All Shareholders Present, Even by Proxy: When Flawed Meeting Notices Don't Invalidate Resolutions in Japan

Judgment Date: December 20, 1985

Case: Action for Return of Security Deposit (Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench)

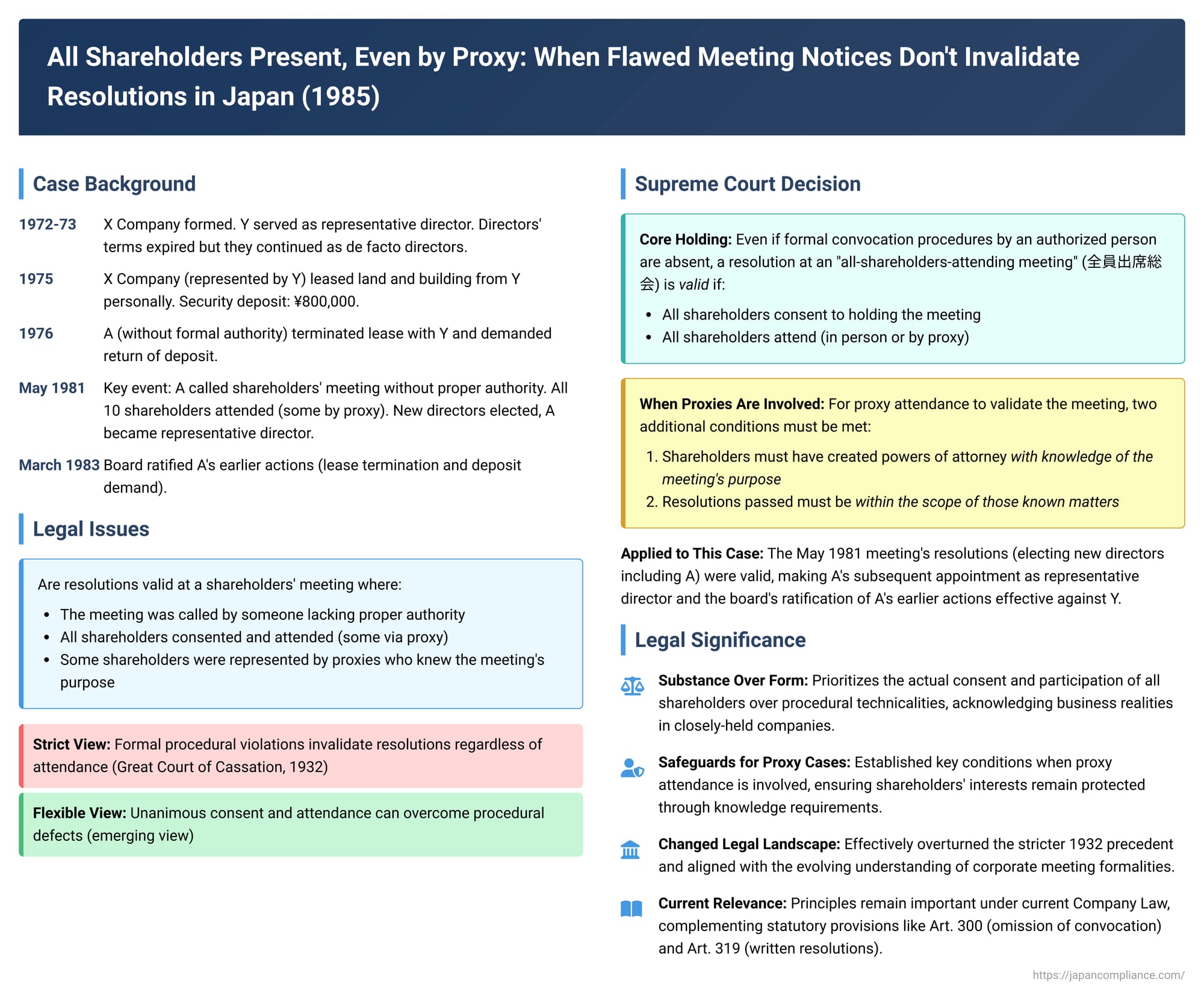

This 1985 Japanese Supreme Court decision addressed a common issue in corporate governance, particularly relevant for smaller, closely-held companies: Can resolutions passed at a shareholders' meeting be considered valid if the formal procedures for convening the meeting were defective, provided that all shareholders attended and consented to the meeting, with some potentially attending via proxy? The Court affirmed the validity of such resolutions under specific conditions, prioritizing substance over strict formality when shareholder consent is unanimous.

Factual Background: A Lease Dispute and an Informally Convened Shareholders' Meeting

The case involved X Company and Y, its former representative director.

- Company Background and Director Issues: X Company was incorporated on February 3, 1972. Y was its representative director, and A, along with four others, served as directors. On February 3, 1973, the terms of all six directors expired. Because new elections were not held, the company fell short of the number of directors required by its articles of incorporation. Consequently, Y, A, and the other former directors continued to operate the company, exercising the rights and duties of their respective positions as de facto directors.

- The Lease and Initial Dispute: In June 1975, X Company entered into a lease agreement with Y (who was still acting as X Company's representative director) for a piece of land and a building. X Company paid Y a security deposit of JPY 800,000. The lease term was for one year. On June 1, 1976, A, despite lacking formal representative authority at that point, purported to act on behalf of X Company and reached a mutual agreement with Y to terminate this lease. A then demanded that Y return the JPY 800,000 security deposit. Y, however, did not comply with this demand. Subsequently, A, again purporting to represent X Company, initiated a lawsuit against Y seeking the return of the security deposit and damages for late payment.

- The Pivotal Shareholders' Meeting (May 31, 1981): While this lawsuit was ongoing in the first instance court, a shareholders' meeting of X Company was held on May 31, 1981.

- This meeting was convened by A for the purpose of electing new directors. It's noteworthy that A, at this specific time, lacked the formal authority to convene such a meeting.

- Despite the potential procedural flaw in convocation, all 10 shareholders of X Company consented to holding the meeting and were considered in attendance. Some of these shareholders attended through proxies they had appointed. These proxies were chosen based on powers of attorney created by shareholders who were aware of the meeting's stated purpose (i.e., the election of directors).

- At this meeting, a resolution was passed electing A and four other individuals (notably excluding Y) as the new directors of X Company.

- Shortly thereafter, this newly elected board of directors convened and passed a resolution appointing A as the new representative director of X Company.

- Ratification of A's Prior Actions: While the lawsuit was pending in the appellate court, on March 19, 1983, the new board of directors (headed by A) passed a resolution to formally ratify A's earlier actions—specifically, the mutual agreement to terminate the lease with Y and the subsequent demand for the return of the security deposit. On March 22, 1983, X Company formally notified Y of this ratification.

- Lower Court Rulings: The first instance court had dismissed X Company's claim. However, X Company appealed, and the High Court reversed the decision, ruling in favor of X Company. The High Court found the 1981 shareholders' meeting resolution to be valid because it qualified as an "all-shareholders-attending meeting" (zen'in shusseki sokai), where all shareholders, including those represented by proxy, were present and consented. Consequently, A's appointment as representative director was deemed valid, and the board's subsequent ratification of A's prior actions regarding the lease termination and deposit demand was effective against Y. Y then appealed this High Court decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Judgment: Consent and Knowledge Uphold Resolution

The Supreme Court dismissed Y's appeal, thereby affirming the High Court's decision in favor of X Company.

The Court's reasoning was as follows:

- Purpose of Formal Convocation Procedures: The Commercial Code (then Article 231 et seq., now largely corresponding to Company Law Article 298 et seq.) mandates formal procedures for convening shareholders' meetings by an authorized person. The legislative intent behind these requirements is to ensure that all shareholders are notified of the meeting's occurrence and its agenda (the "purpose of the meeting"). This provides shareholders with an opportunity to attend and to prepare for participating in the discussions and decisions.

- Validity of "All-Shareholders-Attending Meetings": Based on this understanding of the purpose of convocation rules, the Court held that even if formal convocation procedures by an authorized convener are absent, a resolution passed at a so-called "all-shareholders-attending meeting" is validly established, provided that all shareholders consent to holding the meeting and indeed attend. The Court cited its previous ruling from June 24, 1971 (Minshu Vol. 25, No. 4, p. 596) in support of this principle.

- Validity with Proxy Attendance: Crucially, the Court extended this principle to situations involving proxy attendance. It ruled that if all shareholders are deemed to have attended such an informally convened meeting because proxies appointed based on shareholders' powers of attorney are present, the resolutions passed at that meeting are valid, subject to two conditions:

- The shareholders must have created the powers of attorney with knowledge of the matters to be discussed at the meeting (the "purpose of the meeting").

- The resolutions actually passed at the meeting must be within the scope of those known matters.

Applying these principles to the facts of the case:

- The 1981 shareholders' meeting, although convened by A who lacked formal authority at that moment, saw the attendance of all X Company shareholders (some via proxies). These shareholders had consented to the meeting and, particularly for those appointing proxies, had done so with knowledge of its purpose (the election of new directors).

- Therefore, the resolution passed at this meeting electing A and others as directors was deemed valid.

- As a result, the subsequent resolution by the validly constituted board of directors appointing A as the representative director was also valid. Furthermore, the later board resolution ratifying A's earlier actions concerning the lease termination and the demand for the security deposit's return was likewise valid and effective against Y.

Analysis and Implications: Pragmatism in Corporate Governance

This 1985 Supreme Court decision is significant for its pragmatic approach to shareholder meeting formalities, especially in the context of closely-held companies where operations can often be less formal.

1. The "All-Shareholders-Attending Meeting" (Zen'in Shusseki Sokai) Doctrine:

Japanese company law traditionally emphasizes the importance of proper convocation procedures for shareholders' meetings. These procedures are designed to protect shareholders by giving them adequate notice and the opportunity to prepare for and participate in meetings. Defects in convocation can ordinarily lead to shareholder resolutions being challenged as void or voidable.

However, particularly in smaller, closely-held companies where shareholders often know each other well and may even be involved in management, strict adherence to all formal procedures is not always observed. The concept of the "all-shareholders-attending meeting" addresses this reality. Early 20th-century case law (a Great Court of Cassation ruling from 1932) was very strict, viewing any informally convened gathering, even with all shareholders present, as merely a "meeting of shareholders" whose resolutions were legally void. Some scholars initially supported this strict view.

Over time, the prevailing legal thinking and subsequent case law evolved. The modern understanding, strongly affirmed by this 1985 Supreme Court judgment (and foreshadowed by a 1971 Supreme Court case concerning a one-person company), is that if all shareholders effectively waive the protections afforded by formal convocation procedures by unanimously consenting to hold a meeting and all attending, the resolutions passed at such a meeting can be valid. This 1985 decision is seen as effectively overturning the stricter 1932 precedent.

2. Validity of Proxy Attendance in Such Meetings:

A more debated point was whether this principle extended to situations where full attendance was achieved through proxies. Some legal scholars expressed reservations, concerned that a proxy might not inherently possess the authority to waive procedural rights on behalf of the appointing shareholder.

This 1985 Supreme Court decision was the first by Japan's highest court to explicitly affirm the validity of resolutions passed at an all-shareholders-attending meeting where some shareholders participated via proxy, provided two key conditions were met:

* The shareholders who appointed proxies did so with prior knowledge of the agenda or the purpose of the meeting.

* The resolutions passed at the meeting were confined to the scope of that known agenda.

This "compromise view" gained broad acceptance among legal scholars because it ensures that the shareholder's intent regarding the matters discussed is respected, thereby preventing prejudice to their interests. The PDF commentator even suggests a potentially more expansive interpretation: in certain contexts, particularly for routine matters in small companies, a general proxy might be sufficient if the shareholder’s intent can be reasonably construed, thus validating the meeting.

3. Relevance Under Current Company Law (Post-2005):

The principles from this 1985 judgment remain relevant under Japan's current Company Law, which was significantly reformed in 2005. The current law, in fact, includes provisions that further facilitate procedural flexibility for smaller companies. For instance:

- Companies without a board of directors (取締役会非設置会社 - torishimariyakukai hi-setchi kaisha) have shareholders' meetings that can resolve any matter pertaining to the company (Company Law Art. 295(1)). Their meetings can also decide on matters not explicitly listed in a pre-set agenda (the converse interpretation of Art. 309(5)). In such companies, the convocation notice itself is not even required to specify all agenda items (Company Law Art. 299(4)).

- The question then becomes how the 1985 judgment's conditions (especially regarding knowledge of the agenda for proxies) apply in these more flexible scenarios. The PDF commentator suggests that since shareholders in such companies are aware of this statutory flexibility, a general proxy given by them likely implies broader authorization for the agent to act on typical meeting matters, and resolutions passed at an all-shareholders-attending meeting (including such proxies) should still be considered valid.

Furthermore, the current Company Law has explicitly codified certain mechanisms for procedural simplification when shareholder consent is unanimous:

- Omission of Convocation Procedures: Convocation procedures can be entirely omitted if all shareholders consent (Company Law Art. 300).

- Written/Electronic Resolutions: A shareholders' meeting resolution is deemed to have been passed if all shareholders consent in writing or by electronic means to a proposal, without holding an actual meeting (Company Law Art. 319).

These statutory provisions are distinct from the "all-shareholders-attending meeting" scenario addressed in the 1985 judgment (which still involves a physical or virtual meeting, albeit informally convened). However, they share the common underlying principle of allowing deviations from strict formality when there is unanimous shareholder consent, particularly benefiting smaller and closely-held companies.

Conclusion: Upholding Shareholder Will Amidst Procedural Informality

The 1985 Supreme Court decision striking a balance between procedural regularity and the practical realities of corporate operations, especially in smaller companies. It affirmed that if all shareholders, fully informed and consenting (either personally or through appropriately instructed proxies), participate in a meeting, the resolutions passed can be valid even if the formal steps to convene the meeting were flawed. This ruling emphasizes the importance of unanimous shareholder consent as a powerful curative factor for certain procedural defects, a principle that resonates with several streamlining provisions in Japan's current Company Law.