Anesthesiologist's Duty and Causation: Japan's Supreme Court on Fatal Overdose During Surgery

Date of Judgment: March 27, 2009 (Heisei 21)

Case Reference: Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench, 2007 (Ju) No. 783

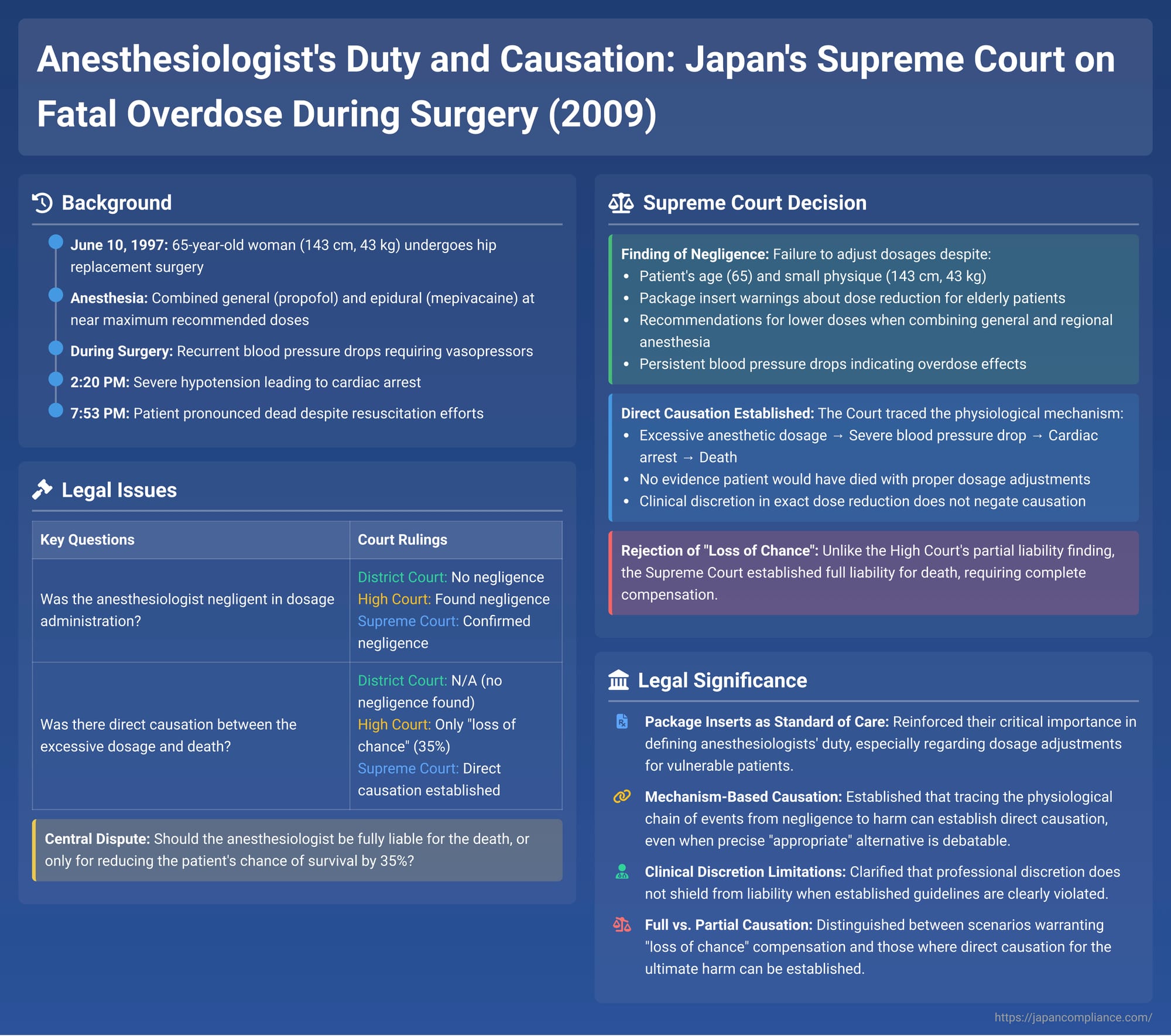

In a significant medical malpractice decision issued on March 27, 2009, the Supreme Court of Japan addressed the negligence of an anesthesiologist in a case involving the death of a patient during hip replacement surgery. The Court found that the administration of anesthetic drugs near or exceeding recommended limits, without adequate consideration for the patient's specific characteristics, constituted negligence. Crucially, it also affirmed a direct causal link between this negligence and the patient's death, thereby overturning a High Court decision that had only recognized a "loss of chance" of survival. This case underscores the critical importance of adhering to drug dosage guidelines and patient-specific adjustments in anesthesia.

Factual Background: A Routine Surgery with a Tragic Outcome

The patient, A, was a 65-year-old woman, relatively small in stature (143 cm, 43 kg). She suffered a fracture of her left femur and was scheduled for an artificial femoral head replacement surgery on June 10, 1997 (Heisei 9), at a prefectural hospital operated by defendant Y. Apart from osteoporosis, Patient A was in good general health, and her pre-operative vital signs were normal. She expressed to the anesthesiologist, Dr. B, a desire for complete pain relief during the surgery. In response, Dr. B opted for a combination of general anesthesia and regional (epidural) anesthesia.

Anesthesia Administration:

- General Anesthesia: Dr. B used propofol (intravenous) for induction and maintenance, along with ketamine hydrochloride (intravenous) and nitrous oxide (inhalation).

- Regional Anesthesia: An epidural block was administered using mepivacaine hydrochloride.

- Dosage Concerns: The dosages of propofol and mepivacaine used by Dr. B were near the upper limits recommended in their respective package inserts (能書 - nōgaki) and prevailing academic guidelines. The judgment details that for propofol, the continuous infusion rate, at certain points, slightly exceeded the usage examples provided in its package insert for the maintenance phase, especially considering the combined use with epidural anesthesia which typically allows for lower doses of general anesthetics. For mepivacaine, the total dose (400mg via epidural catheter) was at the higher end of the usual adult range (200-400mg for 2% solution) indicated in its package insert.

Intraoperative Events:

- Patient A was brought into the operating room around 1:15 PM. Anesthesia induction began around 1:25 PM.

- Initial blood pressure readings after induction showed drops (e.g., to 75/45 mmHg at 1:37 PM, 80/50 mmHg at 1:48 PM). Dr. B administered vasopressors (drugs to raise blood pressure, specifically etilefrine hydrochloride) on each occasion, temporarily restoring blood pressure to over 100 mmHg systolic.

- The surgery, performed by Dr. S, commenced at 1:55 PM.

- Further blood pressure drops occurred (e.g., 78/40 mmHg at 2:00 PM, 90/42 mmHg at 2:05 PM). Around 2:05 PM, Dr. B started an IV drip containing a combination of vasopressors (methoxamine hydrochloride and etilefrine hydrochloride) to provide more sustained blood pressure support. Blood pressure recovered to 112/55 mmHg at 2:10 PM.

- However, Patient A's blood pressure subsequently began to fall sharply again, dropping to 80/44 mmHg by 2:15 PM.

- Around 2:18-2:19 PM, the pulse oximeter reportedly failed to detect a pulse wave. Dr. B, palpating the carotid artery, found no pulse by 2:20 PM. The automated blood pressure monitor also failed to display a reading. The electrocardiogram (ECG) showed abnormal patterns, including frequent ventricular premature contractions.

- At approximately 2:22 PM, Patient A went into ventricular fibrillation, effectively a cardiac arrest ("the present cardiac arrest").

Resuscitation Efforts and Death:

- From around 2:20 PM, the medical team, led by Dr. B, initiated emergency measures. Propofol and ketamine infusions were stopped, 100% oxygen was administered, and the vasopressor drip was accelerated, along with IV administration of cardiac stimulants.

- The surgeon, Dr. S, was instructed to stop the operation and close the surgical wound.

- An endotracheal tube was inserted. Cardiac massage (chest compressions) was started sometime close to 2:30 PM, after the surgical wound was closed. Other resuscitation measures included administration of cardiac stimulants and defibrillation.

- Around 2:50 PM, a pulse became palpable, and cardiac massage was discontinued. However, the ECG continued to show abnormal rhythms, and blood pressure remained very low (60-40/20-10 mmHg).

- By about 4:05 PM, blood pressure stabilized somewhat at a low level (80-70/20 mmHg). Spontaneous respiration returned around 4:30 PM.

- The medical team decided to perform a CT scan to investigate the cause of the cardiac arrest. Patient A was moved to the CT room around 4:35 PM. However, shortly after the scan began, her blood pressure dropped again, and she suffered another cardiac arrest.

- Despite renewed resuscitation efforts (adrenaline, cardiac massage, defibrillation), Patient A was pronounced dead at 7:53 PM. No autopsy was performed.

Legal Claim and Defense

Patient A's heirs (plaintiffs X1, X2, and X3) filed a lawsuit against Y, the operator of the prefectural hospital, seeking approximately 42.66 million yen in damages based on tort (negligence). They argued that the negligence of the hospital's medical staff, primarily Anesthesiologist B, caused Patient A's death.

Plaintiffs' Allegations of Negligence:

- Anesthetic Overdose and Improper Blood Pressure Management: The core claim was that Dr. B administered excessive doses of anesthetic drugs, particularly given Patient A's age, small physique, and the combined use of general and epidural anesthesia, and failed to manage her falling blood pressure appropriately.

- Inadequate Post-Cardiac Arrest Measures: They also alleged deficiencies in the resuscitation efforts, including a delay in starting cardiac massage, failure to diagnose a potential tension pneumothorax, and a delay in transferring Patient A to the CT room.

Defendant's (Y Hospital Operator) Defense:

Y denied negligence on the part of its medical staff. It primarily argued that Patient A's cardiac arrest and subsequent death were not caused by the anesthesia but by a sudden, unpredictable, and unpreventable condition known as fulminant fat embolism syndrome (FFES). FFES can occur during orthopedic surgery involving bone marrow (like hip replacement), where fat droplets from the marrow enter the bloodstream, travel to the lungs, and cause acute pulmonary vascular obstruction leading to rapid cardiac failure.

Lower Court Proceedings: Diverging Views on Negligence and Causation

- First Instance (Tokyo District Court): The District Court found no negligence on the part of the medical team and dismissed the plaintiffs' claim entirely.

- High Court (Tokyo High Court): The High Court took a more complex view:

- (A) Cause of Death Determined: The High Court inferred that the anesthetic drugs administered were the primary cause of Patient A's cardiac arrest, and that this cardiac arrest was the initiating event leading to her death. It explicitly rejected the defendant's theory that FFES was the cause of death.

- (B) Specific Negligence Identified: The High Court found Anesthesiologist B negligent on two main counts:

- Failure to Tailor Anesthetic Dosage: Dr. B failed to adequately consider Patient A's individual characteristics (age 65, small stature) when determining the dosages of propofol and mepivacaine, especially in the context of their combined use. Package inserts for both drugs contained cautions regarding dosage reduction in elderly patients and when used in combination.

- Delayed Cardiac Massage: The medical team delayed the commencement of effective cardiac massage after Patient A's cardiac arrest, prioritizing surgical wound closure and endotracheal intubation.

- (C) Direct Causation with Death Not Established (Traditional Approach): Despite finding these negligent acts, the High Court concluded that it was difficult to establish a direct causal link between these specific breaches of duty and Patient A's death. It reasoned:

- Even if Dr. B had reduced the anesthetic dosages, the precise extent of such reduction would have been within his clinical discretion, and there was no definitive evidence to prove that a specific, appropriate reduction would have certainly prevented the cardiac arrest and death.

- Similarly, there was no conclusive evidence that commencing cardiac massage more promptly would have successfully resuscitated Patient A and averted her death.

- Therefore, the High Court found it challenging to define the "specific content of the duty of care (i.e., the specific negligent act or omission)" that had a direct causal relationship with the fatal outcome.

- (D) "Loss of Chance" of Survival Applied: However, the High Court then applied the "loss of a substantial chance" doctrine. It held that if Dr. B had properly considered dosage adjustments and if resuscitation measures (specifically, cardiac massage) had been initiated more promptly, there was at least a 35% chance that Patient A's death could have been avoided.

- Based on this "loss of chance," the High Court awarded the plaintiffs partial damages, calculated as 35% of what might have been awarded for full liability for death. This amounted to 13 million yen for the loss of life-prolonging potential and 1.3 million yen for legal fees (approximately 34% of the total amount originally claimed).

The plaintiffs, seeking full compensation for Patient A's death, appealed the High Court's decision (specifically, the part that denied full causation and limited damages) to the Supreme Court. The defendant hospital operator (Y) did not appeal the High Court's finding of partial liability based on the "loss of chance."

The Supreme Court's Decision (March 27, 2009)

The Supreme Court overturned the High Court's judgment with respect to the plaintiffs' losing portion (i.e., its denial of full causation for Patient A's death). It found that the High Court erred in concluding that a direct causal link between Dr. B's negligence and Patient A's death could not be established. The case was remanded to the Tokyo High Court for a recalculation of damages based on full liability.

Supreme Court's Reasoning on Negligence:

- The Supreme Court affirmed the High Court's finding that Anesthesiologist B was negligent. It specifically pointed to:

- Patient A's age (65) and small physique (143 cm, 43 kg).

- The package insert for propofol, which indicated that when used with regional anesthetics (like mepivacaine), lower doses are typically sufficient, and caution regarding dose reduction in elderly patients due to increased susceptibility to cardiovascular side effects.

- The package insert for mepivacaine, which also advised considering dose reduction for elderly patients undergoing epidural anesthesia due to their potentially increased sensitivity and narrower therapeutic range. It also listed severe side effects like bradycardia and cardiac arrest.

- The fact that despite these considerations, Dr. B administered a dose of mepivacaine at the upper end of the standard adult range, and maintained a propofol infusion rate consistent with standard adult dosages without apparent adjustment for combination use or Patient A's specific factors.

- Critically, even when Patient A's blood pressure began to fall after the surgery commenced (around 1:55 PM) and did not adequately respond to initial small doses of vasopressors, Dr. B did not reduce the infusion rate of propofol. In fact, the infusion continued at a rate that, for certain periods, exceeded the typical usage examples provided in the propofol package insert for maintaining anesthesia.

The Supreme Court concluded that Dr. B had a clear duty to adjust the dosages of propofol and mepivacaine in light of their combined use and Patient A's individual characteristics.

Supreme Court's Reasoning on Causation with Death – Affirming a Direct Link:

This was the pivotal part of the Supreme Court's decision, differing significantly from the High Court:

- The Supreme Court explicitly stated that it could not uphold the High Court's determination (point C above) that a specific breach of duty causally linked to death was difficult to ascertain.

- The Court then traced the physiological "mechanism" (機序をたどった - kijō o tadotta) of events:

- Dr. B's failure to appropriately adjust anesthetic dosages (negligence).

- This led to Patient A's blood pressure falling to a state where it did not recover with small doses of vasopressors, especially after the surgery began.

- The continued administration of propofol, at times exceeding recommended examples, exacerbated this situation.

- This resulted in a rapid and severe drop in blood pressure, leading to cardiac arrest, and ultimately, Patient A's death.

- The Supreme Court directly concluded: "Dr. B was negligent in failing to adjust the dosages of propofol and mepivacaine as he should have to avoid the outcome of Patient A's death, and it should be said that a considerable causal relationship (相当因果関係 - sōtō inga kankei) exists between this negligence and Patient A's death."

- The Court found no evidence to suggest that Patient A would have died even if the anesthetic dosages had been appropriately adjusted. The fact that the precise "appropriate" reduced dosage might involve some degree of clinical discretion did not negate the finding that the actual dosage regimen administered was negligently excessive and directly led to her death. The High Court's concern that the exact degree of reduction needed to save A was indeterminable was deemed insufficient to negate causation once the administered dose was found to be negligently high and to have caused the death.

Because the Supreme Court affirmed both negligence and a direct causal link to Patient A's death, it remanded the case to the High Court for a recalculation of damages based on full liability for her death, rather than the "loss of chance" approach. (The PDF commentary accompanying this case notes that on remand, a settlement was reached between the parties for the full amount of damages, excluding delay interest, which often happens once the Supreme Court establishes clear liability).

Analysis and Implications: Clarifying Anesthetic Responsibility and Causation

This Supreme Court decision carries significant weight in the realm of medical malpractice, particularly concerning anesthesia-related incidents:

- Reinforced Importance of Package Inserts and Patient-Specific Dosing: The ruling strongly reaffirms the principle that physicians, especially anesthesiologists, must pay close attention to the guidance provided in pharmaceutical package inserts. This includes warnings about combined drug use, dosage adjustments for vulnerable patient populations (such as the elderly or those with small physique), and recommended infusion rates. This case, like the 1996 Percamin S spinal anesthesia case, emphasizes that package inserts are key sources for defining the standard of care.

- Focus on the "Mechanism of Harm" in Causation: The Supreme Court's approach to causation involved identifying a clear physiological pathway or "mechanism" from the negligent act (over-administration of anesthetics) to the adverse outcome (precipitous blood pressure drop, cardiac arrest, death). When such a direct chain of events initiated by the negligent act is established, establishing legal causation becomes more straightforward than in cases where the link is more speculative or involves multiple intervening factors.

- Overcoming Arguments of Clinical Discretion in Clear Overdose Scenarios: While anesthesiology inherently involves clinical judgment and discretion in titrating drug dosages, this decision indicates that such discretion does not provide a shield against liability when the administered dosages are demonstrably excessive in light of established guidelines (package inserts, academic recommendations) and specific patient risk factors, and when this excess directly leads to a recognized adverse drug effect.

- Distinguishing Full Causation from "Loss of Chance": This case serves as an important illustration of how courts differentiate between situations warranting compensation for a "loss of chance" and those where full causation for the ultimate harm (death, in this instance) can be established. Here, the Supreme Court found the anesthesiologist's act of administering excessive anesthesia to be a positive negligent act that directly initiated the fatal sequence of events. This contrasts with scenarios where an omission (e.g., failure to diagnose or a delay in treatment) might only reduce a chance of survival or a better outcome.

- Impact of Defendant's Litigation Stance: As noted in some legal commentaries, the fact that the defendant hospital did not appeal the High Court's initial finding of some negligence (albeit only leading to "loss of chance" damages) might have provided a more conducive background for the Supreme Court to fully affirm negligence and then strengthen the causation finding.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's March 27, 2009, judgment in this fatal anesthesia case provides critical guidance on the responsibilities of anesthesiologists and the legal principles governing causation in medical malpractice. It underscores the imperative to individualize anesthetic drug dosages based on patient characteristics and to strictly adhere to safety information provided in package inserts, especially when using potent drugs in combination. By finding a direct causal link between the negligent over-administration of anesthesia and the patient's death, the Court moved beyond a "loss of chance" framework to affirm full liability, thereby reinforcing the accountability of medical professionals for preventable, drug-induced harm during surgery. This decision serves as a vital precedent for ensuring patient safety in the high-stakes environment of the operating room.