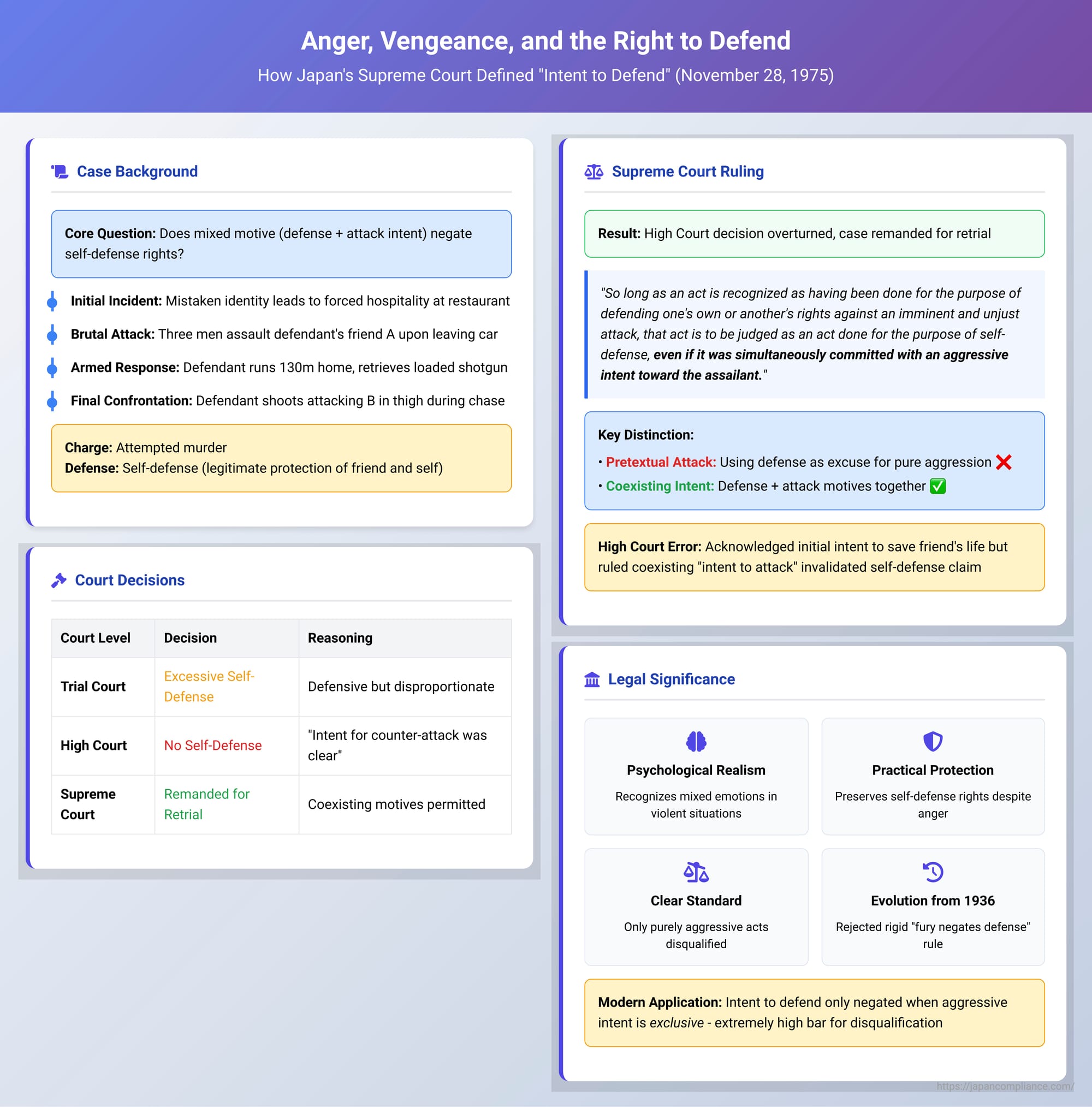

Anger, Vengeance, and the Right to Defend: How Japan's Supreme Court Defined "Intent to Defend"

Decision Date: November 28, 1975

The right to self-defense often conjures an image of a purely defensive act—a reluctant response to unprovoked aggression, undertaken with the sole motive of self-preservation. But reality is rarely so clean. Violent confrontations are emotionally charged events, and a person's reaction is often a complex cocktail of fear, anger, and a desire for retribution. This raises a critical legal question: if a person acts with mixed motives, does the presence of an "intent to attack" automatically nullify their right to self-defense?

On November 28, 1975, the Supreme Court of Japan issued a landmark decision that directly addressed this question. The case, arising from a brutal roadside assault and a subsequent armed confrontation, established the crucial principle that a defensive motive can coexist with an aggressive one. In doing so, the Court adopted a psychologically realistic view of self-defense, acknowledging that the right to protect oneself is not forfeited simply because the act of defense is accompanied by anger or a will to fight back.

The Factual Background: A Night of Escalating Violence

The incident began with a minor mistake that spiraled into a night of extreme violence. The defendant and his friend, A, were driving when they mistakenly called out to a group of three men—B and his companions—thinking they were acquaintances. The group took offense, accosted the defendant and A, and forced them to provide food and drinks at a nearby restaurant.

After this coerced hospitality, the defendant and A drove the three men to their destination. The moment B and his friends got out of the car, they launched a vicious and unprovoked attack on A. They relentlessly punched and kicked the defenseless A in the face and abdomen.

Watching this brutal assault, the defendant became convinced that A's life was in danger. He decided he had to rescue his friend. He ran approximately 130 meters back to his home, retrieved his younger brother's shotgun, and loaded it with four rounds of live ammunition. He disengaged the safety mechanism, put a spare shell in his shirt pocket, and rushed back to the scene.

By the time the defendant returned, however, the scene had changed. A had managed to escape his attackers on his own and had taken refuge in a nearby house. When the defendant arrived, both A and the assailants were gone. Believing his friend had been abducted, the defendant began searching the area. He soon spotted B's wife on the street and grabbed her arm, intending to ask where A had been taken. She screamed.

Hearing her scream, B came running towards the defendant, shouting, "You bastard, I'll kill you!" B gave chase. The defendant retreated for about 11 meters, yelling, "Stay back!" As B closed the distance and was about to catch him, the defendant, knowing it could be fatal, turned and fired the shotgun from his hip. The blast struck B in the left thigh, inflicting a serious injury that required approximately four months of medical treatment. The defendant was charged with attempted murder.

The Journey Through the Courts: A Focus on the Defendant's Mindset

The case hinged on whether the defendant's final act of shooting B could be considered self-defense. The lower courts were divided.

- The Trial Court: The first-instance court found the defendant guilty but applied the doctrine of excessive self-defense (kajō bōei). This legal doctrine in Japan acknowledges that the act was defensive in nature but that the means used were disproportionate to the threat. It typically allows for a reduced sentence or even an acquittal depending on the circumstances.

- The High Court: The prosecution appealed, and the High Court reversed the trial court's finding. The High Court took a holistic view of the defendant's actions, from the moment he decided to get the gun until the final shot was fired. It concluded that the defendant's "intent for a counter-attack was clear" and that he did not act for the purpose of defending himself against B's final charge. The court held that there was "no room for the notion of self-defense" and therefore no basis for finding even excessive self-defense.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Ruling on "Intent to Defend"

The Supreme Court overturned the High Court's decision and sent the case back for retrial. In its ruling, it provided a definitive statement on the role of a defender's subjective intent.

The Core Legal Principle:

The Court declared that an act of self-defense is not automatically negated just because the defender also has an aggressive motive. The key passage states:

"So long as an act is recognized as having been done for the purpose of defending one's own or another's rights against an imminent and unjust attack, that act is to be judged as an act done for the purpose of self-defense, even if it was simultaneously committed with an aggressive intent toward the assailant."

Distinguishing Legitimate Defense from a Pretext for Attack:

To clarify this principle, the Court drew a crucial distinction:

- Pretextual Attack: An act "done under the pretext of defense to affirmatively attack an assailant" is not true self-defense because it lacks a genuine intent to defend.

- Coexisting Intent: However, an act where the "intent to defend and the intent to attack coexist" is not an act that lacks the intent to defend and can be evaluated as self-defense.

The Supreme Court criticized the High Court for acknowledging that the defendant initially set out to save his friend's life, yet ruling that his coexisting "intent to attack" invalidated his claim to self-defense. This, the Supreme Court held, was an error in the interpretation of Article 36 of the Penal Code (the self-defense statute).

A Deeper Dive: The Evolution of "Intent to Defend" in Japanese Law

This 1975 ruling was the culmination of a long evolution in Japanese case law regarding the subjective element of self-defense, known as the "intent to defend" (bōei no ishi).

Early case law was notoriously strict. A 1936 judgment from the pre-war Daishin-in held that an act committed out of "fury" could not be considered self-defense. This standard was widely criticized as being psychologically unrealistic, as anyone facing a violent attack is likely to feel anger, fear, or a mix of powerful emotions.

A 1971 Supreme Court decision began to soften this rigid stance, ruling that acting out of "fury or agitation" does not automatically negate the intent to defend. This paved the way for the 1975 decision in this case, which went a step further and explicitly permitted the coexistence of defensive and aggressive motives.

Legal scholarship has since tried to distill the precise meaning of this "intent to defend." It is clearly more than simply being aware that one is in a self-defense situation. If it were, then even an act committed with purely aggressive intent would qualify. On the other hand, it is less than a requirement that defense be the sole, pure motive. The prevailing understanding is that the "intent to defend" is a general "intent to respond to the attack" or a "simple psychological state of trying to avoid the infringement."

Later Supreme Court cases have clarified that the intent to defend is only truly negated when the aggressive intent is exclusive—that is, when the defensive motive is essentially zero and the defender is acting "solely for the purpose of attack." This makes the bar for negating the intent to defend extremely high. In practice, as long as some defensive purpose exists, no matter how mixed with anger or a desire to fight back, the requirement is met.

Conclusion: A Realistic Standard for Imperfect Situations

The 1975 Supreme Court decision is a landmark because it infused the law of self-defense with a dose of psychological realism. It recognized that human beings in violent, life-threatening situations do not act with the clean, singular motives of a legal hypothetical. Fear coexists with anger; the will to survive coexists with the will to harm the attacker.

By ruling that an "intent to attack" does not automatically cancel out an "intent to defend," the Court ensured that the right to self-defense remains a practical and accessible reality. The law, as clarified in this case, does not demand purity of motive from those facing an imminent threat. It only denies the right of self-defense when the claim is a sham—a mere pretext for what is, in truth, a purely aggressive and malicious attack. This nuanced understanding ensures that the law protects individuals forced to react in the messy, emotionally charged, and imperfect circumstances of real-world violence.