.

- Chilling Effect on Art: The core principle that high artistic merit cannot save a work from being declared obscene has been a constant source of friction. Critics argue that this forces artists who deal with themes of sexuality to self-censor, fearing that their work, no matter how serious or artistically rendered, could fall foul of a court's subjective moral judgment.

Conclusion: A Lasting and Controversial Precedent

The Lady Chatterley's Lover trial was a watershed moment in Japanese history. The Supreme Court's 1957 decision established the definitive legal framework for obscenity that remains in place to this day. It enshrined the principle that artistic expression, though a constitutionally protected freedom, is not absolute and must yield to the "public welfare" as defined by the courts in their role as guardians of public morality.

By holding that art and obscenity can coexist in the same work, the Court drew a line that has shaped and, many would argue, constrained artistic expression in Japan for over half a century. While praised by some for its robust defense of social order, the ruling remains highly controversial, a powerful symbol of the enduring and unresolved tension between the freedom of the artist and the moral authority of the law.