Apparent Authority in Japan: When Can a Company Be Bound by a Director Lacking Full Powers? The Role of Third-Party Negligence

Case: Action for Payment on a Promissory Note

Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench, Judgment of October 14, 1977

Case Number: (O) No. 106 of 1977

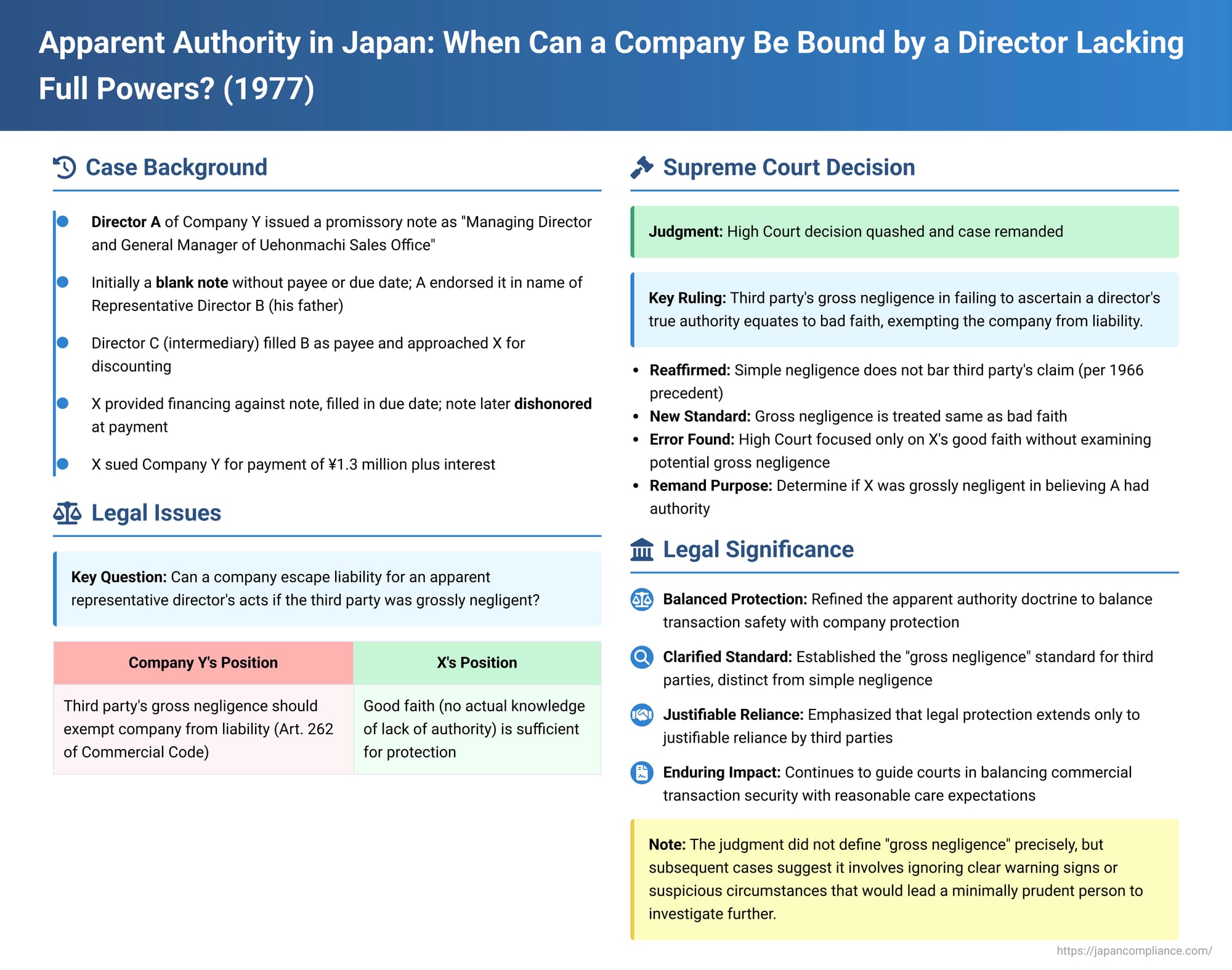

In the fast-paced world of business, third parties often rely on the titles and apparent authority of corporate officers when entering into transactions. Japanese company law, through the doctrine of "apparent representative director" (表見代表取締役 - hyōken daihyō torishimariyaku), generally holds a company liable for the actions of a director to whom it has given a title suggesting representative authority, even if that director technically lacks such power. However, this protection for third parties is not absolute. A crucial Supreme Court decision on October 14, 1977, clarified that while simple negligence on the part of a third party might not excuse the company, "gross negligence" by the third party in failing to recognize the director's lack of authority can indeed shield the company from liability.

A Promissory Note and a Question of Authority: Facts of the Case

The plaintiff, X, was the holder of a promissory note allegedly drawn by Company Y. The note had a complex history:

- Issuance: A, a director of Company Y, issued the promissory note. He did so using the title "Managing Director and General Manager of Company Y Uehonmachi Sales Office." The purpose of issuing the note was to secure a loan.

- Blank Note: Initially, key details on the note, such as the payee and the payment due date, were left blank.

- Endorsement and Brokering: A then signed and sealed a first endorsement on the note in the name of B, who was the actual Representative Director of Company Y and also A's father. A then handed the note to C, another director of Company Y, with a request to arrange financing using the note.

- Completion and Discounting: C subsequently filled in B (the Representative Director) as the payee on the note. C then approached X, who agreed to discount the note (provide financing against it). X filled in the payment due date.

- Dishonor: When the payment due date arrived, X presented the note at the designated place of payment, but it was dishonored (payment was refused).

Following the dishonor, X sued Company Y, seeking payment of the note's face value (1.3 million yen) plus accrued interest and damages. X's claim was based on the assertion that Company Y was liable as the drawer of the note due to A's actions.

The Lower Courts' Focus on "Good Faith"

The court of first instance (Osaka District Court, judgment dated January 30, 1973) found in favor of X. It held Company Y liable based on the provisions of the then-Commercial Code Article 262 (the predecessor to Article 354 of the current Companies Act concerning apparent representative directors). The court reasoned that for a company to be held responsible for the acts of an apparent representative director, it was sufficient that the third party (X, in this case) acted in "good faith" (i.e., was unaware that A lacked actual representative authority). The court specifically stated that the third party was not required to be free of negligence.

The appellate court (Osaka High Court, judgment dated September 29, 1976) upheld this decision, reaffirming that X's good faith was the determining factor for Company Y's liability.

The Company's Contention: Gross Negligence Matters

Company Y appealed to the Supreme Court. Its central argument was that the protection afforded by Article 262 should not extend to a third party who was "grossly negligent" in failing to ascertain the director's true authority.

The Supreme Court's Refinement: Introducing "Gross Negligence" as a Shield

The Supreme Court quashed the High Court's judgment and remanded the case back to the Osaka High Court for further proceedings.

Reasoning of the Apex Court: Balancing Reliance and Responsibility

The Supreme Court's reasoning introduced a significant nuance to the application of the apparent representative director doctrine:

- Liability to Good Faith Third Parties (with Simple Negligence): The Court began by reaffirming a principle from its prior jurisprudence (specifically, a Supreme Court, First Petty Bench judgment of November 10, 1966): A company's liability under the apparent representative director provision is owed to a "third party in good faith." As long as the third party acts in good faith (i.e., genuinely believes the director has authority), the company cannot escape liability under this provision even if the third party was (simply) negligent in not discovering the lack of authority.

- Purpose of the Doctrine: Protecting Justifiable Reliance: However, the Court then emphasized that the underlying purpose of this statutory provision is to protect the justifiable reliance of third parties.

- Gross Negligence Equated to Bad Faith: Building on this, the Supreme Court introduced a critical distinction: If a third party's failure to know about the director's lack of actual representative authority stems from their own "gross negligence" (重大な過失 - jūdai na kashitsu), then this situation should be treated in the same manner as if the third party had acted in "bad faith" (i.e., with actual knowledge of the lack of authority). In such cases of gross negligence by the third party, the company should be exempt from liability.

- Error of the High Court: The High Court had found that director A, who had been permitted by Company Y to use the title "Managing Director and General Manager of Company Y Uehonmachi Sales Office," issued the note without actual authority. It also found that X, when approached by director C to discount the note, believed A possessed representative authority and acquired the note without making any specific inquiries into A's actual powers. Based on X's good faith (lack of actual knowledge), the High Court had held Company Y liable.

The Supreme Court pointed out that Company Y had specifically argued in the High Court that X was grossly negligent. The High Court erred by imposing liability on Company Y solely on the basis of X's good faith, without making a determination as to whether X was also free of gross negligence. - Remand for Determination of Gross Negligence: Because the presence or absence of gross negligence on X's part was critical to determining Company Y's liability, and this issue had not been adequately addressed, the Supreme Court deemed it necessary to remand the case. The Osaka High Court was instructed to re-examine the facts specifically to determine if X's conduct amounted to gross negligence.

Analysis and Implications: Defining the Boundaries of Third-Party Protection

This 1977 Supreme Court judgment is a landmark in Japanese corporate law for its clarification of the subjective requirements for a third party seeking to hold a company liable under the apparent representative director doctrine.

- The Doctrine of Apparent Representative Director (Companies Act Article 354):

This doctrine, now enshrined in Article 354 of the Companies Act, is designed to protect third parties who enter into transactions in reliance on titles (such as President, Vice-President, CEO, Managing Director, etc.) that a company has allowed a director to use, where such titles would reasonably lead one to believe the director has authority to represent the company. If these conditions are met, the company can be held liable for the director's actions, even if the director did not, in fact, possess the specific representative authority for that transaction. The doctrine seeks to balance the safety of commercial transactions against the internal governance of companies.

The core elements are: (a) the company must have given the director a title that is recognizable as denoting representative authority (this involves both the existence of an outward appearance and some act of the company creating or permitting this appearance); (b) the director must have used this title in the transaction with the third party; and (c) the third party must have relied on this appearance in good faith and, as clarified by this judgment, without being grossly negligent.

Historically, this provision was introduced into the Commercial Code in 1938 to address issues where companies would allow non-representative directors to use impressive-sounding titles and then attempt to disavow transactions if they turned sour. The significance of the rule evolved, particularly after the board of directors system became mandatory in 1950. While Article 354 of the Companies Act no longer explicitly lists titles like "Managing Director" (senmu torishimariyaku) or "Executive Director" (jōmu torishimariyaku) as it did in the old Commercial Code, the principle remains: if a title, in its factual context, implies representative authority, the doctrine can apply. - The Third Party's Subjective State: From Good Faith to No Gross Negligence:

"Good faith" (zen'i) in this context simply means that the third party was not aware that the director lacked the proper authority. Before the 1977 Supreme Court judgment, there was some debate among legal scholars regarding the precise standard required of the third party:- Good faith alone is sufficient: This was a literal interpretation of the statutory text.

- Good faith and no (simple) negligence: This view argued that third parties should exercise a reasonable degree of diligence.

- Good faith and no gross negligence: This was an intermediate position.

A 1966 Supreme Court decision had indicated that a good-faith third party could hold the company liable even if they were (simply) negligent. However, that ruling did not explicitly address the issue of gross negligence, leaving room for uncertainty.

The 1977 Supreme Court judgment decisively settled this debate by establishing that while simple negligence does not bar a third party's claim, gross negligence does. This brought the standard for apparent representative director liability into closer alignment with similar principles in other areas of Japanese law, such as "name lending" (na-ita-gashi) liability, where a similar distinction is made. This was not a formal overruling of the 1966 case but rather a crucial clarification and refinement.

- Defining "Gross Negligence" (jūdai na kashitsu):

The 1977 judgment itself does not provide an exhaustive definition of "gross negligence" for the purposes of this doctrine. However, drawing from general legal principles and interpretations in other contexts (such as employer liability in tort law), gross negligence is understood as a more severe failing than simple negligence. It typically implies a significant departure from the standard of care that a reasonably prudent person would exercise under the circumstances, often bordering on recklessness or a willful disregard of obvious risks. It means failing to exercise even slight attention to circumstances that would have alerted a person to the potential lack of authority.

Subsequent lower court decisions grappling with this standard have shown that:- Gross negligence is often not found merely because a third party did not check the company's commercial登記簿 (company registry) to verify representative authority, especially if there were no other red flags. It has also not been found in some cases where there were minor irregularities in the transaction (like a handwritten amount on a promissory note or the use of generic stationery store forms for the note) if these irregularities were not directly indicative of a lack of representative authority.

- Conversely, gross negligence has been found in situations where there were clear and strong reasons for the third party to doubt the director's authority (e.g., knowledge that the director had recently stepped down as representative director, use of a highly unusual form for a promissory note, or direct warnings from other company officials), and the third party nonetheless failed to make basic inquiries or checks, such as consulting the company registry.

The general trend suggests that gross negligence is typically found only when the third party ignores clear warning signs or fails to take very basic precautionary steps in the face of suspicious circumstances that would make a minimally prudent person investigate further. The assessment often looks at the entire context of the transaction and the third party's reliance not just on the title, but on the overall appearance of authority.

- Apparent Representative Director Doctrine and the Company Registry:

A frequently debated issue is the interplay between the apparent representative director doctrine and the information publicly available in the company registry, which accurately lists the company's duly appointed representative director(s). If a third party fails to check this readily available public record, can they still claim to have justifiably relied on a misleading title?

Early on, some proposed a theory of "bad faith fiction" (akui gisei), suggesting that anyone who failed to check the registry should be legally presumed to know its contents (and thus be in bad faith if they relied on a contrary appearance). This was largely rejected as being too harsh on third parties and detrimental to the speed and efficiency of commercial transactions.

The prevailing view, supported by case law, is more nuanced. While failing to check the company registry is not, in itself, automatically considered gross negligence (it might constitute simple negligence in some contexts), if there are other suspicious circumstances surrounding the transaction or the director's claim of authority, then the failure to consult the registry as a basic verification step can indeed contribute significantly to a finding of gross negligence. - The Significance of the Remand:

The Supreme Court's decision to remand the case was crucial. It signaled that the High Court needed to conduct a thorough factual examination specifically focused on whether X's conduct—considering all circumstances, including the nature of the blank promissory note, the way it was endorsed, and the role of director C as an intermediary—rose to the level of gross negligence in believing that director A had the authority to bind Company Y to the note.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's judgment of October 14, 1977, marked an important development in the law of apparent representative directors in Japan. It clarified that while companies are generally bound by the actions of directors to whom they have given titles implying representative authority when dealing with good-faith third parties (even if those third parties are simply negligent), this protection does not extend to situations where the third party has been grossly negligent. By equating gross negligence with bad faith for the purposes of this doctrine, the Court reinforced the principle that legal protection is afforded to justifiable reliance. A third party who ignores significant red flags or fails to exercise even a minimal degree of prudence in the face of suspicious circumstances cannot expect to hold the company liable. This ruling continues to inform how Japanese courts balance the need to protect the safety and reliability of commercial transactions with the principle that parties should bear some responsibility for exercising reasonable care.