Appeal Rights and Juvenile Compensation in Japan: The 2001 Supreme Court Decision

Decision Date: December 7, 2001

Introduction

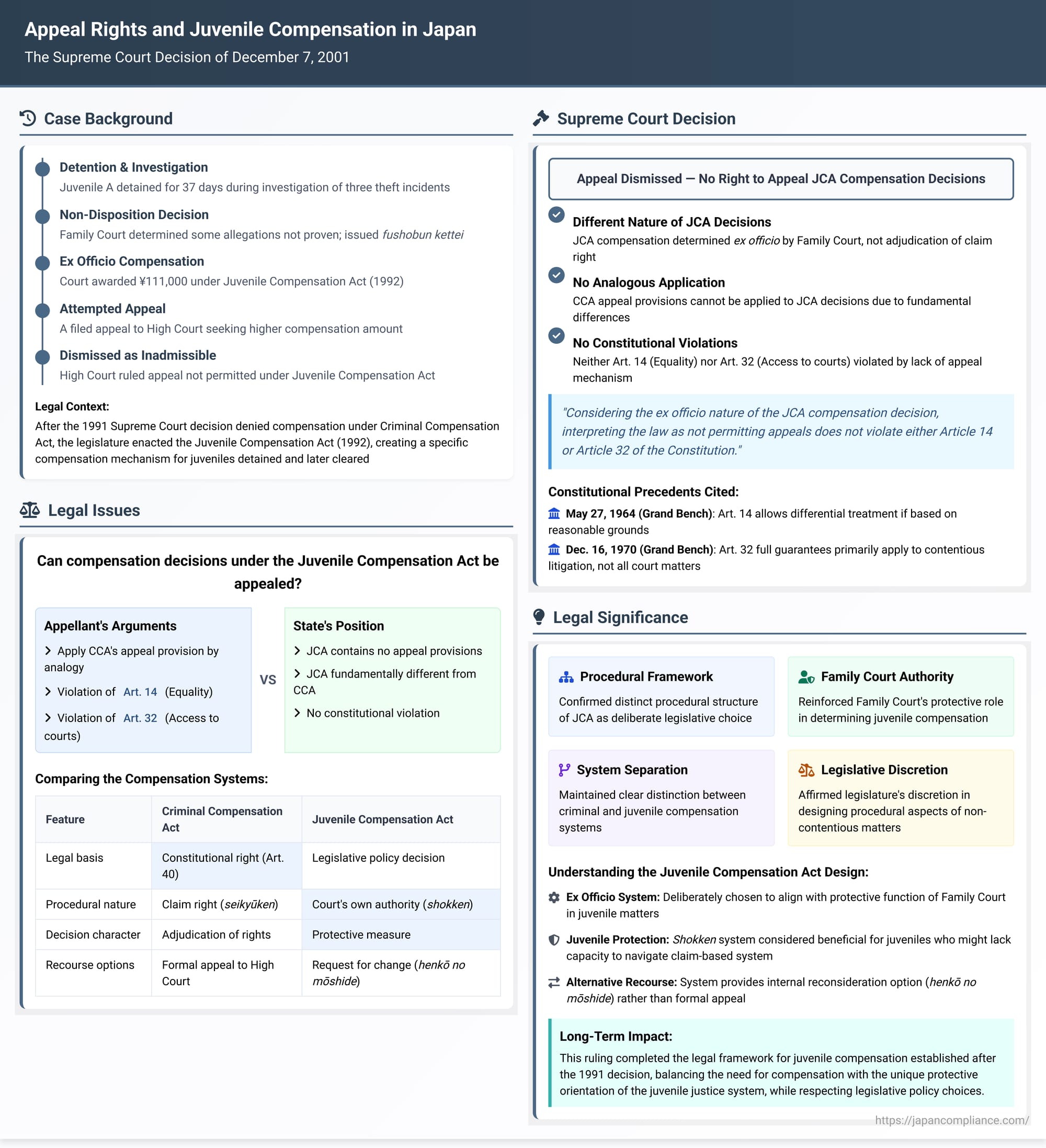

Following the enactment of Japan's Act Concerning Compensation Pertaining to Juvenile Protective Cases in 1992 (hereinafter "Juvenile Compensation Act" or JCA), questions arose regarding the procedural rights associated with this new system. Unlike the established Criminal Compensation Act (CCA), the JCA did not explicitly provide a mechanism for appealing the compensation decisions made by Family Courts. This led to a crucial legal challenge addressed by the Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench, in a decision dated December 7, 2001. The case examined whether a juvenile dissatisfied with the amount of compensation awarded under the JCA could appeal that decision, potentially by applying the appeal provisions of the CCA by analogy, and whether denying such an appeal violated constitutional guarantees.

Factual Background

The appellant, a minor anonymized as A, was referred to the Family Court for three alleged theft incidents. During the juvenile hearing (shinpan), the court determined that the facts constituting delinquency (hikō jijitsu) could not be established for some of the alleged incidents. Consequently, A received a non-disposition decision (fushobun kettei) regarding those specific allegations.

Prior to this outcome, A had been detained for a total of 37 days, likely including time spent under an "observation measure" (kango sochi) in a Juvenile Classification Home. Recognizing this period of detention preceding the partial clearing of allegations, the Family Court initiated compensation proceedings under the Juvenile Compensation Act. Acting on its own authority (shokken), as stipulated by the JCA, the court decided to award A compensation amounting to ¥111,000 (approximately $925 USD at late 2001 exchange rates).

The Claim and Lower Court Proceedings

Dissatisfied with the amount awarded, believing it to be too low, A filed an appeal (kōkoku) with the High Court. The central legal argument was necessarily creative, given the JCA's structure. While Article 5, Paragraph 3 of the JCA allows a juvenile (or their representative) to make a "request for change" (henkō no mōshide), essentially asking the Family Court to reconsider its own decision, the Act contains no provision for appealing the initial compensation decision (made under Article 5, Paragraph 1) to a higher court.

Therefore, A argued that the appeal mechanism found in the Criminal Compensation Act should be applied. Specifically, Article 19, Paragraph 1 of the CCA allows for an immediate appeal (sokuji kōkoku) against decisions concerning criminal compensation. A contended that the spirit (shushi) of this provision should be applied mutatis mutandis (with necessary changes) or by analogy (jun'yō nai shi ruisui tekiyō) to decisions made under the JCA.

Furthermore, A raised constitutional objections, arguing that if such an appeal were not permitted:

- It would violate Article 14 of the Constitution (guaranteeing equality under the law), presumably by treating juveniles differently from adults who can appeal decisions under the CCA.

- It would violate Article 32 of the Constitution (guaranteeing the right of access to the courts), by denying a pathway to higher judicial review for a decision affecting the juvenile's interests.

The High Court, however, dismissed A's appeal as inadmissible (futekihō). Its reasoning was direct:

- The JCA simply does not provide any avenue for appealing compensation decisions via ordinary appellate procedures.

- Juvenile compensation under the JCA is fundamentally different in nature from criminal compensation under the CCA, which is guaranteed as a claim right stemming from Article 40 of the Constitution. Therefore, there is no room under current law to apply the CCA's appeal provisions mutatis mutandis or by analogy.

- The absence of an appeal mechanism against Family Court decisions on juvenile compensation does not violate the right of access to courts under Article 32.

Undeterred, A filed a special appeal (tokubetsu kōkoku) to the Supreme Court, reiterating the arguments regarding the analogous application of the CCA's appeal provisions and the alleged violations of Articles 14 and 32 of the Constitution.

The Supreme Court's Decision and Rationale

The Supreme Court, Second Petty Bench, unanimously dismissed A's special appeal, affirming the High Court's judgment. The core of the Supreme Court's reasoning focused on the distinct nature of decisions made under the Juvenile Compensation Act compared to those under the Criminal Compensation Act.

1. Nature of the Juvenile Compensation Decision:

The Court emphasized that a compensation decision under Article 5, Paragraph 1 of the JCA is one where the Family Court, acting ex officio (shokken), determines the necessity and the content (amount) of the compensation. This is a determination made based on the court's own initiative and judgment within the framework of the juvenile justice system's protective goals.

This fundamentally differs from a decision under the Criminal Compensation Act. The CCA deals with adjudicating a claim right that arises for an individual who has been formally acquitted in criminal proceedings (a right rooted in Article 40 of the Constitution). The CCA process involves determining whether the conditions for this right are met and quantifying the compensation accordingly, often in a more adversarial context.

Because the nature (seishitsu) of the JCA decision is different from that of a CCA decision, the Court concluded that it is impermissible to apply the appeal provisions of the CCA (specifically Article 19, Paragraph 1) mutatis mutandis or by analogy. The High Court's conclusion on this point was deemed correct and justifiable (seitō).

2. Constitutional Arguments (Articles 14 and 32):

The Court then addressed the constitutional claims. It held that, considering the specific ex officio nature of the JCA compensation decision as described above, interpreting the law as not permitting appeals does not violate either Article 14 (Equality) or Article 32 (Right of access to courts).

To support this conclusion, the Court cited the spirit (shushi) of two key Grand Bench precedents:

- Supreme Court Grand Bench Decision, May 27, 1964 (Minshu Vol. 18, No. 4, p. 676): This case dealt with the constitutionality of laws concerning the partition of commonly owned property. It established the principle that Article 14's guarantee of equality is not absolute; differential treatment is permissible if based on reasonable grounds corresponding to the nature of the matter (jigara no seishitsu ni sokuō shite gōriteki to mitomerareru sabetsuteki toriatsukai). Applied here, the differing nature of JCA (ex officio, protective) and CCA (claim right, adversarial) compensation provides a reasonable basis for different procedural treatment (including appeal rights).

- Supreme Court Grand Bench Decision, December 16, 1970 (Minshu Vol. 24, No. 13, p. 2099): This case involved procedures for provisional disposition orders. It addressed the scope of Article 32 (right of access to courts). The precedent suggests that the full procedural guarantees associated with "trials" under the Constitution (like appeals to the highest court) primarily apply to purely contentious litigation (junzen taru soshō jiken) aimed at definitively determining rights and obligations between parties. It distinguished these from non-contentious matters (hishō jiken), which often involve court administration or determination of status/arrangements rather than resolving disputes over pre-existing rights. For non-contentious matters, the specifics of the procedure, including whether to allow appeals, are generally considered to be within the scope of legislative discretion (rippō sairyō) and not strictly mandated by Article 32.

The Supreme Court viewed the Family Court's ex officio determination of juvenile compensation under the JCA as falling closer to the category of a non-contentious matter. It is not about adjudicating a pre-existing claim right asserted by the juvenile against the state in an adversarial manner, but rather about the court, in its protective capacity, determining an appropriate measure based on its assessment of the situation. Therefore, the legislature's decision not to include a formal appeal mechanism in the JCA was deemed a permissible exercise of its discretion and not a violation of Article 32.

The Structure and Rationale of the Juvenile Compensation Act

Understanding the Supreme Court's 2001 decision requires appreciating why the Juvenile Compensation Act of 1992 was structured the way it was, particularly its departure from the claim-right and appeal structure of the Criminal Compensation Act. The PDF commentary associated with this case provides valuable insights into the legislative considerations:

- Legislative Policy vs. Constitutional Right: As highlighted in the previous 1991 Supreme Court decision (Heisei 1 (shi) No. 123), juvenile compensation under the JCA was conceived primarily as a matter of legislative policy and "distributive justice," rather than a direct implementation of the constitutionally guaranteed right to compensation upon acquittal (Article 40) that underpins the CCA. This foundational difference allowed for greater legislative flexibility in designing the JCA's procedures.

- Nature of Juvenile Fact-Finding: The determination of "no delinquency facts" (hikō jijitsu nashi) in a juvenile hearing, while significant, might not always result from the same rigorous, adversarial fact-finding process required for a formal acquittal in a criminal trial under the Code of Criminal Procedure. The juvenile system often prioritizes a more holistic assessment. This perceived difference made grounding compensation in a formal "claim right" (analogous to the CCA) seem less appropriate to the drafters.

- Family Court's Role and Expertise: The Japanese legal system places significant trust in the specialized expertise and protective orientation of the Family Court in juvenile matters. This is reflected elsewhere in the Juvenile Act (e.g., limitations on appellate courts overturning Family Court decisions directly, requiring remand instead in some cases). The JCA's structure, vesting the compensation decision in the Family Court's ex officio judgment, aligns with this principle, respecting the court's comprehensive understanding of the juvenile's situation gained through the hearing process. The decision made after investigation by the court or its probation officers (katei saibansho chōsakan) was seen as deserving deference.

- Protecting Vulnerable Juveniles: An ex officio system was considered more beneficial for juveniles, some of whom might lack the maturity, knowledge, or supportive environment needed to navigate a system based on asserting a formal claim right. Placing the responsibility on the court to initiate and determine compensation was seen as better aligned with the protective (kōkenteki kikan) role of the Family Court.

- Internal Reconsideration: While lacking a formal appeal, the JCA does provide Article 5, Paragraph 3, allowing the juvenile to request the Family Court to reconsider its own decision (henkō no mōshide). This internal mechanism was included as a safeguard, allowing for adjustments without resorting to a full appellate structure deemed inconsistent with the JCA's underlying philosophy.

These factors collectively explain why the JCA was deliberately designed without the appeal provisions found in the CCA. The Supreme Court's 2001 decision essentially validated this legislative design, confirming that the differences in procedure were constitutionally permissible given the distinct nature and purpose of juvenile compensation.

Post-2000 Amendment Considerations

The PDF commentary also touches upon the potential impact of the 2000 amendments to the Juvenile Act. These amendments introduced measures like prosecutor participation (kensatsukan kan'yo) and court-appointed attendants (kokusen tsukisoinin) in certain serious cases, and significantly, granted res judicata effect (barring re-prosecution) to non-disposition decisions in these specific, procedurally enhanced cases (Article 46, Paragraph 2). This addressed one of the key reasons cited in the 1991 decision for distinguishing juvenile non-disposition from criminal acquittal (i.e., lack of finality).

Some commentators argued that these changes made the "no delinquency" findings in such cases substantially equivalent to criminal acquittals. However, the prevailing view, reflected in the PDF commentary, seems to be that these amendments did not fundamentally alter the basic structure or protective orientation of the juvenile hearing process. Prosecutor and attendant participation is limited to certain cases, and their role is conceived as collaborators in the court's process, not full adversarial parties like in a criminal trial. Therefore, the commentary suggests that the rationale for the JCA's ex officio structure and the lack of appeals likely remained valid even after the 2000 amendments. The 2001 Supreme Court decision, coming after these amendments, appears consistent with this view, focusing on the inherent ex officio nature of the JCA decision itself, regardless of the procedural enhancements in specific underlying juvenile cases.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's December 7, 2001 decision clarified an important procedural aspect of Japan's juvenile compensation system. It firmly established that decisions made by Family Courts under the Juvenile Compensation Act regarding the necessity and amount of compensation are not appealable to higher courts. The Court's reasoning hinged on the fundamental difference between the JCA's ex officio mechanism, rooted in legislative policy and the protective role of the Family Court, and the Criminal Compensation Act's system based on a constitutionally derived claim right following a formal criminal acquittal. By categorizing the JCA decision as akin to a non-contentious matter where procedural details are subject to legislative discretion, the Court found no violation of the constitutional rights to equality (Article 14) or access to courts (Article 32) in the absence of an explicit appeal provision. This ruling underscores the distinct legal philosophy underpinning the Japanese juvenile justice system and validates the specific procedural choices made by the legislature when creating the Juvenile Compensation Act to address the gap identified in the earlier 1991 Supreme Court case. While providing a necessary compensation mechanism, the JCA was intentionally designed with procedures reflecting its unique basis and the specialized context of the Family Court.