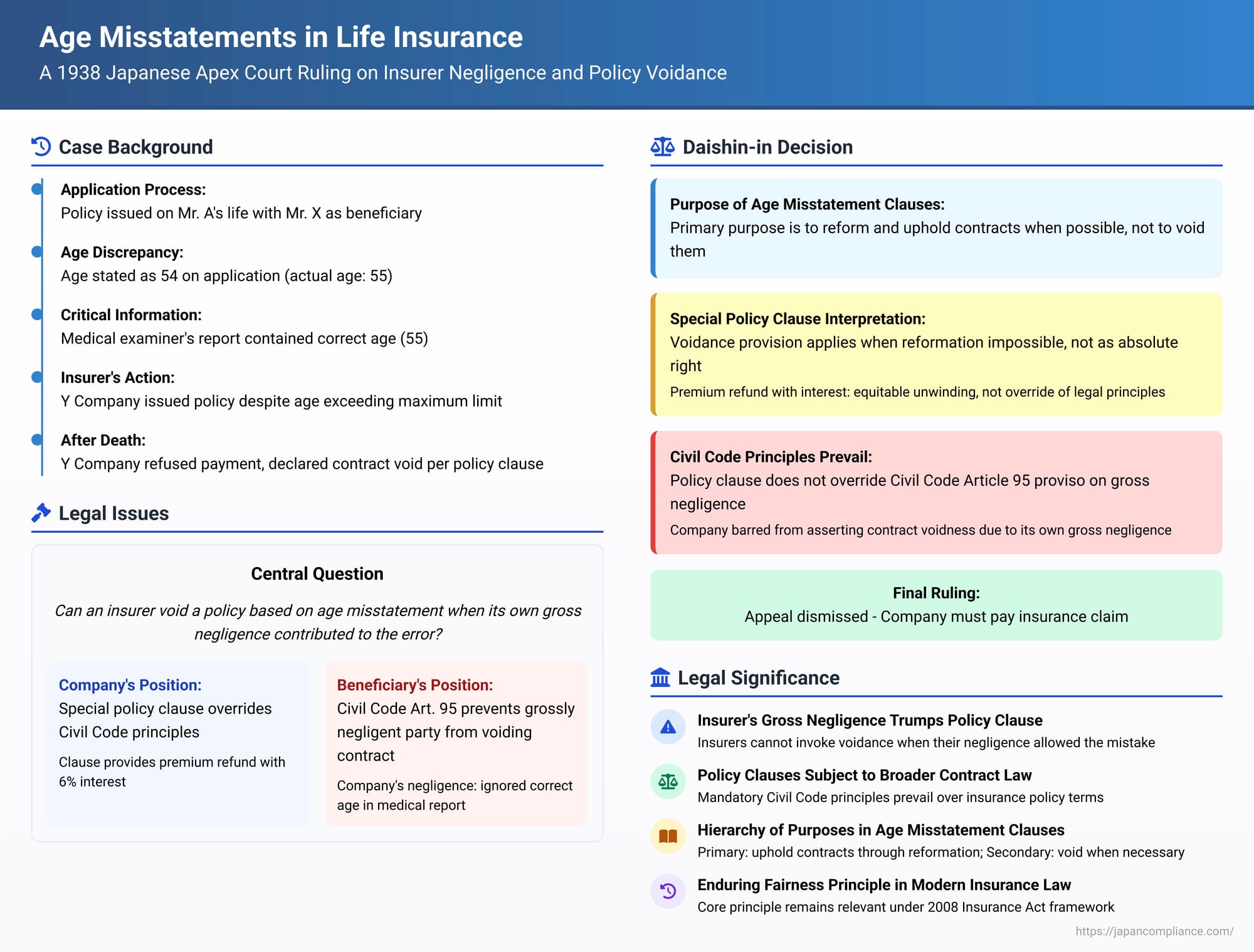

Age Misstatements in Life Insurance: A 1938 Japanese Apex Court Ruling on Insurer Negligence and Policy Voidance

Judgment Date: March 18, 1938

Court: Daishin-in (Great Court of Cassation), Second Civil Department

Case Name: Insurance Claim Case

Case Number: Showa 12 (O) No. 2067 of 1937

Introduction: The Critical Importance of Age in Life Insurance

The age of the individual whose life is to be insured is a cornerstone of any life insurance contract. It is a fundamental factor used by insurers to assess the risk of mortality, calculate appropriate premiums, and determine eligibility for coverage. An incorrect statement of age on an insurance application can, therefore, have significant legal consequences if discovered later.

Life insurance policies frequently contain specific clauses that address how such age misstatements will be handled. These clauses might provide for the adjustment of benefits or premiums if the correct age is still within the insurer's acceptable range, or they might stipulate that the contract is void if the true age falls outside the insurer's established age limits for issuing that particular type of policy.

But what happens if the insurer itself was arguably negligent in failing to detect an age discrepancy, especially if correct age information was available to it during the underwriting process? Can an insurer still rely on a policy clause to declare a contract void due to an age misstatement if its own gross negligence contributed to the error not being caught at the outset? This complex interplay between contractual provisions, the legal doctrine of "mistake" (sakugo), and the consequences of a party's own negligence was explored in a significant, albeit very early, 1938 decision by the Daishin-in, Japan's highest court at the time.

The Facts: An Age Over the Limit, A Policy Issued, and a Contested Claim

The case involved a life insurance policy taken out on the life of Mr. A. Mr. X was named as the beneficiary. At the time the contract was concluded, Mr. A's age was mistakenly stated on the insurance application form as "54 years old."

In reality, Mr. A's actual age at that time was 55. This was a critical difference because, according to Y Life Insurance Company's underwriting rules and premium tables, the age of 55 was above the maximum age limit for which it would issue the type of life insurance policy in question.

However, a crucial piece of information existed within Y Company's own records from the underwriting process. The medical examiner's report (診査報状 - shinsa hōjō), prepared by a physician acting on behalf of Y Company to assess Mr. A's health and insurability, did contain Mr. A's correct birthdate and accurately stated his age as 55. Despite this correct information being available to it via its own appointed medical examiner, Y Company proceeded to issue the life insurance policy, apparently based on the incorrect age of 54 provided on the application form.

Some time later, Mr. A passed away, and Mr. X, as the beneficiary, duly filed a claim for the death benefit. Y Life Insurance Company denied the claim. It declared the contract void, relying on a specific clause within its policy (referred to in the judgment as "the subject special clause"). This clause stipulated that if the insured's actual age at the time of the contract's inception was found to be outside the age range specified in the company's official premium tables (i.e., if the insured was older than the maximum insurable age or younger than the minimum), the insurance contract would be considered void. In such an event, the clause provided that any premiums already paid by the policyholder would be refunded, with 6% compound interest added. Y Company argued that since Mr. A's true age of 55 was outside its insurable limits, this clause gave it the clear right to void the contract.

The Lower Court's Finding: Insurer's Gross Negligence Precludes Voiding the Contract

The case had made its way through the lower courts. The appellate court (the "original judgment" from which the appeal to the Daishin-in was taken) had ruled against Y Life Insurance Company and in favor of the beneficiary, Mr. X.

The appellate court found that Y Company had been grossly negligent (重過失 - jūkashitsu) with respect to the misstatement of Mr. A's age. This finding of gross negligence was based squarely on the fact that Y Company's own medical examiner's report – a document prepared by its own agent in the underwriting process – contained Mr. A's correct age (55). The insurer's failure to note and act upon this correct information, and instead issue a policy based on the incorrect age from the application, was deemed a serious lapse.

Because of this finding of gross negligence on the part of Y Company, the appellate court held that the insurer was barred from asserting the nullity (voidness) of the contract due to its own mistake about Mr. A's age. In reaching this conclusion, the lower court invoked the proviso to Article 95 of Japan's (then-applicable) Civil Code. This important proviso generally prevented a party who was themselves grossly negligent concerning a mistake they had made from later claiming that a contract was void due to that mistake.

The Insurer's Argument on Appeal to the Daishin-in: Does the Policy Clause Override the Civil Code Rule on Grossly Negligent Mistake?

Y Life Insurance Company appealed the appellate court's decision to the Daishin-in. Its central argument was that its special policy clause – the one providing for the contract to be void if the insured's age was outside the insurable limits, but also stipulating a seemingly generous refund of premiums with 6% compound interest – was a specific contractual agreement that was intended to comprehensively govern the precise situation of age misstatement.

Y Company contended that this specific policy clause should take precedence over, and effectively exclude the application of, the general provision in the Civil Code (Article 95 proviso) regarding a grossly negligent party's inability to assert voidness due to their own mistake. The insurer's position was that the clause's provision for an enhanced premium refund (including compound interest) was intended as a fair and contractually agreed-upon resolution for such age discrepancy scenarios, and that this specific contractual remedy should apply even if the insurer itself had been negligent in initially overlooking the correct age information.

The Daishin-in's Decision (March 18, 1938): Policy Clause Does Not Oust General Civil Code Principles Regarding Gross Negligence

The Daishin-in dismissed Y Life Insurance Company's appeal. It upheld the lower appellate court's decision, meaning Y Company could not void the contract and was therefore liable to pay the insurance claim to Mr. X. The Daishin-in's reasoning was as follows:

The General Purpose of Age Misstatement Clauses in Insurance Policies

The Daishin-in first considered the general purpose and typical operation of policy clauses that address misstatements of an insured's age:

- It acknowledged the fundamental point that an insured's age is critically important for the insurer's risk assessment in life insurance, and a mistake regarding age can, in principle, lead to the invalidity (voidness) of an insurance contract.

- However, the Court immediately qualified this by stating that even when such an age mistake occurs, if the insured's actual age is still within the insurer's acceptable insurable age range (or is perhaps even younger than what was stated on the application), the contract does not necessarily have to be voided. In such situations, insurers typically have methods – such as correcting the premium amount to reflect the true age, or adjusting the sum insured – to effectively reform the contract to what it would have been had the correct age been known from the outset. This approach allows the insurer to maintain the benefit of a contract it successfully concluded, without causing any undue loss or prejudice to the policyholder.

- The Daishin-in interpreted the primary purpose of policy clauses like "the subject special clause" in Y Company's policy as being precisely this: to provide a mechanism for reforming and thereby upholding the validity of the contract through adjustment, whenever the age misstatement still leaves the insured individual within a generally insurable age bracket according to the insurer's rules.

The Clause's Application When the Insured's Actual Age is Outside Insurable Limits

The Daishin-in then specifically addressed the part of the policy clause that applied when, as was the situation in Mr. A's case, the insured's actual age exceeded the insurer's maximum insurable age limit, making such reformation impossible because the insurer would not have issued a policy at that true age in the first place.

- In this specific scenario, the policy clause provided for the contract to be declared void and for all premiums paid to be refunded with a specified rate of compound interest.

- The Daishin-in viewed this part of the clause not as an independent and overriding rule that granted the insurer an absolute right to void the contract under all circumstances if the age was out of limits. Instead, it saw this voidance and refund provision as a consequence that naturally flows when reformation to a valid contract based on the true age is not possible because that true age itself falls outside the insurer's own definition of insurability. The provision for refunding premiums with an enhanced rate of interest was seen by the Court as a specific contractual measure to deal with the equitable unwinding of a contract that could not be validated due to the fundamental issue of the insured's age being beyond the acceptable underwriting limits.

No Exclusion of the Civil Code's Rule on Gross Negligence (Article 95 Proviso)

This led to the Daishin-in's crucial finding regarding the insurer's argument that its policy clause should displace general Civil Code principles:

- The Court found that there was nothing in the wording or the underlying purpose of Y Company's special policy clause to suggest that it was intended by the parties to exclude or override the application of the Civil Code Article 95 proviso.

- This proviso, a fundamental principle of contract law, generally bars a party who was themselves grossly negligent in making or failing to recognize a mistake from later taking advantage of that mistake to assert the nullity of a contract.

- The fact that Y Company's policy clause provided for a return of premiums with 6% compound interest (a rate that might have been considered generous at the time) was not seen by the Daishin-in as a contractual "trade-off" that would allow the insurer to escape the legal consequences of its own gross negligence. The Court viewed the specific interest provision as likely reflecting nothing more than Y Company's confidence, as an insurance business operator, in its ability to generate such returns on the premiums it had received during the period the policy was mistakenly in force. It did not interpret this as a pre-agreed justification for the insurer to ignore its own serious error in overlooking the correct age information that was readily available to it through its own medical examiner's report.

Conclusion of the Daishin-in

Since the lower appellate court had made a factual finding that Y Life Insurance Company had indeed been grossly negligent (as its own medical examiner's report contained Mr. A's correct age of 55, yet the company proceeded to issue the policy apparently based on the incorrect age of 54 from the application form), Y Company was barred by the proviso to Civil Code Article 95 from asserting that the contract was void due to its mistake regarding Mr. A's age. This was true notwithstanding the specific terms of its special policy clause concerning age misstatements, as that clause was not interpreted to oust this fundamental principle of contract law regarding grossly negligent mistakes.

Analysis and Implications of this Early but Foundational Ruling

This 1938 Daishin-in decision, despite its vintage, established a very important principle in Japanese insurance law regarding the interplay between specific policy clauses and general principles of contract law, particularly in the context of insurer negligence.

1. Insurer's Gross Negligence Can Trump a Policy's Voidance Clause for Age Discrepancies:

The most significant takeaway from this judgment is its clear affirmation that even if a life insurance policy contains a clause that seems to give the insurer an absolute right to declare the contract void if the insured's true age is found to be outside the company's insurable limits, the insurer may be prevented from invoking this voidness if the insurer itself was grossly negligent in failing to ascertain or act upon the correct age, especially when that correct information was already within its own possession or available to it through its own agents (like an examining physician) during the underwriting process.

2. Insurance Policy Clauses are Generally Interpreted in Light of, and Subject to, Overriding Principles of General Contract Law:

The Daishin-in's approach demonstrates that specific clauses within an insurance policy, particularly those dealing with fundamental issues like mistake or grounds for voiding a contract, will generally be interpreted by Japanese courts in conjunction with, and usually subject to, any overriding mandatory principles of general contract law. In this case, the Civil Code's rule preventing a party from taking advantage of its own grossly negligent mistake (the Article 95 proviso) was held to prevail over a literal interpretation of the policy's voidance clause that might have otherwise seemed to give the insurer an unfettered right. A policy clause cannot easily be used to allow a party to contract out of the basic legal consequences of its own gross fault, particularly if doing so would lead to an unfair or unconscionable result.

3. The Hierarchy of Purpose in Interpreting Age Misstatement Clauses:

The Daishin-in effectively established a hierarchy when interpreting the purpose of typical age misstatement clauses in life insurance policies of that era. It viewed the primary purpose of such clauses as being to facilitate the continuation and validation of the insurance relationship through adjustment or reformation of terms (like premiums or benefits) whenever possible – that is, when the insured's true age, even if misstated, still falls within a generally insurable range. The provision for voiding the contract was seen as a secondary consequence, applicable mainly in cases where such reformation was impossible because the insured's true age was fundamentally outside the insurer's acceptable underwriting limits. This primary purpose of upholding contracts where feasible was not seen by the Court as being compatible with allowing an insurer to void a contract due to an age issue that it had itself been grossly negligent in overlooking.

4. Modern Relevance and the Evolution of Insurance Law:

It is essential to consider this 1938 Daishin-in judgment within its historical context, while also acknowledging the significant evolution of Japanese insurance law since that time.

- As legal commentary (such as the PDF provided with this case) often highlights, while this Daishin-in ruling framed the core issue primarily in terms of the legal doctrine of "mistake" (sakugo) under the Civil Code, modern Japanese insurance law scholarship and contemporary practice tend to analyze age misstatements more frequently as a potential breach of the insured's "duty of disclosure" (kokuchi gimu) under insurance-specific statutes (principally, now, the Insurance Act of 2008).

- Japan's current Insurance Act (e.g., Article 55) provides a detailed framework for how an insurer can respond to a breach of the duty of disclosure by an insured or policyholder. If the breach (such as a misstatement of age) was due to the insured's own bad faith or gross negligence, the insurer generally has the right to rescind the contract. However, if the misstatement was due to only simple negligence on the part of the insured, or was made innocently, the insurer's right to rescind is typically more restricted or may not exist at all for that reason alone.

- This raises interesting questions about how a policy clause like the one in this 1938 Daishin-in case (which provided for voidance if the actual age was outside the insurer's limits, without explicit reference to the policyholder's level of fault in making the misstatement) would be viewed by a Japanese court today under the current Insurance Act. Legal commentary suggests that such a clause, if it sought to impose voidness even for innocent or merely simply negligent age misstatements where the insurer itself was also demonstrably at fault (particularly grossly negligent, as in this case), might well be seen as conflicting with the Insurance Act's more nuanced and often more policyholder-protective approach to remedies for disclosure breaches. The Insurance Act contains provisions (e.g., Article 65) that can render policy terms invalid if they unilaterally disadvantage the policyholder in a manner contrary to mandatory statutory provisions.

- Nevertheless, the fundamental principle that age is a critical element in life insurance underwriting remains unchanged. It is also still true that insurers have a responsibility to conduct their underwriting with due care. The Daishin-in's underlying message – that an insurer cannot easily escape liability by pointing to an applicant's mistake if the insurer's own gross negligence allowed that mistake to go uncorrected when it had the means to discover the truth – continues to resonate as a principle of fairness in contractual dealings.

Conclusion

The March 18, 1938, decision by the Daishin-in is a significant early Japanese judgment that powerfully affirmed that an insurer's own gross negligence can prevent it from voiding a life insurance policy due to a mistake regarding the insured's age. This holds true even if the insured's actual age was outside the company's normally insurable age limits and even if a specific policy clause appeared to give the insurer the right to declare the contract void in such circumstances.

The Daishin-in interpreted the primary purpose of typical age misstatement clauses in life insurance policies of that era as being to facilitate the continuation of the insurance relationship through adjustment or reformation of policy terms whenever the insured's true age still fell within an insurable range. The provision for voiding the contract when the true age was found to be outside insurable limits was seen by the Court more as a consequence that flows from the impossibility of such reformation, rather than as a clause that grants the insurer an unfettered right to void the contract irrespective of its own serious fault in failing to note correct age information that was already in its possession (for example, from its own medical examiner's report).

This important ruling underscores the fundamental legal principle that specific contractual provisions within insurance policies will be interpreted by Japanese courts in light of, and will generally be held subject to, broader mandatory principles of contract law. In this case, the Civil Code's rule preventing a party from taking advantage of a situation created by its own gross negligence was deemed to prevail. While the statutory framework for insurance law and the specifics of disclosure duties have evolved considerably in Japan since 1938 with the enactment of the modern Insurance Act, this early Daishin-in decision remains an important historical illustration of the judiciary's enduring role in ensuring fairness and equity in the application and enforcement of insurance contract terms.