Alighting From a Vehicle: A 2016 Japanese Supreme Court Look at When an Injury "Arises From Its Operation" for Insurance Purposes

Judgment Date: March 4, 2016

Court: Supreme Court, Second Petty Bench

Case Name: Insurance Claim Main Suit, Unjust Enrichment Counterclaim

Case Number: Heisei 27 (Ju) No. 1384 of 2015

Introduction: The Fine Line of "Operation-Causation" in Passenger Injury Insurance

Passenger Injury Insurance (搭乗者傷害保険 - tōjōsha shōgai hoken) is a common feature in automobile insurance policies in Japan. It provides crucial financial benefits to individuals who sustain injuries, suffer disabilities, or die as a result of accidents while they are passengers in an insured vehicle. A key trigger for this coverage, however, is that the injury or death must "arise from the operation" (運行に起因する - unkō ni kiin suru) of that vehicle.

This concept of "operation-causation" (運行起因性 - unkō kigensei) can often be straightforward when an injury results directly from a collision or the vehicle's movement. But what about incidents that occur during the process of boarding or, as in a significant 2016 Japanese Supreme Court case, alighting from a stationary vehicle? If an elderly, frail passenger is injured while being assisted off a vehicle, particularly if a customary safety aid like a footstool is not used by the assistant, can this injury still be considered to have "arisen from the vehicle's operation"? Or does the cause shift to the nature of the assistance itself, or other external factors, thereby taking it outside the scope of passenger injury coverage? This nuanced question was at the heart of the 2016 Supreme Court decision.

The Facts: A Frail Passenger, A Missing Footstool, and an Injury Upon Alighting

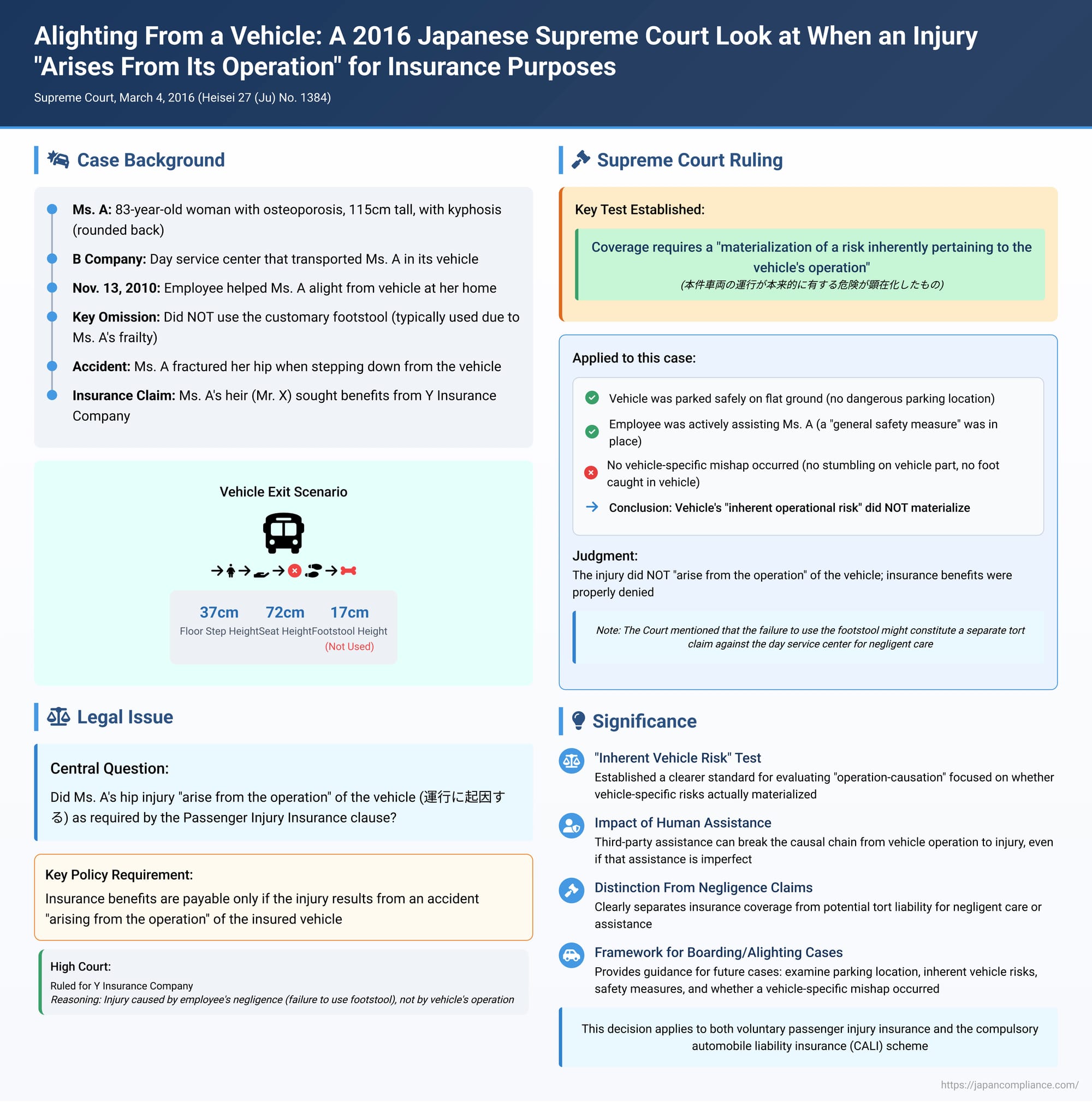

The case involved Ms. A, an 83-year-old woman with several frailty factors, including osteoporosis, a height of approximately 115 cm (about 3 feet 9 inches), and kyphosis (a rounded back). Ms. A was a user of a day service center operated by B Company. As part of its services, B Company provided transportation for Ms. A to and from the center using its own vehicle (referred to as "the subject vehicle"). This vehicle had a relatively high floor step, about 37 cm (approx. 14.5 inches) from the ground, and the rear seat surface was about 72 cm (approx. 28 inches) from the ground.

Given Ms. A's physical condition, it was the usual practice for staff from the day service center to assist her when she was alighting from the vehicle. This assistance typically included placing a footstool, approximately 17 cm (about 6.7 inches) high, on the ground below the vehicle's step to reduce the height she needed to negotiate.

On November 13, 2010, Ms. A was being transported home from the day service center in the subject vehicle. The vehicle was parked on a flat, safe area of ground in front of her residence. The day service center employee responsible for her transport on that day assisted Ms. A in alighting. However, on this particular occasion, the employee did not use the customary footstool. Instead, the employee took Ms. A's hand and guided her as she stepped directly from the vehicle's floor step down to the asphalt ground. Tragically, as Ms. A landed on the ground, she suffered a serious injury: a fracture of her right femoral neck (a broken hip). This incident was referred to as "the subject accident."

B Company, the operator of the day service center, had an automobile insurance policy for the subject vehicle with Y Company. This policy included a Passenger Injury Insurance special rider. The rider stipulated that insurance benefits would be paid if a passenger in the vehicle sustained bodily injury (leading to medical treatment, hospitalization, residual disability, or death) as a result of an accident "arising from the operation" of the vehicle.

Following the accident, Ms. A (and subsequently, after her death from unrelated causes, her child and heir, Mr. X) claimed benefits under this Passenger Injury Insurance rider from Y Company. Y Company initially paid some medical and hospitalization benefits but later disputed further liability, particularly for residual disability benefits. Y Company also filed a counterclaim against Mr. X, seeking the return of the benefits already paid, arguing that Ms. A's injury did not, in fact, "arise from the operation" of the vehicle.

The Core Legal Question: Did Ms. A's Injury "Arise From the Operation" of the Vehicle?

The central legal issue for the courts was whether Ms. A's injury, sustained while she was stepping down from the stationary vehicle with assistance but without the usual footstool, met the crucial policy requirement of "arising from the operation" of the vehicle.

- When does an injury that occurs during the process of alighting from a vehicle, especially when influenced by human assistance (or alleged shortcomings in that assistance), cross the threshold to be considered legally caused by the "vehicle's operation"?

- How does the omission of a customary safety aid, like a footstool, by an assisting third party affect the causal link between the vehicle's inherent characteristics (e.g., its step height) and the injury?

The Lower Court Ruling (High Court)

The Fukuoka High Court (the "original judgment" referred to by the Supreme Court) had ruled against the claimant, Mr. X. It found that Ms. A's accident was primarily caused by the negligence of the day service center employee, specifically the failure to use the footstool and the failure to ensure Ms. A could land safely. The High Court concluded that there was no legally adequate causal relationship between the vehicle's operation and the accident. In its view, the injury was not a result of a risk materializing from the vehicle itself, but rather from an issue of improper care provided during the disembarkation process.

Mr. X then sought a final appeal to the Supreme Court of Japan.

The Supreme Court's Decision (March 4, 2016): Focusing on the "Materialization of an Inherent Vehicle Risk"

The Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench, dismissed Mr. X's appeal. It upheld the High Court's ultimate conclusion that Y Company was not liable under the Passenger Injury Insurance rider, but it did so by applying a more refined legal reasoning centered on a specific test for "operation-causation."

The Key Criterion: "Materialization of a Risk Inherently Pertaining to the Vehicle's Operation"

The Supreme Court articulated or, at least, prominently applied, a key criterion for determining whether an accident "arises from the operation" of a vehicle. It stated that for coverage to be triggered, the accident must be a "materialization of a risk inherently pertaining to the vehicle's operation" (本件車両の運行が本来的に有する危険が顕在化したもの - honken sharyō no unkō ga honrai-teki ni yūsuru kiken ga kenzaika shita mono).

Application of this Criterion to the Specific Facts of Ms. A's Accident

The Supreme Court then applied this criterion to the circumstances of Ms. A's injury:

- No Dangerous Parking Location: The Court first noted that there was no evidence or allegation that the day service center employee had parked the subject vehicle in an unusually dangerous or hazardous location that might have contributed to the risk of falling during disembarkation (e.g., the vehicle was not parked on a steep slope, on uneven or slippery ground, or too close to an obstacle). This factor, if it had been present, might have pointed towards a risk directly related to the vehicle's operation (i.e., improper positioning for safe egress).

- "General Safety Measures" Were Considered to Have Been Taken (Despite the Missing Footstool): The Supreme Court observed that Ms. A was being actively assisted by the day service center employee while she was disembarking from the vehicle. Crucially, the Court characterized this human assistance as a "general measure taken to prevent the vehicle's inherent risks from materializing." Even though a specific customary measure (the footstool) was omitted, the presence of direct human assistance during the alighting process was seen as a form of safety management.

- No Specific Vehicle-Related Mishap Occurred During the Landing Phase: Most importantly, the Supreme Court found that as a result of this human assistance (even in the absence of the footstool), Ms. A did not experience a mishap that could be directly and specifically attributed to the vehicle's own characteristics or a failure of its equipment during the landing phase. For example, the Court noted there was no evidence that she had stumbled over a part of the vehicle itself, that her foot had become caught in or on the vehicle, that she had tripped on the vehicle's step due to its condition, that her ankle had been twisted due to an awkward angle necessitated by the step, or that she had suffered an "unexpectedly strong impact" on her legs or hips that could be directly ascribed to the vehicle's height or structure in the context of a mismanaged landing that was still tied to a vehicle-based hazard.

- Conclusion: The Vehicle's "Inherent Operational Risk" Did Not Materialize: Given these specific findings – particularly the presence of human assistance which the Court viewed as a general safety measure aimed at mitigating vehicle-related risks, and the absence of any specific vehicle-related event causing the fall – the Supreme Court concluded that Ms. A's injury, while it certainly occurred during the process of disembarking from the vehicle, was not a materialization of a risk that inherently pertains to the vehicle's operation itself. The chain of causation linking the "vehicle's operation" to Ms. A's injury was deemed to have been broken or, at least, was insufficient. The Court found that the direct cause of the injury was more closely related to the manner in which the assisted landing onto the ground occurred, separate from a risk that emanated directly from the vehicle as a mode of transport or from its specific equipment or structural characteristics manifesting as a hazard in that moment.

Therefore, the Supreme Court held that Ms. A's accident did not "arise from the operation" of the vehicle within the meaning of the Passenger Injury Insurance rider, and Y Company was not liable to pay the insurance benefits.

Acknowledging a Separate Issue of Potential Caregiver Negligence

The Supreme Court did, however, make an important aside. It noted that the failure of the day service center employee to use the footstool, especially given Ms. A's known frailty and the established usual practice of using it for her, might well constitute a breach of a duty of care owed by the day service center (or its employee) to Ms. A. This could potentially give rise to a separate tort claim by Ms. A (or her estate) against the day service center or the employee for negligence in providing care during the disembarkation process. However, the Court emphasized that this was a different legal question from whether Ms. A's injury was covered by the vehicle's Passenger Injury Insurance based on the specific policy requirement of "operation-causation."

Analysis and Broader Implications of the Ruling

This 2016 Supreme Court decision is significant for its articulation and application of the "materialization of an inherent vehicle risk" test in determining "operation-causation" for passenger injury claims, particularly in the often-litigated context of injuries sustained during boarding or alighting.

1. The "Materialization of Inherent Vehicle Risk" Test as a Key Criterion:

The judgment's prominent use of this test provides a more specific analytical framework than simply looking for "adequate causation" in the abstract. It directs attention to whether a risk that is specific to the vehicle itself and its normal operation (including risks associated with its design and equipment for passenger ingress and egress) actually manifested and was a direct cause of the injury.

2. Contextualizing "Operation-Causation" in Japanese Insurance Law:

As legal commentary (such as the PDF provided with this case) explains, the phrase "arising from operation" as used in voluntary automobile insurance policies (like the Passenger Injury Insurance rider here) is generally interpreted by courts and scholars in Japan to be synonymous with the phrase "by reason of operation" (運行によって - unkō ni yotte) found in Article 3 of Japan's Compulsory Automobile Liability Insurance (CALI) Act. Therefore, this Supreme Court ruling, while dealing with a voluntary insurance policy, can also provide important guidance for interpreting the scope of "operation-causation" under the compulsory CALI scheme.

The commentary further details a long and complex history of legal debate in Japan concerning the precise definition of "operation" (e.g., whether it is limited to the vehicle's engine-driven movement, or includes the use of other driving-related devices, or extends more broadly to the use of any "inherent device" of the vehicle, such as doors, steps, or even specialized equipment like cranes on commercial vehicles) and the nature of the causal link required by the phrase "by reason of." The "inherent risk materialization theory" (固有危険性具体化説 - koyū kikensei gutaika setsu), with which this 2016 Supreme Court judgment appears to align, has become an influential approach. This theory posits that "operation" involves using a vehicle's inherent devices (which embody its specific, characteristic risks) in their intended manner, such that those risks become potentially manifest, and "causation" is established if such a materialized vehicle-specific risk leads directly to an injury.

3. The Impact of Third-Party Assistance or Intervention on the Causal Chain:

A particularly noteworthy aspect of this ruling is the significant weight the Supreme Court gave to the "general measures" that were taken to prevent vehicle-related risk from materializing – specifically, the human assistance provided by the day service center employee to Ms. A during her disembarkation. Even though a specific and customary safety measure (the footstool) was omitted in this instance, the Court viewed the presence of general human assistance as a factor that effectively managed or mitigated the vehicle's inherent risks (such as the risk posed by the height of the step). Because this assistance was in place, and because no specific vehicle-related mishap (like a stumble on the step itself, a trip caused by a vehicle part, or an injury from an unexpected vehicle movement) was found to have occurred during the landing process, the Court concluded that the vehicle's inherent risk did not actually materialize as the cause of the injury. This suggests that intervening human actions, if they provide a general layer of safety management around the process of interacting with the vehicle, can be seen as breaking or superseding the causal chain from "vehicle operation" to an injury, even if those human actions might themselves be imperfect or give rise to a separate claim of negligence against the assistant.

4. Objective Assessment of "Vehicle Risk" Versus Consideration of Passenger Frailty:

Legal commentary points out that the Supreme Court, in its analysis, did not appear to factor in Ms. A's specific individual frailties (her advanced age, osteoporosis, small stature, or rounded back) when it was defining or assessing the "vehicle's inherent risk." The risk associated with the vehicle (e.g., the hazard posed by a certain step height) seemed to be assessed more objectively, as a general characteristic of the vehicle. The focus of the "operation-causation" inquiry was on whether that vehicle-specific risk materialized and directly caused the injury, not on whether the specific level of assistance provided was perfectly tailored to Ms. A's unique vulnerabilities (an issue that would be more directly relevant to a potential tort claim against the caregiver or the day service center for negligence in their duty of care).

5. Distinguishing Insurance Coverage from Potential Tort Liability for Negligent Care:

The Supreme Court was careful to draw a distinction between the question of insurance coverage under the vehicle's Passenger Injury Insurance rider (which depends on "operation-causation") and any potential separate tort liability that the day service center or its employee might face for negligence in the manner they assisted Ms. A (e.g., by failing to use the footstool). The latter would depend on different legal standards, such as proving a breach of a duty of care and causation leading to foreseeable harm. An injury occurring during an activity related to a vehicle does not automatically mean it arises from the vehicle's operation for insurance purposes if the more direct and proximate cause is found elsewhere.

6. Guidance for Future Cases Involving Injuries During Boarding or Alighting:

This Supreme Court ruling provides a more refined analytical framework for assessing injuries that occur while passengers are getting into or out of vehicles. Future cases involving such scenarios will likely require a careful examination of several factors:

- Was the vehicle parked in a location that was itself hazardous for boarding or alighting, thereby creating an operation-related risk (e.g., on a steep incline, on an unstable surface, too far from a curb)?

- What are the inherent risks associated with the vehicle's specific structure that are relevant to the process of boarding or alighting (e.g., the height of its steps, the design of its doors or handles, any known mechanical issues with these components)?

- Were general safety measures in place, or being actively employed, to manage or mitigate these vehicle-specific risks at the time of the incident?

- Crucially, did a vehicle-specific risk (such as a defect in a door mechanism causing it to behave unexpectedly, a passenger slipping on a vehicle step due to its condition, an injury caused by an unintended movement of the stationary vehicle, or a fall directly attributable to the vehicle's height or design during the act of stepping) actually materialize and serve as the direct and proximate cause of the injury? Or was the injury more directly attributable to other factors, such as a simple misstep by the passenger on the ground once they were substantially clear of the vehicle's direct operational influence, or to the manner of assistance provided by a third party, rather than to a risk emanating from the vehicle itself?

Conclusion

The March 4, 2016, decision by the Supreme Court of Japan offers significant clarification on the crucial concept of "operation-causation" within the context of Passenger Injury Insurance claims. It establishes that for an injury sustained by a passenger, particularly during the process of disembarking from a vehicle, to be covered under such a policy as "arising from the operation" of the vehicle, the injury must be shown to be a materialization of a risk that inherently pertains to the vehicle's operation itself.

In the specific circumstances of this case – where an elderly and frail passenger was injured while being assisted by a caregiver in stepping down from a day service vehicle, but without the use of a customary footstool – the Supreme Court found that because general human assistance was being provided (which the Court viewed as a measure intended to prevent vehicle-related risks from manifesting), and because no specific vehicle-related mishap (such as a stumble on the vehicle's step or an unexpected impact directly attributable to the vehicle's height or structure) occurred during the actual landing process, the vehicle's inherent operational risk was not deemed to have materialized as the cause of the injury. Consequently, the injury was held not to have arisen from the vehicle's operation for the purposes of triggering coverage under the Passenger Injury Insurance rider.

This judgment introduces a more refined and specific test for assessing "operation-causation." It underscores that while the vehicle's characteristics (like step height) can constitute an inherent risk, the presence of intervening safety measures (such as human assistance) can be seen as preventing that specific vehicle risk from materializing, even if those measures are imperfect in other respects. The ruling carefully distinguishes such insurance coverage questions from potential separate claims in tort that might arise from alleged negligence in the provision of care or assistance during the disembarkation process itself.