An Injection of Air: Japan's Top Court on the Line Between Criminal Attempt and Impossibility

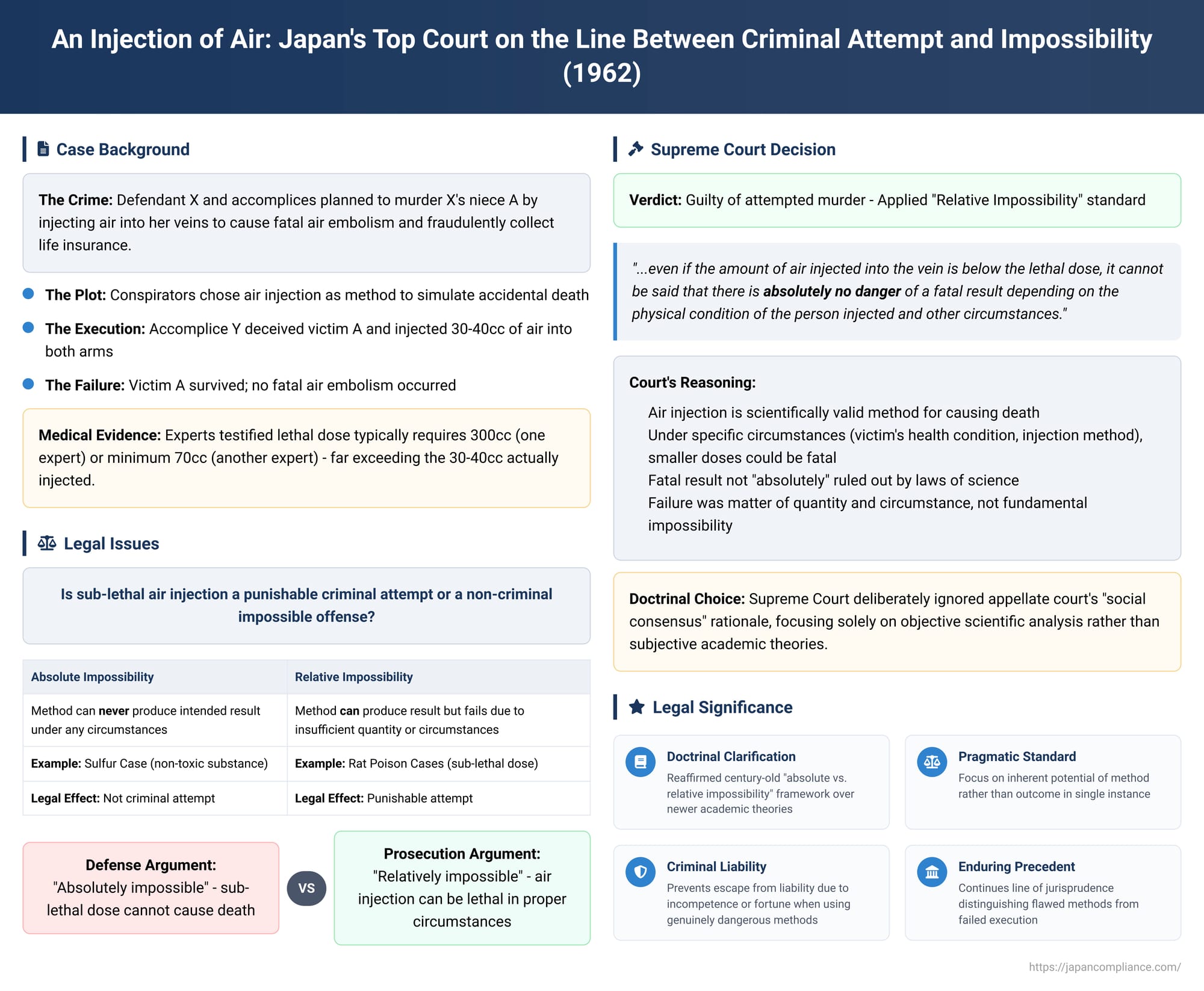

If a person tries to commit murder using a method that seems plausible but ultimately fails because the "dose" was insufficient, have they still committed a crime? Where does the law draw the line between a punishable criminal attempt and a futile, non-criminal act of impossibility? This fundamental question was addressed by the Supreme Court of Japan in a compelling decision on March 23, 1962. The "Air Injection Case," as it has come to be known, provides a crucial window into the Court's long-standing and pragmatic approach to the legal doctrine of "impossible attempts" (不能犯 - funōhan).

The Facts: A Flawed Murder Plot

The case involved a chilling conspiracy. The defendant, X, conspired with several accomplices, including a man named Y, to murder his niece, A, in order to fraudulently collect on her life insurance policy. Their chosen method was to inject air into her veins, hoping to induce a fatal air embolism and make her death appear accidental.

On the day of the crime, the group went to A's location. Y deceived A, convincing her to consent to what she likely believed was a legitimate medical injection. He then proceeded to inject a total of 30 to 40 cubic centimeters (cc) of air into the veins of both of her arms. However, despite their efforts, A did not die.

The Legal Defense: "Absolutely Impossible"

During the trial for attempted murder, the defense put forward a powerful argument based on the doctrine of impossibility. They presented expert medical testimony establishing that the amount of air required to cause a fatal air embolism is typically far greater than what was used. One expert estimated the lethal dose to be around 300cc, while another placed it at a minimum of 70cc.

The defense argued that since the 30-40cc of air injected was scientifically proven to be a sub-lethal dose, it was "absolutely impossible" for their actions to have caused death. Therefore, they contended, their act was not a punishable criminal attempt but a non-criminal impossible offense. They had tried to commit a crime with means that could not possibly succeed.

The Supreme Court's Ruling: The "Relative Impossibility" Standard

The trial court and the appellate court both rejected this defense, and the Supreme Court of Japan ultimately affirmed their guilty verdicts. The Court's reasoning provides a clear illustration of its traditional approach to impossibility.

The justices acknowledged the defense's point about the sub-lethal dosage. However, they focused on a different aspect of the expert testimony. The same experts had also testified that under specific circumstances—such as the victim having a particular health condition (e.g., a heart or lung ailment) or due to the specific method of injection—a smaller-than-average dose of air could potentially be fatal.

Based on this, the Supreme Court endorsed the lower courts' finding that:

"...even if the amount of air injected into the vein is below the lethal dose, it cannot be said that there is absolutely no danger of a fatal result depending on the physical condition of the person injected and other circumstances."

Because a fatal result was not absolutely ruled out by the laws of science, the Court deemed the act to have created a sufficient danger to constitute a punishable attempt. The failure was a matter of circumstance and degree, not of fundamental impossibility. This reasoning is a classic application of the "Relative Impossibility" doctrine.

A Century of Doctrine: The "Sulfur vs. Rat Poison" Distinction

The Supreme Court's decision in the Air Injection Case did not emerge from a vacuum. It was the direct descendant of a line of jurisprudence stretching back to the early 20th century, which distinguishes between two types of impossibility:

- Absolute Impossibility: This applies when the means used can never, under any circumstances, produce the intended result. The foundational precedent is the "Sulfur Case" from the Taisho era (1912-1926), where a woman tried to poison her husband with sulfur. Since sulfur is not chemically toxic to humans, the court ruled the act was "absolutely impossible" and therefore not a criminal attempt.

- Relative Impossibility: This applies when the means used are capable of producing the result, but fail due to some contingent factor, such as an insufficient quantity or an external circumstance. The classic examples are the "Rat Poison Cases," where defendants used real poison but in a sub-lethal dose. In these cases, the courts consistently ruled that the act was a punishable attempt. The reasoning was that rat poison is a deadly substance; the failure was merely a matter of quantity or the victim's fortitude. The act was only "relatively" impossible.

The 1962 Air Injection case fits squarely into this latter category. The act of injecting air into the bloodstream is a scientifically valid method for causing death. It is analogous to using rat poison, not sulfur. The perpetrators' failure was one of quantity and circumstance, not a failure of the method itself.

The Road Not Taken: "Social Consensus" and Other Theories

What makes the Supreme Court's 1962 decision particularly insightful is not just the reasoning it adopted, but also the reasoning it chose to ignore. The appellate court, in its own ruling, had offered a second justification for the conviction: it stated that injecting air into a person's veins is an act that, according to "general social consensus" (shakai tsūnen), is considered dangerous and capable of causing death.

This "social consensus" argument aligns with the prevailing academic theory in Japan, known as the "Concrete Danger Theory" (具体的危険説 - gutaiteki kikensetsu). This theory argues that the test for impossibility should be whether an ordinary person, knowing the facts available at the time, would perceive the act as creating a concrete danger of the crime being completed.

The Supreme Court, however, pointedly omitted any mention of this "social consensus" rationale in its final decision. It based its ruling solely on the traditional, more objective analysis of whether a fatal result was "absolutely" impossible from a scientific standpoint. This deliberate choice signaled the Court's preference for its long-standing "absolute vs. relative" framework over the more subjective academic theories.

Conclusion

The 1962 Air Injection Case remains a crucial pillar in Japanese criminal law, affirming a clear and pragmatic standard for judging impossible attempts. The ruling teaches that the law distinguishes between methods that are fundamentally flawed and methods that simply fail on a particular occasion. If the chosen means is one that, under a different set of circumstances—a larger dose, a more vulnerable victim, a slightly different technique—could have brought about the intended harm, the act is deemed a "relatively impossible" and therefore punishable attempt. The Court's focus is on the inherent potential of the method, not just its outcome in a single instance, ensuring that those who embark on a genuinely dangerous course of criminal action cannot escape liability simply because fortune—or their own incompetence—spared their victim.