Antitrust Considerations in Japan: Beyond Cartels – Cooperatives, ESG, and Human Rights

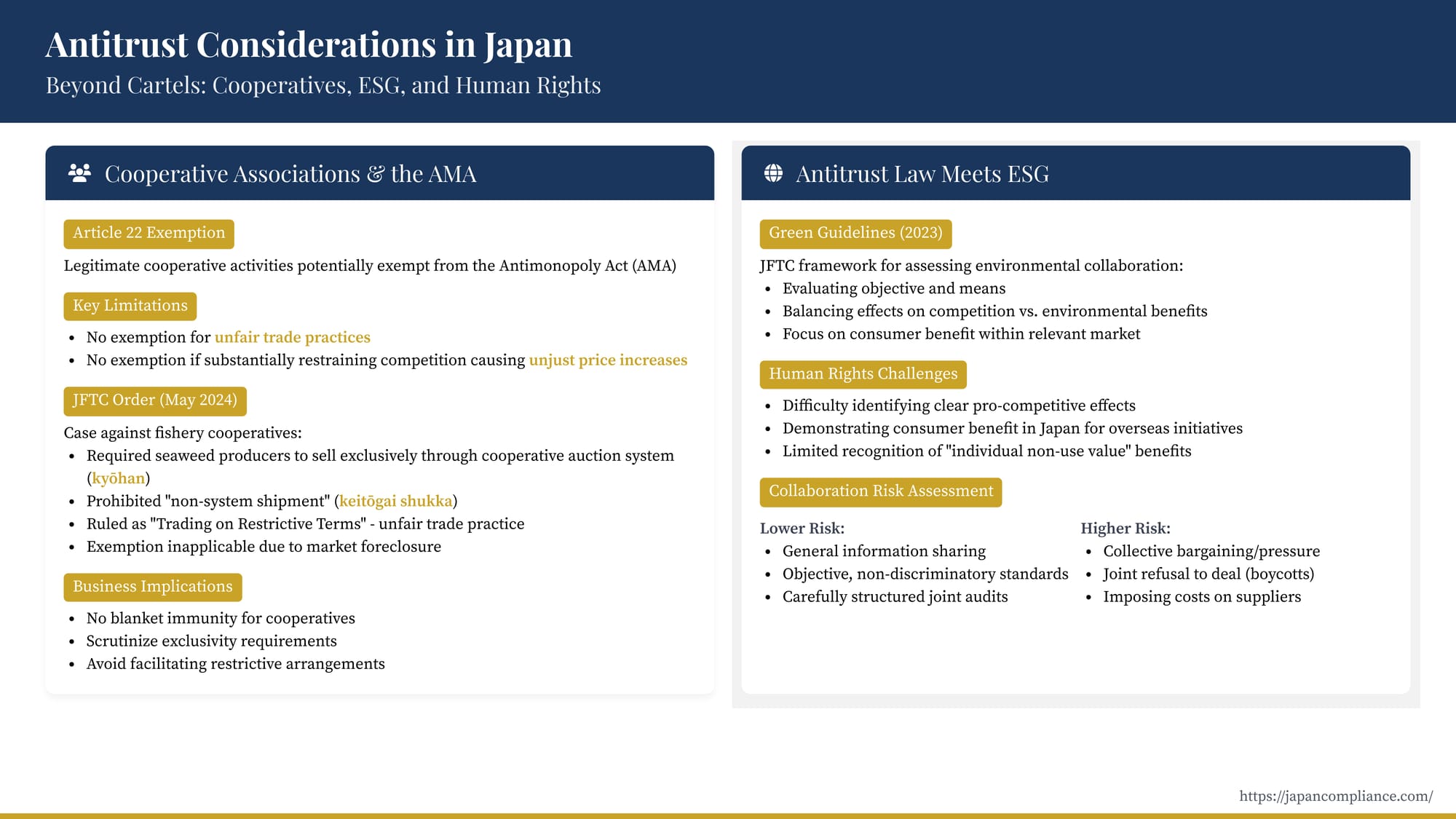

TL;DR: Japan’s Antimonopoly Act polices more than cartels—recent JFTC cases against fishery cooperatives show the limits of Article 22 exemptions, while ESG collaborations on human-rights due diligence face antitrust scrutiny under the Green Guidelines framework. Businesses must vet cooperative agreements, information sharing and boycott risks.

Table of Contents

- Introduction: Unique Facets of Japanese Competition Law

- Part 1: Cooperative Associations and the Antimonopoly Act

- Part 2: Antitrust Law Meets ESG – Evaluating Human Rights Initiatives

- Conclusion: Navigating Specialized Antitrust Terrain

Introduction: Unique Facets of Japanese Competition Law

While Japan's Antimonopoly Act (AMA - 独占禁止法, Dokusen Kinshi Hō) shares core principles with competition laws globally—prohibiting unreasonable restraints of trade like cartels, unfair trade practices, and monopolization—its application presents unique features and evolving challenges relevant to businesses operating in the Japanese market. Beyond standard merger reviews and cartel enforcement, companies need to be aware of how the Japan Fair Trade Commission (JFTC) approaches specific industry structures, like cooperative associations, and how antitrust principles are intersecting with burgeoning Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) initiatives, particularly concerning human rights in supply chains.

This article delves into two such areas highlighted by recent developments: first, the antitrust scrutiny applied to cooperative associations, illustrated by a 2024 JFTC decision involving fishery cooperatives; and second, the complex and still-developing interface between the AMA and corporate efforts related to human rights due diligence and sustainability collaborations. Understanding these nuances is crucial for navigating compliance and risk in Japan.

Part 1: Cooperative Associations and the Antimonopoly Act

Cooperative associations, such as agricultural cooperatives (農協, nōkyō) and fishery cooperatives (漁協, gyokyō), play a significant role in certain sectors of the Japanese economy. While they engage in commercial activities, their structure and purpose sometimes afford them specific treatment under the law.

The AMA Exemption and its Limits (Article 22)

Article 22 of the AMA provides a potential exemption for the legitimate activities of certain cooperatives established under specific enabling statutes (like the Fisheries Cooperative Act or the Agricultural Cooperative Act). This exemption recognizes the unique nature and objectives of cooperatives, such as improving the economic position of their members.

However, this exemption is not absolute. The proviso to Article 22 explicitly states that the exemption does not apply if the cooperative:

- Employs "unfair trade practices" (不公正な取引方法, fukōsei na torihiki hōhō); or

- Substantially restrains competition in a particular field of trade, resulting in an unjust increase in prices.

This means that even qualifying cooperatives can violate the AMA if their conduct falls foul of these conditions. Unfair trade practices, defined broadly in AMA Article 2(9) and detailed in JFTC General Designations, encompass actions like boycotts, discriminatory treatment, abuse of superior bargaining position, and trading on restrictive terms.

Case Study: Fishery Cooperative Restrictions (JFTC Order, May 15, 2024)

A recent JFTC action against a prefectural fishery federation (漁連, gyoren) and associated fishery cooperatives (gyokyō) provides a clear example of the limits of the cooperative exemption.

- The Conduct: The federation and cooperatives required their member seaweed producers (fishermen) to sell virtually all their harvested product exclusively through the cooperative-run auction system (a practice known as "system shipment" or 共販, kyōhan). Members were effectively prohibited from selling their seaweed through alternative channels ("non-system shipment" or 系統外出荷, keitōgai shukka), even for products that went unsold at the auction (札無品, fudanashi hin). This exclusivity was enforced through various means, including:

- Requiring members to sign pledges committing to 100% system shipment.

- Pressuring designated trading companies (指定商社), who were major buyers at the auction, to refrain from purchasing seaweed directly from fishermen outside the system (a practice called "shore buying" or 浜買い, hamagai).

- The fishermen's heavy dependence on the cooperatives for access to essential fishing rights made it practically impossible for them to resist these requirements.

- JFTC's Findings and Order: The JFTC investigated this arrangement and concluded that the conduct violated the AMA.

- Unfair Trade Practice: The forced exclusivity and restrictions constituted an "unfair trade practice," specifically categorized as "Trading on Restrictive Terms" (拘束条件付取引, kōsoku jōken tsuki torihiki), which falls under the general prohibition in AMA Article 19.

- Exemption Inapplicable: Because the cooperatives employed unfair trade practices, the Article 22 exemption did not shield their actions.

- Cease-and-Desist Order: The JFTC issued an order requiring the federation and a key cooperative to cease the restrictive practices, notify members and trading companies of the cessation, and implement compliance measures.

- Key Analytical Points:

- Focus on Substance: The JFTC identified the federation as the central actor imposing the restrictions, even though individual fishermen primarily interacted with their local cooperative. The pressure on trading companies was seen as reinforcing the core violation against the fishermen.

- Coercion Element: The restraint was considered effective not just due to contractual terms but because of the fishermen's dependence on the cooperatives for their livelihood (access to fishing rights). This highlights that de facto power imbalances can underpin a finding of restriction.

- Anticompetitive Effect: The primary harm identified was market foreclosure. By preventing fishermen from selling outside the system, the cooperatives excluded potential competing buyers (including the designated traders acting independently, or other processors/distributors) from accessing the seaweed supply. This restriction harmed competition in the relevant market, likely defined as the market for procuring seaweed from producers in that specific region.

Implications for Businesses Interacting with Cooperatives

This case underscores several important points for businesses:

- No Blanket Immunity: Cooperative associations are not exempt from the AMA if their actions constitute unfair trade practices or unduly harm competition.

- Scrutinize Exclusivity Requirements: Attempts by cooperatives to impose exclusive selling obligations on their members, restrict access to alternative sales channels, or dictate terms to buyers in ways that limit competition can raise serious AMA concerns.

- Beware of Facilitating Restrictions: Businesses buying from or dealing with cooperatives should avoid participating in arrangements that reinforce potentially anticompetitive restrictions imposed by the cooperative (e.g., agreeing not to source directly from members if the cooperative demands exclusivity).

- Broader Applicability: Similar issues have arisen with agricultural cooperatives restricting non-system shipments (as seen in the earlier Tosa Aki Nōkyō case referenced in legal commentary), indicating this is a recurring theme in Japanese antitrust enforcement concerning cooperatives.

Part 2: Antitrust Law Meets ESG – Evaluating Human Rights Initiatives

A rapidly developing area globally is the intersection of competition law and corporate collaboration on Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) objectives. While cooperation on sustainability goals is often encouraged by policymakers, it can sometimes involve agreements or practices among competitors that raise antitrust flags. Japan is beginning to grapple with these issues, particularly in the context of environmental sustainability and, more nascently, human rights.

The JFTC's "Green Guidelines" Framework

In March 2023 (with minor revisions in April 2024), the JFTC published its "Guidelines Concerning the Activities of Enterprises, etc. Toward the Realization of a Green Society under the Antimonopoly Act" (通称「グリーンガイドライン」 or "Green Guidelines," GG). These guidelines provide a framework for assessing collaborations aimed at environmental sustainability.

The GG's basic approach involves:

- Evaluating the Objective and Means: Assessing the legitimacy of the environmental goal ("reasonableness of the objective") and whether the chosen collaborative method is necessary and proportionate ("appropriateness of the means," considering less restrictive alternatives).

- Balancing Effects: Weighing the potential pro-competitive effects and environmental benefits against the potential restrictions on competition.

- Focus on Consumer Benefit: Traditionally, competition law focuses on benefits accruing to consumers within the relevant market (e.g., lower prices, better quality, more innovation).

Applicability to Human Rights Collaborations?

The Green Guidelines themselves explicitly state (in Note 12) that the framework presented might be applicable to collaborations pursuing other socially desirable objectives linked to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), such as respecting human rights. The JFTC commentary on the draft GG further noted that the applicability was likely high for initiatives addressing social issues like human rights.

However, applying the GG framework directly to human rights initiatives, especially those focused on international supply chains, presents challenges noted in legal analyses:

- Identifying Pro-Competitive Effects: Collaborations focused on environmental goals might lead to new "green" technologies or products perceived as superior by consumers, thus having arguably pro-competitive effects. It's less clear whether agreements focused purely on improving human rights standards in overseas supply chains (e.g., agreeing not to use suppliers employing forced labor) readily generate similar types of innovation or product differentiation benefits traditionally recognized by competition law.

- Demonstrating Consumer Benefit (in Japan): A significant hurdle arises when human rights initiatives target conditions outside Japan. The traditional competition law focus requires benefits for consumers in the relevant market (i.e., Japan). Can improved labor conditions in a foreign factory be considered a direct benefit to Japanese consumers purchasing the end product?

- European competition law discourse (e.g., in the EU's Horizontal Guidelines on sustainability agreements) grapples with this, distinguishing between:

- Individual use value benefits (e.g., a product is demonstrably higher quality due to better standards).

- Individual non-use value benefits (e.g., consumers derive value from knowing a product was made ethically and are willing to pay more for it, even if the product quality is unchanged).

- Collective benefits (e.g., broader societal benefits like reduced pollution, which might benefit consumers indirectly, even those unwilling to pay a premium).

- Japanese legal commentary suggests that for overseas human rights initiatives, only the "individual non-use value" (②) is potentially relevant, as "collective benefits" (③) are unlikely to accrue primarily to Japanese consumers, and direct "use value" benefits (①) are often absent. Establishing sufficient consumer willingness-to-pay in Japan for ethically sourced goods (demonstrating non-use value) might be difficult.

- European competition law discourse (e.g., in the EU's Horizontal Guidelines on sustainability agreements) grapples with this, distinguishing between:

Given these challenges, while the JFTC acknowledges potential applicability, directly transposing the Green Guidelines framework to human rights collaborations requires careful consideration.

Assessing Specific Human Rights Initiatives under the AMA

Despite the uncertainties, we can analyze potential human rights collaborations by drawing parallels with AMA principles and the GG's approach to specific conduct:

- Information Sharing: Sharing general information about human rights risks in certain regions or sectors, or non-confidential summaries of audit findings (without naming specific suppliers inappropriately), might be permissible if it avoids facilitating collusion on purchasing decisions or prices (cf. GG Case Example 55). Sharing supplier-specific sensitive data carries higher risks.

- Setting Standards: Developing industry standards for human rights compliance (e.g., a code of conduct prohibiting child labor) could be pro-competitive if the standards are objective, non-discriminatory, transparent, and participation is voluntary. However, if standards effectively exclude certain suppliers without objective justification or are used to coordinate purchasing behavior, they risk being deemed anticompetitive boycotts or restrictive practices (cf. GG Case Examples 17, 23). Certification or labeling schemes (like Fair Trade labels discussed in EU examples) might be permissible if they primarily provide information to consumers, market shares are not excessive, and they don't involve price coordination.

- Joint Audits/Due Diligence: Collaborating on supplier audits or due diligence efforts can create efficiencies but carries risks if sensitive cost or supplier information is exchanged, leading to coordinated purchasing or pricing. Structuring these collaborations carefully (e.g., using independent third parties) is crucial.

- Collective Bargaining/Pressure: Jointly negotiating with suppliers over human rights improvements or collectively pressuring suppliers to adopt certain standards raises significant risks of buyer cartels or concerted practices, especially if it impacts purchasing prices or supplier choices.

- Joint Refusal to Deal (Boycotts): Agreeing among competitors to stop sourcing from suppliers found to violate human rights standards is highly likely to be viewed as an illegal group boycott under the AMA, unless perhaps narrowly targeted at suppliers involved in egregious, internationally condemned violations (akin to complying with binding international sanctions, though this is a complex area). Notably, Japan's official guidelines on human rights due diligence (published by METI/MOFA) generally advise companies to engage with problematic suppliers to seek improvement first, viewing termination of the business relationship as a last resort. This aligns with the view that immediate boycotts are disfavored.

- Imposing Costs on Suppliers: Using a dominant bargaining position to unilaterally force suppliers to bear the full cost of meeting human rights standards or audits without fair negotiation could potentially constitute an Abuse of Superior Bargaining Position, an unfair trade practice under the AMA (cf. GG Case Examples 71, 72).

Implications for Businesses

- Antitrust is Relevant to ESG: Companies pursuing collaborative ESG initiatives, including human rights due diligence, must consider potential AMA implications.

- Collaboration Risks: Agreements with competitors regarding sourcing standards, supplier selection/exclusion, joint negotiations, or information exchange require careful antitrust vetting.

- Abuse of Dominance: How companies interact with suppliers regarding ESG compliance costs and requirements can also raise AMA issues under the abuse of superior bargaining position doctrine.

- Guidance Gap: Unlike environmental collaborations covered by the Green Guidelines, there is currently no specific JFTC guidance dedicated to human rights initiatives, creating some uncertainty. Businesses undertaking significant collaborations may consider informal consultation with the JFTC.

- Method Matters: While the goal of respecting human rights is encouraged by government policy, the collaborative methods used must align with competition law principles.

Conclusion: Navigating Specialized Antitrust Terrain

Japan's Antimonopoly Act landscape includes important features beyond core cartel and merger enforcement. The recent JFTC action against fishery cooperatives demonstrates that cooperative associations are subject to AMA scrutiny, particularly when their conduct involves unfair trade practices that restrict member activities or foreclose competitors. Foreign companies dealing with Japanese cooperatives should be mindful of these potential restrictions.

Simultaneously, the intersection of antitrust law with corporate ESG initiatives, especially human rights due diligence in global supply chains, is an emerging area of complexity. While the JFTC's Green Guidelines offer a potential framework, its direct applicability and the assessment of consumer benefits for human rights collaborations remain uncertain. Companies engaging in joint ESG efforts, particularly those involving competitor collaboration on standards or sourcing decisions, must tread carefully to avoid infringing the AMA.

For businesses operating in Japan, staying informed about these specialized areas of antitrust enforcement and policy—from the unique status of cooperatives to the evolving treatment of sustainability collaborations—is essential for effective compliance and strategic decision-making. Seeking specialized legal advice is recommended when navigating these complex terrains.

- Fortifying the Chain: Japan’s Regulations on Critical Supply Chains and Infrastructure

- Navigating Japan’s New Security-Clearance System

- EU Battery Regulation: Global Reach—Impact on US & Japanese Supply Chains

- Japan Fair Trade Commission — Green Guidelines (JP)

https://www.jftc.go.jp/pressrelease/2024/April/green_guidelines.html