Agent's Bank Account, Principal's Money? A Japanese Supreme Court Case on Deposit Ownership

Date of Judgment: February 21, 2003

Case Name: Claim for Deposit Return, Restoration from Provisional Execution, and Damages

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench

Introduction

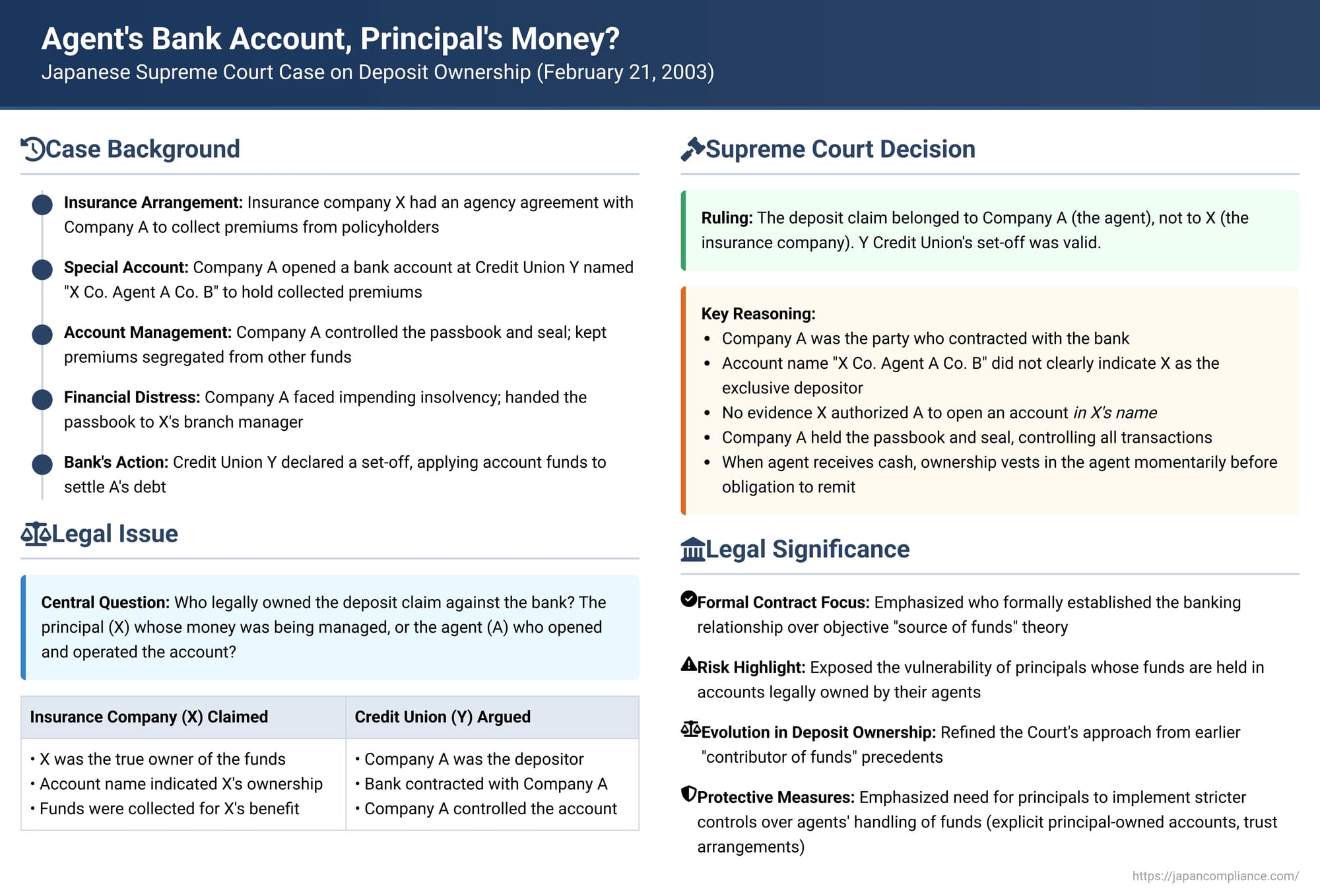

In many business relationships, agents handle funds on behalf of their principals. A common practice is for the agent to set up a dedicated bank account to manage these monies. But a critical legal question can arise: who truly "owns" the funds in such an account if the agent faces financial trouble or if disputes occur with the bank? Does the deposit belong to the agent who opened and operates the account, or to the principal whose funds are being managed? A Japanese Supreme Court decision from February 21, 2003, delved into this issue, particularly in the context of an insurance agency holding premiums for an insurance company.

The Insurance Premiums Account: A Case Study

The facts leading to the Supreme Court were as follows:

- The Parties and the Arrangement:

- X (Fuji Fire & Marine Insurance Co.): A major insurance company.

- Company A (Yano Construction Engineering Co.): An authorized insurance agent for X, operating under a formal agency agreement. "B" was the representative of Company A.

- Y: A credit union where Company A maintained a bank account.

- The Special Bank Account: To manage the insurance premiums it collected on behalf of X, Company A opened an ordinary deposit account at Y Credit Union's C branch. The account was opened in the name of "X (Co.) Agent A (Co.) B" (interpreted as "Fuji Fire & Marine Insurance Co. - Agent: Yano Construction Engineering Co. - Representative B").

- Company A had procedures to keep the collected premiums for X segregated from its own general funds, using dedicated safes or collection bags before depositing them into this "Subject Account."

- It was understood that only premiums collected for X would be deposited into this account, and indeed, no other funds were ever mixed into it.

- Company A (the agent) held the passbook and the registered seal (inkan) for the Subject Account. Furthermore, any interest earned on the deposit in the Subject Account was retained by Company A.

- Agent's Financial Distress and Bank's Action: Company A subsequently faced financial difficulties, to the point where it was about to issue a second dishonored bill (a strong indicator of impending insolvency in Japan). In this situation, Company A handed over the passbook and registered seal for the Subject Account to a branch manager of X (the insurance company).

On the very same day, Y Credit Union, which had an outstanding loan or other monetary claim against Company A, took action. Y Credit Union declared a set-off, applying the balance in the Subject Account against the debt owed to it by Company A. - Insurance Company Sues Bank: X (the insurance company) then sued Y Credit Union, demanding the withdrawal and return of all funds in the Subject Account. X's core argument was that the deposit monies rightfully belonged to X, not to its agent, Company A.

- Lower Court Rulings: Both the first instance court and the High Court ruled in favor of X (the insurance company). Their reasoning generally followed the principle that the party who is the ultimate source or contributor of the funds for a deposit (出捐者 - shusshaensha) should be considered the owner of the resulting deposit claim. They determined that given the purpose of the account (to hold X's premiums), X's substantial economic interest in the funds, and aspects of how the account was supposed to be managed for X's benefit, X was the true owner of the deposit.

Y Credit Union appealed this outcome to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decision

The Supreme Court, in its judgment on February 21, 2003, overturned the lower courts' decisions. It ruled that the deposit claim associated with the Subject Account belonged to Company A (the agent), not to X (the insurance company). This meant Y Credit Union's set-off against Company A's debt was, in principle, valid concerning this account.

Core Reasoning of the Majority Opinion:

- Who Contracted with the Bank? The Court first looked at who formally established the banking relationship. It was Company A (the agent) that entered into the ordinary deposit agreement with Y Credit Union and opened the Subject Account.

- Interpretation of the Account Name: The account name "X (Co.) Agent A (Co.) B" was not, in the Court's view, a clear indication that X (the insurance company) was the contracting party or the depositor, to the exclusion of Company A. It could equally, or more plausibly, indicate an account operated by Agent A in the course of its agency for Principal X.

- No Evidence of Agency for Account Opening in X's Name: The record showed no evidence that X had specifically authorized Company A to act as its agent for the purpose of opening a deposit account in X's name directly with Y Credit Union. For X to be the depositor, X would typically have to be the direct contracting party with the bank, either itself or through a duly authorized agent acting explicitly on X's behalf in forming the bank contract.

- Control and Management of the Account: Company A held the passbook and the registered seal, and Company A exclusively handled all deposits into and withdrawals from the Subject Account. Therefore, the Court concluded that Company A was, both in name (as suggested by the practical operation) and in substance, the manager and controller of the account.

- Ownership of the Deposited Money (Cash Premiums): This was a critical point in the Court's reasoning.

- The Court invoked a principle regarding the ownership of money: when an agent (Company A) receives cash (the insurance premiums from policyholders) on behalf of a principal (X), the ownership of that physical cash generally vests in the agent who takes possession of it. This is due to the nature of money, where possession and ownership are usually intertwined.

- Upon receiving the cash, the agent (Company A) then incurs a contractual obligation to pay an equivalent sum of money to the principal (X).

- Therefore, when Company A deposited the collected premiums into the Subject Account, it was, in the eyes of the law regarding property in cash, depositing money that it (Company A) momentarily owned, even though those funds were ultimately due to X.

- X (the insurance company) would only acquire ownership of money equivalent to the premiums when Company A actually remitted those funds to X (e.g., after Company A withdrew them from Y Credit Union for that purpose).

- Conclusion on Deposit Ownership: Based on these factors – Company A being the party who contracted with the bank, effectively managed the account, and was deemed the owner of the cash at the moment of deposit – the Supreme Court concluded that the deposit claim (the right to demand the funds from Y Credit Union) belonged to Company A (the agent), not to X (the insurance company).

The Court added that internal arrangements between X and A, such as A's duty to keep the premiums separate or contractual restrictions on A's use of these funds, did not alter the determination of who the depositor was in the direct legal relationship with Y Credit Union.

The Dissenting Opinion

Justice Fukuda, in a dissenting opinion, criticized the lower courts' reliance on the "contributor of funds" theory. However, he reached the same conclusion as the lower courts (that X owned the deposit), but via different reasoning. He argued that the agency agreement between X and A impliedly authorized A to open the premium collection account as X's agent and for X's benefit. The account name, including "X Co. Agent A Co.," should be interpreted as X establishing the account through its agent A. Thus, the control by A was in its capacity as X's agent for X's account. Therefore, X should be deemed the depositor.

Navigating Deposit Ownership: A Complex Area

This 2003 Supreme Court decision marked an important point in the ongoing judicial discussion in Japan about who is legally considered the "depositor" and owner of a bank account, especially when funds might originate from or be beneficially owned by someone other than the formal account opener or manager.

Shift from the "Objective/Source of Funds" Theory?

Previous Supreme Court precedents, particularly concerning certain types of time deposits, had sometimes leaned towards an "objective theory" (客観説 - kyakkansetsu), which tended to identify the depositor as the person who provided the funds (the 출자자 - shusshaensha) for the deposit, especially if the bank itself had no particular interest in who the true depositor was beyond that individual. The rationale was often to protect the person whose money was actually at stake.

The 2003 judgment, however, placed greater emphasis on:

- The formal aspects of who entered into the deposit contract with the bank.

- The name in which the account was effectively held and operated vis-à-vis the bank.

- Who exercised actual control over the account (possession of passbook and seal).

- The technical legal ownership of cash at the moment it was deposited.

This approach appears more aligned with general principles of contract party identification than a pure "source of funds" test. Legal commentators have suggested that this might represent an evolution or refinement in the Supreme Court's approach, possibly influenced by changes in the banking environment that place more emphasis on knowing the customer.

Implications for Principals and Agents

The majority decision highlights a significant risk for principals whose agents handle their funds: if the agent deposits those funds into an account that is legally deemed to be the agent's own account with the bank, those funds can become exposed to the agent's creditors or to set-off actions by the bank itself if the agent owes money to the bank.

- Protecting the Principal's Interest: To mitigate this risk, principals may need to implement stricter contractual controls over their agents regarding the handling of funds. This could include:

- Requiring agents to open accounts explicitly in the principal's name (with the agent perhaps having limited authority to operate it).

- Establishing formal trust arrangements for holding client funds.

- Implementing direct payment systems where feasible, bypassing agent-held accounts.

- The dissenting opinion's approach, seeking to find an implied agency for opening the account on behalf of the principal, reflects a desire to protect the principal's substantive interest, but the majority focused on the formal relationship with the bank.

Broader Context

This case is often discussed alongside others dealing with mistaken bank transfers or the general problem of identifying the true owner of a deposit when there are multiple interested parties. The overarching theme is a tension between formal contractual relationships with financial institutions and the substantive economic ownership or entitlement to funds. While the Supreme Court in this instance prioritized the formal depositor-bank relationship based on who opened and controlled the account, the specific facts, including the account naming and the agent's role, were central to its analysis.

Conclusion

The 2003 Supreme Court decision underscores that when an agent opens and controls a bank account, even for the dedicated purpose of managing a principal's funds, the legal ownership of the deposit claim against the bank will often be found to lie with the agent, unless there is clear evidence that the principal was the direct contracting party with the bank for that account. The Court's emphasis on the formal aspects of the banking relationship and the technical ownership of cash at the point of deposit means that principals must be diligent in structuring how their agents handle finances to protect their interests, especially against the risk of the agent's insolvency or claims from the agent's own creditors.