Lessons from a Japanese Conglomerate Delisting: Governance Failures, Activist Battles & Take-Private Exit

TL;DR

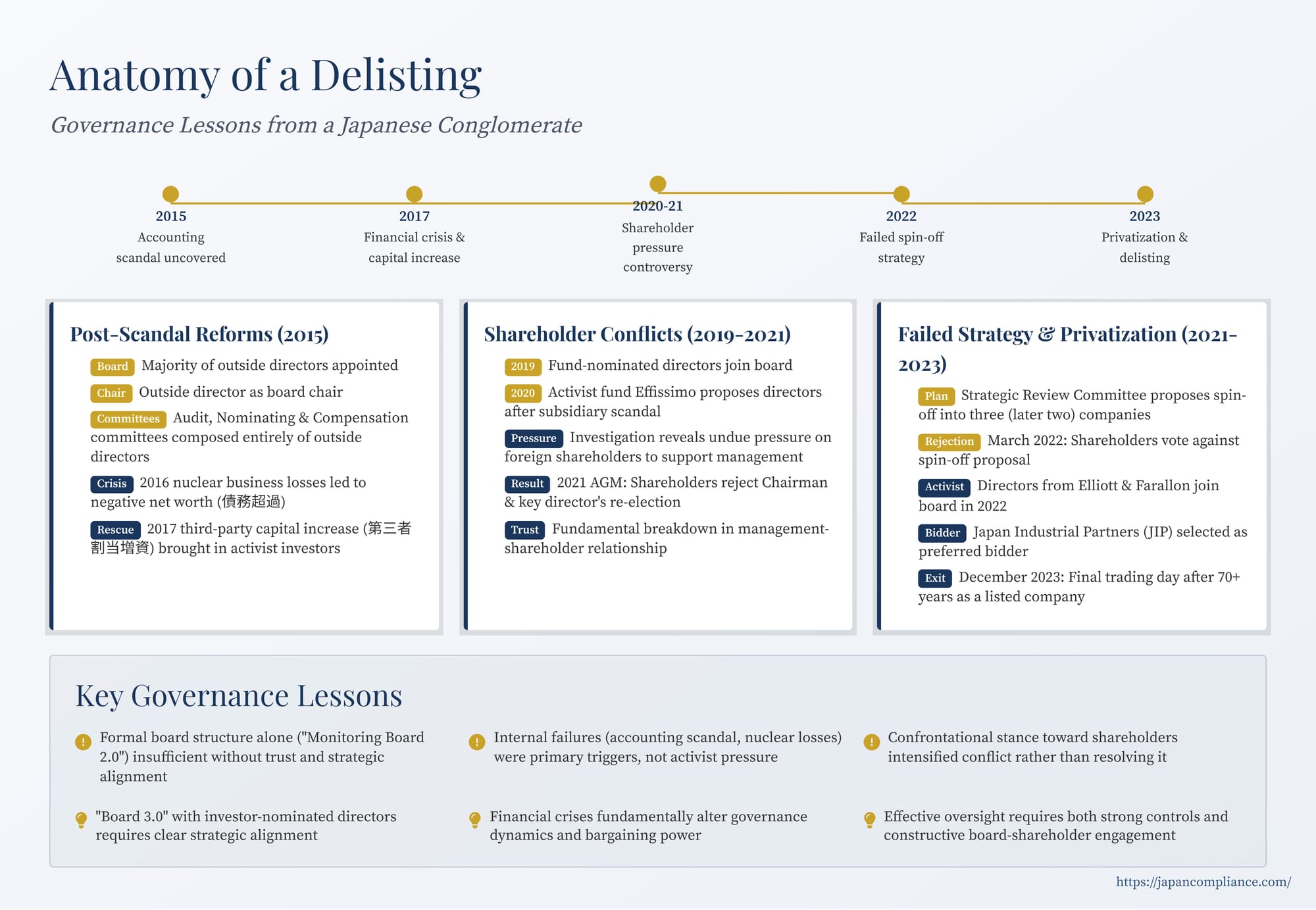

- A seven-decade-old conglomerate left the TSE in Dec 2023 after scandal, insolvency, activist clashes and a take-private buy-out led by JIP.

- “Board 2.0” reforms (outside-director majority) after the 2015 accounting scandal proved inadequate when a 2017 cash crisis brought foreign funds onto the register.

- Prolonged conflict, a failed spin-off vote and regulatory pressure culminated in a tender offer and delisting—highlighting the limits of formal governance fixes.

Table of Contents

- Phase 1: Post-Scandal Reforms and Financial Crisis (2015-2017)

- Phase 2: Shareholder Conflict and Strategic Paralysis (2019-2023)

- Analyzing the Governance Trajectory

- Conclusion

In December 2023, a storied Japanese conglomerate, with a history spanning over seven decades as a publicly listed entity on the Tokyo Stock Exchange, concluded its final day of trading. This departure from the public markets wasn't a typical management buyout (MBO) or a parent company's strategic take-private transaction. Instead, it marked the culmination of nearly a decade of turmoil, beginning with a major accounting scandal and encompassing severe financial distress, strategic missteps, and intense conflict with shareholders. The conglomerate's path to privatization offers critical insights into the challenges of corporate governance reform and shareholder relations in Japan.

Phase 1: Post-Scandal Reforms and Financial Crisis (2015-2017)

The conglomerate's troubles burst into public view in 2015 with the revelation of a massive accounting scandal. Investigations uncovered systemic, long-term inflation of profits across multiple business units, with involvement reaching top management levels. This triggered significant governance reforms.

At an extraordinary shareholders' meeting in September 2015, a new leadership structure was put in place. While retaining the formal "Company with Committees" structure (指名委員会等設置会社, shimei iinkai tō setchi kaisha – Japan's closest equivalent to a US-style board structure with separate audit, nominating, and compensation committees), the board's composition and operation were significantly altered. Key changes included:

- A majority of the board seats were allocated to outside directors.

- An outside director was appointed as board chair.

- The crucial Audit, Nominating, and Compensation committees were composed entirely of outside directors.

- Reflecting the failure of internal controls in the accounting scandal, the Audit Committee was strengthened with financial, legal, and management experts, including a full-time outside director.

On paper, this reformed board appeared well-equipped for robust monitoring (often termed a "Monitoring Board" or "Board 2.0"). However, this newly established structure was almost immediately tested by a severe financial crisis.

In late 2016, devastating news emerged about massive potential losses in the company's US nuclear power business. By 2017, the conglomerate had fallen into negative net worth (債務超過, saimu chōka), leading to its demotion from the prestigious First Section of the Tokyo Stock Exchange to the Second Section in August 2017. More critically, Japanese stock exchange rules mandated delisting if a company remained in negative net worth for two consecutive fiscal years. Management faced an urgent deadline (March 2018) to restore solvency and avoid being forced off the exchange.

The primary rescue plan involved selling the profitable memory chip subsidiary and undertaking a large-scale capital increase (増資, zōshi). While the sale alone might have mathematically resolved the negative net worth, delays in securing regulatory approvals internationally made relying solely on the sale too risky. Consequently, raising new equity capital became unavoidable.

Given the company's precarious financial state and ongoing reporting issues, a domestic public offering was impractical. The only viable option was a large-scale third-party allotment (第三者割当増資, daisansha wariate zōshi) targeting overseas investment funds, which was executed in December 2017. This capital injection successfully averted immediate delisting but fundamentally altered the company's shareholder base, bringing in numerous foreign funds, including activist investors, who would play a pivotal role in the years to come.

Phase 2: Shareholder Conflict and Strategic Paralysis (2019-2023)

While the 2017 fundraising saved the company from delisting, it ushered in a new era of conflict and strategic drift.

Early Signs of Friction: By the 2019 Annual General Meeting (AGM), directors nominated by the newly invested funds (including entities associated with King Street and Farallon) had joined the board. Around the same time, another major Japanese company, Olympus, accepted a director from activist fund ValueAct, a move sometimes cited in discussions of "Board 3.0" – a model where investors contribute directors with specific expertise to enhance strategy. Whether the conglomerate's board resembled this model, however, proved questionable.

The "Pressure Problem": Trouble escalated in 2020. Following the discovery of improper transactions at a subsidiary, activist fund Effissimo proposed its own director candidates at the July 2020 AGM to enhance internal controls. Effissimo's proposals failed, but suspicions arose about the fairness of the AGM process. Compounding the tension, Effissimo, as a major foreign shareholder, faced scrutiny under Japan's recently revised Foreign Exchange and Foreign Trade Act (FEFTA), which tightened regulations on foreign investment in sensitive sectors.

In early 2021, Effissimo successfully petitioned for an extraordinary shareholders' meeting (EGM) to appoint independent investigators to examine the 2020 AGM's proceedings. Just before the June 2021 AGM, the investigators' damning report was released. It detailed alleged efforts by company management, reportedly in concert with officials from Japan's Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI), to unduly pressure foreign shareholders (including Harvard's endowment fund) to align their votes with management or abstain, effectively disenfranchising them. The fallout was immediate: at the 2021 AGM, shareholders voted against the re-election of the Chairman of the Board and another key director.

Governance Enhancement Committee and Strategic Failure: In response to the "pressure problem," the company established a Governance Enhancement Committee. Its report, issued in late 2021, criticized management's handling of the 2020 AGM, deeming it contrary to market ethics even if not strictly illegal. It also pointed to a deeper issue: a perception among executives and Japanese directors that foreign investment funds were inherently adversarial, hindering the building of trust and constructive dialogue.

Simultaneously, a Strategic Review Committee, heavily influenced by the foreign directors nominated by funds, explored options for the company's future. In late 2021, it controversially proposed splitting the conglomerate into three separate companies (later revised to two). This plan faced immediate backlash from several major activist shareholders who favored privatization. The internal divisions were stark, with one activist-nominated director even publicly campaigning against the board-approved plan before a shareholder vote. The spin-off proposal was ultimately rejected by shareholders at an EGM in March 2022.

The Inevitable Delisting: With the spin-off strategy in ruins, the path towards privatization became the dominant focus. A Special Committee was formed in April 2022 to solicit proposals. The June 2022 AGM saw directors linked to activist funds Elliott and Farallon join the board. After a lengthy process, a consortium of Japanese companies led by the private equity fund Japan Industrial Partners (JIP) was selected as the preferred bidder in March 2023. JIP launched a successful tender offer in August 2023, and following a final shareholder vote to consolidate shares in November, the company was formally delisted in December 2023.

Analyzing the Governance Trajectory

Looking back at this complex sequence, two common interpretations warrant scrutiny:

1. Was Activist Short-Termism the Root Cause?

The narrative that short-term oriented activist funds destabilized the company and forced its delisting is an oversimplification. The conglomerate's existential crises stemmed primarily from internal failures predating significant activist involvement: the 2015 accounting scandal and the disastrous US nuclear losses. These events necessitated asset sales (hollowing out the company's growth engines) and the 2017 capital increase, which then brought activists onto the share register. While activists certainly influenced subsequent events, management's confrontational approach and strategic failures (like the ill-fated spin-off) arguably played a larger role in the escalating conflict and eventual decision to go private. The delisting appeared less a result of activist demands and more the endpoint after other recovery strategies failed.

2. Did the Board Evolve to "Board 3.0"?

The idea of "Board 3.0," where engaged investors provide directors with specialized expertise to actively shape strategy, is an appealing concept. Did this conglomerate's board embody it?

- The 2019 Board: While directors nominated by funds joined in 2019, this board subsequently failed basic monitoring duties (a "Board 2.0" failure) during the shareholder pressure scandal and proved incapable of forging consensus around a viable strategy (the failed spin-off). Furthermore, the concept of Board 3.0 generally assumes long-term strategic alignment between the company and the nominating investor. However, at least one major nominating fund engaged in frequent trading of the company's stock after placing its directors, which seems contrary to this premise.

- The 2022 Board: The directors appointed directly from activist funds in 2022 joined when privatization was already the main objective. Their role appeared focused on overseeing the take-private process to ensure shareholder value maximization within that context, rather than co-creating a long-term growth strategy for the public company. This aligns more with shareholders ensuring their interests are represented in a specific transaction, not the broader strategic partnership envisioned by Board 3.0.

Therefore, it's difficult to characterize the conglomerate's board as a successful, or perhaps even genuine, implementation of the Board 3.0 model. If anything, it demonstrated the struggles of even a formally well-structured "Monitoring Board" (Board 2.0) to function effectively under intense pressure and internal division.

Conclusion

The delisting of this iconic Japanese conglomerate was not a simple story of activist pressure forcing a reluctant company private. It was the culmination of deep-seated governance failures, starting with scandal and financial mismanagement, compounded by an inability to strategically rebuild, and exacerbated by a breakdown in relations between management and significant shareholders. The supposedly enhanced governance structure implemented after 2015 proved insufficient to navigate these challenges effectively. This saga serves as a sobering case study on the immense difficulties of turning around a complex organization in crisis and underscores the critical importance of robust internal controls, strategic clarity, and constructive board-shareholder engagement in modern Japanese corporate governance.

- Director Liability and Corporate Donations in Japan: Balancing Philanthropy and Fiduciary Duty

- Shareholder Activism in Japan: The Rise of Derivative Lawsuits and Director Liability

- Mandatory Sustainability Reporting in Japan: FIEA Rules & ISSB Alignment for Global Companies

- FSA Corporate Governance Code – 2021 Revision (PDF)

- METI Report on Group Governance Reforms (Japanese PDF)