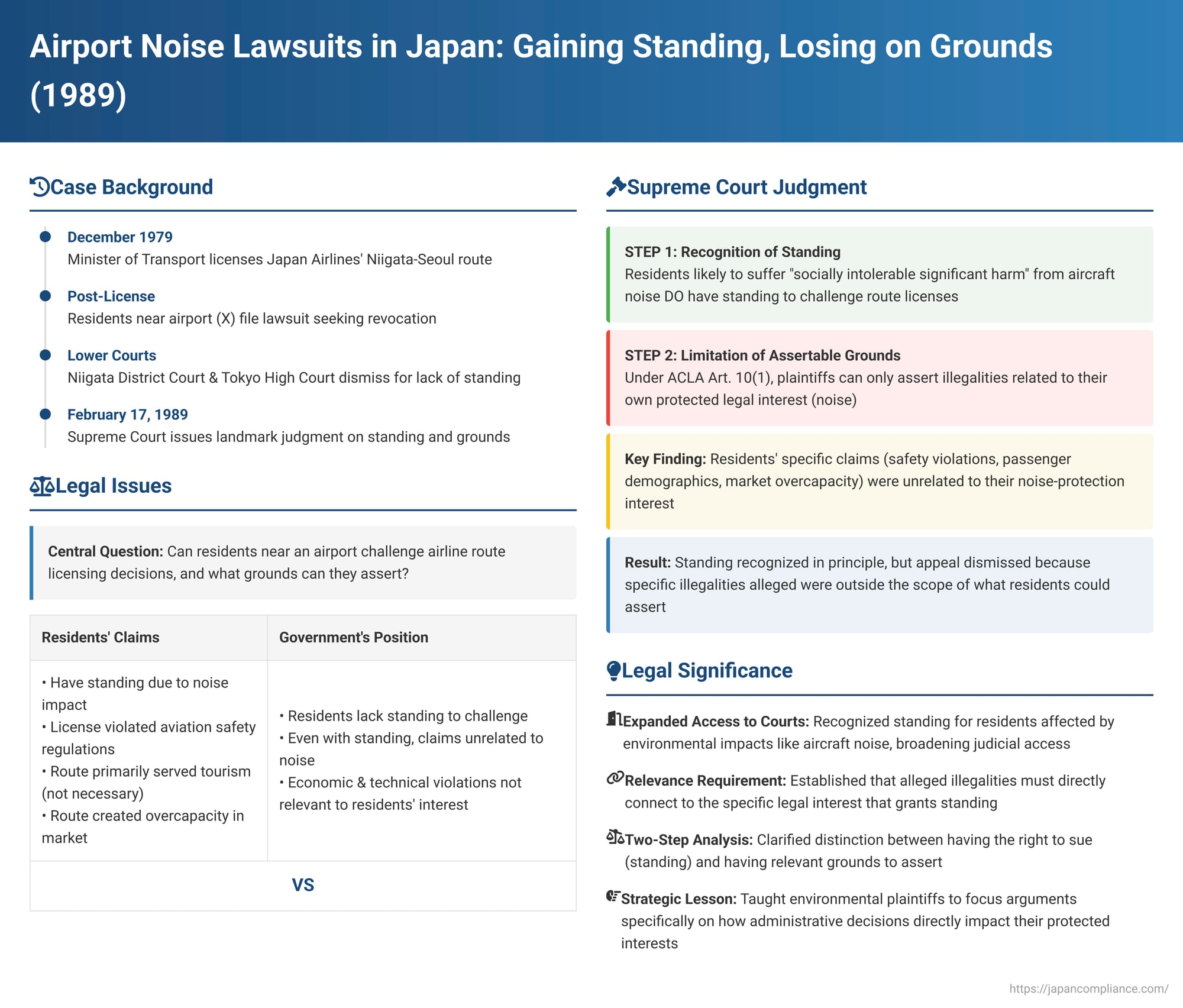

Airport Noise Lawsuits in Japan: Gaining Standing, Losing on Grounds

Judgment Date: February 17, 1989

Case Number: Showa 57 (Gyo-Tsu) No. 46 – Claim for Revocation of Regular Air Transport Business License (Niigata-Komatsu-Seoul Route)

When a new airline route is licensed, residents living near the affected airport often raise concerns about increased noise. A 1989 Japanese Supreme Court decision addressed a critical lawsuit brought by such residents, offering a landmark ruling on their right to sue (plaintiff standing) but also delivering a crucial lesson on the types of arguments they can successfully make in court. The case highlights a two-step inquiry: first, whether a person has the legal right to be in court at all, and second, whether the specific illegalities they allege are relevant to that right.

The Niigata-Seoul Route Dispute

In December 1979, the Minister of Transport (the Defendant, "Y") granted Japan Airlines a license for a regular air transport route connecting Niigata and Seoul. Residents living near the airport (represented by X) filed a lawsuit seeking the revocation of this license. They claimed that the operation of the new route would lead to increased aircraft noise, thereby infringing upon their health and fundamental living interests.

The lower courts—the Niigata District Court and the Tokyo High Court—both dismissed the residents' lawsuit at the threshold, ruling that residents living near an airport do not have the necessary "plaintiff standing" (原告適格 - genkoku tekikaku) to legally challenge an airline route licensing decision. X appealed this determination to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Two-Step Analysis (February 17, 1989)

The Supreme Court, in its judgment, undertook a two-part analysis that ultimately led to the dismissal of X's appeal, but for reasons significantly different from those of the lower courts.

Part 1: Who Can Sue? Establishing Plaintiff Standing for Airport Noise

The first, and perhaps most groundbreaking, part of the judgment dealt with plaintiff standing. The Court established a framework for recognizing when residents affected by aircraft noise do have the legal right to challenge an airline route license:

- "Legally Protected Interest": The Court reiterated its established test for determining who is a "person having a legal interest" to sue under Article 9 of the Administrative Case Litigation Act (ACLA). This includes individuals whose rights or legally protected interests are infringed or inevitably threatened by an administrative disposition. Such protection exists if the relevant administrative laws, considered as a whole system, intend not merely to absorb individual interests into the general public good but also to protect those interests as belonging to specific individuals.

- Aviation Law System and Noise: The Court examined the Aviation Act and related laws concerning the regulation of regular air transport services. It found that the licensing standard in Article 101, Paragraph 1, Item 3 of the Aviation Act—requiring a business plan to be "appropriate for management and aviation safety"—must be interpreted to include consideration of the potential noise disturbance caused by the proposed air traffic in areas surrounding the airports to be used.

- Individual Protection from Noise: Given the specific nature of aircraft noise (its impact is geographically limited to areas around airports and intensifies closer to flight paths), the Court concluded that the Aviation Act's framework for considering noise impact aims not only to protect general public environmental interests but also to safeguard the individual interests of nearby residents from suffering "significant harm" (著しい障害 - ichijirushii shōgai).

- Standing Granted for "Socially Intolerable Significant Harm": Therefore, the Supreme Court held that residents living near an airport used for a newly licensed route, who are likely to suffer "socially intolerable significant harm" (社会通念上著しい障害 - shakai tsūnenjō ichijirushii shōgai) from aircraft noise due to factors such as noise levels, flight frequency, and operational times, do indeed possess plaintiff standing to seek the revocation of that license.

This part of the ruling was a significant development, as it recognized, in principle, the right of residents to sue over noise from new airline routes, overturning the lower courts' blanket denial of standing. The Court stated the lower courts erred by dismissing the suit without examining the extent of potential noise harm to X.

Part 2: What Can They Argue? The Catch of ACLA Article 10(1)

Despite this principled recognition of potential standing, the Supreme Court then turned to the specific grounds of illegality that X had actually argued in their lawsuit. This brought Article 10, Paragraph 1 of the ACLA into play. This provision states: "In a suit for the revocation of an original administrative disposition or administrative disposition on appeal, it is not permitted to request revocation on the grounds of an illegality which is not related to the plaintiff's own legal interest."

X had alleged that the Niigata-Seoul route license was illegal for the following reasons:

- Y, the Minister of Transport, had allowed the use of a modified runway and landing strip at the airport before their officially announced commencement date, rendering the license non-compliant with the "aviation safety" appropriateness standard of Aviation Act Art. 101(1)(iii).

- Y was illegally permitting the use of a non-instrument runway for instrument landings at the airport, which also made the license non-compliant with the Art. 101(1)(iii) standard.

- The license violated the "public convenience and necessity" standard of Art. 101(1)(i) because the vast majority of passengers on the route were alleged to be tour groups traveling for amusement purposes.

- The license violated the standard concerning the "sound development of air transport" and avoiding excessive supply (Art. 101(1)(ii)) because the route would allegedly create significant overcapacity in transportation services.

The Supreme Court meticulously examined these claims and found that all of these alleged illegalities were "unrelated to X's own legal interest" (jiko no hōritsu-jō no rieki ni kankei no nai ihō). X's legally protected interest, which formed the basis for their potential standing, was the interest in being free from excessive aircraft noise. The Court reasoned that:

- Whether airport facilities were used before an official date, or whether a runway was used for instrument landings (potentially in violation of technical regulations), did not, as argued by X, inherently relate to X's specific legal interest in noise protection. X had not shown how these alleged operational illegalities directly translated into an infringement of their right to be free from intolerable noise.

- Similarly, the purpose of passengers' travel (tourism vs. business) or the economic issue of market overcapacity for airline services were deemed unrelated to the residents' legally protected interest concerning noise levels.

The Outcome: Because the specific grounds of illegality raised by X did not pertain to their own legally recognized interest (protection from significant noise), the Supreme Court concluded that, even if X were found to have plaintiff standing in principle, their claims must be dismissed under ACLA Article 10(1). Since the High Court had dismissed the appeal (albeit for lack of standing), and the Supreme Court cannot alter a judgment to an appellant's disadvantage, X's appeal was ultimately dismissed.

Why This Matters: The "Relevance" Requirement in Asserting Illegality

This 1989 Supreme Court judgment is a crucial illustration of two distinct but related principles in Japanese administrative litigation:

- Plaintiff Standing: It significantly broadened the potential for residents affected by environmental impacts like aircraft noise to gain standing to sue, by looking at the entire legal framework and recognizing the protection of individual interests from severe harm.

- Limitation on Assertable Grounds (ACLA Art. 10(1)): It powerfully demonstrates that merely having standing is not sufficient to win a case. The reasons a plaintiff alleges for an administrative action's illegality must directly relate to the specific legal interest that grants them standing in the first place.

This prevents a plaintiff who has standing based on one type of protected interest (e.g., noise) from using that standing as a platform to litigate entirely unrelated alleged flaws in an administrative decision (e.g., economic policy considerations, or technical breaches of regulations that do not affect their particular interest). As legal commentary points out, ACLA Article 10(1) is understood to stem from the "subjective litigation" character of revocation lawsuits, which are primarily aimed at the protection of the plaintiff's individual rights and interests, rather than being a general review of administrative legality for its own sake.

The Scope of "Related to Own Legal Interest"

The interpretation of what constitutes an illegality "related to one's own legal interest" can be complex. Some legal scholars connect it very closely to the specific legal provisions that form the basis of the plaintiff's standing; under this view, only violations of those particular protective norms can be asserted. Other perspectives might allow for a somewhat broader connection.

This Supreme Court decision is notable for its clear separation of the basis for potential standing (the individual interest in protection from significant aircraft noise, derived from the Aviation Act's overall regulatory scheme) and the specific grounds of illegality actually pleaded by the plaintiffs. It found these pleaded grounds—relating to operational procedures, passenger demographics, and market conditions—to be disconnected from the noise-related interest that could have conferred standing.

Concluding Thoughts

The 1989 airline license case serves as a vital lesson in administrative law. While it opened the door wider for plaintiff standing in environmental impact cases like those concerning airport noise, it also firmly applied the statutory limitation that requires a plaintiff's arguments of illegality to be directly relevant to their own legally protected interests. Successfully challenging an administrative action requires not only being the right person to bring the suit but also arguing the right kind of illegality—one that genuinely pertains to the legal interest that gives that person the right to be heard in court.