Aftermarket Competition in Japan: Balancing IP Rights and Antitrust Law – Lessons from a Printer Cartridge Case

Japan’s courts explain when enforcing printer‑cartridge patents crosses antitrust lines—essential reading for OEMs, recyclers and IP counsel.

TL;DR

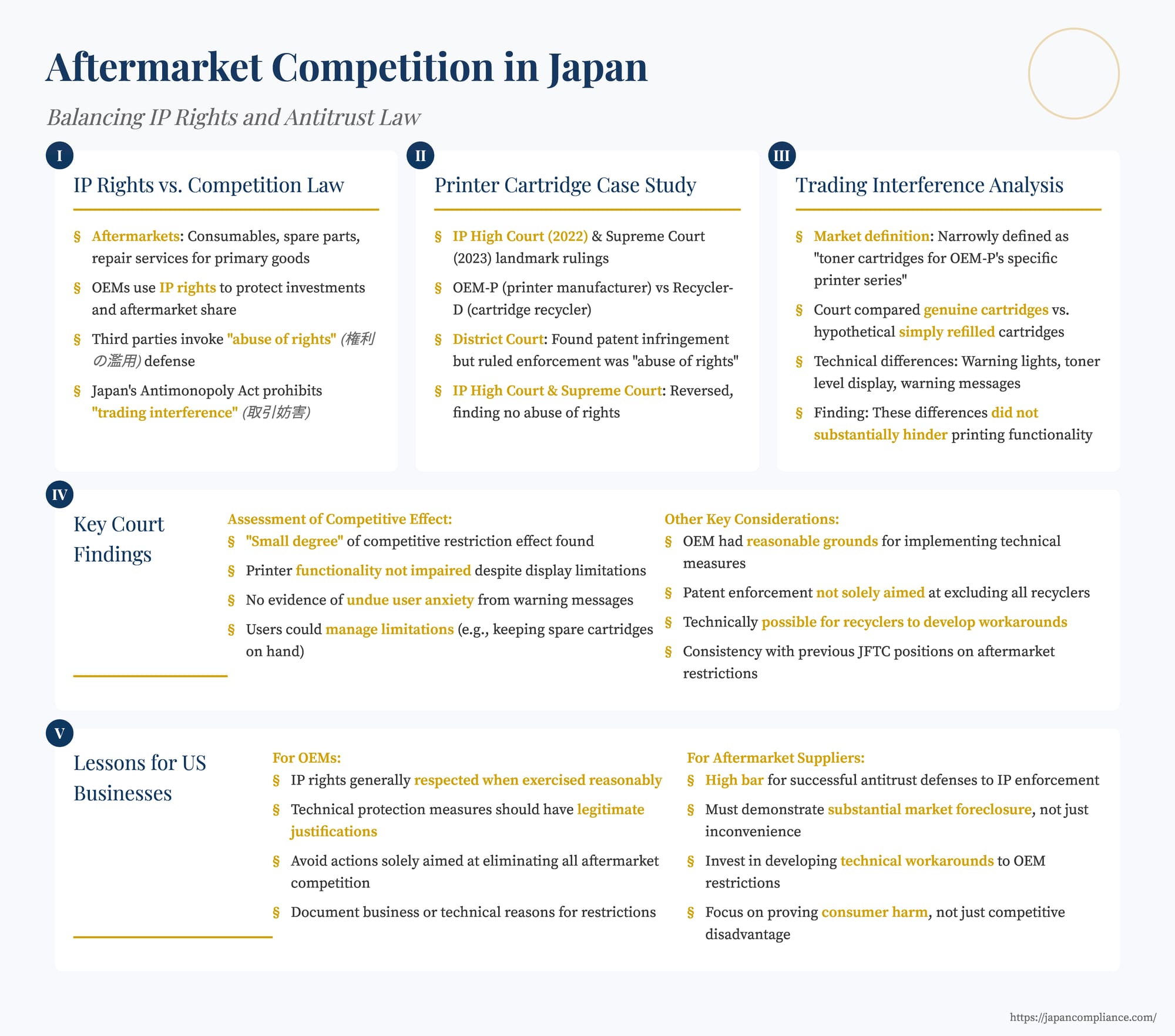

Japan’s IP High Court—upheld by the Supreme Court in 2023—ruled that enforcing toner‑cartridge patents did not amount to “trading interference” under the Antimonopoly Act. The judgment shows that Japanese courts require clear, substantial foreclosure of competition before overriding legitimate patent rights, offering practical guidance for OEMs and third‑party suppliers alike.

Table of Contents

- The Competitive Battleground: Aftermarkets and IP

- A Key Japanese Case Study: The Printer Cartridge Dispute

- Analyzing “Trading Interference” in the Aftermarket

- Outcome of the Case and Its Significance

- Lessons and Implications for US Businesses

- Conclusion: A Delicate Balance

The interplay between intellectual property (IP) rights and competition law is a critical area for businesses globally, and Japan is no exception. This is particularly true in "aftermarkets"—markets for complementary products (like consumables or spare parts) or services (like repair) that follow the sale of a primary durable good (often termed "foremarkets"). Original Equipment Manufacturers (OEMs) frequently use their IP rights to influence aftermarket competition, sometimes leading to clashes with third-party suppliers like recyclers, remanufacturers, or independent service organizations.

A significant 2022 decision by Japan's Intellectual Property (IP) High Court, subsequently upheld by the Supreme Court in 2023, offers valuable insights into how Japanese courts approach these tensions, particularly the defense that an OEM's patent enforcement constitutes an "abuse of rights" or "trading interference" under Japan's Antimonopoly Act (AMA). This case, concerning printer toner cartridges, provides important lessons for US businesses, whether they are OEMs protecting their innovations or third parties seeking to compete in Japanese aftermarkets.

The Competitive Battleground: Aftermarkets and IP

OEMs invest heavily in developing their primary products (e.g., printers, medical devices, automotive parts). The aftermarket for consumables (like printer cartridges, coffee pods) or repair parts and services can be highly profitable. To protect their market share and recoup R&D investments, OEMs often secure patents on these aftermarket products or components within them. They might also implement technical protection measures (TPMs) to make it harder for third parties to offer compatible alternatives.

Third-party aftermarket suppliers, on the other hand, argue that such practices can stifle competition, limit consumer choice, and lead to higher prices. When faced with IP infringement lawsuits from OEMs, these suppliers often raise defenses rooted in competition law, claiming that the OEM's actions are an abuse of their dominant market position or constitute unfair trade practices.

In Japan, such defenses might involve arguing that the IP holder's conduct is an "abuse of rights" (権利の濫用 - kenri no ranyou), a general principle under civil law, or that it violates specific provisions of the Antimonopoly Act, such as those prohibiting "trading interference" (取引妨害 - torihiki bougai), a type of unfair trade practice.

A Key Japanese Case Study: The Printer Cartridge Dispute

A pivotal case illustrating these dynamics involved a major manufacturer of printers and toner cartridges (referred to here as "OEM-P") and a company that recycled and refilled these cartridges (referred to as "Recycler-D").

Background:

OEM-P held patents on electronic components within its toner cartridges. These components stored data, for example, indicating when the toner was depleted. OEM-P had also implemented technical measures to restrict the rewriting of data on these genuine components. Recycler-D would acquire used OEM-P cartridges, replace OEM-P's patented electronic components with its own, and then refill and sell these cartridges.

OEM-P sued Recycler-D for patent infringement, arguing that Recycler-D's replacement electronic components infringed its patents.

The Lower Court's Decision (Tokyo District Court, July 22, 2020):

The District Court found that Recycler-D's components did indeed infringe OEM-P's patents. However, it dismissed OEM-P's claims, holding that the enforcement of its patent rights in this instance constituted an "abuse of rights." The court was concerned that OEM-P's actions were primarily aimed at excluding recyclers from the market rather than legitimately protecting its patented technology.

The IP High Court's Reversal (March 29, 2022):

OEM-P appealed to the IP High Court, which is a specialized high court in Japan with jurisdiction over IP matters. The IP High Court reversed the District Court's decision on the abuse of rights defense. While it agreed with the finding of patent infringement and also denied that OEM-P's patent rights had been exhausted, it concluded that OEM-P's actions did not amount to an abuse of rights.

A central part of the IP High Court's reasoning was its analysis of whether OEM-P's conduct constituted "trading interference," which is an unfair trade practice prohibited by Article 19 of the AMA (and further defined in General Designation No. 14 of Unfair Trade Practices, issued by the Japan Fair Trade Commission).

Analyzing "Trading Interference" in the Aftermarket

The IP High Court meticulously examined the elements required to establish trading interference of the "competition-reducing type."

1. Market Definition:

A crucial first step in most antitrust analyses is defining the relevant market. OEM-P had argued for a broad market definition encompassing the entire "business printer market" (including printers and their aftermarket). Recycler-D, conversely, argued either that no market definition was necessary for an "unfair means" type of interference, or, alternatively, for a very narrow market for toner cartridges for OEM-P's specific printer series, assuming user lock-in.

The IP High Court focused its analysis on the "market for toner cartridges for OEM-P's C830 series printers." This approach indicates a preference for defining markets based on the specific product and its closest substitutes, taking into account the practical realities of consumer demand in aftermarkets.

2. Assessing the Exclusionary Effect (Competitive Restriction):

The core of the "trading interference" analysis was whether OEM-P's actions (specifically, its technical measure restricting data rewriting on cartridge components and its subsequent patent enforcement) had a significant exclusionary effect on competitors like Recycler-D.

To assess this, the IP High Court compared two scenarios:

* (A) Users using OEM-P's genuine cartridges with the original electronic components and data rewrite restrictions.

* (B) A hypothetical scenario where users used OEM-P's cartridges that were simply refilled with toner by a recycler, without replacing the electronic component (this was not what Recycler-D actually did, but it served as a baseline for assessing the impact of OEM-P's technical measure).

The court identified several differences a user might experience with scenario (B) compared to (A):

* The printer's display might show the toner level as a question mark ("?").

* A yellow warning light might illuminate.

* A message like "non-genuine toner bottle is set" might appear.

* Detailed multi-level toner status displays would be unavailable; the display might just show "undetectable."

* There would be no advance warning when toner was low; the printer would simply stop printing when the toner was fully depleted, displaying an "out of toner" message.

Despite these differences, the IP High Court evaluated their impact on users and competition as follows:

* Printing Function Not Hindered: The court found that these display issues did not actually impair the printer's ability to print.

* No Undue User Anxiety: It was deemed unlikely that these messages would cause users significant anxiety about the printer's functionality.

* Manageable by Users/Recyclers: The court suggested that users could manage the lack of a precise toner level display by simply keeping a spare toner cartridge on hand. Furthermore, recyclers could proactively inform their customers that while printing quality is maintained, the display functions might differ from genuine cartridges.

Based on this evaluation, the IP High Court concluded that the "degree of competitive restriction effect was small." In other words, OEM-P's technical measures, while creating some differences in user experience, did not substantially foreclose competition from recyclers in a way that would constitute an illegal trading interference.

3. OEM-P's Justifications and Intent:

The court also considered OEM-P's rationale for its technical measures. It found that OEM-P had "reasonable grounds" for implementing the data rewrite restrictions on its cartridge components.

Furthermore, the IP High Court found that OEM-P's patent enforcement actions were not solely or primarily for the purpose of excluding all recycled products from the market. This finding on intent, while not always the sole determinant, often plays a role in abuse of rights analyses. If the primary purpose is seen as legitimate IP protection rather than mere market exclusion, an abuse of rights claim is harder to sustain.

4. Technical Feasibility of Workarounds:

A highly significant factor in the IP High Court's decision was the assessment that it was technically possible for recyclers to evade or work around OEM-P's data rewrite restriction measures. If recyclers could develop and implement their own compatible components (as Recycler-D did, albeit leading to the patent infringement claim) or find other ways to make refilled cartridges work effectively, it weakens the argument that the OEM's measures completely locked them out of the market. The ability for competitors to innovate around an OEM's technical protections is a key consideration.

5. Consistency with Prior JFTC Views:

The IP High Court's analysis also appeared to align with previous stances by the Japan Fair Trade Commission (JFTC). A JFTC press release from October 21, 2004, concerning another printer manufacturer, had suggested that actions which "deter users from using recycled goods" could be an indicator of an exclusionary effect. The IP High Court's finding that the user experience differences in this case were not sufficiently deterrent seems consistent with this line of thinking.

Outcome of the Case and Its Significance

Based on its finding that the competitive restriction effect was small, that OEM-P had reasonable grounds for its actions, and that its intent was not solely anti-competitive, the IP High Court concluded that OEM-P's patent enforcement did not constitute trading interference under the AMA and, therefore, was not an abuse of rights. OEM-P's claims for patent infringement were thus upheld.

Subsequently, Recycler-D appealed to the Supreme Court of Japan. In a decision in March 2023, the Supreme Court dismissed the appeal, effectively finalizing the IP High Court's ruling in favor of OEM-P.

Lessons and Implications for US Businesses

This case, culminating in the Supreme Court's affirmation, provides several important takeaways for US companies involved in Japanese aftermarkets:

- High Bar for Antitrust Defenses to IP Enforcement: The decision underscores that successfully defending against a patent infringement claim in Japan by arguing "abuse of rights" or "trading interference" under the AMA is challenging. Courts will require clear evidence of substantial anti-competitive effects. Merely making it more difficult or less convenient for third parties to compete may not be enough if the IP rights are valid and the exclusionary impact is deemed limited.

- Focus on Demonstrable Competitive Harm: For an antitrust claim to succeed, the alleged anti-competitive conduct must result in a significant, tangible restriction of competition in a well-defined market. Minor differences in product functionality or user experience, if they don't fundamentally prevent competition, may be insufficient.

- Technical Workarounds Weaken Foreclosure Claims: If aftermarket competitors have technically feasible means to design around an OEM's IP or technical protection measures (even if it involves cost and effort), it significantly undermines claims that the OEM has unlawfully foreclosed them from the market.

- OEM's Rationale and Intent are Relevant: While not the sole factor, the OEM's legitimate justifications for its IP strategy and technical measures (e.g., quality control, ensuring system integrity, protecting R&D investment) will be considered. If patent enforcement is perceived as a reasonable means to protect valid IP rights rather than a naked attempt to eliminate all competition, an abuse of rights claim is less likely to succeed.

- For OEMs: This case reinforces the general strength of patent rights in Japan when exercised within the bounds of fair competition. Implementing technical protection measures with clear, articulable, and legitimate business or technical justifications can be beneficial. However, actions perceived as solely aimed at stifling all aftermarket competition without such justifications could still face scrutiny.

- For Aftermarket Suppliers: The case highlights the need to present compelling evidence of significant market foreclosure and harm to consumer welfare. Simply being disadvantaged by an OEM's IP or technical measures is not enough. Demonstrating a lack of viable technical alternatives or clearly unreasonable, solely exclusionary OEM conduct would be crucial.

Broader Context:

It's important to remember that competition in aftermarkets remains an area of interest for antitrust authorities worldwide, including Japan's JFTC. The outcome of any given case will always depend on its specific facts, the nature of the IP involved, the conduct of the parties, and the actual impact on the market.

Conclusion: A Delicate Balance

The intersection of IP law and antitrust law in aftermarkets presents a delicate balancing act. OEMs have a legitimate interest in protecting their innovations and recouping investments, while competition authorities and courts seek to ensure that IP rights are not used to unreasonably stifle competition and harm consumer choice. This Japanese IP High Court decision, affirmed by the Supreme Court, offers a valuable window into how this balance may be struck in Japan. It suggests a rigorous approach to assessing claims of anti-competitive conduct, requiring clear proof of substantial harm before overriding legitimate IP rights. US businesses, whether acting as OEMs or aftermarket participants in the Japanese market, should carefully consider these principles in their IP and business strategies.