Anticipating an Attack: A 2017 Japanese Supreme Court Case Redefines Self-Defense

Decision Date: April 26, 2017

The right to self-defense is a fundamental principle in nearly every legal system, recognizing an individual's right to protect themselves from harm. A core element of this right is "imminence"—the threat must be immediate, happening now or about to happen. This requirement ensures that self-defense is a last resort in an emergency, not a license for preemptive violence. But what happens when the lines of imminence are blurred? What if a person anticipates an attack, knows it is coming, and instead of avoiding it, goes to meet the threat head-on? Does this foreknowledge negate the "imminence" of the danger and forfeit the right to self-defense?

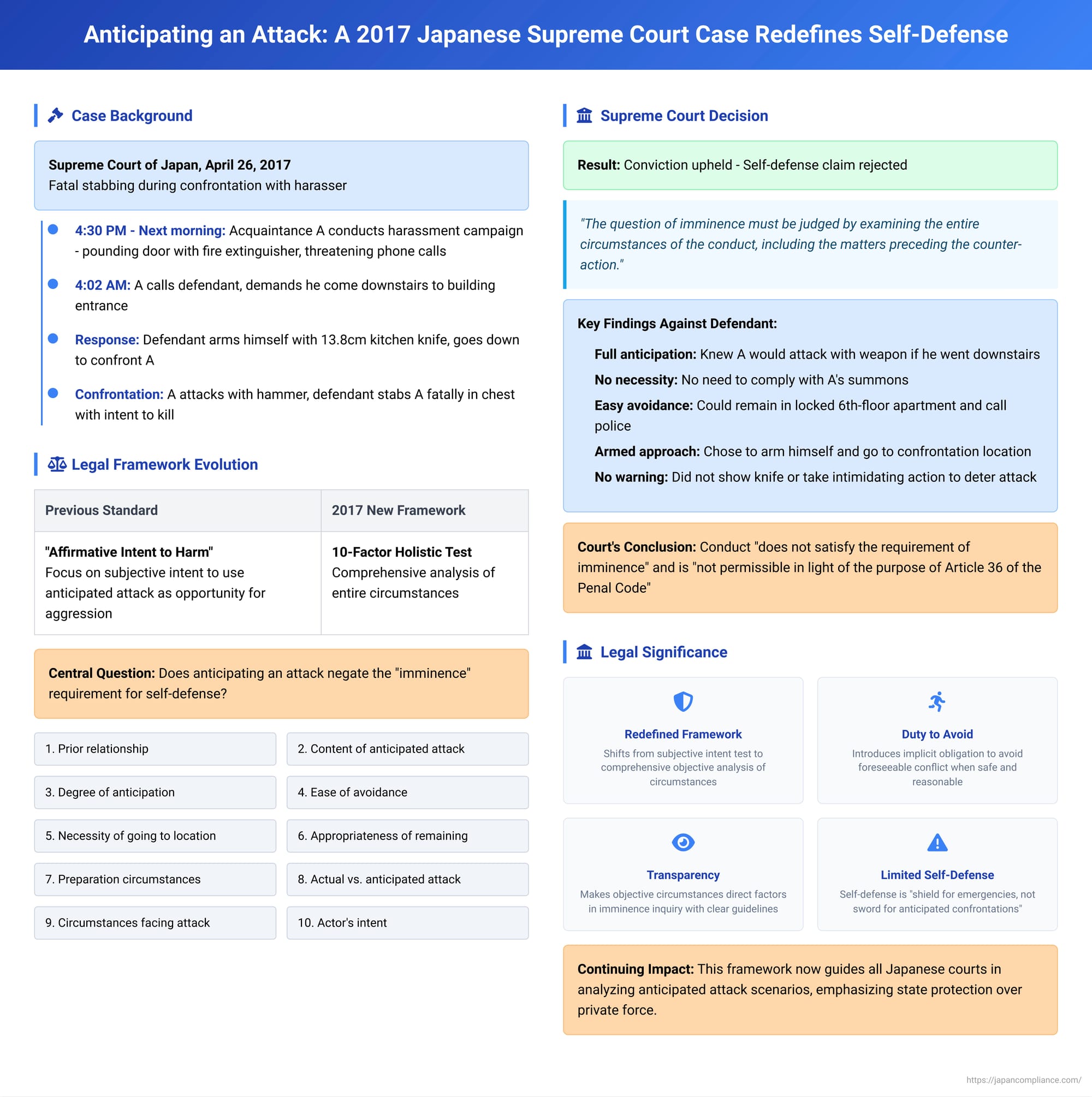

On April 26, 2017, the Supreme Court of Japan addressed this very question in a landmark decision that has reshaped the landscape of self-defense law. The case, which arose from a violent confrontation born out of a campaign of harassment, saw the Court move beyond a simple inquiry into the defender's subjective intent and establish a detailed, multi-factor framework for analyzing the legitimacy of self-defense in cases involving an anticipated attack.

The Factual Background: A Harassing Caller and a Fateful Confrontation

The case began with a prolonged and bizarre campaign of harassment directed at the defendant. An acquaintance, A, baselessly accused the defendant of some unknown wrongdoing. The harassment escalated over a period of many hours, starting around 4:30 PM one afternoon and continuing into the next morning. During this time, A pounded on the door of the defendant's sixth-floor apartment with a fire extinguisher and barraged him with more than a dozen furious and threatening phone calls, at one point vowing, "I'm coming to get you now, so you just wait. I'm gonna make you pay."

The situation came to a head at approximately 4:02 AM. A called the defendant, who was in his home, and told him he was waiting in front of the apartment building, demanding that the defendant come down. The defendant, angered by the hours of harassment, decided to go. He took a kitchen knife with a 13.8 cm (approx. 5.4 inch) blade from his home, wrapped it in a towel, and tucked it into the back of his waistband before heading down to the street.

Upon seeing the defendant, A rushed towards him holding a hammer. The defendant, for his part, did not brandish the knife or take any other intimidating action to warn A off. Instead, he walked towards A. As A swung the hammer at him, the defendant blocked the attack while simultaneously drawing the knife. With the intent to kill, he then stabbed A once, forcefully, in the left side of the chest, inflicting a fatal wound.

The Lower Courts: A Focus on "Affirmative Intent to Harm"

In the lower courts, the defendant argued that his actions constituted self-defense or, at a minimum, excessive self-defense. Both the trial court and the high court rejected this argument, finding that the defendant possessed an "affirmative intent to harm" (sekkyokuteki kagai ishi). This legal concept, established in a 1977 Supreme Court precedent, effectively disqualifies a self-defense claim if it is found that the defender used an anticipated attack as an opportunity to proactively and aggressively injure the attacker. The lower courts concluded that the defendant's decision to arm himself with a knife and go down to the street to confront A, rather than remaining in his home and calling the police, demonstrated this disqualifying intent.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Decision: A New, Holistic Framework

The Supreme Court upheld the defendant's conviction, but in doing so, it established a new, more comprehensive legal framework for analyzing such cases.

The Core Principle of Self-Defense:

The Court began by reaffirming the fundamental purpose of the right to self-defense under Article 36 of the Penal Code: it is an "exceptional allowance for a private citizen's counter-action" that is permitted only in an "emergency situation of an imminent and unjust attack, when it cannot be expected that one could seek the legal protection of a public authority."

A New Test for Anticipated Attacks:

The Court then declared that merely anticipating an attack does not automatically disqualify a self-defense claim. Instead, the question of imminence must be judged by examining "the entire circumstances of the conduct, including the matters preceding the counter-action." It then laid out a non-exhaustive, ten-point list of factors for courts to consider on a case-by-case basis:

- The prior relationship between the actor and the other party.

- The content of the anticipated attack.

- The degree to which the attack was anticipated.

- The ease with which the attack could have been avoided.

- The necessity of going to the location where the attack was to occur.

- The appropriateness of remaining at the location of the attack.

- The circumstances of the preparation for the counter-action (especially the presence of weapons and their nature).

- The difference, if any, between the actual attack and the anticipated attack.

- The circumstances in which the actor faced the attack.

- The actor's intent at the time of the incident.

Applying the New Framework to the Facts:

The Supreme Court then applied this new, holistic test to the defendant's conduct and found his claim of self-defense wanting. The Court highlighted that:

- The defendant "fully anticipated" that if he went downstairs, A would attack him with a weapon.

- There was "no necessity to comply with A's summons."

- It would have been "easy" for the defendant to "remain in his home and receive the assistance of the police."

- Despite this, he armed himself with a knife and went to the location where A was waiting.

- When A attacked with a hammer, the defendant did not engage in any "intimidating action such as showing the knife" but instead "approached A" and immediately used lethal force.

Viewing these preceding circumstances and the act as a whole, the Court concluded that the defendant's conduct was "not permissible in light of the purpose of Article 36 of the Penal Code" and therefore "does not satisfy the requirement of imminence."

A Deeper Analysis: The Evolution of "Imminence"

This 2017 decision represents a significant evolution in Japanese self-defense law, shifting the focus from a narrow, subjective inquiry to a broad, objective analysis.

From "Affirmative Intent" to a Multi-Factor Test:

Previously, the key to disqualifying a self-defense claim in an anticipated attack scenario was proving the defender had an "affirmative intent to harm." While this sounds like a purely psychological test, legal commentary notes that, in practice, courts have long inferred this subjective intent from objective factors like the ease of avoidance, the choice to arm oneself, and the nature of the confrontation. The 2017 ruling does not abolish the "affirmative intent" test but rather reframes the analysis. It makes those objective circumstances direct factors in the imminence inquiry itself, creating a more transparent and structured legal standard.

The Implied "Duty to Avoid":

A key theme running through the Court's ten-point framework is the idea of avoidance. Factors like the "ease of avoidance," the "necessity of going to the location," and the "appropriateness of remaining" all point to a critical question: Did the defendant have a reasonable opportunity to prevent the confrontation altogether? This introduces a concept akin to a "duty to retreat" or, more accurately, a duty to avoid a foreseeable conflict when it is safe and easy to do so. The Court found that the defendant's ability to simply stay in his locked sixth-floor apartment and call the police was a decisive factor weighing against his claim. This duty is not absolute; legal scholars note that expecting a person to flee their own home or workplace would often be an unreasonable burden, but in this case, the option was both safe and simple.

Distinction from "Provoked" Self-Defense:

This framework for anticipated attacks should be distinguished from the separate legal doctrine of "provoked attack" (jishō shingai). As clarified in a 2008 Supreme Court case, the provoked attack doctrine applies when the defender's own prior wrongful act instigates the attack against them. The 2017 ruling, in contrast, applies to cases where the defender did not necessarily provoke the attack but knew it was coming. The two doctrines can now be applied in parallel by courts depending on the specific facts of a case.

Conclusion: A New Standard of Clarity for Self-Defense

The 2017 Supreme Court decision provides a comprehensive and modern framework for analyzing one of the most difficult questions in self-defense law. By shifting from a singular focus on the defender's subjective intent to a holistic, multi-factor analysis of the entire situation, the Court has brought greater clarity and transparency to the doctrine of imminence. The ruling sends a strong message that the right to self-defense is a shield for emergencies, not a sword for anticipated confrontations. When an individual has a safe and easy path to avoid a known danger, especially by relying on the protection of the state, the choice to instead arm oneself and walk willingly into that danger will likely be seen not as a defense of self, but as an act of aggression.