All In, Then Out: Japan's Supreme Court on Asset Return After Leaving a Communal Living Society (Yamagishikai Case)

Judgment Date: November 5, 2004

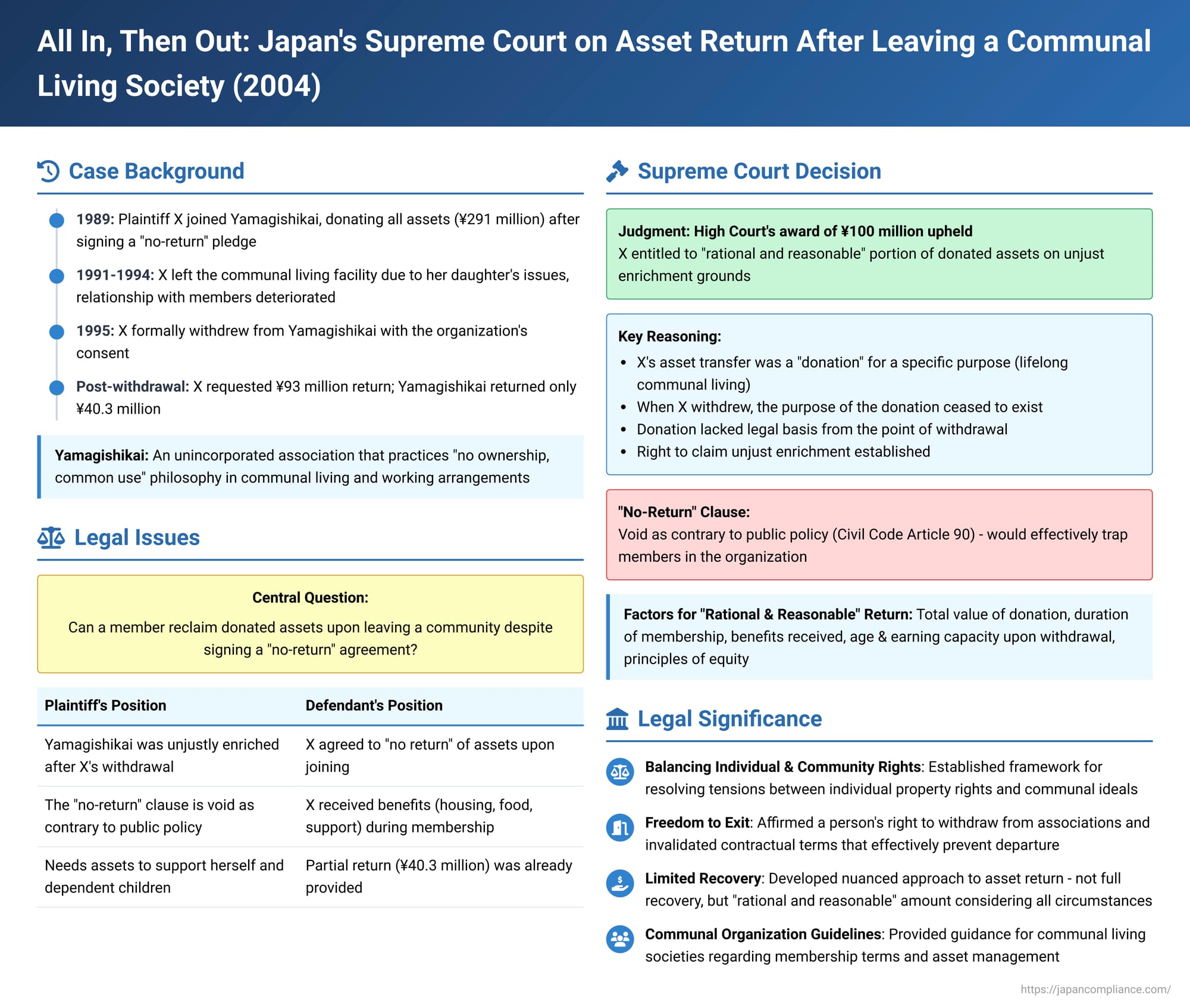

Communal living organizations, often founded on idealistic principles, sometimes require members to donate all their personal assets to the collective upon joining, in exchange for a life where all needs are provided by the community. But what happens when a member, after years of participation and having contributed their entire worldly wealth, decides or needs to leave? Can they reclaim any portion of the assets they donated, especially if they signed an agreement waiving any right to such a return? This complex and deeply human issue was at the heart of a landmark Supreme Court of Japan (Second Petty Bench) decision on November 5, 2004 (Heisei 14 (Ju) No. 808), in a case involving a former member of the Yamagishikai organization.

Yamagishikai: A Society of "No Ownership, Common Use"

The defendant, Y (Yamagishikai), is an unincorporated association (権利能力なき社団 - kenri nōryoku naki shadan) with the stated aim of realizing a "society of no ownership, common use, and integration," referred to as "Yamagishizm Society." Members of Yamagishikai live and work in designated communities known as "Jikkenchi" (実顕地 - literally, "actualization places"). Within these communities, members engage in collective labor, typically in agriculture and related enterprises, and all their living necessities (food, housing, clothing, etc.) are provided by the organization. A core tenet of Yamagishikai is the practice of "no ownership" (無所有 - mushoyū). To this end, individuals wishing to formally join ("participate" - 参画 sankaku) are required to donate all their personal assets—money, property, and possessions—to the Yamagishikai organization.

X's Journey: Joining Yamagishikai and Subsequent Withdrawal

The plaintiff, X, was a woman who, after her husband's death in 1984, was raising three children and living off rental income from an apartment building she owned. In 1989, concerned about her eldest daughter's delinquency, X consulted a local Yamagishikai member. She was subsequently encouraged to attend Yamagishikai's introductory seminars (a 7-night, 8-day "Special Lecture and Study Session" - 特講 tokkō) and further study programs ("Kensan Gakkō").

Inspired by the perceived bright personalities and positive experiences of existing members, and believing that by dedicating herself to what she saw as a sincere way of life she could bring happiness to her children, X decided to join Yamagishikai. On June 15, 1989, she submitted a participation application, a detailed list of her assets for donation, and a pledge. The application documents included statements such as: "I wish to live the Yamagishikai life for my entire lifetime, and therefore will contribute all my human and material assets," and, "I will make no claim for return [of these assets], etc., whatsoever."

Between late June and early July 1989, X handed over all her assets to Yamagishikai, including cash, bank passbooks, pension documents, real estate deeds for her home and apartment building, and her official seal. The total value of these donated assets, including subsequent pension payments received by Yamagishikai on her behalf, amounted to over ¥291 million. X, along with her son and younger daughter, then moved into Yamagishikai's Toyosato Jikkenchi community in Mie Prefecture. (Her eldest daughter's participation was declined by Yamagishikai due to her ongoing behavioral issues).

Several years later, X's circumstances changed significantly. In April 1991, her eldest daughter was placed under probation by a family court, requiring her to live with a guardian. This necessitated X leaving the Jikkenchi community to live with her eldest daughter in an apartment. Her son and younger daughter also subsequently left the Jikkenchi to live with X due to various reasons, including bullying experienced by the son and the younger daughter's enrollment in a Tokyo high school.

Over time, X's relationship with other Yamagishikai members deteriorated, and she began to consider formally withdrawing from the organization. On December 14, 1994, she submitted a request to withdraw, and in early 1995, Yamagishikai consented to her departure. At the time of her withdrawal, X was living with her two dependent, non-earning children (her son and younger daughter).

Upon her withdrawal, X requested Yamagishikai to return at least ¥93 million of her donated assets, primarily for the benefit of her children. However, Yamagishikai only returned ¥40.3 million, designating it as being for her eldest daughter. It was noted that Yamagishikai had covered all living expenses for X and her children during their time in the Jikkenchi, and had also covered X's living expenses in the apartment after she left the community but before her formal withdrawal. After leaving, X supported herself through door-to-door sales of underwear.

The Legal Battle: Unjust Enrichment vs. the "No-Return" Clause

X filed a lawsuit against Yamagishikai seeking the return of the remainder of her donated assets. Her primary claim was based on unjust enrichment (不当利得返還 - futō ritoku henkan), arguing that with her withdrawal, Yamagishikai no longer had a legal basis to retain her assets. She also made a primary claim for damages based on tort, but the unjust enrichment claim became the focus.

The Tokyo High Court, acting as the appellate court, characterized X's asset transfer as a "capital contribution" (出資 - shusshi) to an unincorporated association. While it acknowledged that withdrawal from some types of associations might ordinarily lead to a return of one's share, it also stated that an agreement for a contribution with no right of return is not automatically void. However, the High Court found that the specific "no-return" clause in X's agreement with Yamagishikai was void as contrary to public policy and good morals (Civil Code Article 90). This was because it effectively trapped X by leaving her entirely destitute if she chose to withdraw, thereby severely restricting her freedom. The High Court then granted X's unjust enrichment claim but limited the recoverable amount to ¥100 million. In determining this amount, it considered various factors, including X's understanding when she joined, the value of the assets she donated, the duration of her participation, any benefits she received, her family situation, age, earning capacity, and, significantly, Yamagishikai's overall financial situation. X appealed to the Supreme Court, seeking a larger amount.

The Supreme Court's Framework: Unjust Enrichment Due to "Cessation of Purpose"

The Supreme Court dismissed X's appeal, thereby upholding the High Court's award of ¥100 million as the appropriate amount of restitution. However, the Supreme Court articulated a slightly different, though ultimately compatible, legal reasoning:

- Nature of X's Contribution as a "Donation" for a Specific Purpose: The Court characterized X's transfer of assets not as a "capital contribution" in a commercial or partnership sense, but as a "donation" (出捐 - shutten). This donation was made with the clear understanding and on the explicit premise that X would engage in "lifelong communal living" under Yamagishikai's system and philosophy. The practice of "no ownership" was central to this.

- Withdrawal Nullifies the Purpose of the Donation: X's withdrawal from Yamagishikai, which occurred with Y's consent due to significantly changed personal circumstances, meant that the fundamental purpose or underlying premise of her donation—lifelong communal living—ceased to exist for the future.

- Donation Agreement Loses Its Legal Basis Prospectively: As a result of this cessation of purpose, the Court held that the original agreement under which X donated her assets lost its legal basis and its effect prospectively from the moment of her withdrawal.

- X's Right to Claim Unjust Enrichment: Consequently, X's act of donating her property, from the point of her withdrawal, lacked a continuing legal cause (法律上の原因を欠くに至った - hōritsujō no gen'in o kaku ni itatta). This gave rise to a right for X to claim the return of the donated property (or its value) from Yamagishikai under the principles of unjust enrichment (Civil Code Article 703).

- Scope of Recoverable Unjust Enrichment – A "Rational and Reasonable" Limitation: The Supreme Court agreed with the High Court that X was not entitled to the full return of all assets she had initially donated. The amount recoverable as unjust enrichment must be limited to what is "rational and reasonable" (合理的かつ相当と認められる範囲 - gōriteki katsu sōtō to mitomerareru han'i). This determination requires a comprehensive consideration of various factors, including:

- The total value of the assets donated by X.

- The duration for which X (and her children) lived under Yamagishikai's care and received support.

- The total value of living expenses, provisions, and other benefits X and her family received from Yamagishikai during their period of membership (these benefits received by X are effectively to be deducted from the total value of her donation when calculating the net unjust enrichment to Y).

- X's age and earning capacity at the time of her withdrawal (relevant to assessing her needs and the fairness of the restitution amount).

- Other "various circumstances" and the overarching "principles of equity" (条理 - jōri).

(Notably, the Supreme Court did not explicitly include Yamagishikai's overall financial situation as a factor in this list, unlike the High Court, possibly to keep the reasoning more strictly aligned with unjust enrichment principles which focus on the enrichment of the defendant at the plaintiff's expense, rather than broader considerations of equitable distribution based on the defendant's ability to pay.)

- The "No-Return" Clause – Void Against Public Policy: The Supreme Court affirmed that the clause in the participation agreement stating X would make no claim whatsoever for the return of her donated assets was void as contrary to public policy and good morals (Civil Code Article 90), specifically to the extent that it would prevent X from recovering the "rational and reasonable" portion of her assets as determined above. The Court reasoned that such a clause, by stripping a withdrawing member of all assets they had contributed and leaving them with no means to support themselves outside the community, effectively coerces members into remaining with the organization against their will and constitutes an undue restriction on their freedom to withdraw from the association.

- Affirmation of the High Court's Award Amount: The Supreme Court concluded that the High Court's determination that ¥100 million was the "rational and reasonable" amount for Yamagishikai to return to X was justifiable based on these principles and the specific facts of the case.

Analyzing the Decision: Balancing Individual Rights and Communal Ideals

The Supreme Court's decision in the Yamagishikai case navigated a delicate balance between respecting an individual's right to their property and freedom of association (including the freedom to leave an association), and the unique nature of communal organizations that operate on principles distinct from mainstream society.

- Circumventing Traditional Unincorporated Association Law: By characterizing X's contribution as a "donation" for a specific (now ceased) purpose, rather than as a "capital investment" or "membership share" in an unincorporated association, the Supreme Court managed to sidestep some older precedents. These precedents often held that members withdrawing from unincorporated associations generally have no right to a return of their contributions or a distribution of collective assets, as such associations are typically considered to hold property collectively, without individual member shares. The "donation with a failed purpose" framework provided a more direct route to restitution in this specific context.

- Focus on "Cessation of Purpose" for Unjust Enrichment: The legal basis for the unjust enrichment claim here is not a flaw in the initial contract or donation, but the subsequent event of X's withdrawal, which caused the fundamental purpose of the lifelong donation to cease. This is a recognized category of unjust enrichment where a benefit, initially given for a valid reason, later loses its legal justification.

- Equitable Considerations in Unjust Enrichment: The multi-factor test laid out by the Supreme Court for determining the "rational and reasonable" scope of return introduces significant equitable considerations. It ensures that while the withdrawing member is not left destitute, the organization is also not unfairly burdened by having to return the full value of assets after having provided for the member's living expenses and other benefits over a substantial period. This approach bears some resemblance to principles used in dividing assets upon the dissolution of other long-term communal relationships, such as marital property division.

- Upholding Freedom of Withdrawal: The Court's firm stance in voiding the "no-return" clause as contrary to public policy is a strong affirmation of an individual's freedom to leave an association or communal living arrangement, particularly when such a clause would, due to the complete surrender of personal assets upon entry, make withdrawal practically impossible and thus illusory.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 2004 decision in the Yamagishikai case established an important precedent for situations where individuals donate all their assets to join communal living organizations based on an expectation of lifelong participation. The Court affirmed that if a member later withdraws due to changed circumstances (and with the organization's consent), the initial purpose of the asset donation ceases, giving rise to a claim for unjust enrichment. However, the amount recoverable is not the full value of the donated assets but is limited to a "rational and reasonable" sum, determined by balancing the value of the donation against the benefits received by the member during their time with the organization and considering their circumstances upon departure. Crucially, any contractual clause that purports to completely bar the return of such assets under these circumstances, thereby severely restricting a member's freedom to leave, is deemed void as contrary to public policy. This ruling carefully navigates the intersection of individual property rights, freedom of association, and the unique operational principles of communal societies.