Japan’s Article 30-4 Copyright Exception: How AI Developers Can Train Models Legally

TL;DR

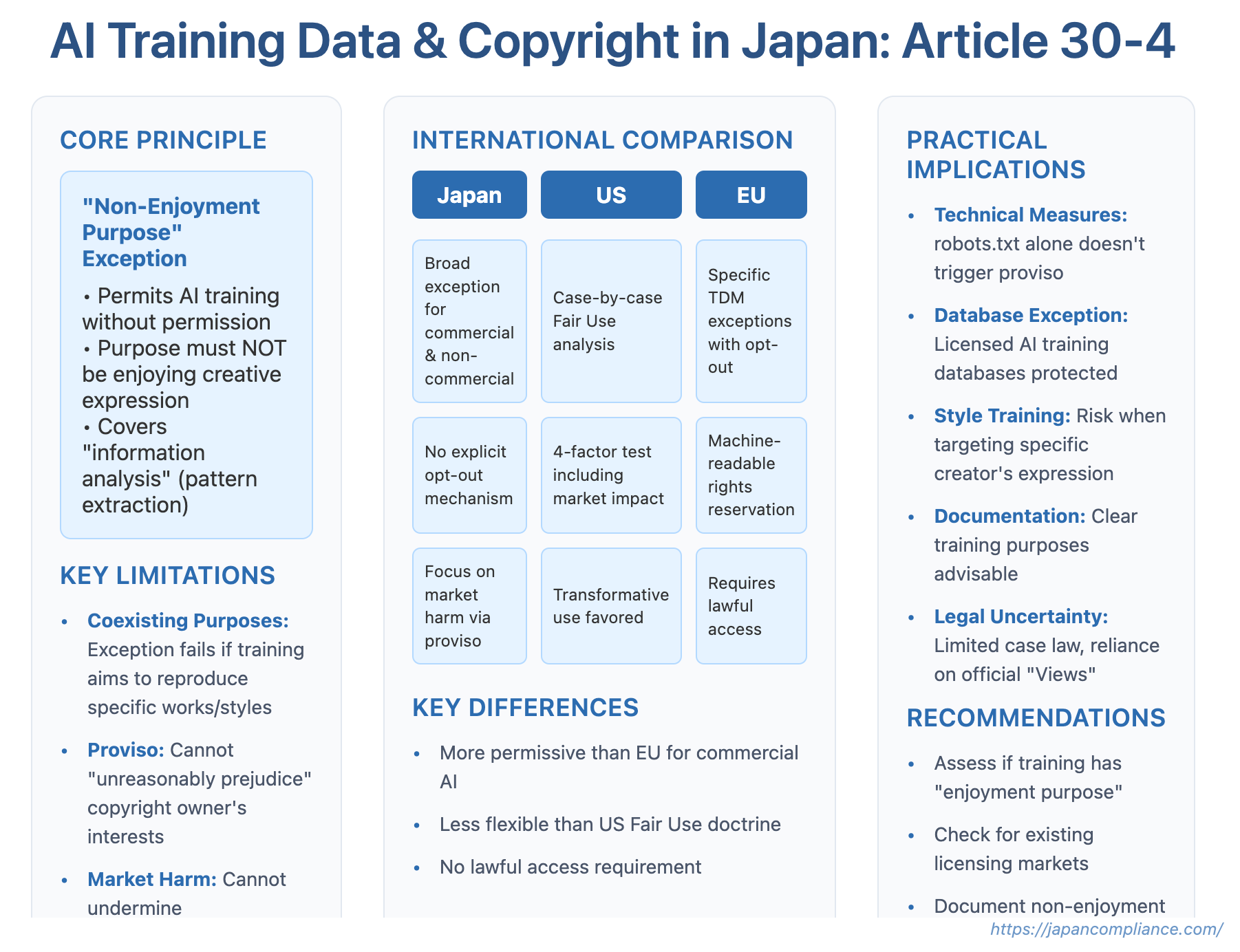

- Article 30-4 of Japan’s Copyright Act broadly permits unlicensed use of works for AI training when the purpose is “non-enjoyment” information analysis.

- The exception vanishes if the same act also aims at user enjoyment (e.g., style imitation) or unreasonably harms a rights-holder’s market.

- Developers should document training purposes, respect technical measures, and assess market impact to stay within the safe zone.

Table of Contents

- The Core Principle of Article 30-4: The “Non-Enjoyment Purpose”

- The Complexity of Coexisting Purposes

- The Limit: The Proviso on Unreasonably Prejudicing Copyright Owners

- Comparison with US Fair Use and EU TDM Exceptions

- Practical Implications and Remaining Uncertainties

- Conclusion

The development of sophisticated Artificial Intelligence (AI), particularly generative AI models, hinges on access to vast datasets for training. This reliance inevitably creates friction with copyright law, as these datasets often include copyrighted text, images, music, and other creative works. How can AI developers legally use this essential data without infringing copyright on a massive scale? Countries around the world are grappling with this question, adopting different approaches – from the flexible factor-based analysis of Fair Use in the United States to the specific Text and Data Mining (TDM) exceptions (with opt-out rights) in the European Union.

Japan stands out with its unique legislative framework, primarily governed by Article 30-4 of its Copyright Act. Enacted initially in 2009 and significantly amended in 2018 to better address digital uses, this provision offers a potentially broad pathway for using copyrighted works for AI training and other forms of "information analysis," provided certain conditions are met. Understanding the scope and limitations of Article 30-4 is crucial for any entity involved in AI development using data potentially subject to Japanese copyright law.

The Core Principle of Article 30-4: The "Non-Enjoyment Purpose"

Article 30-4 permits the exploitation (use) of copyrighted works, without the copyright holder's permission, "in cases where the purpose is not to enjoy the ideas or sentiments expressed in the work for oneself or to have others enjoy the work," to the extent deemed necessary for such purpose. This is often referred to as the "non-enjoyment purpose" (非享受目的 - hi-kyōju mokuteki) exception.

The key concept here is "enjoyment" (享受 - kyōju). The provision operates on the premise that copyright primarily protects the economic interests derived from the appreciation or consumption of a work's creative expression. Uses that do not involve this kind of "enjoyment" – uses that treat the work purely as data or information for analysis – are considered, in principle, outside the core scope of what copyright aims to regulate and thus potentially permissible without a license.

The law explicitly lists examples of non-enjoyment purposes, including use in "testing to develop or put into practical use technology" (Item 1) and, most relevantly for AI, "information analysis" (情報解析 - jōhō kaiseki) (Item 2). Information analysis is defined as "extracting information relating to language, sound, images, or other elemental information from numerous works or large volumes of information, and analyzing it through comparison, classification, or other statistical methods." This definition clearly encompasses the processes involved in machine learning where algorithms analyze data to identify patterns, trends, and correlations to build an AI model.

Therefore, the basic position under Japanese law, as confirmed by official interpretations like the Agency for Cultural Affairs' March 2024 "Perspectives Regarding AI and Copyright" (often referred to as the "Views"), is that using copyrighted works for the purpose of AI training generally falls under "information analysis" and thus benefits from the Article 30-4 exception, as the primary goal is analysis, not the direct enjoyment of the individual works by humans during the training process itself.

The Complexity of Coexisting Purposes

While the principle seems relatively straightforward, complexity arises because a single act of exploitation (e.g., reproducing a work to include it in a training dataset) might serve multiple purposes simultaneously. The "Views" clarify a critical point: Article 30-4 applies only if the purpose of the specific exploitation does not include an "enjoyment purpose." If a non-enjoyment purpose (like information analysis for training) coexists with an enjoyment purpose for the same act, the exception does not apply.

When might an "enjoyment purpose" coexist with an AI training purpose? The "Views" suggest this occurs when the intent behind the learning process is specifically aimed at enabling the AI to output something that allows users to directly appreciate the creative expression of the original works. Examples include:

- Targeted Reproduction: Intentionally performing additional training (including collecting/processing data) specifically to make the AI reproduce all or part of the creative expression found in the training data.

- Style Imitation (as Expression): Training an AI to imitate the "style" of a specific creator, if that style involves concrete creative expressions common across their works (not just abstract ideas or general artistic approaches). The aim here is considered to be enabling the enjoyment of that specific creator's expressive characteristics via the AI output.

This distinction is crucial. Training an AI on a vast dataset for general capabilities likely qualifies as a non-enjoyment purpose. However, fine-tuning a model on a specific artist's works with the express goal of generating outputs "in their style" (where "style" embodies protectable expression) could be seen as having a coexisting enjoyment purpose, thus potentially falling outside the Article 30-4 exception for the act of training itself. Proving this intent might rely on indirect evidence, such as how the AI service is marketed or if infringing outputs are generated frequently.

The Limit: The Proviso on Unreasonably Prejudicing Copyright Owners

Even if a use qualifies as having a non-enjoyment purpose, Article 30-4 contains a vital limitation, often called the proviso (但し書き - tadashigaki). It states that the exception does not apply if the exploitation "unreasonably prejudice[s] the interests of the copyright owner in light of the type and intended use of the work and the manner of the exploitation."

This proviso acts as a safety valve, designed to protect the legitimate market interests of copyright holders when a non-enjoyment use directly conflicts with them. The core question is whether the specific use would harm an existing or potential market for the copyright owner.

The Database Example: A Clear Case of Prejudice

The most commonly cited example of where the proviso applies concerns databases specifically created and marketed for the purpose of information analysis. If such a database exists (e.g., a curated collection of news articles licensed for TDM, or a structured dataset of medical images licensed for research), then reproducing works from that database for information analysis without obtaining the appropriate license would directly undermine the copyright holder's market for that specific product. This is considered unreasonably prejudicial, and Article 30-4 would not permit such unlicensed use.

Potential Markets and Technical Measures: A More Complex Scenario

The "Views" also delve into a more debated scenario involving potential future markets and the effect of technical measures. It suggests that the proviso might apply if:

- Technical measures (like

robots.txtdirectives requesting crawlers not to scrape, paywalls, or login requirements) are in place to restrict access or copying for machine analysis; and - Other factors strongly suggest a potential market for licensing that data specifically for information analysis is likely to emerge (e.g., the rights holder has a history of creating and licensing such databases, or the nature of the data makes it highly suitable for a dedicated analysis market).

In such a situation, deliberately circumventing these technical measures to collect data for AI training could be deemed unreasonably prejudicial because it undermines the copyright holder's ability to develop that potential licensing market.

However, this interpretation requires caution. The "Views" emphasize that merely putting up technical measures or stating an objection to scraping is not sufficient on its own to trigger the proviso. There needs to be a credible indication of a specific, competing market for information analysis use that the scraping directly harms. The legal weight of robots.txt or terms of service prohibiting scraping in triggering the Article 30-4 proviso remains an area of uncertainty, as these are not universally recognized as legally binding copyright controls in the same way as digital rights management (DRM) technologies might be.

Comparison with US Fair Use and EU TDM Exceptions

Japan's Article 30-4 offers a distinct approach compared to other major jurisdictions:

- United States (Fair Use): Fair use (17 U.S.C. § 107) is a flexible, doctrine based on a case-by-case assessment of four factors: (1) the purpose and character of the use (including commercial vs. non-commercial, and transformative use), (2) the nature of the copyrighted work, (3) the amount and substantiality of the portion used, and (4) the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work. While TDM for AI training is widely argued to be fair use, particularly if transformative, its legality isn't definitively settled and depends heavily on specific facts and judicial interpretation. There is no blanket exception.

- European Union (CDSM Directive): The EU's Directive on Copyright in the Digital Single Market (2019) includes two specific TDM exceptions. Article 3 provides an exception for TDM by research organizations and cultural heritage institutions for scientific research purposes. Article 4 provides a broader exception for TDM for any purpose (including commercial AI training), but it crucially allows rights holders to expressly reserve their rights against TDM in a machine-readable way (e.g., via metadata or website terms). If rights are reserved, the Article 4 exception does not apply, and a license is needed. Both EU exceptions also require that the user has lawful access to the works being mined.

Japan's Article 30-4 differs significantly:

- It doesn't distinguish explicitly between commercial and non-commercial purposes (both are potentially allowed if "non-enjoyment").

- It doesn't inherently require "lawful access" as a precondition (though accessing works illegally through other means would still be unlawful).

- It doesn't have an explicit, machine-readable opt-out mechanism like the EU's Article 4. The limitation comes through the proviso's "unreasonable prejudice" test, which focuses primarily on direct market harm, especially concerning dedicated information analysis databases.

Generally, Article 30-4 is considered more permissive for AI training, particularly for commercial purposes, than the EU framework, as long as the use doesn't fall foul of the proviso. However, it lacks the case-by-case flexibility of US Fair Use.

Practical Implications and Remaining Uncertainties

Despite the relative clarity provided by the "Views," several practical questions remain for businesses engaging in AI development using data potentially covered by Japanese copyright:

- Assessing Purpose: Distinguishing between a permissible "non-enjoyment" purpose and an impermissible coexisting "enjoyment" purpose during training can be difficult, especially when the goal is to generate creative outputs or mimic specific styles. Clear documentation of training goals and processes is advisable.

- Determining "Unreasonable Prejudice": Assessing whether a use unreasonably prejudices the copyright owner's interests requires market analysis. Is there an existing, established market for licensing this specific data for information analysis? How likely is such a market to develop? This can be highly fact-specific.

- Effect of Technical Measures and Contracts: The precise legal effect under copyright law of ignoring

robots.txtor violating website terms of service that prohibit scraping for TDM remains ambiguous in the context of the Article 30-4 proviso. While potentially relevant to the "unreasonable prejudice" analysis, they may not automatically disqualify a use from the exception. Contractual breaches are separate legal issues. - Licensed vs. Scraped Data: Data obtained under license agreements often comes with specific usage restrictions that might override Article 30-4 permissions. Conversely, scraping publicly available data relies heavily on Article 30-4, subject to the proviso.

- Lack of Case Law: As AI-related copyright litigation is still nascent in Japan, there is little judicial precedent interpreting Article 30-4 in the specific context of large-scale AI training. Much of the current understanding relies on legislative history and official guidance documents like the "Views."

Conclusion

Japan has established a unique and relatively permissive legal framework for the use of copyrighted works in AI training through Article 30-4. By focusing on the "non-enjoyment purpose" of information analysis, it allows broad use of data, including for commercial AI development, without requiring explicit licenses in many circumstances. However, this permission is not absolute. The coexistence of an "enjoyment purpose" during training can negate the exception, and critically, uses that "unreasonably prejudice" the copyright owner's interests – particularly by undermining established or potential markets for licensing data specifically for analysis – are excluded by the proviso.

For US companies and others involved in AI development that might utilize data subject to Japanese copyright, understanding the nuances of Article 30-4, its "non-enjoyment" condition, and the scope of its market-harm proviso is essential for navigating copyright compliance and managing legal risk. While offering significant latitude compared to some other jurisdictions, the boundaries of permissible use, especially concerning publicly scraped data and the effect of technical access controls, remain areas where further clarification through evolving practice and potentially future court decisions will be crucial.

- Japan's Stance on AI and Copyright: What US Companies Must Know Before Deploying Generative AI

- Decoding Japanese IP Law: How Judicial Interpretation Shapes Patent, Trademark and Copyright Cases

- Balancing Innovation and Security: Strategic IP and R&D Adjustments Under Japan's Patent Non-Disclosure System

- General Understanding on AI and Copyright in Japan – Overview (Agency for Cultural Affairs, May 2024, PDF)