Apparent Authority Risk in Japan: Lessons from a High Court Case on Assignment of Claims

TL;DR

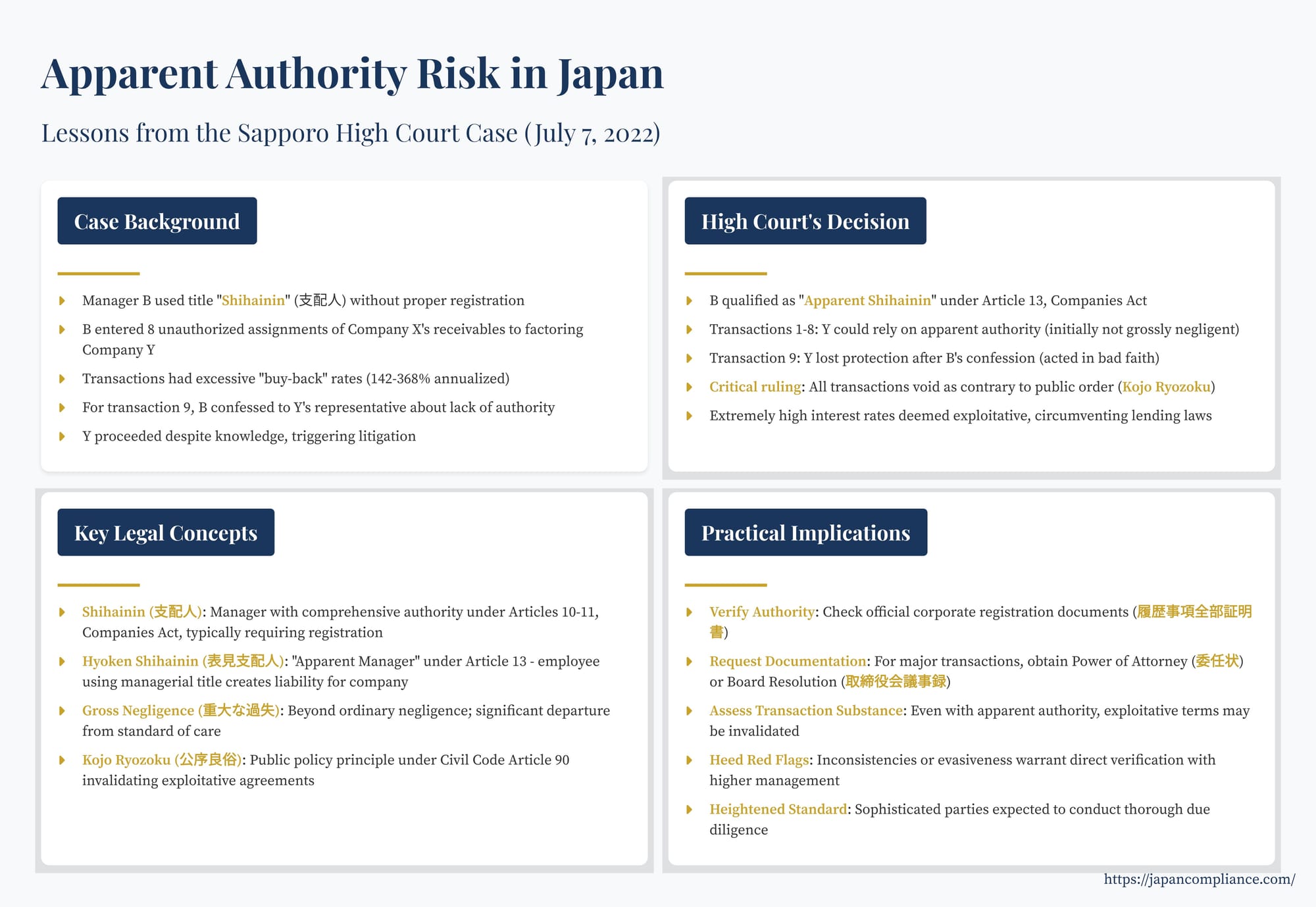

A July 7 2022 Sapporo High Court case shows that a company may still escape liability for contracts signed by an “apparent” manager if the terms are exploitative and violate public policy. The ruling clarifies when Article 13 Companies Act protects counterparties, how “gross negligence” is judged, and why courts can void deals under Civil Code Article 90 despite apparent authority.

Table of Contents

- The Sapporo High Court Case (July 7 2022)

- Key Japanese Legal Concepts

- Analysis and Further Considerations

- Practical Implications for US Companies

- Conclusion

When engaging in transactions with Japanese companies, understanding who has the legal authority to bind the company is paramount. While verifying the authority of registered representative directors is standard practice, situations involving managers or representatives whose authority isn't formally registered but appears broad can present significant risks. A July 7, 2022 decision by the Sapporo High Court highlights the potential pitfalls and protections offered by Japanese law concerning "apparent authority," while also demonstrating how egregiously unfair transactions can be invalidated on public policy grounds, even if apparent authority seemingly exists.

The Sapporo High Court Case (July 7, 2022)

Background

The case involved a company ("Company X"), a quasi-public entity majority-owned by a local municipality. Its representative director ("A"), the former deputy mayor, entrusted the company's day-to-day operations to a manager ("B") who used the title "Shihainin" (支配人). A shihainin is a legally defined type of manager under Japan's Companies Act with broad authority, typically requiring commercial registration. Although Company X had internal rules defining the scope of the shihainin's authority (limited to smaller transactions), B effectively controlled the company's finances, possessed the corporate seal, and managed bank accounts often without A's specific approval. Crucially, B was not formally registered as a shihainin.

Facing financial difficulties and concealing the company's precarious state (including through accounting fraud) from both A and the municipality, B sought funds from a factoring company ("Company Y"). From May 2018 to March 2019, B, representing Company X but without A's actual consent or knowledge, entered into a series of eight transactions with Company Y. These transactions were structured as assignments of Company X's receivables (claims against the city and prefecture for managed facility fees) to Company Y.

Company Y's representative ("C") was aware that B was not formally registered as a shihainin. However, B asserted comprehensive authority delegated by A. At C's request, B provided documents such as a power of attorney bearing Company X's representative seal and A's official seal certificate (presumably obtained by B without A's specific authorization for these transactions). The agreements involved assigning receivables, receiving funds from Y, and setting terms for X to "buy back" the receivables by a certain date. The difference between the funds advanced by Y and the buy-back amounts was exceptionally large, translating to annualized interest rates ranging from approximately 142% to 368%.

Initially, B managed to make the buy-back payments. However, B eventually could not fund the buy-backs for transactions 6, 7, and 8. Consequently, a ninth transaction was arranged where the funds advanced by Y were offset against the outstanding buy-back amounts. During the negotiations for this ninth transaction, B confessed to C that all prior dealings had been conducted without A's knowledge or approval. C reportedly responded, "I'll pretend I didn't hear that," and proceeded with the transaction. Subsequently, Company Y notified the underlying debtors (the city and prefecture) of the assignment for transaction 9. This brought the matter to A's attention in May 2019. The debtors deposited the payments related to transaction 9 with the Legal Affairs Bureau due to uncertainty about the rightful creditor.

Company X sued Company Y, arguing the assignments were invalid due to B's lack of authority and/or violation of public policy (kojo ryozoku - 公序良俗). X sought restitution of the net amounts paid to Y (buy-back amounts less funds received) and confirmation of its right to the deposited funds. The lower court partially ruled in favor of Company X. Company Y appealed.

The High Court's Decision

The Sapporo High Court upheld the lower court's finding in favor of Company X but expanded the reasoning.

- Lack of Actual Authority: The court affirmed that B lacked the actual authority to assign Company X's core revenue streams (the receivables). These were not routine transactions, and A had not granted B such comprehensive power. Furthermore, the lack of registration and the existence of internal rules limiting B's authority confirmed B was not a statutory Shihainin with inherent broad powers.

- Apparent Authority (Hyoken Shihainin - 表見支配人): Despite the lack of actual authority, the court found that B qualified as an "Apparent Shihainin" under Article 13 of the Companies Act. This was because B operated at Company X's head office using the title of shihainin. Article 13 states that a company is liable for acts performed by an employee who uses a title indicating authority over the business of the head office or a branch (like shihainin, branch manager, etc.), provided the counterparty acted in good faith (i.e., without knowledge of the actual lack of authority) and was not grossly negligent. An Apparent Shihainin is deemed to have authority over all judicial and non-judicial acts related to that business place.

- Counterparty's Status (Transactions 1-8): For the first eight transactions, the court determined that Company Y (through C) was neither aware of B's lack of authority nor grossly negligent in failing to discover it. Although C knew B wasn't registered as a shihainin, C relied on B's explicit representations of having delegated authority and the documents B provided (power of attorney, seal certificate). Therefore, Company Y was, in principle, protected by the doctrine of apparent authority for these initial transactions.

- Counterparty's Status (Transaction 9): However, for the ninth transaction, which occurred after B confessed to acting without A's approval, the court found Company Y (through C) was either acting in bad faith (knowing B lacked authority) or was grossly negligent. C's prior knowledge of the missing registration, coupled with B's confession and C's failure to conduct any further verification (like contacting A directly), precluded Company Y, a professional factoring entity, from relying on apparent authority for this final transaction.

- Violation of Public Policy (Kojo Ryozoku - 公序良俗): Crucially, the High Court went further and declared that transactions 1 through 8 were void as being contrary to public order and morality (Article 90 of the Civil Code). The court looked beyond the form of the transactions (claim assignments/factoring) to their substance, characterizing them as a means for Company Y to exploit Company X's dire financial situation and circumvent laws regulating lending (such as the Interest Rate Restriction Act and the Act Regulating the Receipt of Contributions, Receipt of Deposits and Interest Rates). The extremely high effective interest rates embedded in the "buy-back" structure were deemed usurious and exploitative.

Therefore, even though apparent authority might have protected Company Y for transactions 1-8 based solely on agency law principles, the fundamentally exploitative nature of the deals rendered them unenforceable under the broader principle of public policy. The High Court dismissed Company Y's appeal.

Key Japanese Legal Concepts

This case brings several important concepts in Japanese commercial law into focus:

- Shihainin (支配人): Defined in the Companies Act (Articles 10-11), a shihainin is a manager appointed by the company with comprehensive authority (judicial and non-judicial) over a specific place of business (head office or branch). Their appointment and authority must be commercially registered to be fully effective against third parties unaware of any internal limitations.

- Hyoken Shihainin (表見支配人 - Apparent Manager): Governed by Article 13 of the Companies Act, this doctrine protects third parties who reasonably rely on the appearance of authority created when an employee uses a title suggesting broad managerial power (like shihainin, branch manager - 支店長, etc.) at a company's place of business. The company is bound by the apparent manager's acts unless the third party knew the employee lacked actual authority or was grossly negligent in not knowing. This differs subtly from the common law concept of apparent authority, which often focuses more on the principal's manifestations creating the appearance of authority. Article 13 focuses on the use of specific titles at a place of business.

- Gross Negligence (重大な過失 - Judai na Kashitsu): To lose the protection of apparent authority under Article 13, a third party must have been more than merely negligent; they must have been grossly negligent. This implies a significant departure from the standard of care expected under the circumstances. In this case, simply knowing the shihainin registration was missing was not deemed gross negligence initially, given B's representations and document provision. However, proceeding after a direct confession of unauthorized dealing was considered grossly negligent for a professional factoring firm.

- Kojo Ryozoku (公序良俗 - Public Order and Morality): Article 90 of the Civil Code states that a juridical act whose object is contrary to public order or morality is void. This is a broad principle allowing courts to invalidate agreements that, while perhaps technically valid in form, are fundamentally unfair, exploitative, or violate underlying societal norms or mandatory laws. Examples include usurious contracts, agreements facilitating crime, or those unduly restricting personal freedom. The Sapporo High Court used this doctrine to strike down the factoring agreements due to their exploitative interest rates and the leveraging of the debtor's distress, even where apparent authority might otherwise have applied.

Analysis and Further Considerations

The Sapporo High Court's decision provides valuable lessons, but also leaves some nuances open, as legal commentary sometimes points out.

The Power of Public Policy: The most striking aspect is the invalidation of transactions 1-8 based on kojo ryozoku, despite the court finding that Company Y could have otherwise relied on apparent authority. This underscores that even seemingly valid transactions based on apparent authority can be overturned if their substance is deemed fundamentally exploitative or contrary to public policy. It serves as a reminder that the fairness and underlying legality of the transaction itself remain critical, independent of the agent's authority issues.

Apparent Authority vs. Internal Approvals: Legal analysis often considers whether a third party dealing with someone possessing apparent authority should still be mindful of internal company requirements, such as board resolutions (取締役会決議 - torishimariyaku-kai ketsugi) for significant transactions. Japanese company law (e.g., Article 362(4)) requires board approval for critical actions like disposing of important assets or large borrowings. The question arises: if a transaction is so significant that it would normally require board approval even if undertaken by the representative director, should a third party relying on the apparent authority of a manager be held to a standard of inquiring about such approvals? While the Sapporo court didn't explicitly delve into this, it highlights a potential grey area. Does the doctrine of apparent authority lower the counterparty's duty of care regarding the substance and internal authorization of the transaction itself? Prudence suggests that for major deals, confirming internal authorization remains advisable, regardless of the representative's apparent status.

Practical Implications for US Companies

This case offers several practical takeaways for US companies engaging with Japanese counterparts:

- Verify Authority Rigorously: Do not rely solely on titles like "Shihainin," "Branch Manager," or even "Director" without confirming actual authority for significant transactions. Request and review official corporate registration documents (履歴事項全部証明書 - rireki jiko zenbu shomeisho) listing registered representative directors. For specific major transactions, ask for a specific Power of Attorney (委任状 - ininjo) and/or a certified copy of the relevant Board Resolution (取締役会議事録 - torishimariyaku-kai gijiroku).

- Check Commercial Registration: Always check the commercial registry for the counterparty. Note the names of registered Representative Directors. If dealing with a shihainin, confirm their registration. Absence of registration for someone claiming broad authority is a red flag warranting further inquiry.

- Assess Transaction Substance: Be wary of transactions with unusually onerous terms, especially if the counterparty appears to be in financial distress. As the case shows, even if apparent authority exists, terms deemed exploitative or designed to circumvent regulations (like interest rate caps) can render the agreement void under the kojo ryozoku principle.

- Heed Red Flags: B's confession was a major red flag that shifted the court's view on Company Y's negligence. Similarly, inconsistencies, evasiveness about authority, inability to provide standard documentation, or pressure to conclude unusual deals quickly should trigger heightened scrutiny and verification, potentially by contacting higher-level management or legal departments directly.

- Understand the Scope of Apparent Authority: While Article 13 provides protection, it's not absolute. It depends on the third party acting without knowledge and without gross negligence. The standard of care may be higher for sophisticated parties or in non-routine transactions.

Conclusion

The Sapporo High Court decision serves as a potent reminder of the complexities surrounding agency and authority in Japanese corporate law. It affirms the doctrine of hyoken shihainin (apparent authority) but clarifies its limits, particularly concerning the counterparty's good faith and negligence. More significantly, it highlights the overriding principle of kojo ryozoku (public order and morality), demonstrating that courts can look through the form of a transaction to invalidate agreements deemed substantively exploitative or designed to circumvent law, even if entered into by someone with apparent authority. For US companies, the key lessons are the critical importance of thorough due diligence regarding both the counterparty representative's actual authority and the fundamental fairness and legality of the transaction itself.

- Perfecting Claim Assignments in Japan: Is the “Certified Date” or Actual Arrival Time Decisive for Priority?

- Director Liability in Japan: A Case Study Involving Attorney Directors and M&A

- Double Assignment of Claims in Japan: Who Wins and Why?

- Ministry of Justice – Commercial Registration Procedures (商業・法人登記手続)

- Companies Act Overview – Legislative Council Materials (法制審議会 会社法関連資料)

- Japanese Law Translation – Companies Act (English)