Amending Claims in Japan's Supreme Court When a Party Goes Bankrupt: A 1986 Ruling on Judicial Economy

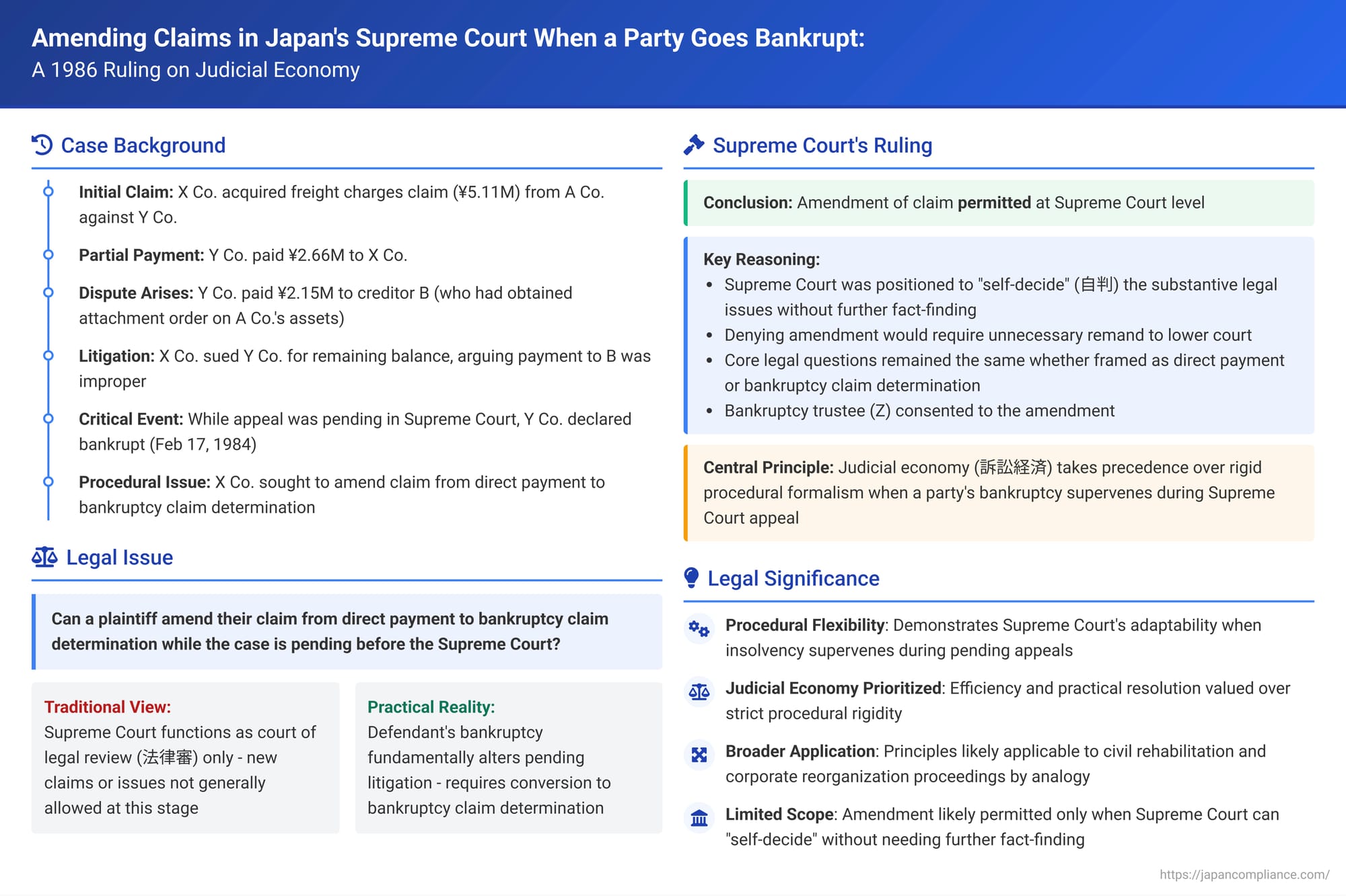

The path of litigation in Japan, as in many legal systems, can be lengthy, often proceeding through a district court, a high court, and potentially culminating in an appeal to the Supreme Court, which primarily reviews questions of law. A unique procedural challenge arises when a party to a lawsuit—specifically, a defendant company—is declared bankrupt while its case is pending before the Supreme Court. If the plaintiff's original monetary claim now needs to be re-characterized as a "bankruptcy claim" to be asserted against the bankrupt defendant's estate, and the bankruptcy trustee disputes this claim, can the plaintiff amend their lawsuit at this late appellate stage? A Supreme Court of Japan decision from April 11, 1986, addressed this procedural conundrum, prioritizing judicial economy in allowing such an amendment.

Factual Background: An Assigned Claim, Disputed Payments, and Bankruptcy During Supreme Court Appeal

The case originated from a dispute over freight charges. X Co. had acquired a claim for freight charges (approximately 5.11 million yen, "the subject claim") from A Co. (the original creditor which had provided transport services) against Y Co. (the debtor). A Co. duly notified Y Co. of this assignment using a document with a certified date, perfecting the assignment against Y Co. and third parties. Subsequently, Y Co. made a partial payment of approximately 2.66 million yen to X Co.

However, another creditor of A Co., an individual named B, later obtained a provisional attachment order and then a final attachment and collection order against a portion of the remaining subject claim (approximately 2.15 million yen) that Y Co. still owed, ostensibly to A Co. These court orders were served on Y Co. Y Co., apparently due to some confusion about whether the original assignment from A Co. to X Co. had been cancelled (there was an erroneous, later retracted, notice of cancellation from A Co.), and under pressure from B's legal representative, paid the attached amount of approximately 2.15 million yen to creditor B.

X Co. then sued Y Co. for the outstanding balance of the subject claim (around 2.44 million yen) plus delay damages, arguing that Y Co.'s payment to B was improper as X Co. was the rightful, perfected assignee of the entire claim. The first instance court partially ruled in favor of X Co. but controversially deducted the amount Y Co. had paid to the attaching creditor B from what Y Co. owed X Co. The High Court dismissed X Co.'s appeal regarding this deduction. X Co. then appealed this point to the Supreme Court, arguing that the lower courts had erred in their application of Civil Code provisions concerning the perfection of claim assignments (Article 467, paragraph 2) and payments made to a quasi-possessor of a claim (Article 478).

The Critical Development: While X Co.'s appeal was pending before the Supreme Court of Japan, a significant event occurred: Y Co., the defendant-appellee, was declared bankrupt on February 17, 1984. Z was appointed as Y Co.'s bankruptcy trustee.

Following Y Co.'s bankruptcy, X Co. filed a proof of its claim (the subject freight charge claim) in Y Co.'s bankruptcy proceedings. Trustee Z, upon reviewing the claim, objected to the portion of X Co.'s claim that corresponded to the amount Y Co. had previously paid to the attaching creditor B (the approximately 2.15 million yen). Trustee Z was then formally substituted into the ongoing Supreme Court litigation as the appellee, representing the bankrupt Y Co.'s estate.

Amendment of Claim in the Supreme Court: Faced with this new procedural posture—where its claim was now a bankruptcy claim disputed by the trustee—X Co. requested permission from the Supreme Court to amend its original claim. Instead of seeking direct payment from Y Co. (which was now bankrupt), X Co. sought to change its prayer for relief to a judgment determining the validity and amount of its bankruptcy claim (破産債権確定の判決を求める訴え - hasan saiken kakutei no hanketsu o motomeru uttae) against Y Co.'s estate for the disputed sum. Trustee Z consented to this proposed amendment.

The Legal Issue: Amendment of Claim from Direct Payment to Bankruptcy Claim Determination at the Supreme Court Level

The primary procedural issue before the Supreme Court was whether such an amendment to the nature of the claim could be permitted at the final appellate stage. Generally, the Supreme Court of Japan functions as a court of legal review (法律審 - hōritsu-shin), meaning it reviews decisions of lower courts for errors of law, but it does not typically re-examine facts or allow new claims or factual issues to be introduced that were not considered by the lower courts. Amendments of claims, particularly those that might necessitate new factual findings, are usually restricted to the fact-finding stages of litigation (i.e., the first instance or high court levels).

However, the bankruptcy of a party fundamentally alters the nature of pending litigation against them concerning monetary claims:

- Under Japanese bankruptcy law (Article 44 of the current Act, similar to Article 69 of the old Act applicable in this case), the commencement of bankruptcy proceedings against a party generally interrupts (suspends) any ongoing lawsuits concerning property that forms part of the bankruptcy estate.

- If the creditor files a proof of claim in the bankruptcy proceedings and that claim is disputed by the bankruptcy trustee (as happened here), the creditor must typically take steps to have their claim judicially determined. If a lawsuit concerning that claim was already pending when bankruptcy commenced, the creditor must "succeed" to that interrupted lawsuit, effectively converting it into a bankruptcy claim determination suit against the objecting trustee (as per Article 127 of the current Act, similar to Article 76 of the old Act).

The question, therefore, was whether this necessary procedural conversion from an ordinary suit for payment to a bankruptcy claim determination suit could properly occur while the case was already before the Supreme Court, or if the case had to be sent back to a lower, fact-finding court for this amendment to be made.

The Supreme Court's Ruling: Amendment Allowed in the Interest of Judicial Economy

The Supreme Court ruled that the amendment of X Co.'s claim was permissible even at the Supreme Court level under these specific circumstances.

The Court's reasoning centered on judicial economy (訴訟経済 - soshō keizai):

- Acknowledgment of the Necessary Transformation of the Suit: The Court first recognized that when a defendant in a pending monetary lawsuit is declared bankrupt, and the subsequently appointed bankruptcy trustee objects to the plaintiff's corresponding filed bankruptcy claim, the lawsuit, if it is to proceed, must effectively be converted into a bankruptcy claim determination suit. This is a statutory consequence of the bankruptcy.

- Efficiency as the Driving Factor: The primary rationale for allowing the amendment at the Supreme Court stage was the efficiency of the judicial process. The Supreme Court noted that if Y Co.'s bankruptcy had not occurred, it (the Supreme Court) would have been in a position to "self-decide" (jihan) the substantive legal issues raised by X Co.'s appeal on their merits—meaning no further fact-finding by a lower court would have been necessary to resolve the core legal dispute about whether Y Co.'s payment to B was wrongful as against X Co.

- Avoiding Unnecessary Remand: Given this, the Court found that it would be contrary to judicial economy and overly formalistic to deny the amendment and remand the entire case to a lower court solely for the purpose of X Co. formally re-characterizing its claim. Such a remand would cause unnecessary delay and expense, especially since the underlying substantive legal questions concerning the validity of X Co.'s claim against Y Co. for the disputed amount remained largely the same, whether framed as a direct payment claim or a bankruptcy claim determination.

- Trustee's Consent: The Court also noted that Z, the bankruptcy trustee, had consented to the amendment, which likely facilitated the Court's pragmatic approach. While trustee consent might not be strictly essential if all other conditions are met, it removed any procedural objection from the opposing side.

- Substance Over Form: In essence, the Supreme Court prioritized the efficient resolution of the underlying substantive legal dispute rather than adhering to a rigid procedural formality that, in this specific supervening insolvency context, would have led to an inefficient outcome.

Having permitted the amendment, the Supreme Court then proceeded to examine the merits of X Co.'s original grounds of appeal (now as applied to its amended request for a bankruptcy claim determination). It found that Y Co.'s payment to the attaching creditor B was indeed improper as against X Co., which was the prior perfected assignee of the claim. Consequently, the Supreme Court self-decided the case, overturning the relevant parts of the lower court judgments and issuing a new judgment confirming X Co.'s bankruptcy claim against Y Co.'s estate for the full disputed amount (approximately 2.6 million yen including certain delay damages).

Significance of the Judgment

This 1986 Supreme Court decision is significant for several reasons:

- Demonstrates Procedural Flexibility in Insolvency Contexts: It illustrates the Supreme Court's willingness to adopt a flexible procedural approach when a party's insolvency supervenes during a pending appeal. It shows that the Court may permit amendments to the nature of a claim to reflect the realities of the insolvency process, provided that such an amendment does not introduce new factual issues that would require a remand to a lower court for fact-finding.

- Prioritizes Judicial Economy: The ruling is a clear example of the Supreme Court placing a high value on judicial economy and the efficient resolution of disputes. When the alternative is an unnecessary procedural delay that does not alter the core legal issues to be decided, the Court may opt for a more pragmatic procedural path.

- Likely Applicability to Other Insolvency Proceedings: The PDF commentary accompanying this case suggests that the principles established here regarding the amendment of a suit at the Supreme Court level due to a defendant's supervening bankruptcy are likely applicable by analogy to similar situations arising in civil rehabilitation and corporate reorganization proceedings. If a defendant enters such proceedings while an appeal is pending, and the Supreme Court is in a position to "self-decide" the main legal issues without further fact-finding, a similar allowance for claim amendment might be expected.

The commentary also briefly touches upon the related but distinct issue of a defendant attempting to file a counterclaim for bankruptcy claim determination in the Supreme Court if the plaintiff goes bankrupt. It notes that a 1968 Supreme Court case disallowed such a counterclaim at the SC level, likely because counterclaims often introduce new factual matters requiring investigation. However, some scholars argue it might be permissible if the Supreme Court could also "self-decide" the counterclaim.

Concluding Thoughts

The Supreme Court's April 11, 1986, decision clarifies an important procedural point: when a defendant in a monetary lawsuit is declared bankrupt while the case is pending appeal in the Supreme Court, and the bankruptcy trustee, after being substituted into the lawsuit, objects to the plaintiff's corresponding bankruptcy claim, the plaintiff may be permitted to amend their original claim for direct payment into a claim for determination of their bankruptcy claim, even at the Supreme Court level. This pragmatic approach is particularly likely if the Supreme Court is in a position to decide the substantive legal issues without needing to remand the case for further factual findings, and if allowing the amendment serves the interests of judicial economy. The ruling reflects a sensible adaptation of appellate procedure to the supervening event of a party's insolvency.