AI Inventorship in Japan: The DABUS Appeal and Global IP Strategy Lessons

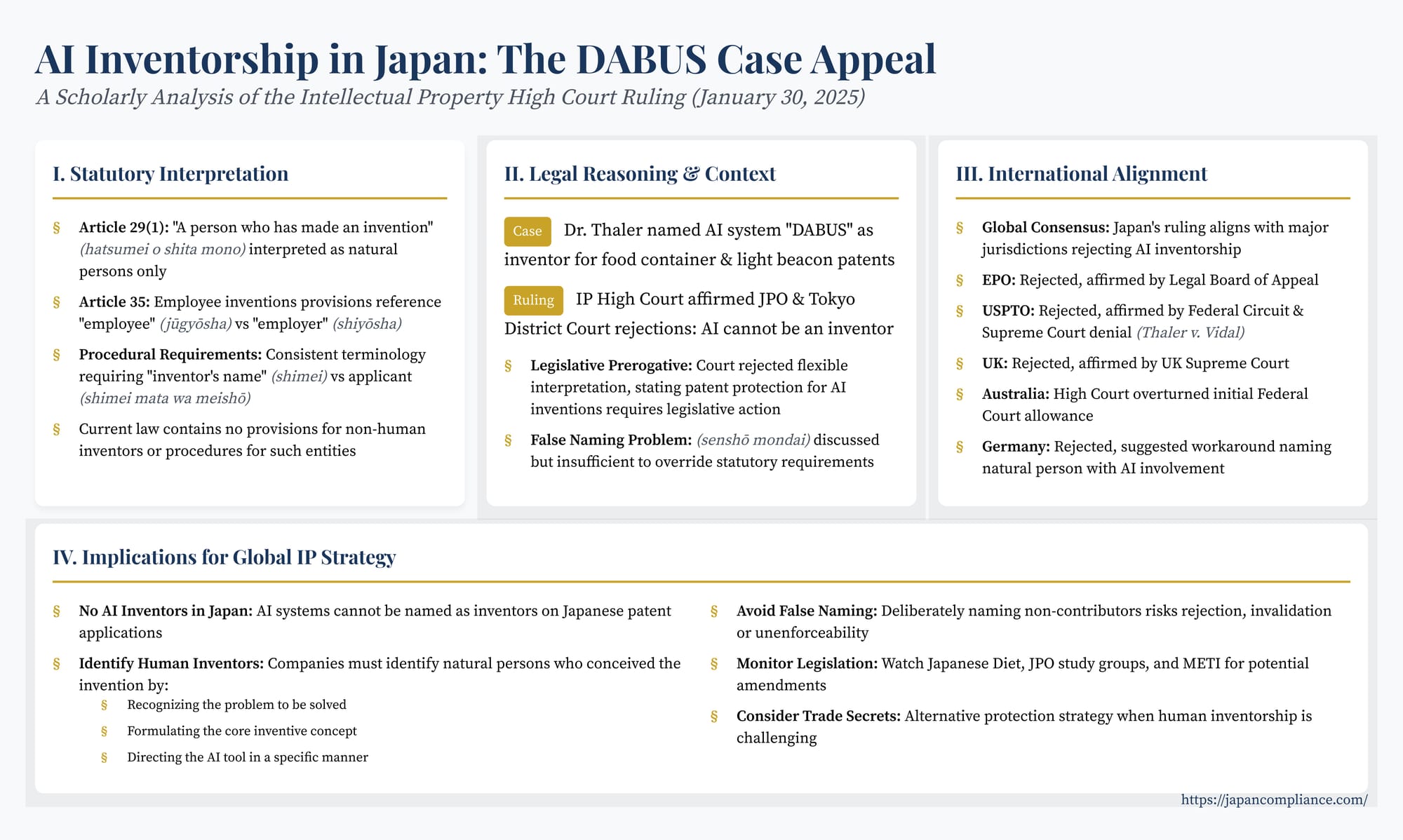

TL;DR: Japan’s IP High Court (Jan 30 2025) confirmed that AI systems like DABUS cannot be named inventors under the Patent Act. Human creative contribution remains essential, but expect legislative debate as global pressure mounts.

Table of Contents

- The DABUS Case in Japan: Background and Lower Court Decision

- The IP High Court’s Ruling: AI Cannot Be an Inventor Under Current Law

- Legislative Prerogative vs. Judicial Interpretation

- The "False Naming" Conundrum

- International Alignment

- Implications for Global IP Strategy

- Conclusion: Human Inventorship Prevails, Legislation Awaited

The rapid advancement of artificial intelligence (AI) is challenging established legal paradigms across numerous fields, and intellectual property law is no exception. One of the most fundamental questions AI poses is to the very definition of inventorship in patent law. Can an AI system, capable of generating novel and non-obvious solutions, be legally recognized as an "inventor"? This question was brought into sharp focus globally by Dr. Stephen Thaler, who filed patent applications in multiple jurisdictions naming his AI system, DABUS ("Device for the Autonomous Bootstrapping of Unified Sentience"), as the sole inventor for creations allegedly conceived autonomously by the machine.

In Japan, as in most major jurisdictions, this challenge reached the judiciary. In a significant ruling on January 30, 2025, Japan's Intellectual Property (IP) High Court delivered a definitive answer regarding the current state of Japanese patent law, confirming that an AI cannot be listed as an inventor. This decision, while aligning with the global trend, provides crucial clarity for companies developing AI-driven innovations and seeking patent protection in Japan, and it underscores the ongoing debate about adapting IP laws for the age of artificial intelligence.

The DABUS Case in Japan: Background and Lower Court Decision

Dr. Thaler filed an international patent application under the Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT) for inventions related to a food container and a light beacon, designating DABUS as the inventor. Upon entering the Japanese national phase, the Japan Patent Office (JPO) rejected the application. The JPO reasoned that the application failed to meet formal requirements because the listed inventor, DABUS, was not a natural person (shizenjin - 自然人).

Dr. Thaler challenged this rejection, arguing that Japan's Patent Act (Tokkyo Hō - 特許法) does not explicitly limit inventorship to natural persons and that denying patent protection for AI-generated inventions would stifle innovation, contradicting the Act's purpose (Article 1) of contributing to industrial development by encouraging invention. The case first went to the Tokyo District Court.

In its decision on May 16, 2024, the Tokyo District Court sided with the JPO, dismissing Dr. Thaler's claim. The court held that the overall structure and provisions of the Japanese Patent Act implicitly presume that an inventor must be a natural person. Dr. Thaler subsequently appealed this decision to the IP High Court, Japan's specialized appellate court for intellectual property matters.

The IP High Court's Ruling: AI Cannot Be an Inventor Under Current Law

On January 30, 2025, the IP High Court affirmed the decisions of the JPO and the Tokyo District Court, definitively ruling that an AI system cannot be recognized as an inventor under the current Japanese Patent Act. The court's reasoning was primarily based on a thorough interpretation of the existing statutory language.

1. Statutory Interpretation of "Inventor":

The court meticulously analyzed several key provisions of the Patent Act:

- Article 29(1): This fundamental provision states that "a person who has made an invention" (発明をした者 - hatsumei o shita mono) that is industrially applicable is entitled to obtain a patent. The court interpreted "person" (mono - 者) in this context as referring to an entity capable of holding rights, which under Japanese law generally pertains to natural persons or legal persons (who typically acquire rights through assignment or employment relationships). Crucially, the initial right arises from the act of invention.

- Article 35 (Employee Inventions): This article deals with inventions made by employees. The court noted that Article 35(1) refers to the inventor as an "employee, etc." (jūgyōsha tō - 従業者等), a term clearly indicating natural persons, especially when contrasted with the term "employer, etc." (shiyōsha tō - 使用者等) which explicitly includes corporations and governmental entities. Furthermore, Article 35(3), which allows the right to obtain a patent for an employee invention to vest originally in the employer under certain conditions, still presupposes that the invention was made by the natural person employee.

- Procedural Requirements (Art. 36, 64, 66, 184-9): The court pointed to consistent terminology used in provisions detailing the contents of patent applications and official gazettes. These sections consistently require the "inventor's name" using the term shimei (氏名), which in Japanese legal drafting typically refers to the name of a natural person. This contrasts sharply with the term used for applicants or patentees, which is "shimei mata wa meishō" (氏名又は名称), explicitly allowing for both individual names (shimei) and corporate designations (meishō). This linguistic distinction, the court found, reinforces the legislative assumption that inventors are natural persons.

Based on this textual analysis, the IP High Court concluded that the Japanese Patent Act, as currently written, only recognizes the "right to obtain a patent" as arising when an invention is made by a natural person (subject to the specific rules for employee inventions transferring rights to employers). The Act contains no provisions contemplating non-human inventors or establishing procedures for granting patents based on inventorship by entities other than natural persons. Therefore, legally, only inventions attributable to human inventors are eligible for patent protection in Japan.

Legislative Prerogative vs. Judicial Interpretation

A key aspect of Dr. Thaler's argument was that AI-generated inventions represent a new technological reality unforeseen when the Patent Act was drafted. He argued that failing to protect these inventions would hinder innovation and run counter to the Act's objective of promoting industrial development (Art. 1). Therefore, the court should interpret the existing law flexibly to include AI inventors.

The IP High Court explicitly rejected this line of reasoning, firmly placing the issue within the domain of legislative policy, not judicial interpretation. The court stated that patent rights are not inherent "natural rights" but statutory creations granted by law to achieve specific policy goals (encouraging invention, developing industry). Whether to extend patent protection to AI-generated inventions, and if so, under what conditions (e.g., should the rights be identical to those for human inventions?), involves complex considerations with broad societal implications.

The court emphasized that such a decision requires careful deliberation by the legislature (the Diet), taking into account potential impacts on the innovation ecosystem, ethical considerations, and the need for international coordination. It is not the role of the judiciary, the court reasoned, to fundamentally alter the established understanding of inventorship by reinterpreting the existing statute to accommodate a scenario the law does not currently address. The lack of explicit provisions for AI inventors simply means that the legislature has not yet made a policy decision to grant them protection.

The "False Naming" (Senshō) Conundrum

A practical concern raised during the proceedings was the "false naming" problem (senshō mondai - 僭称問題). If AI inventors are legally impermissible, might applicants simply name a human – perhaps the AI's owner, programmer, or user – as the inventor, even if the AI largely generated the invention autonomously? This could lead to patents being granted based on inaccurate inventorship information.

The IP High Court acknowledged this as a potential difficulty arising from the current law's inability to accommodate AI invention. However, it maintained that this practical challenge does not justify disregarding the clear statutory requirement to name a natural person inventor. The court pointed out that existing legal mechanisms can address false naming to some extent:

- Grounds for Rejection/Invalidity: Falsely naming an inventor is already grounds for the JPO to reject a patent application (Art. 49(vii)) and can be raised as grounds for an invalidity trial (Art. 123(1)(vi)).

- Invalidity Defense: Even if a patent is granted, false inventorship can be raised as a defense in an infringement lawsuit (Art. 104-3).

The court did concede that the standing requirement for initiating an invalidation trial based on improper inventorship (typically requiring the true inventor or someone who rightfully derived the right from them to bring the claim) poses a problem if the "true" inventor is an AI, which currently has no legal personality or rights. If no natural person can claim to be the rightful inventor, initiating an invalidation trial on these specific grounds might be impossible. However, the court viewed this anomaly as further evidence that the situation falls outside the current legislative scheme, reinforcing the need for legislative clarification rather than judicial intervention.

International Alignment

The IP High Court's decision aligns Japan with the overwhelming international consensus on AI inventorship under existing patent laws. The DABUS applications have been tested in numerous jurisdictions, with major patent offices and courts consistently reaching the same conclusion:

- European Patent Office (EPO): Rejected, affirmed by the Legal Board of Appeal (inventor must be a natural person under the EPC).

- United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO): Rejected, affirmed by the Federal Circuit and certiorari denied by the Supreme Court (Thaler v. Vidal) (inventor must be an individual under the US Patent Act).

- United Kingdom Intellectual Property Office (UKIPO): Rejected, affirmed by the UK Supreme Court (inventor must be a natural person).

- Australia: Rejected by the High Court, overturning an initial Federal Court decision that had allowed AI inventorship (inventor must be human).

- Germany: Rejected by the Federal Patent Court, although the court suggested a practical workaround of naming a natural person along with supplementary information about the AI's involvement (this does not grant the AI inventor status).

- South Africa: Notably, a patent was granted, but this is widely attributed to South Africa's registration system lacking substantive examination of inventorship requirements.

This global alignment underscores that the challenge posed by AI inventorship is rooted in the fundamental structure and language of existing patent statutes worldwide, which were drafted with human inventors in mind.

Implications for Global IP Strategy

The IP High Court's ruling provides welcome legal certainty regarding AI inventorship in Japan under the current legal framework. For companies developing and seeking to protect AI-driven innovations globally, including in Japan, key strategic implications arise:

- No AI Inventors in Japan (Currently): It is definitively established that AI systems cannot be named as inventors on Japanese patent applications. Any application listing only an AI will be rejected on formal grounds.

- Identify Human Inventors: For inventions developed with significant AI assistance, companies must identify one or more natural persons who qualify as inventors under Japanese law. Japanese practice, like that in many other jurisdictions, generally considers inventorship based on the "conception" of the invention. This typically involves the human(s) who:

- Recognized the problem to be solved.

- Formulated the core inventive concept or approach.

- Directed the AI tool in a specific manner towards achieving that concept.

- Recognized the AI's output as a viable solution to the problem.

- Adapted or refined the AI's output for practical application.

Thorough documentation of the human contribution throughout the development process is crucial.

- Avoid False Naming: While tempting as a workaround, deliberately naming individuals who did not genuinely contribute to the conception of the invention carries significant risks. Such patents are vulnerable to rejection, invalidation challenges, or being deemed unenforceable due to inequitable conduct or fraud on the patent office.

- Monitor Legislative Developments: The IP High Court explicitly pointed towards the need for legislative action. Companies heavily invested in AI R&D should closely monitor discussions within the Japanese Diet, JPO study groups, and relevant ministries (like METI) regarding potential future amendments to the Patent Act to address AI inventorship and ownership. Similar monitoring is necessary globally, as international consensus or divergence on legislative solutions will impact global filing strategies.

- Consider Trade Secrets: For AI-generated innovations where identifying human inventors is challenging or where the output is more akin to a discovery than a patentable invention, trade secret protection remains a vital alternative or complementary strategy. This requires implementing robust measures to maintain confidentiality.

Conclusion: Human Inventorship Prevails, Legislation Awaited

The Japanese IP High Court's decision in the DABUS appeal confirms that, under the existing Patent Act, the concept of an "inventor" is exclusively limited to natural persons. This ruling aligns Japan with the predominant global judicial view and provides clear guidance for applicants seeking patent protection in the country: AI cannot be legally named as an inventor.

The court firmly positioned the question of protecting AI-generated inventions as a matter for legislative policy, not judicial reinterpretation. It acknowledged the profound questions AI raises about the future of innovation and the purpose of the patent system but concluded that addressing these requires careful consideration by lawmakers, informed by societal debate and international developments.

For businesses leveraging AI in their R&D efforts, the practical takeaway is clear. Patent applications in Japan must identify human inventors based on their contribution to the conception of the invention. While AI is a powerful tool, inventorship, for now, remains a human attribute in the eyes of Japanese patent law. Companies must focus on accurately identifying and documenting human ingenuity within the AI-assisted innovation process, while keeping a close watch on the legislative horizon for potential future changes to Japan's IP framework in response to the ongoing AI revolution.

- Navigating Japan’s Evolving IP Landscape: UGC, Derivative Works, and Creator Rights

- Generative AI in Japan: Understanding Copyright Risks and Opportunities

- Legal-Tech Transformation in Japan: AI Adoption, Governance and the Future of Corporate Legal Departments

- Japan Patent Office — AI-related Inventions Portal

https://www.jpo.go.jp/e/system/patent/gaiyo/ai/index.html